2021 Credit Outlook

FIIG Securities

The health crisis that combined elements of the Spanish flu pandemic, the Great Depression and the GFC helped redefine what fiscal and monetary policies can achieve. The year ahead will tell us the willingness of central banks and governments to maintain the course – we think they will.

Review of 2020 – where should we start?

What the last year has taught us is that we are in an environment where the words “traditionally” or “typically” have had to be discarded given the unprecedented nature of the events we are continuing to experience. Many have used the Spanish flu pandemic in the late 1910’s or the Great Depression of the 1930’s as points of comparison but we have to accept we are now in a very different world, with global economies and financial markets simply experiencing events that have never been seen or even considered before.

So, why is the COVID-19 pandemic such a one-off event? From a health perspective, many comparisons can be drawn from the Spanish flu pandemic. The impact on economies has some similarities with the Great Depression. And yet, two major factors undeniably make the current pandemic a once-in-a-lifetime event (or at least we sincerely hope). The first of these factors is that we now live in a widely interconnected world where you can go from one point on the globe to its exact opposite point in less than 24 hours, making the containment of a disease virtually impossible without drastic measures constraining people’s freedom of movement. The second is that the tool box to fight the impact of such a crisis is a lot more diversified.

Australia’s response to the pandemic probably best illustrates these two factors:

- As cases started to rise (mainly overseas rather than domestically), Australia introduced border controls from early February, followed in mid-March by much tighter restrictions which led to the first lockdown.

- The second factor was the ability and willingness of governments and central banks to take a ‘whatever’s necessary’ approach to combat the impact of the restrictions imposed.

Performance of credit and financial markets during 2020

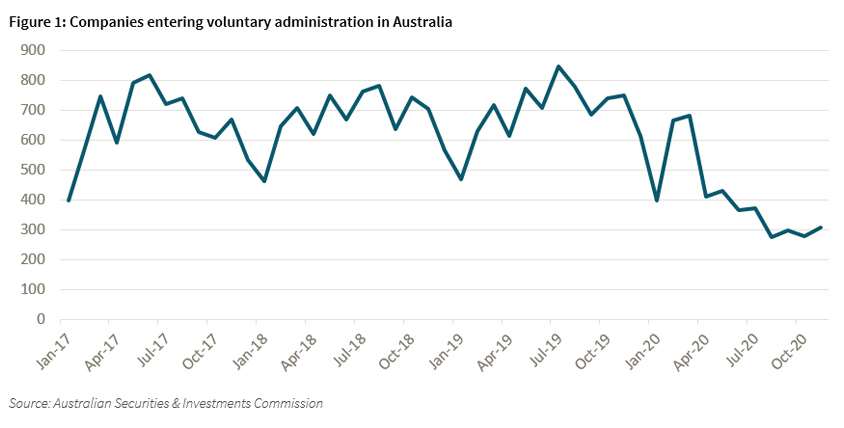

A shock of the magnitude we experienced in 2020, even with many government support measures, will always result in a deterioration of the credit quality of many companies. The extent of this deterioration has again varied between countries as a result of measures implemented and, to an extent, mechanisms in place for companies to operate while under financial stress (e.g. Chapter 11 in the US or the voluntary administration process in Australia).

In Australia, in light of the likely rise in insolvencies, the government introduced measures to provide temporary relief and not force companies into bankruptcy with the likely loss of many jobs.

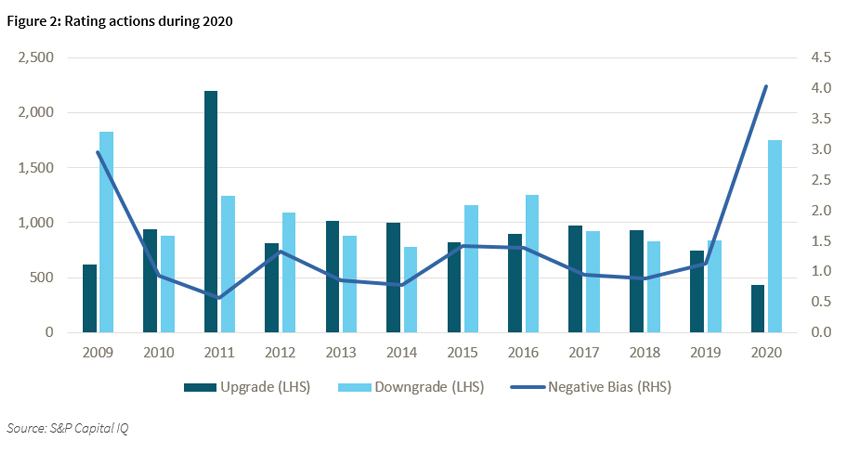

Looking at the impact on credit quality that COVID has had on businesses solely through the lens of insolvency filings is perhaps somewhat misleading. Another way to assess credit quality is to observe the number of rating actions over the period.

