2018’s Most Crowded Trade

It started out as a whisper in early 2017, but by early 2018, it had reached a roar: “inflation is coming,” they yelled. After a decade mired in sub-par growth and near-zero interest rates, consensus agreed things were returning to normal. Portfolios repositioned, and rate-sensitive stocks repriced. But nearly six months later, the ‘whites in the eyes’ of inflation remain unseen. The German economist, Rudi Dornbusch once said; “the crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.” Could the same be said of inflation? Or will ‘lower for longer’ prevail? To find out, we asked three leading fixed income specialists, Charlie Jamieson from Jamieson Coote Bonds, Tamar Hamlyn from Ardea Investment Management, and Chris Rands from Nikko Asset Management.

What if consensus is wrong?

Inflation expectations are currently high across the world, but particularly in the US. Charlie Jamieson from JCB says the gap between inflation expectations and realised inflation is close to an all-time-high. Despite being close to the top of the business cycle, where you’d normally expect to see inflation appear, he says we’re not seeing the usual inflationary outcomes you’d expect at this point. In this short video, he examines what could happen from here.

Investors must consider the overall health

Tamar Hamlyn, Ardea Investment Management

To use a medical metaphor, higher rates and higher inflation should be viewed as symptoms of overall economic health, so it’s important to look more broadly at the patient when gauging the overall prognosis.

For this reason, high-frequency indicators of inflation such as oil prices are useful in their own right but might not capture the size or timing of a larger medium-term correction in rates or inflation.

Instead, it’s important to look at other aspects of the economy and markets that better capture overall health. Two of the best in our view are the US unemployment rate, and the term premium on long dated bonds.

US unemployment rates

US unemployment is a key driver for what is still one of the world’s largest economies in terms of both population and GDP. Unemployment rates, both short-term and long-term, are close to historical lows. This suggests the patient–the US economy–is in rude health, and well enough to withstand, and perhaps even demand, higher rates and higher inflation.

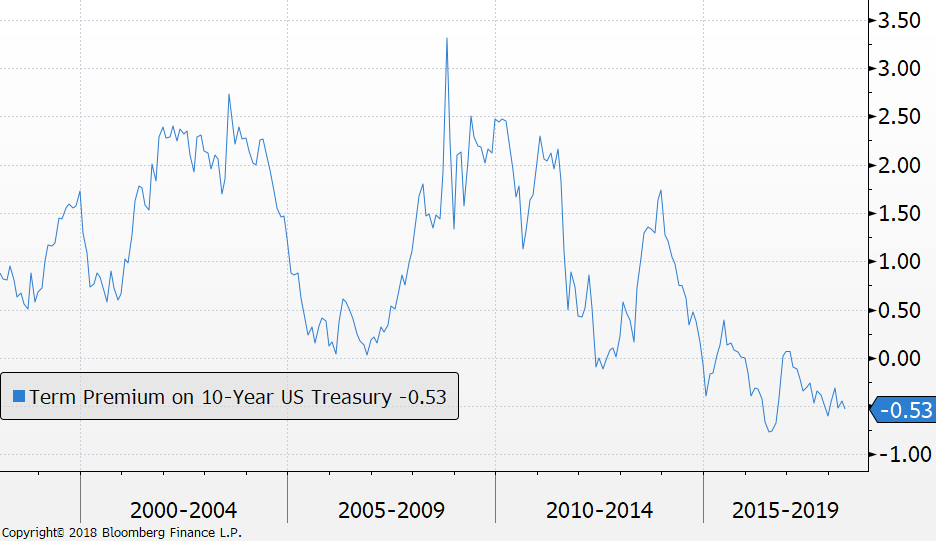

The term premium on long dated bonds tells a different story however. The term premium measures the additional compensation provided by bonds over and above the expected path of future cash rates. It’s at all-time lows, suggesting that compensation for investors is extremely slim.

Taken together, a strong economy should ultimately lead to better returns for investors, so investors should be positioning portfolios in ways that anticipate better rates of return in future.

Term Premium on US 10-Year Bonds

How can investors position for rising rates and rising inflation?

A rising term premium would demonstrate that the interest rates priced by financial markets were coming around to the idea that the patient, after all, is in fine health.

Positioning portfolios for such an environment is not entirely straightforward. While the cash flows of growth assets such as equities benefit from improving economic growth, at the same time their profits are reduced by higher financing costs as interest rates rise. Passive allocations to long-term bonds face the same challenge.

So, what can investors turn to? What is needed are differentiated sources of investment return that are not directly aligned to the major markets – that is, not aligned to either bonds or equities.

