2024: The year of clear waters and abating uncertainty

The turning point is in! We finally believe that Australian official interest rates have peaked, and inflation appears to be in retreat, with the economy slowing sufficiently on a per capita basis to take the heat out of price rises.

As we enter 2024, we see much of the uncertainty ending and a period of getting used to the ‘new normal’ beginning. Prices are higher, the population is higher, economic growth is lower (but for now we don’t see this becoming negative), unemployment is lower, interest rates are higher.

Markets traditionally dislike uncertainty and in 2024 uncertainty is expected to abate, creating many opportunities. Household consumption is set to rise, and as continued steady wage growth meets easing inflation, real wages should rise too.

Australian residential property prices (a key focus of ours) are forecast to lift slowly and steadily in 2024 as the market digests the full impact of the last few years. Our larger population needs somewhere to live and there are too few vacant properties, and equally too few new to market properties to soak up this demand. Builders who have weathered the perfect storm of the last few years will enjoy the backlog of projects ready to launch and we feel, enjoy solid margins, returning much needed profitability and stability to the sector.

What have we seen?

The RBA is under new stewardship, but Governor Michelle Bullock has proven steadfast in confirming their commitment to using interest rates as a lever against inflation. Another rate hike at the November 2023 meeting brought the official interest rate to their highest level since 2011 at 4.35%

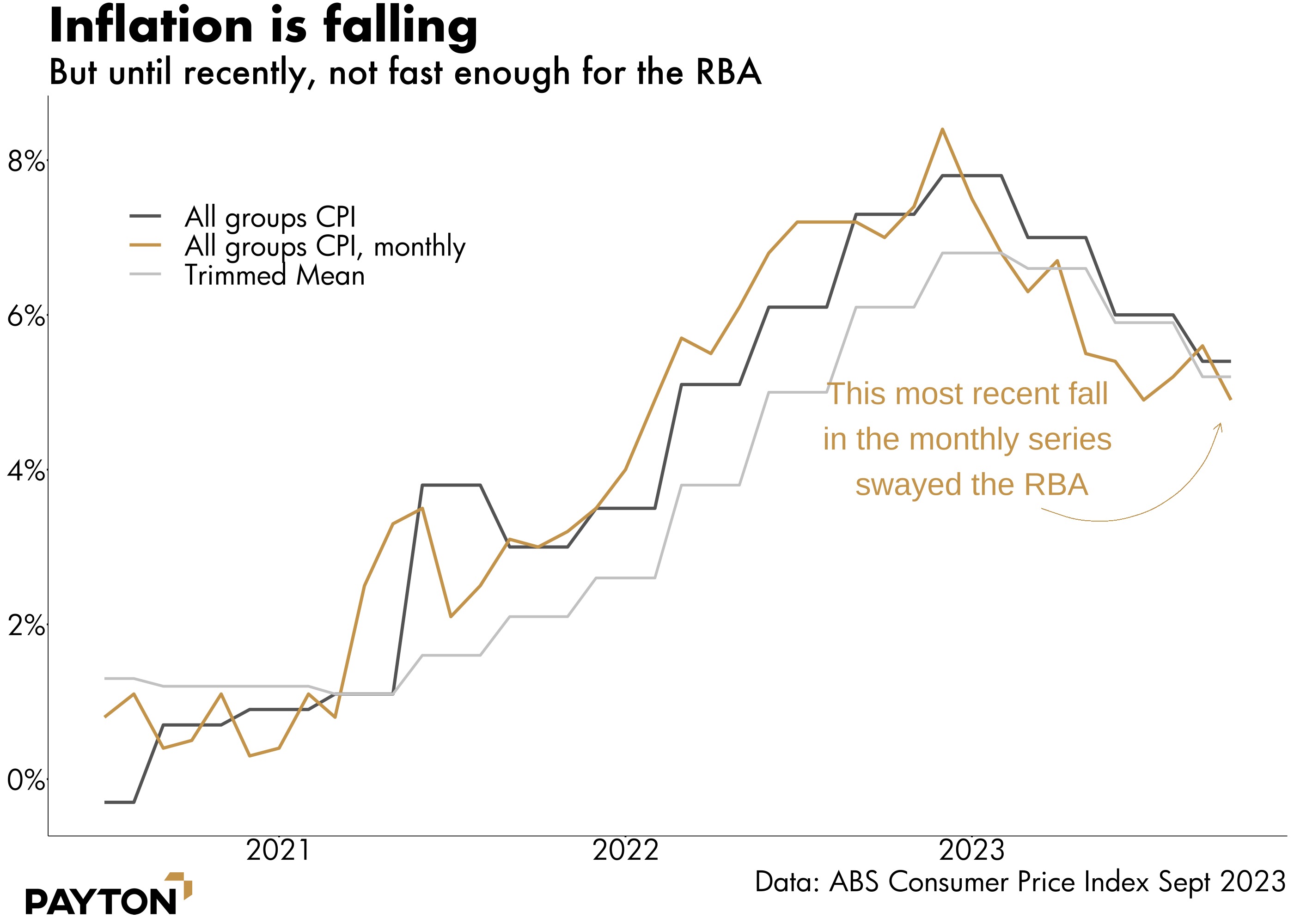

That increase in rates followed an uptick in the monthly CPI indicator. The statistics bureau now produces inflation data monthly instead of four times a year and the RBA understandably was rather sensitive to the most recent monthly figure. The monthly indicator rose to 5.2 per cent in August rather than falling, and then rose again to 5.6 per cent in the September data, which came out just prior to the November RBA meeting. That was no doubt a key trigger for the RBA to raise and justify the raise in the face of a cost-of-living crisis.

They hiked, saying “the risk of not achieving the Board’s inflation target by the end of 2025 had increased.” But after the meeting came a reversal – the next monthly data point, for October, was far lower, as the next chart shows. Annual inflation returned to 4.9 per cent.

