3 questions about bond markets you were too afraid to ask

While investors were still reeling from the ongoing chaos in equities markets, the bond markets nudged their way onto centre stage late last week.

Trump and US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent have repeatedly called for lower treasury bond yields as the US struggles to repay its mounting debt.

After bond markets pushed rates higher, Trump’s hand was arguably forced, leading to a 90-day pause on his recently announced tariffs.

But why does this matter? To put it simply, bonds are the beating heart of markets - the primary source of liquidity that is the lifeblood of global trade.

So when bonds start acting up, it’s time to pay attention.

But if you don’t know your TMUBMUSD10Y from your TMUBMUSD02Y, or are simply struggling to keep up after a crazy week, we’ve got the expert take on what’s been going on and what history tells us will happen next.

What has happened to bond markets this week?

After equity markets zigged and zagged with every development in Trump’s tariff war, bond markets finally got in on the action late this week with fluctuating yields and fears of a liquidity crunch.

While a frothy stock market was the obvious first victim of Trump’s escalating tariffs, bond markets couldn’t escape the heat.

"Overvalued equity markets were primed for a retracement and bore the brunt of the initial selloff,” said Darren Langer, Co-Head of Australian Fixed Income at Yarra Capital Management.

“However, as concern grew around the broader implications of Trump’s policies, bond markets joined in, culminating with two of the more volatile days I’ve experienced in bond markets.”

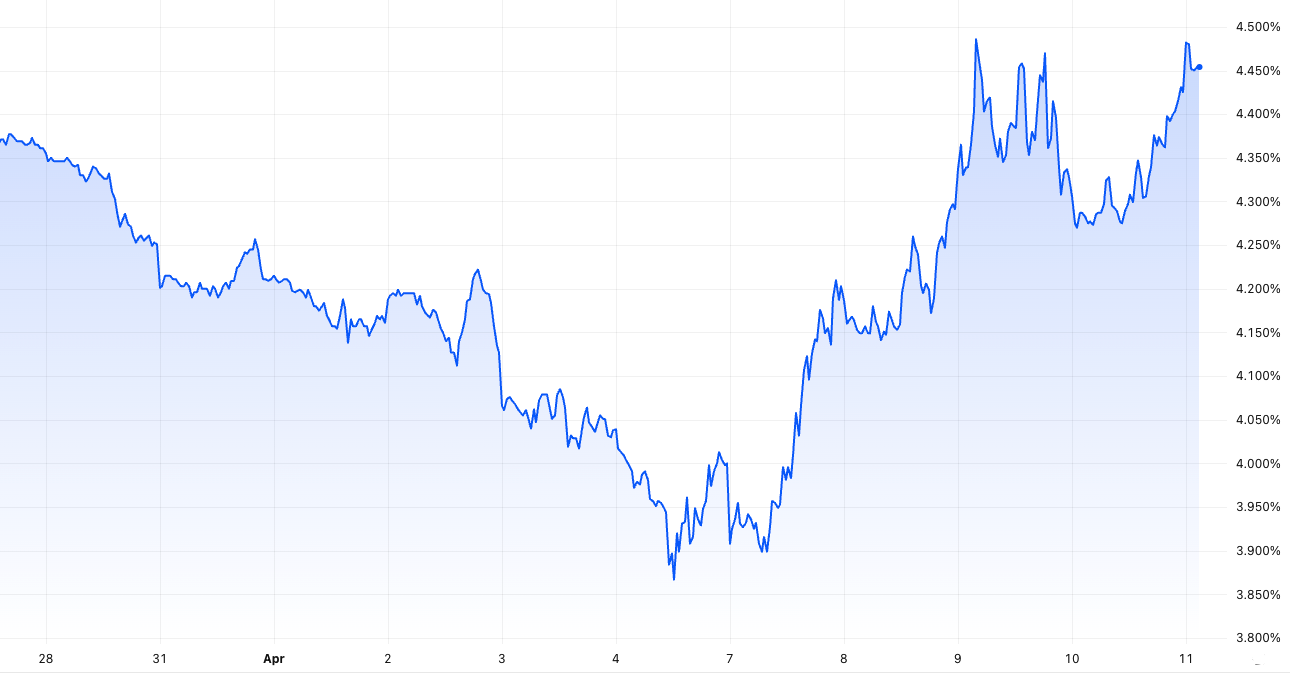

By Friday, the benchmark US 10-year bond yield was sitting around 4.45%, having dropped below 3.9% and then surged as high as 4.51% within a matter of days.

