3 big risks investors forgot to price in

For the best part of a decade, markets have ‘climbed a wall of worry’, eking out returns despite an ever-growing list of worries. But more recently, investors learned to stop worrying and love the equity markets. Bushfires, Brexit, the bombing of Saudi oil assets, missiles in Iran, sovereign defaults, and even the possibility of a global pandemic. None of this seems to be able to shake the euphoria of the market in 2020. But which ones should we be concerned about, and what’s not worth losing sleep over?

In this Collection, we hear from four experts about the biggest risk that’s not being priced into markets today. Responses come from Damien Klassen, Nucleus Wealth; Seema Shah, Principal Global Investors; Jonathan Rochford, Narrow Road Capital; and Shane Oliver, AMP Capital.

Markets not yet pricing in coronavirus risks

Shane Oliver, Chief Economist, AMP Capital

The biggest risk for markets is that the coronavirus outbreak takes more than a few months to bring under control and so the hit to Chinese, global and Australian growth drags into the June quarter. Markets appear to be priced for the scenario that the outbreak and hence economic disruption will be short-lived and that policy easing inside, and outside of, China can offset this, and turbocharge the rebound. This is our base case too (with 75% probability).

The risk that it takes longer to control is not insignificant. It has also come along at a time when markets are vulnerable to a bit of a correction after the huge rebound seen through last year, particularly since the last decent correction back in August.

So it wouldn’t be surprising to see a bit more volatility in the short term given ongoing uncertainty around the coronavirus, particularly given the high likelihood of a run of weak economic data and profit warnings flowing from the virus in the month or so ahead, even though we ultimately see it coming under control, allowing shares to have a good year.

So ultimately, I would tend to see any short-term volatility and weakness as providing a buying opportunity.

It's not the black swans, but the green ones you should watch for

Seema Shah, Chief Strategist, Principal Global Investors

So far in 2020, the world has been rocked by three significant events:

- Bushfires in Australia,

- US/Iran tensions, and

- The coronavirus.

The latter two events have sharply impacted markets, if only for a short period of time in the example of US/Iran tension.

Yet the Australian bushfires which have wreaked not just short-term havoc, but longer-term devastation on large areas of Australia have been barely registered by markets.

Climate damage will repeatedly and increasingly impact large areas of the world, inflicting significant damage on communities and markets. Yet, this “green swan” event, which is a known risk, is rarely registered in broad asset prices.

Economic data will even tend to look positive in the immediate aftermath of a climate catastrophe due to reconstruction spending in the affected area. However, this misleadingly conceals the negative impact on the local economy and on supply chains – a topic which, in the instance of the coronavirus, the market has become fixated on.

Grey and black swans are feared by investors. Markets would also do well to take more notice of the “green swan” phenomenon, which is likely to grow more devastating and wide-reaching with each year that passes.

Governments and central banks have exhausted their options

Jonathan Rochford, Portfolio Manager, Narrow Road Capital

Few investors are pricing in the possibility that many governments, both national and regional have almost exhausted their fiscal and monetary policy responses.

The recent defaults by Argentina, Venezuela and Puerto Rico are being ignored. Weaker sovereigns are having little trouble in issuing more debt, despite having no credible pathway to balanced budgets, let alone repaying their debts. This is a strong sign that investors are focusing more on the short term return on their capital than the long term return of their capital.

In many developed economies, the unfunded pension promises are even greater than the explicit debt liabilities. This acts as another handbrake on fiscal stimulus, as the payments to retirees step-up each year. Few lenders to governments realise they are third in line to be paid, after the provision of necessary services and the pensions owed to retirees.

The RBA is in the same boat as many other central banks with little ability to cut the overnight rate further. The example of Sweden, which has abandoned negative interest rates after recognising that the “remedy” was worse than the disease, has made this point clearer. Easy monetary policy has been a raging success in inflating asset prices and credit bubbles but has done much less to increase CPI. The RBA recently acknowledged this in making the case for why it is reluctant to cut further.

Markets have been conditioned to believe that governments and central banks have their back (Greenspan/Bernanke/Yellen Put), but when the next downturn arrives governments may have already exhausted their capacity for fiscal and monetary stimulus.

The point of no return

Damien Klassen, Head of Investments, Nucleus Wealth

The biggest risk to markets is COVID-19 (the coronavirus). But probably not for the reason that you think. There are three main risks from COVID-19, one linear and two non-linear risks.

By non-linear I mean that it is a bit like driving along the edge of a cliff. If you were 10 metres away from falling off or 10 millimetres, the outcome is the same: you survived. But go just that little past the edge, and you reach a point of no return.

Linear Risk 1: Insufficient Stimulus.

The market has been happy to "look across the valley" of any downturn from the virus. On the other side of the valley, it expects a massive Chinese stimulus package and bid ups stocks on that expectation.

Perversely, it seems the market is pricing more bad news as meaning the Chinese stimulus package will need to be even bigger. Which will be even better for the stocks involved.