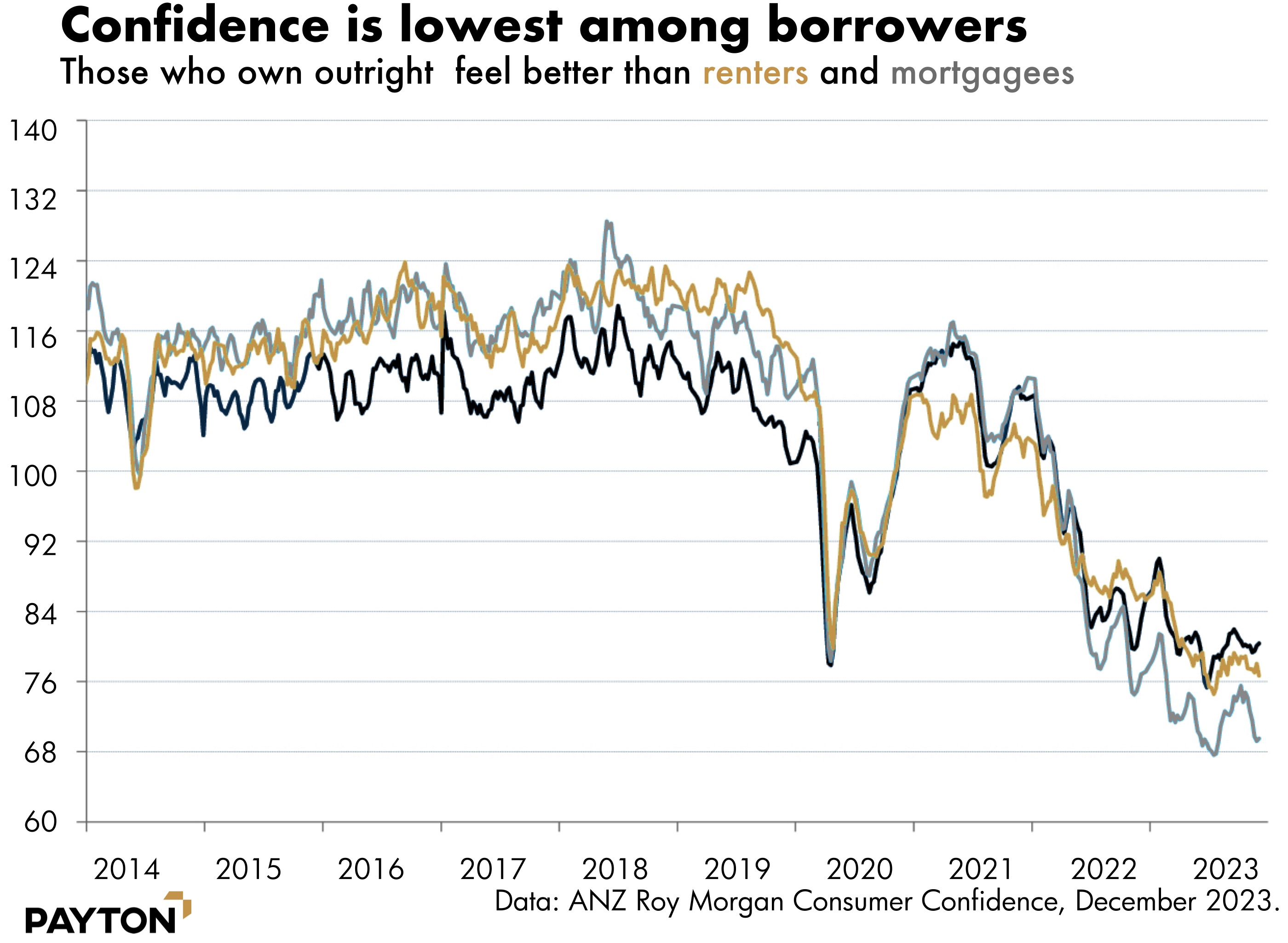

The continued rate rises have been painful for some households. Subjective perceptions of the state of the economy are divergent, and whether a household has a mortgage or not is the key to understanding those perceptions.

As the next chart shows, households with mortgages have generally been optimistic during the history of Australia’s consumer confidence data. That data stretches back to 2014, i.e. covering a period when interest rates were usually falling.

Now, however, rates are rising, and it is those who own their own home who are demonstrating a greater confidence in the economy as interest rates on their deposits rise with each RBA movement.

Cash in the bank

The problem the RBA faces is this: rate hikes do little to deter spending by households without debt. Indeed, the amount Australians have in bank deposits is at historically high levels, and those are earning good interest. A term deposit can generate over 5 per cent right now, which is the highest nominal interest rate in many years. Even accounting for inflation of 4.9 per cent, it is a positive return.

Saving households and borrowing households are both living in the same economy but experiencing it very differently. There is a dichotomy: higher rates are causing many households to tighten their belts, but a smaller group is enjoying a windfall.