Widely seen as the quintessential safe haven asset, this level of volatility is rare for government bonds in particular, and points to ongoing fears around a potential global recession or even stagflation - where growth slows but prices keep rising.

Trump’s yo-yo approach to tariffs has exacerbated the situation, and left even the bond markets in a state of flux as it tried to get a handle on where things go next.

"Significant uncertainty, such as that experienced during this market episode, creates uncertainty around the risk of default and demand for these investments, which has caused large moves not only in the base or risk-free rates but also credit spreads,” said Jay Sivapalan, Head of Australian Fixed Interest at Janus Henderson.

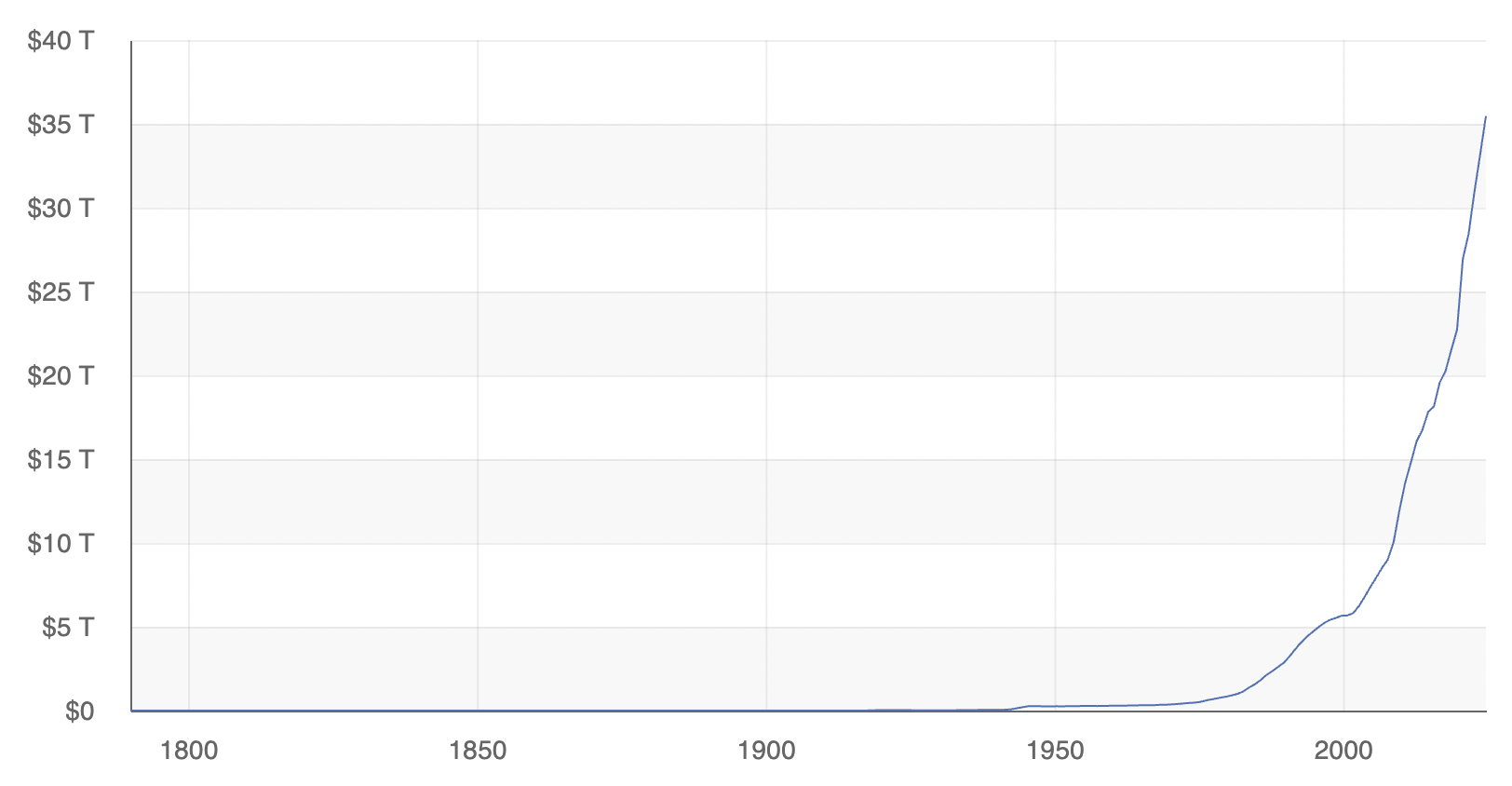

Governments use bonds as a way to generate funds, with the US Treasury bond market individually worth US$29 trillion. 10-year bonds are the most popular, and as the name suggests, reach maturity after 10 years and need to be paid back.

With US debt at unprecedented levels, more bonds need to be issued to simply repay previous bonds.

And with the US government needing to repay trillions of dollars in bonds due to emergency borrowing during Covid, a higher bond yield spells bad news as it makes the cost of borrowing higher and threatens the US’s reputation as a bond issuer, something that has been reflected in bond markets this week.

“Longer maturity yields went higher on longer term inflation concerns and fears that large offshore holders of US treasuries could abandon the US market at a time when even more debt issuance was likely to be needed,” said Langer.

Despite these concerns, the markets scooped up US$39 billion in 10- and 30-year US bonds when they went to auction on Thursday as bond investors showed a willingness to flock to quality credit.

“The wheat has been separated from the chaff, with investors pursuing high credit quality over riskier or less liquid fixed interest investments,” said Sivapalan.

“Markets have witnessed their biggest drawdowns in higher yielding sectors, such as loans, global high yield and ETFs/LITs linked to less liquid sectors. Meanwhile, government bonds, state government bonds and high quality corporate bonds have yet again risen to the occasion.”