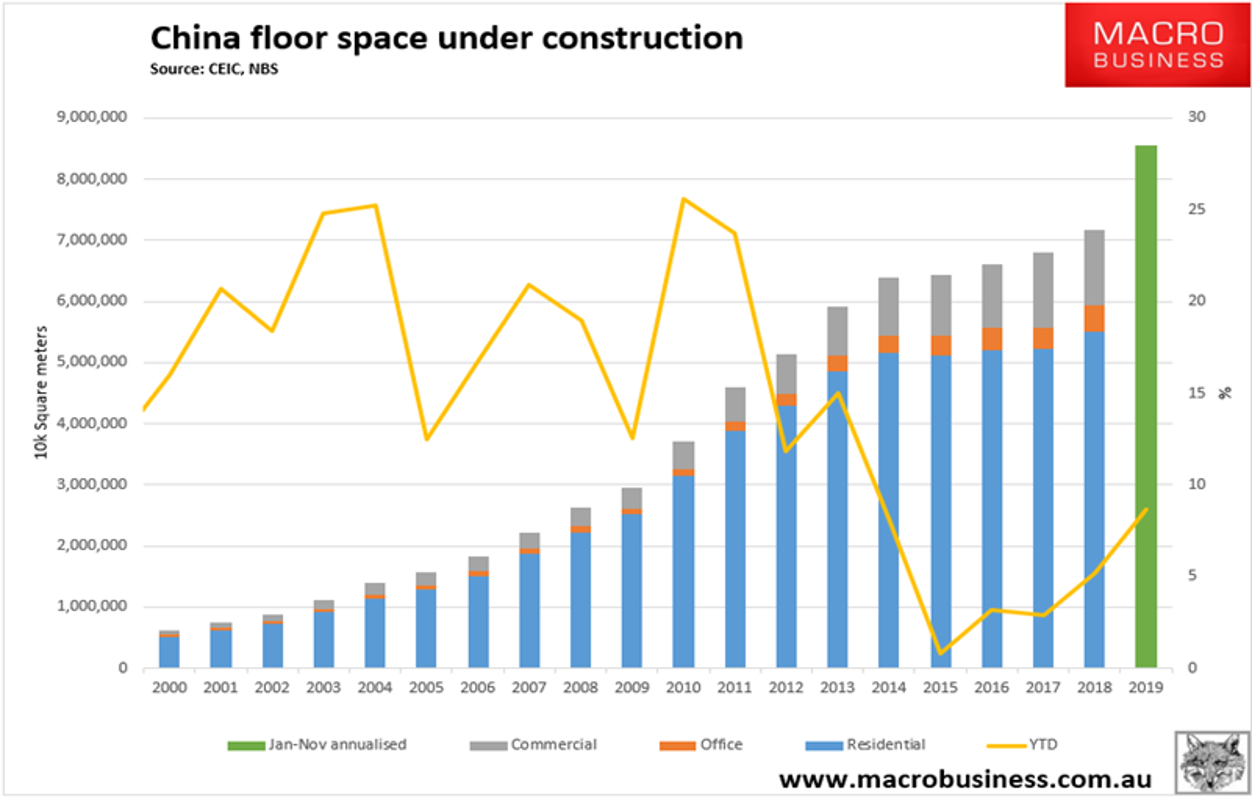

The risk is that China can't stimulate much harder - they are already building at incredible levels. In 2008 the Chinese premier warned of unbalanced growth too dependent on construction. Construction is now 3x higher:

And so the major risk is that more building stimulus won't be enough to replace the lost demand.

Non-linear Risk 2: Global Pandemic.

This is the risk you likely expected. Indications are that COVID-19 kills about 1-2% of people who it infects. Hong Kong's leading public health epidemiologist suggested that, in a pandemic, about 60% of the world's population would be affected. We are talking 50m people dead.

It is too early to panic based on this risk, but it is also far too early to dismiss the risk.

The non-linearity comes from how the virus spreads. The likelihood is that either:

- The virus escapes the Hubei province and spreads to the rest of the world or

- The virus is contained in its early stages outside of Hubei

There is almost no middle ground between the two.

Non-linear Risk 3: Debt Crisis.

This is not being priced in at all, despite far more indications that it is a major risk. We know:

- Corporate debt is at all-time highs

- Many companies run "just in time" inventory and have very little slack in the system

- The end of the corporate debt cycle almost always results in a recession

- There is a supply shock already coming for companies with operations in China from shutdowns and quarantines

- At the same time, there is a demand shock starting to unfold for companies dependent on Chinese demand from shutdowns and quarantines

- Some small companies are already folding, after just a few weeks of China shutdowns

The risk that markets are not pricing is a wave of company defaults from companies that are overleveraged and reliant on either demand or supply from China.

The non-linearity is similar to the pandemic. If there are enough defaults (or one or two large, high profile defaults), then:

- interest rates will increase in the corporate debt market

- loans will become harder to get and/or rollover

- this will mean other companies will also default

- interest rates will go even higher, loans harder to get

- and so on, spiralling into a debt crisis.

In conclusion

While it's important to keep key risks like these on your radar, panic is rarely the appropriate response. By being aware of the risks and managing them to a reasonable level, you can invest for the long-term without losing sleep.

Click the "follow" button below to be notified when I publish part two of this series, where we discuss the issue of COVID-19 in more detail.

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

1 topic

4 contributors mentioned