Short term outlook no roadblock for optimism

A lot has happened over the last quarter, with equity markets enjoying a very sharp rebound. Most economies have begun to reopen and many people’s lives are beginning to return to a ‘new normal’, but a lot also remains the same. Debate continues to focus on what the likely impacts of the coordinated fiscal and monetary stimulus measures will be; whether this stimulus, combined with the emergence of spare capacity following economic contractions, will be inflationary or deflationary; and, in this uncertain world, should portfolios be tilted towards cyclically-exposed companies or towards those with more defensive earnings streams?

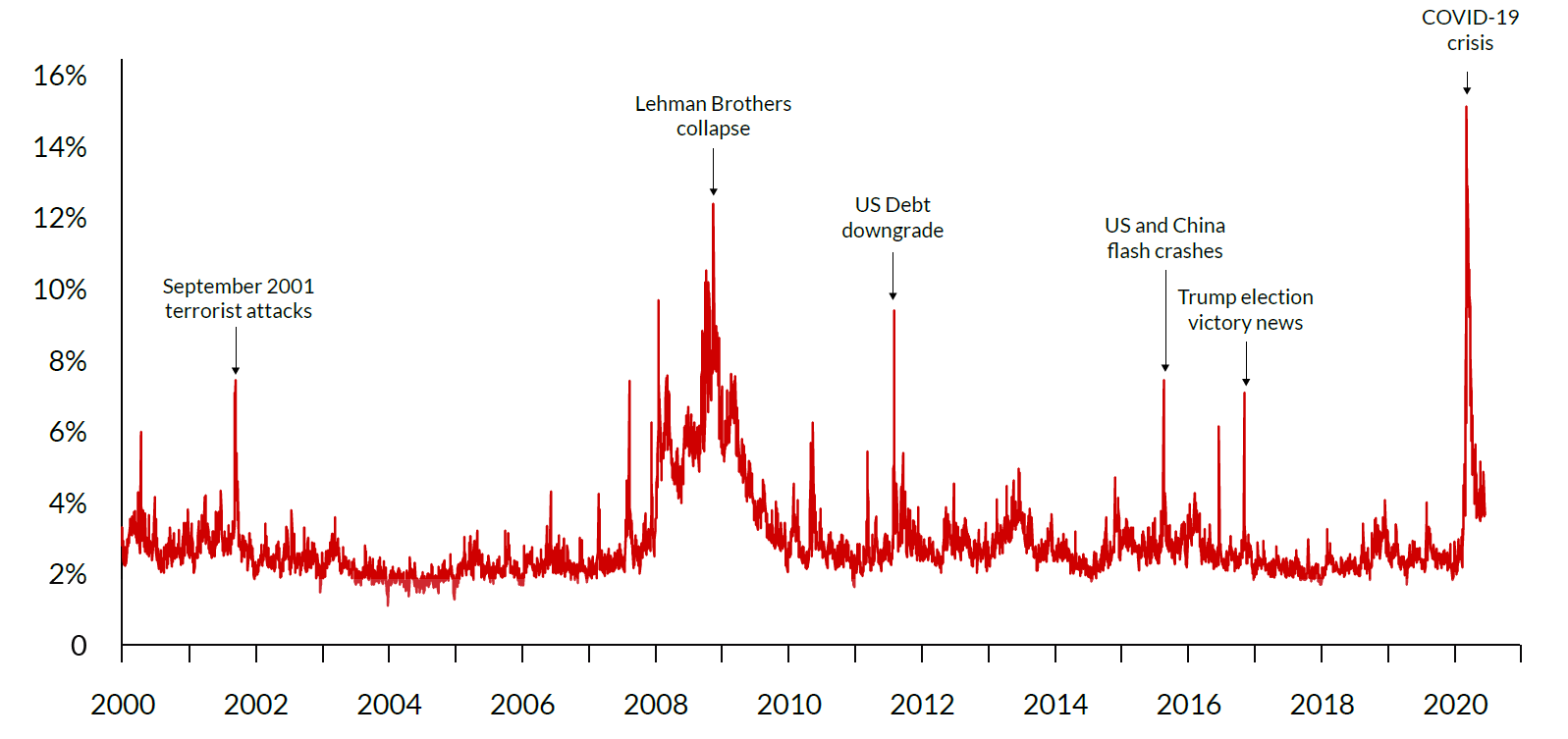

Volatility seems to be a product of this elevated uncertainty. To illustrate the extent of the current volatility we have used a simple measure of intraday price fluctuations. For each of the S&P/ASX 200 Index constituents, we have taken the difference between that company’s daily share price high and its daily share price low and divided it by its opening price. Using a simple average across all 200 companies gives a measure of the broader market’s intraday volatility. In Graph 1, which shows intraday volatility for the past 20 years, it is clear that the spike in volatility that we experienced in March dwarfed all other periods of volatility. And volatility in June remained elevated relative to the average of the past 20 years.

Graph 1: Intraday volatility of the S&P/ASX 200 Index since 1 January 2000