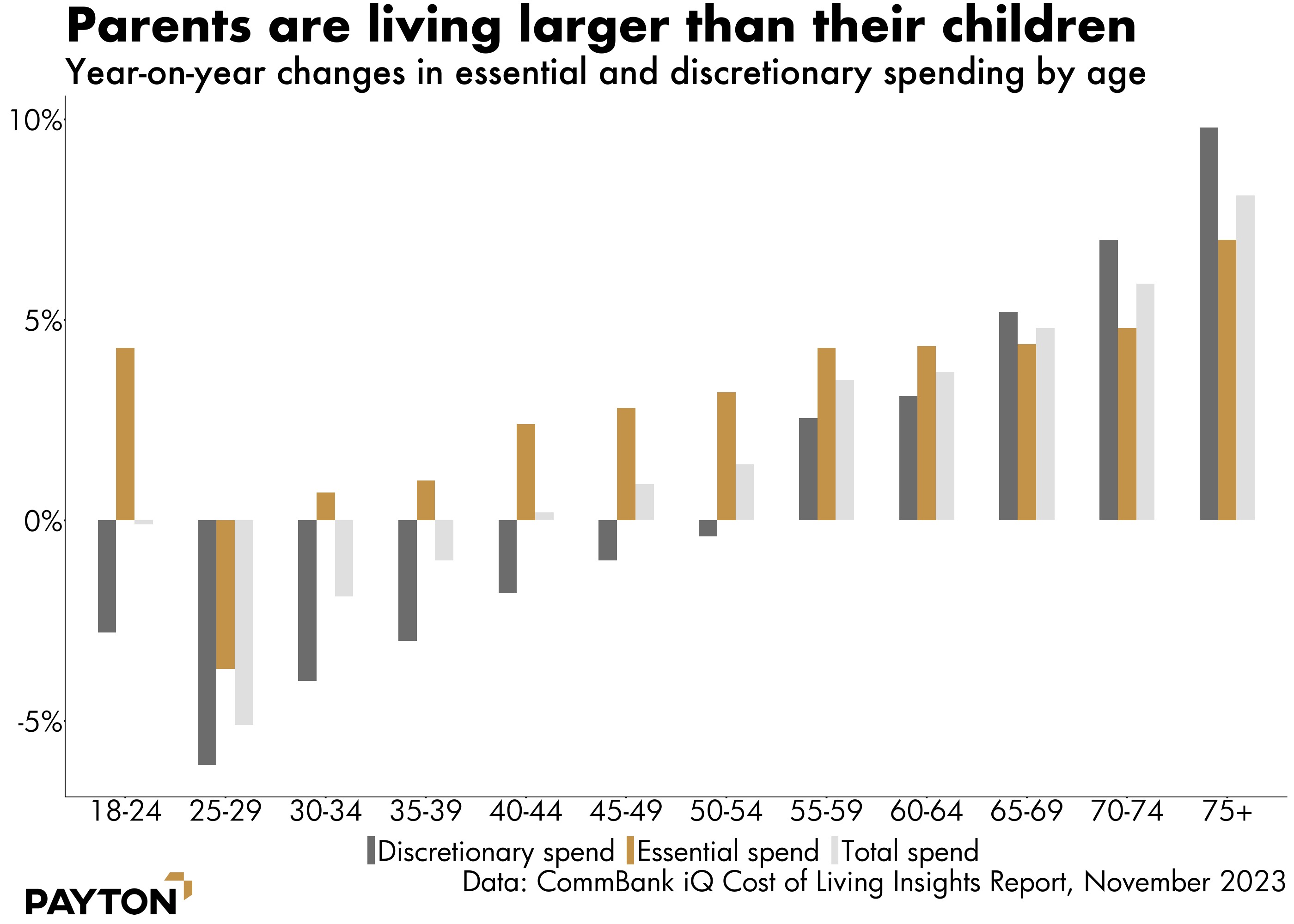

There is certainly evidence for this when we break down spending by age groups. Those aged over 60 are spending more on both discretionary items and essentials. But those aged under 25 are struggling to maintain their cost-of-living increases.

While rate rises are hard on (generally) younger households, any falls in property prices are often harder on older households. The RBA’s modelling suggests that households with large residential property exposure (either their own home or investment/holiday properties) reduce their consumption most in the face of a property price fall as they feel the wealth effect take hold.

Where are we now?

As this report is being written, global oil prices are under US$75 a barrel. That is their lowest level in months and heading towards half of their 2022 peak. What’s more, the lower crude price is flowing through to petrol prices. The RBA cited repeated supply shocks among its reasoning for the most recent rate hikes, saying repeated supply shocks can contribute to higher inflation expectations. So, a relaxation in petrol prices may help deliver a more relaxed central bank. Certainly, headline inflation should continue to drop.