While ratings will generally provide an indication of creditworthiness for larger companies (as credit ratings are generally prohibitive for smaller companies from a cost perspective), they provide a more granular picture of how the universe of rated companies has evolved during the last 12 months.

When we look at what sectors were most affected by downgrades, it will come as no surprise to see that consumer discretionary and energy companies are leading the pack. At the other end of the spectrum, utilities and financials had the lowest number of downgrades (as a percentage of the total number of entities). This again should come as no surprise given utilities are ultimately supporting services and products that are essential and financials received the benefit of very favourable monetary policies during the year.

What about 2021?

Looking at the year ahead requires at best a very good crystal ball (which we don’t have). What will happen with the virus? Will the vaccine be successful? Is the situation going to materially deteriorate in Europe and the US? What are governments going to do if things get better or worse?

At this stage, forecasting how global economies are going to perform is almost impossible. You will hear many commentators attempting to do it but with enough assumptions around the containment of the virus that a forecast really becomes a scenario analysis rather than a view of future performance.

In our view, it is more prudent to consider near term economic performance in the context of fiscal and monetary policies. As 2020 has clearly demonstrated, governments and central banks are willing and able to influence their policies to achieve a desired outcome. As such, it is more relevant to think about what these institutions will be aiming to achieve and assuming that they will adjust their stance based on how the pandemic evolves. In our view, we believe that the aim will be to maintain broad financial stability and start to recover economically from the impact of the virus. What does this mean?

Simplistically, maintaining financial stability will be achieved if credit continues to flow through the economy, ensuring that individuals and companies can still borrow and spend, all of this at a reasonable cost. It also means that financial markets confidence continues to improve (although some would argue that markets are already overly optimistic, especially from an equity valuation perspective). This will fall under the responsibility of central banks.

Economic recovery will be a function of seeing every part of the economy fully reopening, which should drive economic growth and see unemployment start to trend down. Governments and their fiscal policies will play the key role.

Interestingly, both governments and central banks are likely to face the same challenge, i.e. how to handle market expectations. The consequence of not meeting expectations is quite different between the two groups. For governments, it is about voters’ expectations and, like it or not, many politicians will be driven by how their decisions will impact their chances at any upcoming elections. Will fiscally responsible budgets win the day even if it is to the detriment of a large portion of voters who would be better off with direct government support? Central banks on the other hand do not have the voters’ pressure which could arguably give them a chance to play the longer game but they are facing financial markets which will react a lot faster than voters if their expectations are not met. These dynamics probably make predicting the behaviour of central banks easier than the behaviour of governments. This is because central banks are nowadays heavily relying on forward guidance which provides sufficient indication as to what each one is trying to achieve. The dynamics on the fiscal policy front are a little bit more complicated to predict. For example, the Australian government sent a very strong signal at the start of the pandemic that it was willing to do whatever was necessary, with JobKeeper and JobSeeker being probably the two best examples. Since then, the government has attempted to gradually wind back those measures but has clearly shown signs of being torn between fiscally responsible policies and not creating a shock to the economy. Turning down, rather than turning off support measures has so far been successful but the longer term effects remain unknown, especially considering the last COVID-19 outbreaks in certain parts of the country.

Interestingly, a major impediment to a stronger recovery in Australia which might force the federal government to continue with support measures is the continued travel restrictions around the country and yet these are controlled by states rather than centrally.

While Australia has so far shied away from putting all its eggs in the vaccine basket (and instead pursuing an elimination strategy), the continued discrepancy between state policies around domestic movements might force the federal government’s hands into fast-tracking the vaccine rollout.

What does this mean for financial markets?

As explained above, focusing on economic growth and trying to forecast the increase in GDP is not so relevant if we assume governments will implement fiscal policies to deliver this. In our view, this year will be about setting a trajectory which will deliver a fall in unemployment (although it is not likely to be material until the back end of 2021 at the earliest) and a sense of return to normality. This approach may appear controversial, but let’s remember that, unlike previous economic downturns, this one was the result of a health pandemic rather than a typical end-of-economic cycle recession. If successful, this should result in a strong(er) economy which will allow many companies to recover from the deterioration in credit quality experienced in the past 12 months. There is no doubt that some will not survive the unwinding of economic support measures they have benefited from but one could argue that the vast majority who weren’t going to make it have either fallen over or are on the verge of doing so.

Where there is an expectation that default rates will go down (given the spike experienced in 2020), this should not be construed as an overall improvement in credit quality across the board. In fact, markets are expecting a moderate deterioration across the rating spectrum during 2021.