Source: Allan Gray Australia, JP Morgan, 22 June 2020.

It is rare for a company’s intrinsic value to fluctuate much from day to day. This daily volatility is not the result of rapidly changing economic forecasts or new structural changes that impact the average company’s future and value. Instead, it is more likely to be the result of non-fundamental factors that flow from elevated levels of uncertainty. Forced or panic selling during periods of reduced liquidity probably accounts for some of the volatility, but the changing emotions of the herd investors probably explains a lot too.

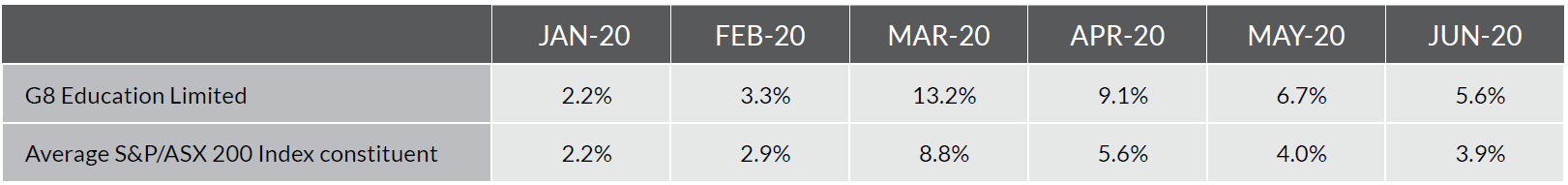

Instead of us adding to the myriad of market commentary that exists with our own opaque crystal ball, we thought it would be best to give an example of what we’ve been doing in the midst of this market volatility. G8 Education Limited (G8) has been twice as volatile as the average S&P/ASX 200 constituent (refer to Table 1) and now represents approximately 1.5% of the Equity portfolio, up from February’s pre-COVID-19 weight of less than 0.5%. Surprisingly, volatility remains elevated (compared to the average company), despite the Government support packages announced and its significantly reduced financial leverage following an equity raising.

Table 1: Monthly average intraday volatility in 2020

Source: Iress, JP Morgan.

We have progressively built our position throughout the year and investment analyst Justin Koonin discusses our investment thesis below.