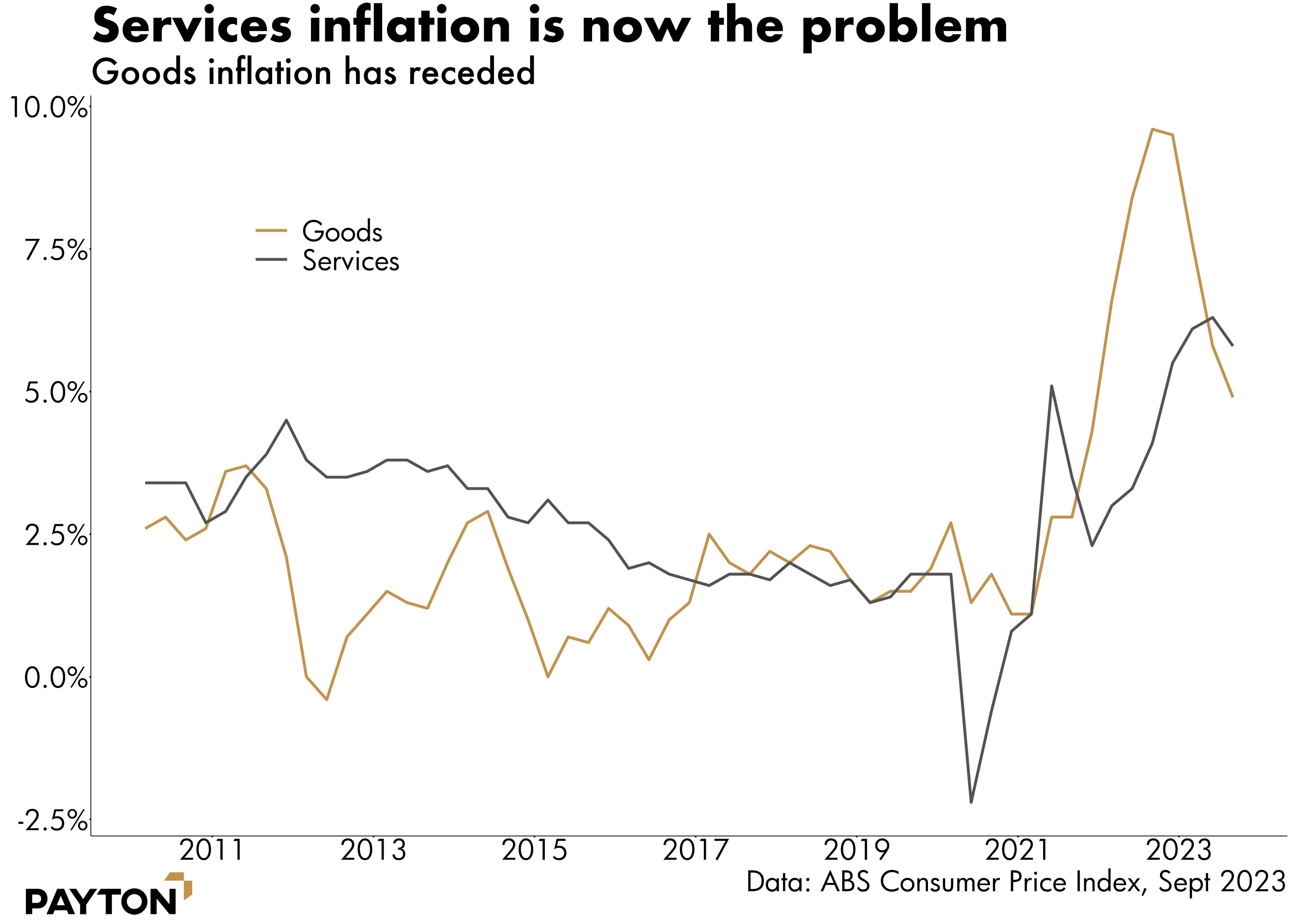

It takes time for oil prices to flow through to petrol prices, but some alleviation in terminal gate prices is already apparent at the time of writing. Petrol prices that subtract from inflation rather than adding to it would be a welcome situation, helping offset services price inflation that is proving slightly trickier for the RBA to combat.

Services inflation is persistent in the US as well as Australia, as global supply chains begin to hum again but wages and high demand cause local prices to creep up in advanced economies.

The American central bankers are worried about services inflation.

“With too few workers to fill the number of existing job openings, a continued increase in the demand for services may contribute to persistently high core services inflation,” said Federal Governor Michelle W. Bowman in a speech in late 2023.

The RBA is worried too but ascribes more of a role to firms not absorbing cost increases.

