3 parts of the economy keeping inflation high (and making the RBA's job tough)

“Now people, stop what you're doing, and listen to what I have to say, cause inflation is in the nation and it's about to put us all away.” - Inflation blues classic. Ernest Jackson, Sugar Daddy and the Gumbo Roux

For many years, we have been card carrying members of the deflationista club. In the decades preceding COVID, long term drivers of prices were overwhelmingly lower, exerting downward pressure on inflation. This forced central banks to battle against deflation even as economic growth trundled along at a reasonable pace. We do not need to rehash the well-known forces that underscored this trend, namely: globalisation, access to low-cost manufacturing, technology, debt levels and demographics.

There are many arguments to mount as to why these forces haven’t gone away so much as been swamped by cyclical pressures and supply chain headaches. Let us assume that is true, and further that debt levels, particularly in developed economies, are only rising, which presents a brake on future potential growth and inflation. And yet, here we are in the fourth year post-COVID, and whilst inflation has certainly come down, the reality is dawning that it is unlikely to revert to the sub-2% era we witnessed pre-pandemic.

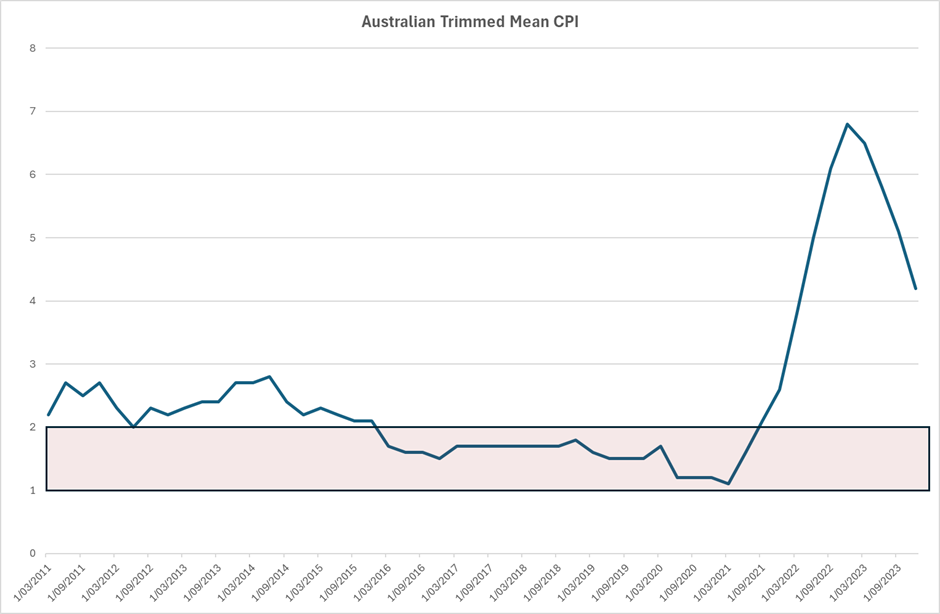

The chart below highlights that the RBA’s preferred core inflation measure, the Trimmed Mean CPI, languished well below 2% (shaded red) from 2016 for the four years preceding the pandemic.

Source: Franklin Templeton, Bloomberg Data

During this period from ~2016 onwards, some of today’s more topical inflation components were either in or near deflation.

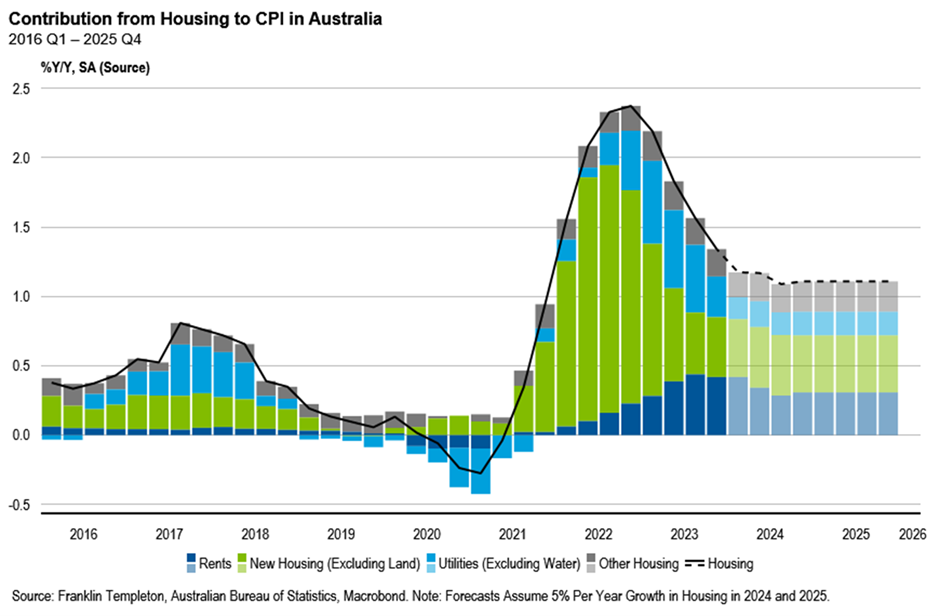

My colleague Josh has pointed out that the broad ‘shelter’ component of the CPI basket accounts for ~20% of all items. This consists of rents, home construction costs and utility costs. The chart below shows the contribution to CPI of these items over time and highlights that rents, and utilities in particular, were either adding close to nothing or actually deflating the CPI measure just a few years ago.

Over the last few years, we can see these “shelter” components surged and added a significant contribution to the CPI basket. In fact, home construction costs boomed to adding nearly 2% to CPI just by itself.