What role do bonds play in the wider economy and markets?

“Bond and loan markets are important as they facilitate credit creation in an economy and provide the basis for valuing other assets,” says Langer.

Because of their ability to raise taxes and print money to cover existing debt, government-issued bonds are seen as a relatively risk-free investment (in terms of default risk) and play a number of crucial roles.

"A well-functioning bond market supports financial stability, long-term economic growth and the efficient allocation of capital." - Darren Langer

“Governments use bond markets to smooth the financing of infrastructure and provide services without needing to frequently adjust rates of taxation,” says Langer. “The shape of bond yield curves may also provide information on expected inflation as well as the likely direction of short-term interest rates.”

“Treasury bonds, particularly the 10-year Treasury bond, are pivotal within the global financial system due to their liquidity and role as a benchmark for setting prices for capital formation,” says Sivapalan.

“They influence consumer interest rates on mortgages, credit cards, and auto loans, and serve as a base rate for corporate borrowing costs.”

Have we seen something like this before? And what can we expect next?

While we have faced similar volatility in recent crises, namely Covid and the GFC, the specifics here are different. Add Trump’s unpredictability to the mix and it remains to be seen how it would be handled this time.

“Every crisis is different even if markets initially react the same way – selling riskier assets and moving to ones that seem safe (often gold, government bonds and cash) which we call the ‘flight to quality’," says Langer.

“During the GFC and to a lesser extent the COVID crisis, central banks worked together to engineer a solution and the US Federal Reserve (with the backing of the US Treasury) was central to making a solution work,” said Langer.

“In a world where the US no longer fills that role and where countries adopt a ‘beggar thy neighbour’ approach, the potential for a more systemic issue arising is much greater and the solution more difficult to achieve.”