“High inflation was being underpinned by above-average price rises for a wide range of consumer goods and services. There was clear evidence – most notably for services price inflation, which was quite brisk – that this owed to domestically generated pressures associated with aggregate demand exceeding aggregate supply. This strength in demand was allowing firms to pass on higher costs for labour and non-labour inputs,” it said in the minutes to its most recent board meeting.

“Members noted growing signs of a mindset among businesses that any cost increases could be passed onto consumers.”

To make firms fear they could alienate their customers with price hikes, the RBA decided to do more to make consumers cost-conscious. And that required higher rates.

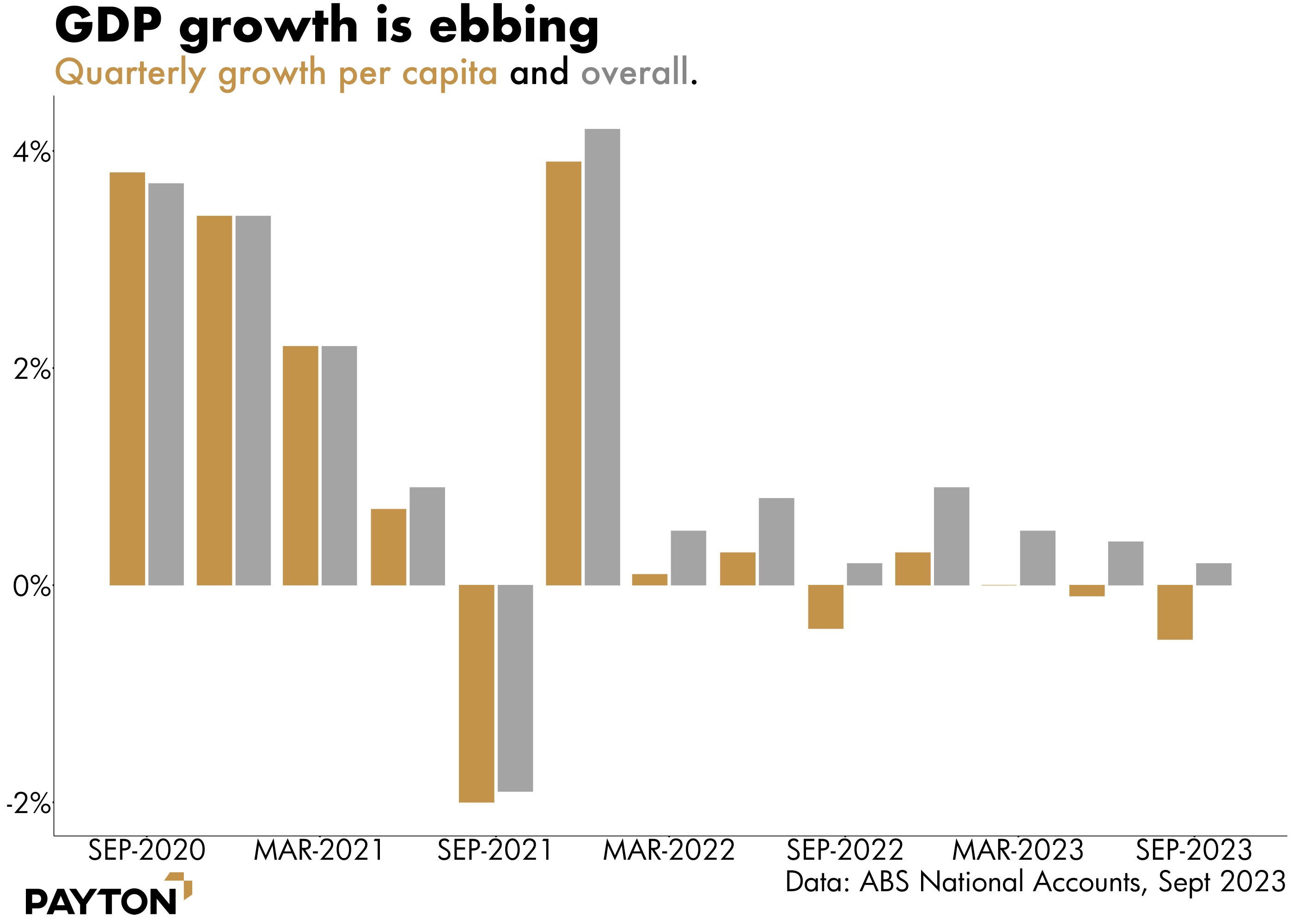

Rates have already done some work with the economy slowing in 2023, growing at a gentle pace despite a booming population. Per person growth fell in the last two quarters as the next chart shows.