G8 Education Limited – company background

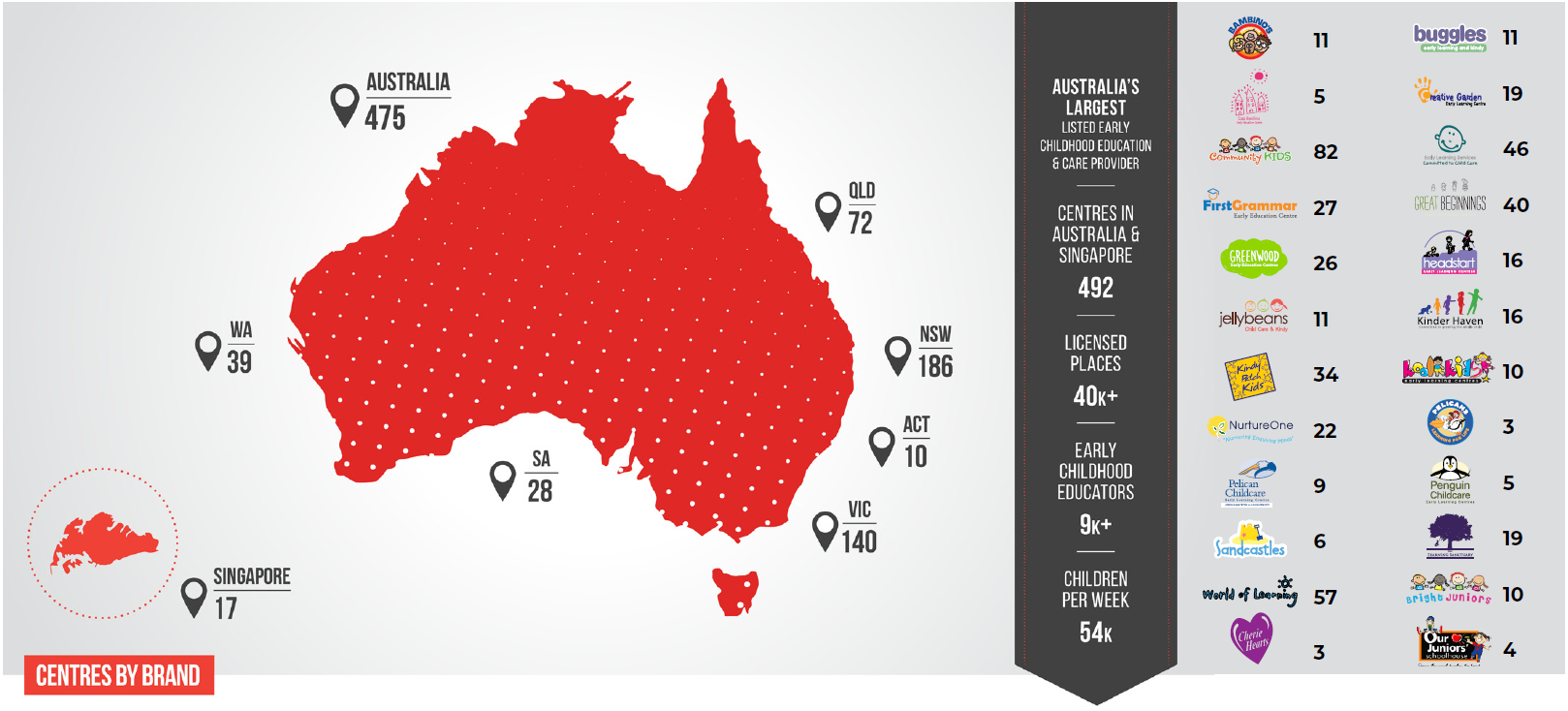

G8 Education Limited (ASX: GEM) is Australia’s largest publicly listed operator of childcare centres. It operates 492 centres in Australia and Singapore.

The company listed in December 2007 as Early Learning Services (ELY), operating five centres, with ambitious acquisition plans. In early 2010, ELY merged with Payce Child Care (PCC), and became G8. At this stage, ELY operated 38 centres, and PCC 60.

Since that time, the company has been a voracious roll-up company, acquiring and merging with other childcare companies, and operated 24 brands at its peak. When current management took over in 2017 there were 19 brands, and there are plans to reduce this further over time. Figure 1 shows G8’s childcare centres by geographic region as well as brand.

Figure 1: G8’s childcare centre brands and geographical split

Source: G8 Education.

G8 does not own its centres, but rather rents them from a landlord. Under normal circumstances, childcare operators make money by charging a daily rate (typically about $100 per child on average across Australia) to attend. Fees are subsidised by the federal government Child Care Subsidy (CCS), which operates on a sliding scale depending on combined parental annual income, the type of service (e.g. long day care, preschool, family day care), and the number of hours parents are working or studying.

Why has G8’s share price fallen so sharply?

G8’s share price fell from over $5 per share during its roll-up heyday in 2014 to a low of $0.44 in March 2020, though at the time of writing it had almost recovered to $0.90. This dramatic fall was principally due to three key factors:

- Like many roll-ups, poor capital allocation in its pursuit to grow saw the founders and previous management team significantly overpay for new childcare centres. This was justified by projected future income that has proven to be wildly optimistic.

- In recent years there has been an oversupply of childcare centres, fuelled by opportunistic developers, speculation and cheap credit. With this oversupply has come reduced occupancy across the system and, given the fixed cost bases of these businesses, significantly reduced profitability.

- More recently, COVID-19 created the perfect storm. With the country moving towards lockdown, parents began pulling their children out of childcare and the market began to have existential fears for the childcare sector.