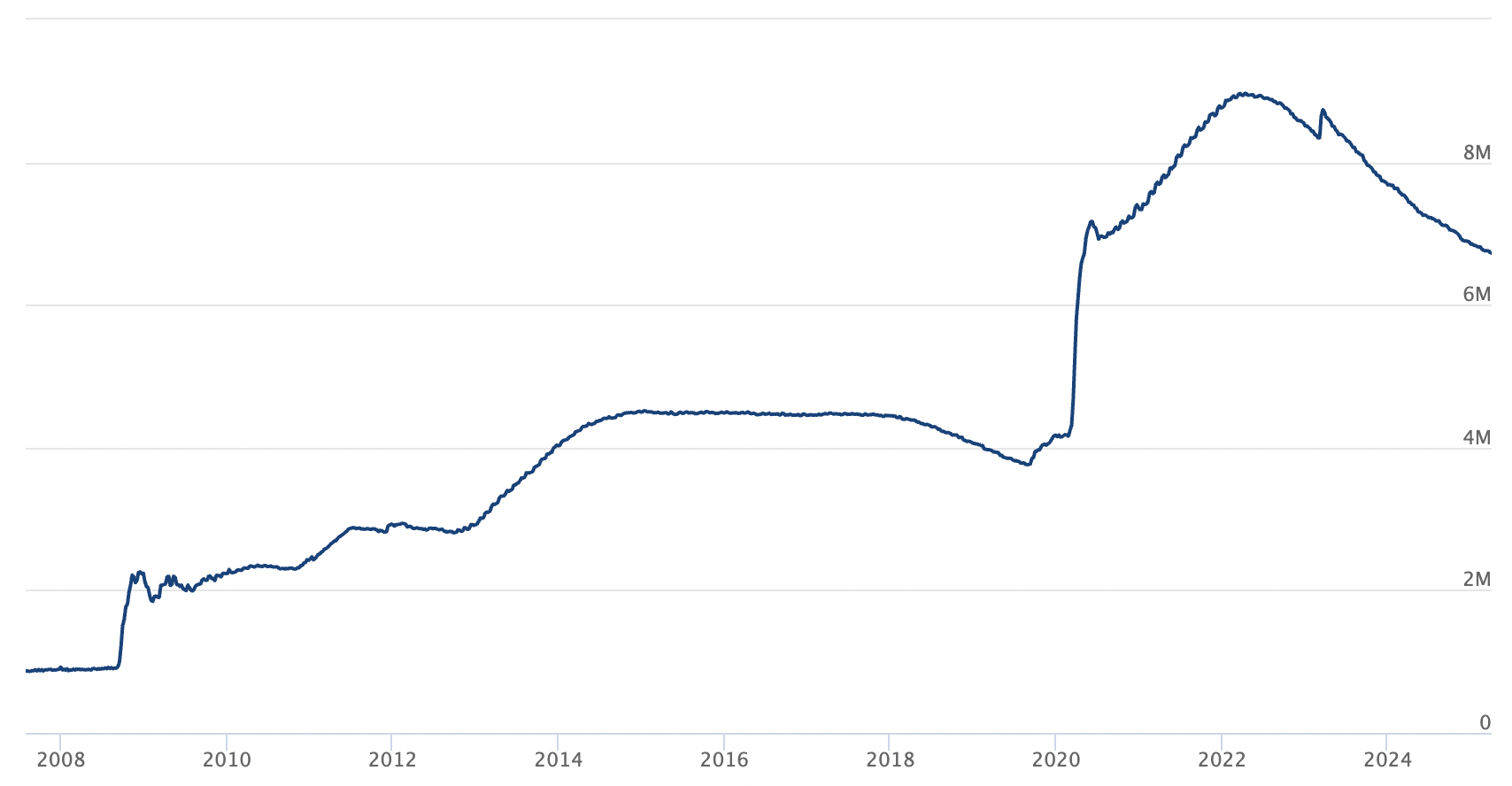

Quantitative easing (QE), the response to the Covid liquidity crisis, is partly to blame for what we saw in markets this week, says Langer, by pushing rates so low that investors chased higher and riskier yields elsewhere.

“This event, although triggered by President Trump’s tariff threats, was largely the result of overvalued risk markets and the long-term undermining of investor support for government bond markets due to reliance on QE,” said Langer.

While fiscal stimulus still remains the likely response if growth does slow, governments may not be willing to replicate the approach adopted during Covid.

“Central banks will have a much higher threshold for the use of unconventional policies such as quantitative easing,” said Sivapalan.

So while uncertainty remains, so does opportunity, especially in the bond markets.

“Liquidity, whilst less ideal at present, remains reasonable compared to COVID and the post GFC period,” said Sivapalan. “We are again already finding good opportunities for investors that are likely to result in outsized returns through this crisis by focusing on fundamental quality and attractive risk-adjusted rewards in defensive names.”

“History reminds us that no two crises are the same but that fortune favours the brave.”

3 topics

1 contributor mentioned