What do we see

We believe that the residential property market is still well positioned coming into the new year despite the challenges it has faced throughout 2023. The rate of home loan arrears amongst the big five banks remains mercifully low despite higher interest rates. Australians do not tend to default on loans unless two conditions are experienced – their house is worth less than they owe, and they can’t afford to pay their mortgage. Right now, neither situation is common. Loan-to-value ratios have improved even further as recent house price growth has lifted home values. Fewer than one in 1000 mortgage holders owes the bank more than their house is worth, according to a recent RBA analysis.

And while mortgage repayments have soared, so have incomes. Australians are working more and getting paid more per hour, lifting incomes. There’s plenty of work out there, and underemployment is low. Household costs may have to be cut and people may be working long hours, but the mortgage will still get paid. What’s more, mortgage buffers are common: many borrowers have built up a year’s worth of repayments in their offset account or similar.

In summary, our view is that the residential property market is not at risk of a meltdown from its own internal dynamics nor from the projected path of interest rates and unemployment. What we are continuing to see is high rates of migration which will help in some part to underpin metro city prices.

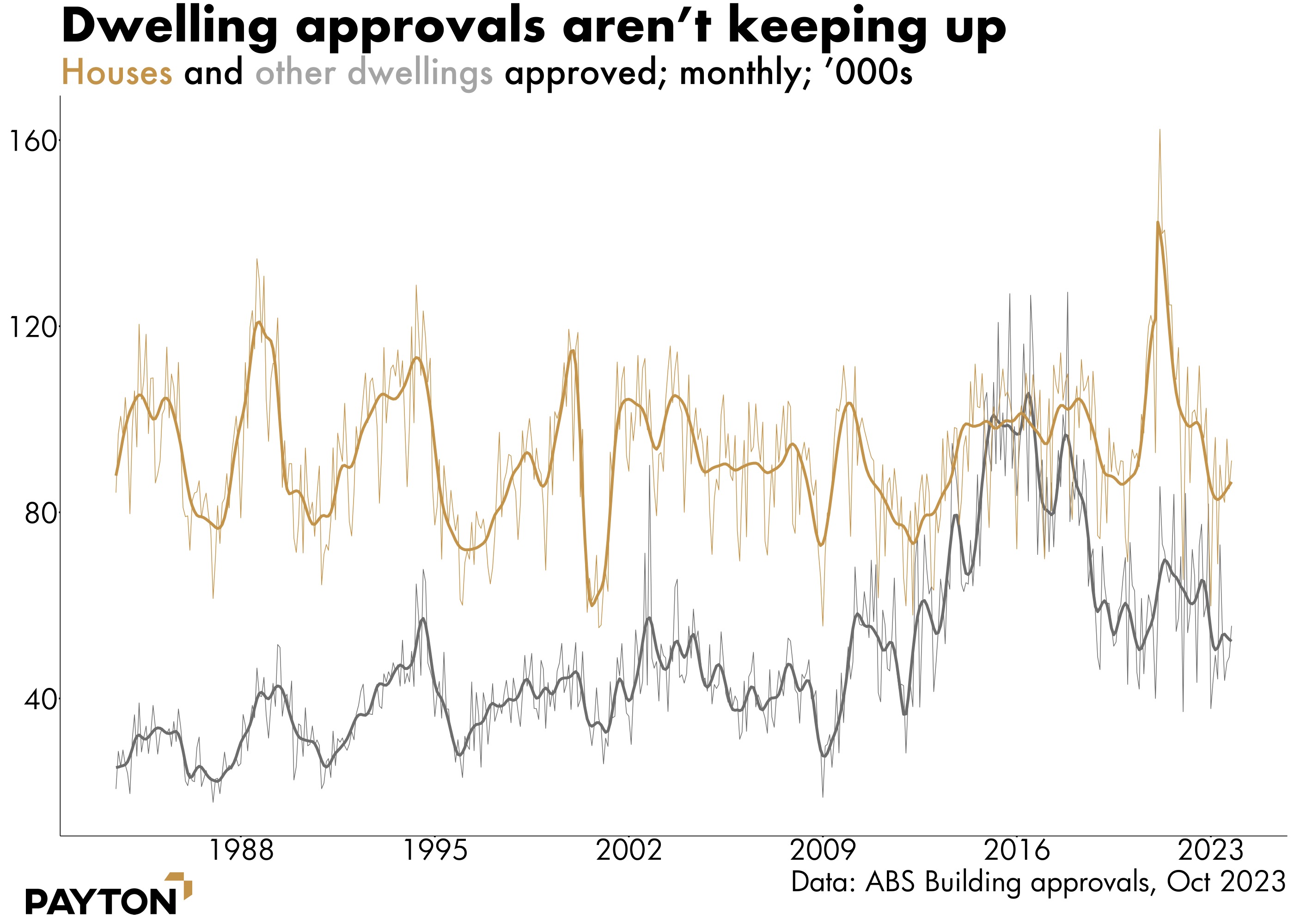

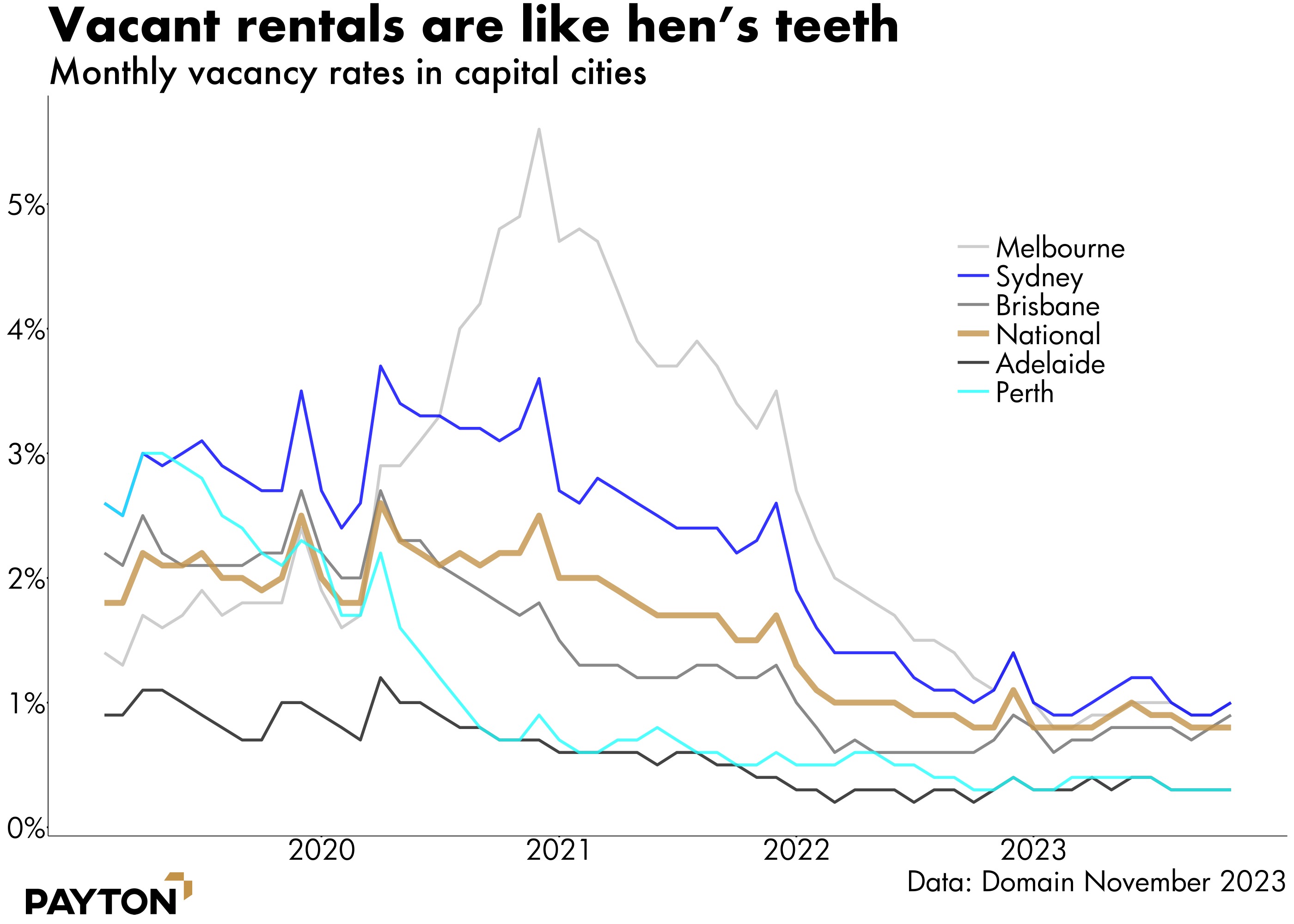

As the next charts shows, dwelling approvals are low by historic levels, even though rental properties are exceedingly hard to find.