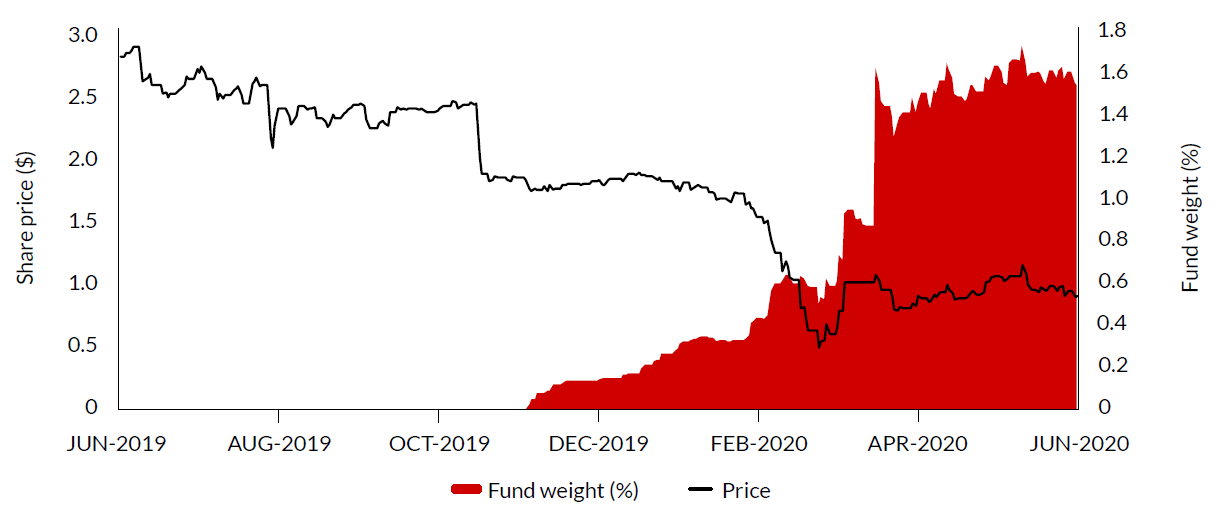

There is reason to be optimistic about the future though. The current management team and Board appear to be significantly more sensible in their allocation of capital than the previous management team and Board were. Also, the passage of time and a tightening of bank lending criteria have slowed new supply. Lastly, it is quite possible that the worst of the COVID-19 lockdown is behind us with occupancy levels beginning to improve – more about this below. These, combined with the significantly lower share price, have seen the Allan Gray Australia Equity Strategy portfolios accumulate a stake in G8 with our first purchases in December 2019.

Graph 2: G8 share price relative to the share’s weighting in the Allan Gray Australia Equity Fund

Source: Allan Gray Australia, Datastream. The Allan Gray Australia Equity Fund is representative of the Allan Gray Australia Equity Strategy and institutional mandates that share the same investment strategy.

Childcare in a COVID-19 world

In a world with high fixed costs and, during a potentially extended lockdown period, very few children in care, it is understandable why the market thought childcare centres may not survive, at least in the absence of government intervention. But it is also difficult to see how the government would allow a sector that plays a critical role in national productivity to collapse. Sure enough, in early April the federal government announced a support package for the sector. Childcare centres which remained open (and 99% did) would receive 50% of their pre-COVID-19 revenue, regardless of how many children attended. Parents would be offered free childcare during the pandemic. By design this, together with a pandemic-related government programme to subsidise wage costs (the JobKeeper programme), meant that G8 would break even while these arrangements remained in place.

As a result of increasing demand as the lockdown has eased, the government has announced transitional arrangements before the sector returns to its old funding formulas from September, when the economics of the sector will revert to being driven by three key factors: occupancy, revenue per place and operating costs.

What is the market pricing in?