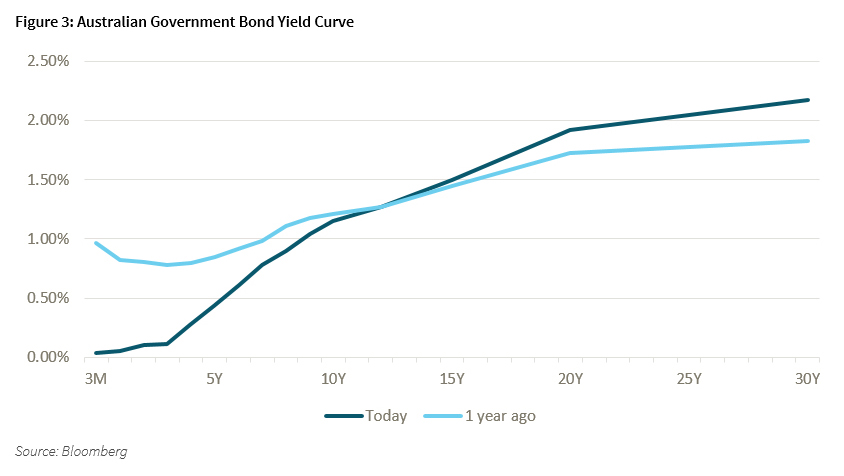

Government bond yields are, on the other hand, expected to rise, although it will be more pronounced at the longer end of the curve given the expectation that central banks will continue to actively manage the shorter end of the curve (i.e. maturities of three years or less) at historically low levels (as witnessed by the RBA and its target 3-year yield of 0.10%, which we see no reason for changing in the near term).

Implications for a fixed income portfolio

Conventional wisdom has in the past dictated that, in the event of an expected rise in interest rates, the broad strategy for a fixed income portfolio was to favour floating rate over fixed rate and shorter rather than longer maturity. This was to avoid positions whereby long dated low coupons were fixed and would then experience a fall in capital price (recall that, as yields rise, capital prices drop). But, if 2020 has taught us anything, long held conventional wisdom is probably no longer relevant when faced with unprecedented events and both governments and central banks are willing to go to great lengths to lessen the impact, even by implementing measures not seen before.

While it is undeniable that the consensus is for interest rates to go up (which will negatively impact capital prices), it is important to also put this in the context of the yield curve and in particular the difference in yield between one maturity and the next. At the moment central banks are controlling the shorter end of the curve, while the longer end (10 years and more) is left to be determined by market dynamics. Central banks, through bond purchasing, will also intervene in the middle of that range. As optimism recovers and long government bond yields will rise, this will likely result in a steepening of the yield curve, i.e. the incremental yield from one maturity to the next will get larger.

We believe that current market conditions (and what we expect over the next 12 months) will also continue to offer opportunities where the price of certain securities doesn’t necessarily reflect fundamentals or where the expected spread compression could have a comparatively greater impact.

For example, we see some value in considering opportunities further down the capital structure for issuers that are otherwise exhibiting strong credit fundamentals (such as bank or corporate hybrids). We also see continued value in residential mortgage backed securities, given the positive outlook on property, strong historical performance in the sector and the fact that many investors continue to shy away from that asset class (enabling the delivery of stronger yields at equivalent ratings, noting that these higher spreads also reflect the fact the securities are not as liquid as corporate bonds).

Inflation linked securities, which we believe have a place in any portfolio, are currently somewhat challenged by the relatively weak inflation outlook (when considering it against the RBA’s target range), with many yielding in real terms (i.e. before inflation adjustment) less than 1%, and some in negative territory. Given the near term inflation outlook, our preference remains for longer dated instruments, especially as the ongoing maturity of existing instruments and lack of new supply should positively benefit the capital price of these instruments due to their growing scarcity.

Finally, as many investors seek income (as well as capital appreciation) from their fixed income portfolio, an appropriate and well diversified allocation to high yield securities continues to be appropriate although we continue to believe that the exposure to any single issuer should be commensurate with the inherently higher risk compared to investment grade securities.

Ultimately, and more than ever given the uncertainty that will no doubt continue over the coming months, being selective and maintaining a high degree of diversification (across maturity, issuer, rating, currency and instrument type) continues to be the key to a well-balanced fixed income portfolio. More generally, we continue to believe that an allocation to fixed income remains more important than ever. While equities performance has been stellar in recent months, the current valuation of equities simplistically assumes interest rates will remain at current levels forever. Hard to possibly believe this. The price-to-earnings ratio for the S&P500 index in the US is now higher than immediately prior to the tech bubble of 2000. What followed was a crash of the index by more than 30% in the following 9 months and it took another 7 years to fully recover. Many commentators had argued that the equity market was ready for a correction last year. COVID-19 has introduced many fiscal and monetary policies that have avoided this outcome but it is likely that the correction will eventually occur. The question on everyone’s mind is when. Many indicators would point to sooner rather than later, although probably not until there is a return to some form of normality.

4 topics

Thomas joined FIIG Securities in March 2018 and heads the Research team. Thomas has over 15 years’ experience in credit and fixed income markets across Europe, Asia and Australia.

Expertise

Thomas joined FIIG Securities in March 2018 and heads the Research team. Thomas has over 15 years’ experience in credit and fixed income markets across Europe, Asia and Australia.