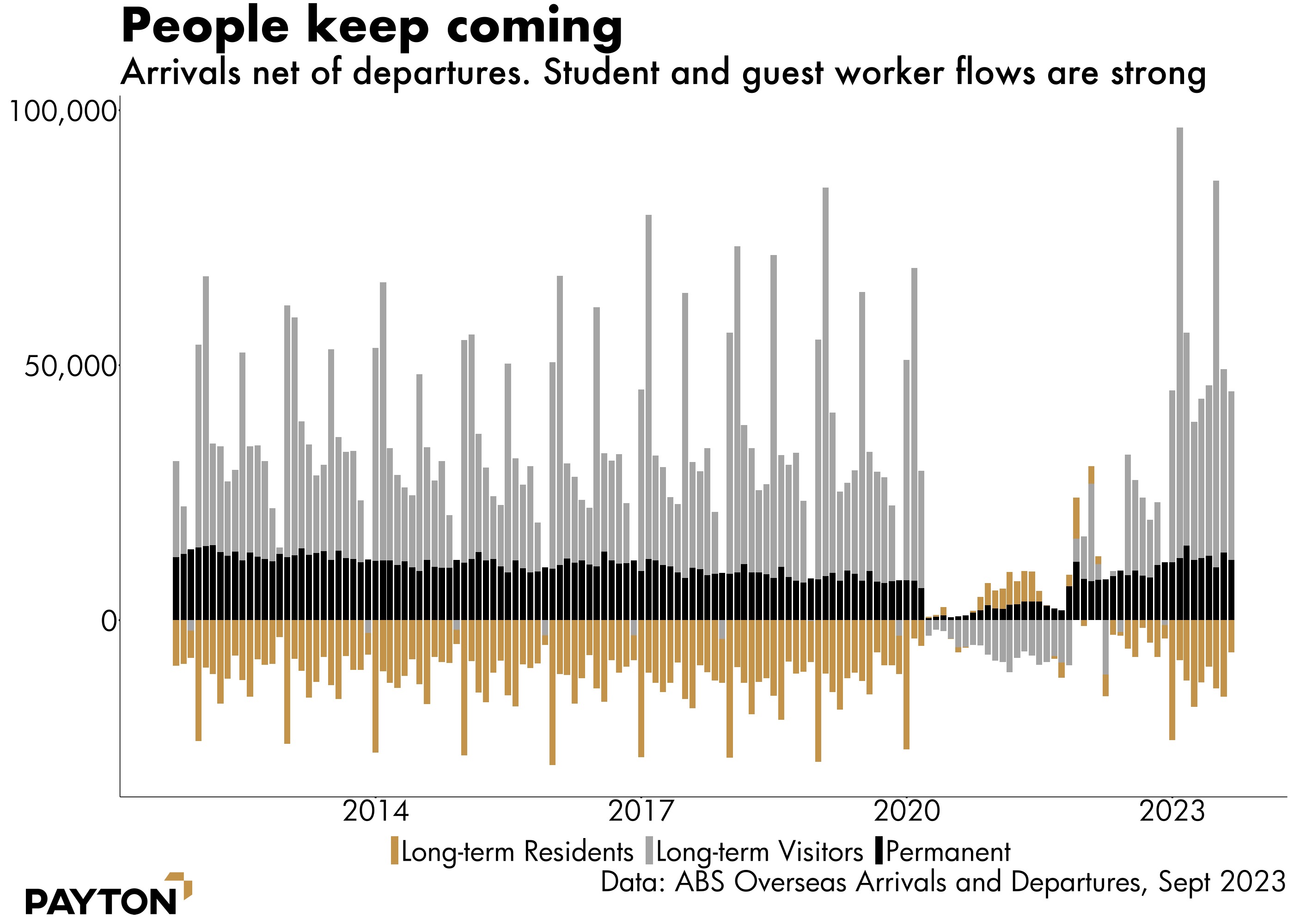

Migration is strong, with arrivals very much outstripping departures as the student economy rights itself.

The grey bars in the next chart show net inflows of long-term visitors, including students. Their very high numbers are a major factor putting pressure on the rental housing market, particularly eastern seaboard arrival cities like Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane.

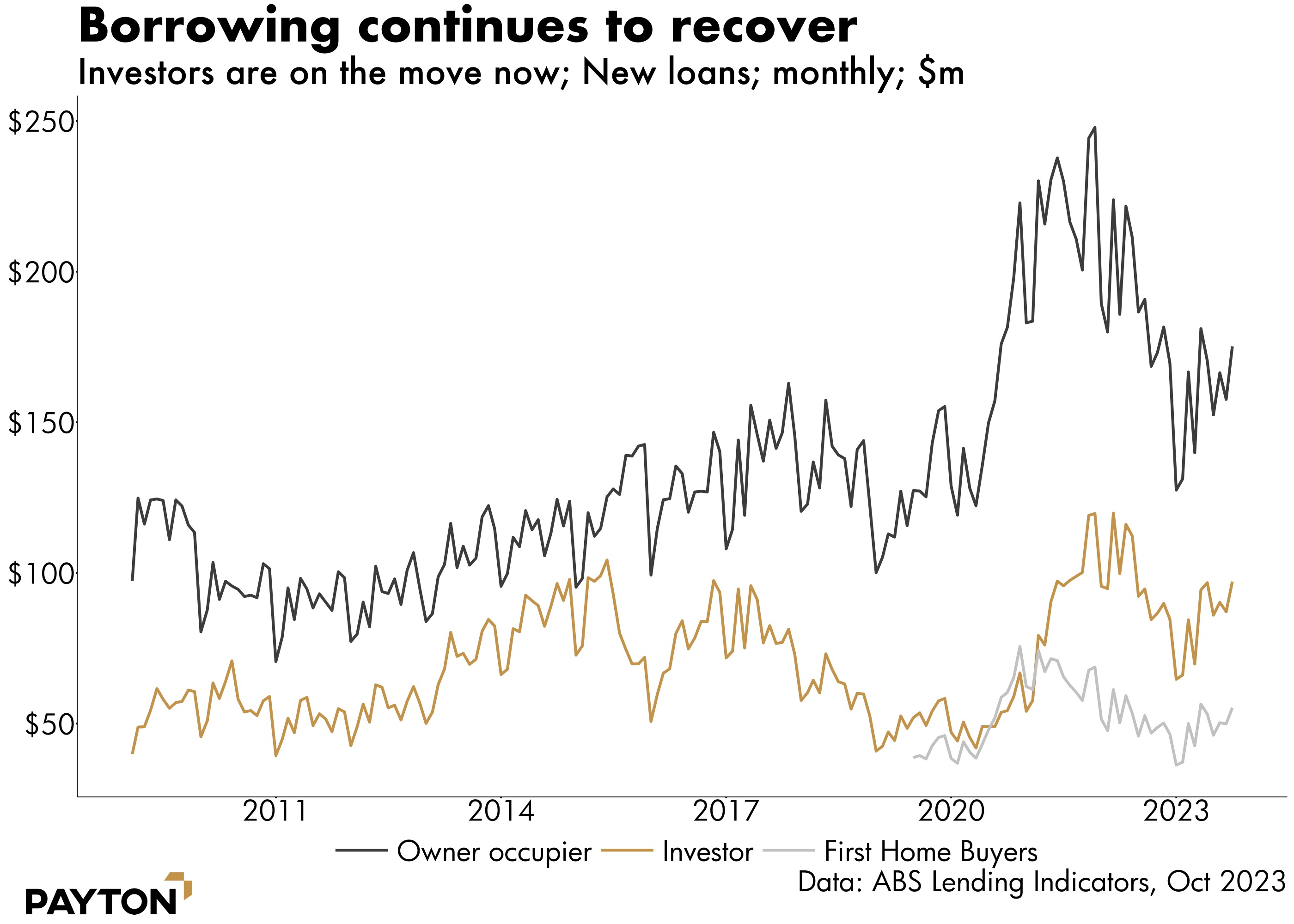

Rents in the last six months rose at a rate equivalent to a 10 per cent annual rise, and investors are certainly paying attention. The demand side of the market is strong, not only as measured by warm bodies, but also by lending. While price growth has moderated slightly in the recent months, lending data shows a continued upswing in borrowing by owner-occupiers and especially by investors.