This means accessing non-traditional risk premia, which can be present in all asset classes. These might include opportunities that have gone under-utilised or under-exploited due to market inefficiencies, or opportunities to capture good value for providing liquidity to markets.

In fixed income, some of these opportunities can be found by positioning in volatility, the shape of yield curves and term premia, and in inflation-linked bonds and swaps.

So, while the trade in rates or inflation alone may be more crowded than last year, there are still plenty of opportunities to position for this risk.

But what if this is wrong?

The US economy is giving off every indication of strengthening economic fundamentals, consistent with higher rates and higher inflation over time.

But the future often differs from history, and there are some valid reasons why this might not come to pass.

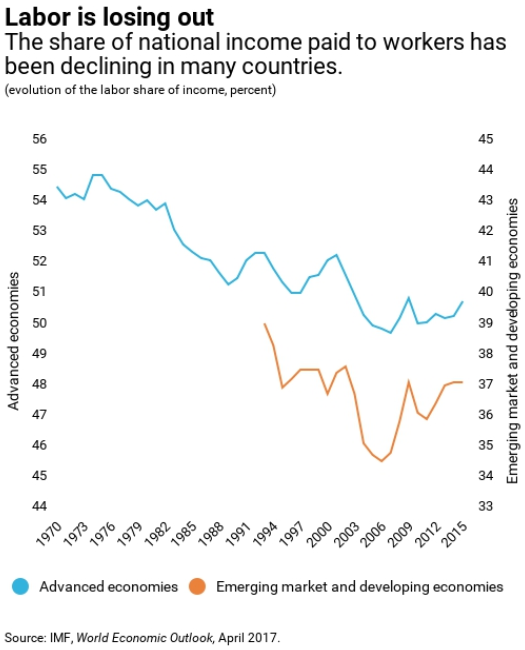

Much of the rising yields and rising inflation thesis relies heavily on a resetting of long-term structural trends around the breakdown of national income between labour (households) and capital (companies).

In many advanced economies, the share of national income captured by households is at all-time lows and has been for some time. The share of income captured by companies (not shown) is conversely at all-time highs.

With households under pressure on this measure, it’s perhaps no surprise that consumption – and by extension inflation – have been subdued. Similarly, with companies capturing a greater share of income, they are better able to finance their activities, and thus interest rates are lower all else equal.

So, the current low-rates, low-inflation dynamic is closely aligned with the current breakdown of national income between households and companies.

Are these long-term structural aspects likely to change any time soon? The ever-lengthening list of knowledge-economy challenges suggests: perhaps not.

These challenges are well-known and include demographics, technological change, and widening income inequality and its impact on total consumption.

The potential downstream effects of these developments are not yet fully appreciated, and they could well perpetuate the current swing in national income towards companies and away from households.

If the scenario of higher rates and higher inflation doesn’t come to pass, it will most likely because these knowledge-economy developments were able to prolong the current status quo for longer than anticipated.

However, even in such an environment, non-traditional risk premia are likely to remain accessible to investors. These opportunities to increase returns will become increasingly sought out if conventional sources of return such as yield or capital growth remain subdued.

Chinese economy drives domestic inflation

Chris Rands, Nikko Asset Management

Australian inflation improved slightly over 2016/2017 as the Chinese economy showed stronger than expected growth. Over this period exports from Australia to China rose from -20% to +80%YOY, taking national income, corporate profits and inflation higher.

Source: Bloomberg

When breaking down inflation by domestic (non-tradeable) and international (tradeable) components, a nuanced picture emerges. On the domestic front, inflation has already shown a strong improvement — rising from 1.6% to 3.1% — as commodity prices improved. This reflects the stronger performance of the Chinese economy.

Source: Bloomberg

The AUD ain’t what she used to be

Looking forward, the strength of China will continue to be pivotal for domestic inflation. The risk at the moment is that monetary growth (M1) in China has started declining, which lead the strength of their economy by six months, implying some slowdown could occur.

Source: Bloomberg

The reason Australian inflation has struggled to get above 2% over the past two years is that international (tradeable) inflation has been extremely low. Typically, a falling AUD would take this inflation higher, however since 2010 this relationship has broken down meaning the lower Australian dollar hasn’t helped like it used to. There are a few theories of why this is occurring, but the bottom line is that until the international component improves inflation will be lower than expected.

Source: Bloomberg

What these indicators highlight is that part of the inflationary pulse in 2017 was about a stronger China, which may soon dissipate. If that were to occur, the RBA will need to hold cash rates stable for even longer than they expect, which would be positive for short-term bond yields.

3 topics

2 contributors mentioned