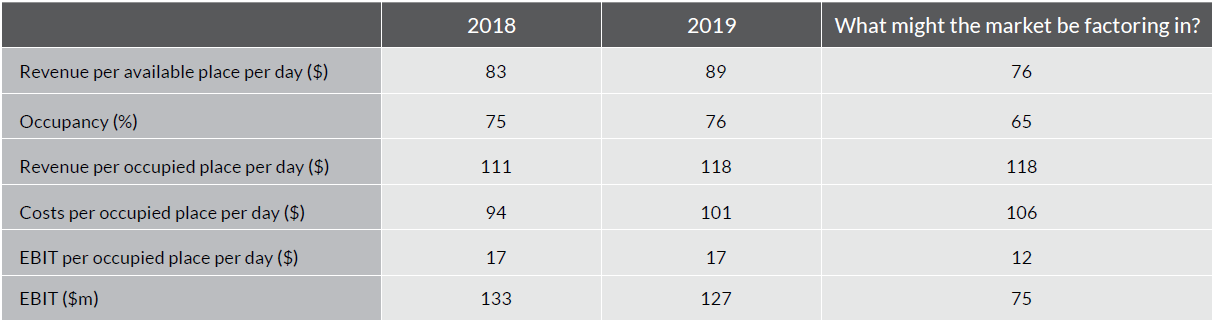

Average operating earnings for the company have been $146m p.a. since 2015, the first full year at which it operated at current scale. Earnings in 2019 were a little lower than this, at $127m, principally due to the previously mentioned oversupply issues and resulting occupancy headwinds.

The company has previously guided to a potential $45m uplift in operating earnings, due to a ramp up of its greenfield developments and a turnaround in underperforming assets. Our thesis does not rely on this and we ignore its potentially positive impact below.

Earnings are particularly sensitive to centre occupancy levels, given large fixed costs. For G8, these have fallen from 84% in 2014 to 76% in 2019 (pre-COVID-19), largely due to the surge in supply.

To be more precise, it appears that each percentage point change in occupancy levels creates roughly a $4m change in operating earnings – at least when occupancy is near pre-COVID-19 levels. As occupancy decreases this sensitivity increases and the company is likely at break-even point when occupancy is in the high-50s (%).

The current market capitalisation of G8 is around $740m, and with net debt (post a somewhat surprising capital raising in April) of about $65m, the total enterprise value of the company is about $805m. This represents a pre-tax multiple of less than 6.5 times 2019’s levels or about nine times post-tax earnings. This is significantly cheaper than the broader sharemarket and seems to factor in an expectation of occupancy levels well below 2019’s 76% and mostly likely something closer to 65%. Current centre bookings are already at these levels, although parents are not currently paying for childcare so perhaps this level won’t be sustained in the near term.

Table 2: G8’s childcare centre unit economics

Source: Allan Gray Australia, G8 company financial statements (AASB16 adjusted).

What could go wrong?

The biggest issue to our investment thesis concerns the performance of the company in the midst of a significant economic recession. This is somewhat unknown but potentially problematic. Rising unemployment means that parents have less disposable income to spend on childcare, as well as more time to take care of their children. Under this scenario, occupancy could fall significantly and 2019 comparisons would prove optimistic.

Two things are worth noting in this respect: firstly, it is important to remember what occupancy levels are implicit in G8’s share price today. At close to 65% (refer to Table 2), this is 11 percentage points below pre-COVID-19 levels. Sustained falls to these occupancy levels would be representative of a very weak economy with persistently high unemployment levels. Many other childcare operators would be in even more pain if G8 were at these levels of occupancy.

Secondly, under a scenario in which G8’s occupancy falls to 65% or below, it is unlikely that childcare would be the only part of corporate Australia that would experience profitability headwinds. Flow-on impacts could be expected in sectors that trade at far richer multiples today. As a result, were this scenario to unfold, G8 may still perform significantly better than the average company.

It is clear that there are storm clouds ahead as JobKeeper ends and parents are forced once more to pay for childcare. But investing is a game of probabilities and we often find our best opportunities when the near-term outlook appears dire. The market appears to be pricing in much lower and sustained levels of occupancy and levels of occupancy that would threaten the viability of a number of operators. That seems an unlikely longterm outcome and so, despite this period of heightened volatility, we think we have found a company in G8 that offers the portfolios something we continuously search for: an asymmetric set of payoffs in the long run.

The above wire is an extract from our quarterly report, which you can find in full here.

Want to learn more?

Contrarian investing is not for everyone, however there can be rewards for the patient investor who embraces Allan Gray’s approach. To stay up to date with our latest thinking, hit the follow button below or contact us for further information.

2 topics

1 stock mentioned

1 contributor mentioned