The price of homes must in the long run bear some relationship to prices and wages in the economy. As the nominal price level of goods and services rises, and wages rise, houses become comparatively cheaper. An extended downswing in nominal house prices is less likely in a period of higher-than-usual inflation, so long as the inflation is matched by wage rises that keep pace.

On that front it is worth noting that the wage price index is now recording annual wages growth of 4 per cent, its highest level since 2009. Private sector wages growth is higher still.

China

The Chinese economy remains in a situation and the opacity of its financial markets is a cause for concern.

Evergrande and other developers are reportedly in trouble which has instilled a fear and general lack of confidence in the property market. While a collapse in any of the large property companies in China pose limited risk to the global financial system, they pose a big threat to the Chinese economy.

“In China, property developers remained under extreme stress. They had very limited access to funding from capital markets and banks had been hesitant to extend loans as defaults had risen,” the RBA noted in its most recent minutes. “Stress in the property sector had been contained thus far, but there were ongoing concerns about possible spillovers to other parts of China’s financial sector.”

A Chinese economic meltdown is something the world is not ready for. The last time China’s economy shrank it was a global irrelevance. Now it is the second largest economy in the world. The effects would be felt here for certain. However, the lessons of the pandemic should be borne in mind and second-round effects should be considered carefully. Crises come with responses and in recent history, China’s response to weakness has at times been very fortifying to Australian export prices.

Recent economic and political easing of tensions between Australia and China has certainly been welcome for our barley producers who are exporting in large volumes again. Winemakers expect to join the party soon, with a review of Chinese tariffs underway across a number of Australian exports.

Whilst China’s situation remains to be resolved, the American economy is looking stronger and resilient as it navigates it way out of the post pandemic reflation. It has seemingly achieved the much-vaunted “soft landing”, reducing inflation down to 3.2 per cent while dodging a recession and keeping unemployment under 4 per cent.

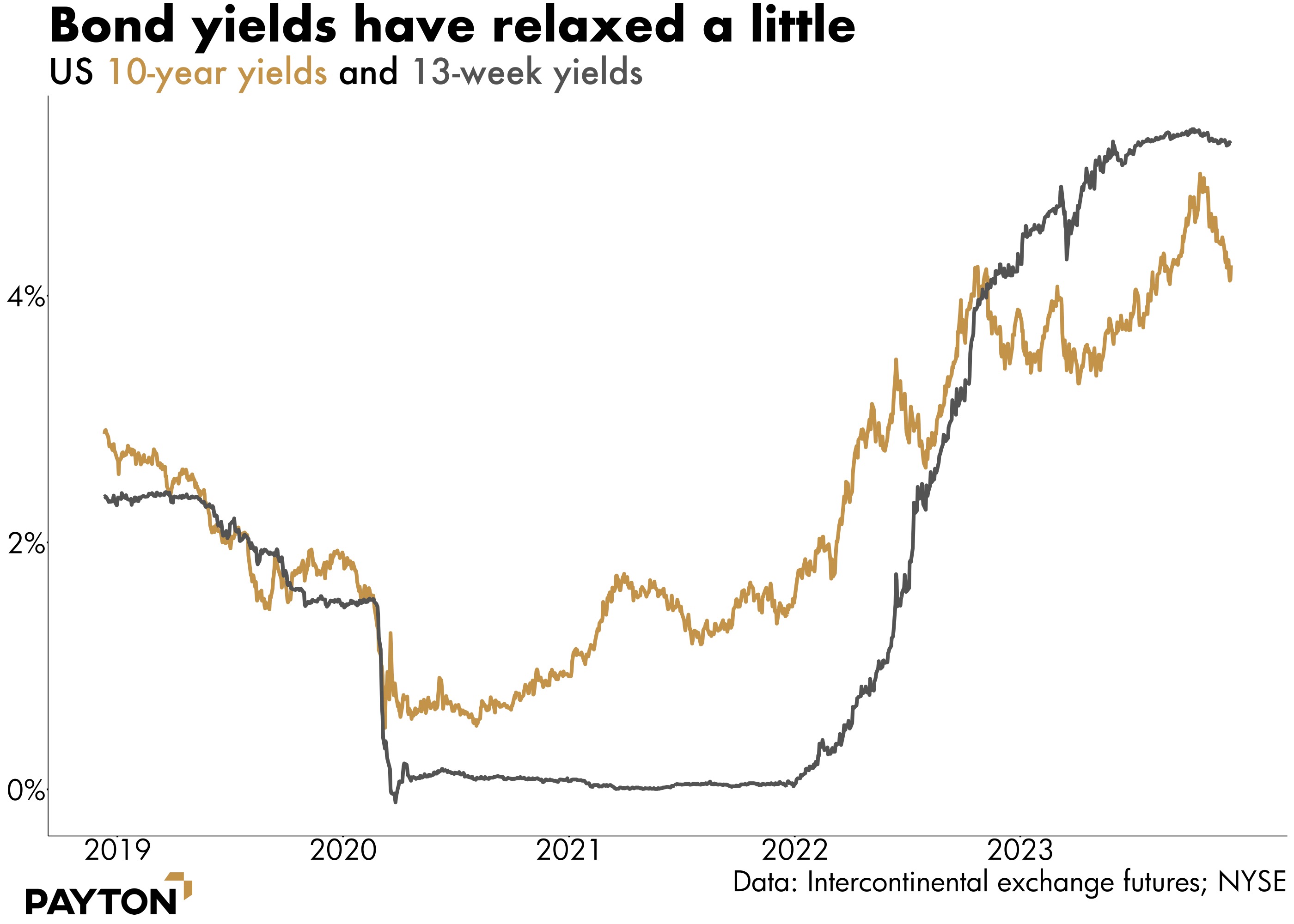

US Bond yields are falling again, and property prices are rising. S&P Corelogic has US house prices up 3.9 per cent, with higher growth in big cities like New York (+6.3 per cent) and Los Angeles (+5.2 per cent).

If Australia follows the US into seemingly clear economic water – which is our view – the conditions are set for a strong period of property market activity with lots of building, lots of investor activity, and steady price appreciation.