Josh now postulates, what happens if these three items settle down to ‘just’ 5% over the next couple of years? The chart below shows that under this scenario, their collective contribution to the CPI basket goes to ~1%. Which may not sound like much but is a big turnaround from the pre-COVID years when their contributions barely registered.

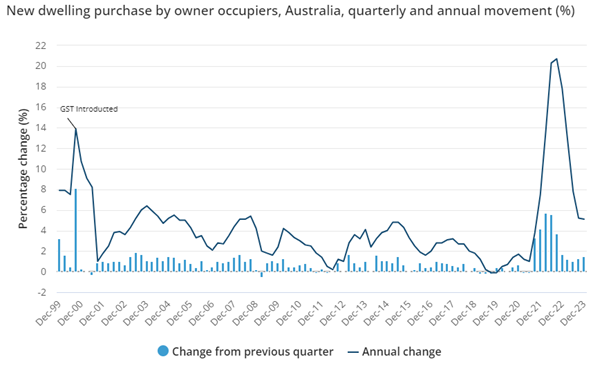

Construction costs have eased from the crazy levels of 2021/22. But with governments everywhere scrambling madly to figure out how to stimulate building new homes and competition from large scale projects keeping wage costs for skilled trades firm, we can see construction CPI staying firm for a while.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics; Franklin Templeton

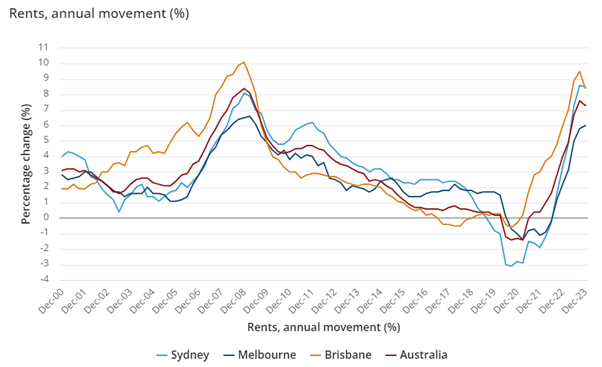

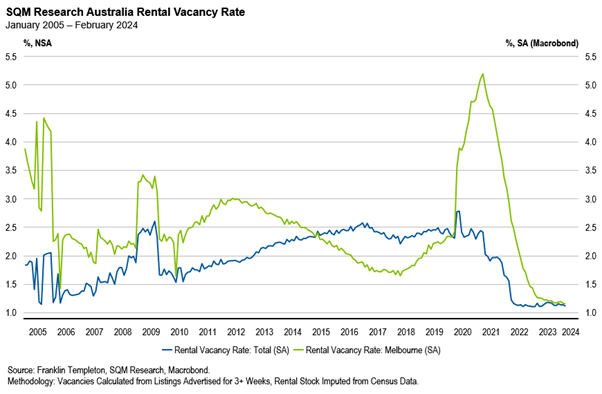

Rental inflation is persisting more than home construction costs. This should surprise no-one. In Melbourne, the latest data suggests that number of actual dwellings available for rent is a mere ~6,000. In a city of more than 6 million, this is approaching apocalyptic levels of tightness. Overlaid with very high levels of population growth, we see rent inflation as a problem that won’t recede easily.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics; Franklin Templeton

This is manifest as one of the lowest rental vacancy rates on record. Right now, you need a microscope to see it. This issue is exacerbated by the doom loop landlords face of rising costs from interest rates, land taxes, etc which is reducing the supply of properties to the rental market even as demand surges through population growth.

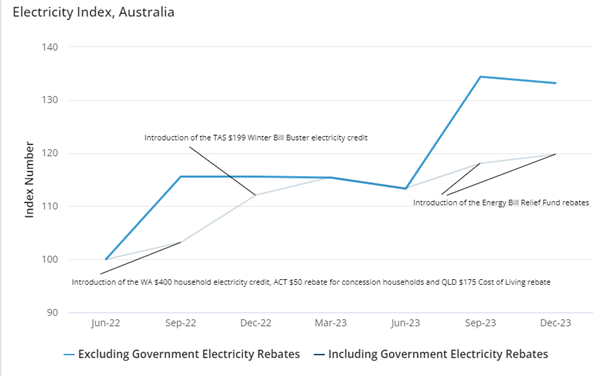

Finally utility costs are likely to be volatile. Government ‘cost of living’ subsidies have suppressed the price rises that otherwise would have flowed through as highlighted by the ABS data below. As for the energy transition, we simply don’t know how that works out. The fact that southern states look like they could face a major gas shortfall in the next 2 years according to the Australian Energy Market Operator is but one challenge now barrelling down the tracks.

The reality is we don’t know where these components will settle over the next few years. What we can suggest with reasonable confidence is that the idea that this core ~20% housing related component of CPI is going to go back to the anaemic levels pre pandemic seems unlikely. The key conclusion is that whilst the RBA probably does drag CPI back into the 2-3% band, the likelihood that we revisit the days of inflation persistently starting with a 1 is looking remote.

The RBA and other central banks will cut rates over the next 1-2 years. A lot of that is already priced into markets. Duration can work modestly but it’s unlikely to shoot the lights out, unless an accident happens, or some other left field event resets the narrative.

Many forecasts see policy rates in Australia and the US getting down to the ~3-3.5% level. It could be a bit higher or a bit lower but that’s about it. That means markets can take yields a little lower but not materially so. The good news is that a good proportion of fixed income total returns look to set to continue to come from, well, yield. And maybe that’s not a bad thing.

.png)

1 fund mentioned

.jpg)

.jpg)