5 reasons value stocks could be set to run

The COVID-19 pandemic has further ingrained the idea that disruptive businesses represent the economy of both the future and of today. It has also helped embed the idea that the reweighting of major investment indices from old economy (value) sectors to new economy (growth) sectors is justified.

But to fully accept the above narrative is to forget that stock markets represent nothing more than investors’ assessments of how future cash flows will be distributed. Arguably, the kind of divergence we have seen between value and growth can only be possible if market participants deeply believe that traditional value businesses are structurally disadvantaged. When this has occurred in the past, it has historically proved to be the most dangerous time for investors who seek comfort in the safety and agreement of the crowd. But what exactly might prompt the prevailing market narrative shift in favour of value businesses?

To understand what might make investors question the price they are paying to own the most highly-favoured businesses, it’s important to first understand which growth businesses the market has favoured so enthusiastically and why.

The first growth darling is the so-called “moat” business, characterised by:

- an established company that typically built up its market dominance over several decades through competent management;

- a recognisable, world-leading brand;

- the creation of ever more innovative production processes.

Due to these deeply embedded strengths, moat businesses generally continue to enjoy strong and persistent returns on capital. The market understands the strengths of these businesses and values the profits and cash flows they produce more than those of other companies. This is because the market usually believes them to be extraordinarily durable and possibly permanent.

The second type of well-loved growth business is the “disrupter." This younger business is characterised by its rapid sales growth and acquisition of market share, often from inflexible, bureaucratic operators. Typically, these businesses produce little or no profit, but investors are happy to support and finance them because they reinvest heavily in their businesses in order to continue innovating or strengthening their positions within their industries. The companies tend to argue that they could pull back on reinvestment at any moment and send cash flows soaring, but they aim to achieve the aforementioned moat status first.

What might make investors change their minds?

1. Rubber meets the road of economic reality: Few disruptors and businesses with strong moats are immune to the profound economic shock of COVID-19. Indeed, many of them have seen earnings expectations sharply downgraded even as their stock prices have recovered and valuations soared. Visa, for example, is up 4% year to date, yet its forecast September 2021 earnings per share estimate has come down 18% since December. As a result, its P/E ratio has jumped 22% this year to a 12-year high. This lofty valuation comes even though Visa’s business has no doubt been impacted by travel restrictions, which depress high-margin cross-border transactions. Many other travel-dependent businesses have experienced profound weakness in their share prices, and the trend begs the question of what lies ahead for Visa.

2. Unprecedented strain on government debt and deficit dynamics triggers currency debasement: According to the Congressional Budget Office, the US budget deficit is projected to reach 16% of GDP in 2020 as of mid-October. Even assuming a strong economic recovery, the deficit is forecast at 8.6% of GDP in 2021, within range of the previous post-war record deficit of 9.8% in 2009. In the UK, the deficit is projected to hit 15%, and the government debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to soar past 100% in both nations. France, Italy, and Spain also exhibit troubling debt and deficit dynamics that will require the collective support of the euro area as a whole. Japan tops all other developed countries, with the debt-toGDP ratio expected to hit 250% in the coming years. Only the UK has hit these kinds of debt-to-GDP levels in the past – 260% during World War II. These trends suggest to us that we are approaching the point at which only outright currency debasement, rather than productivity enhancements and economic growth, can bring down these ratios. In short, the crisis has severely compromised financial sustainability, and the likelihood of currency volatility and reversals has increased considerably.

We believe a sustained or multi-year depreciation of the US dollar or the Japanese yen would support equities in regions that are cheap compared to the rest of the world — namely, emerging markets and Japan. In emerging markets, the cheaper dollar would boost the value of local currencies and inflate (USD priced) commodity prices. This improved local currency stability could then encourage foreign direct investment into emerging market countries. In Japan, a cheaper yen would help exporters such as industrial and mining companies, which are exceptionally unloved by the market. It would also likely raise longer-term inflation expectations, which would increase net interest margins for financial companies (given the steepening yield curves). With record low net interest margins and P/B ratios, Japanese banks would be sensitive to a shift in investor expectations on this front.

3. Inflation boosts commodity prices: Mining and energy companies are a key component of the value investment complex and fit the textbook definition of a value company: The outlook for their capital-intensive businesses largely depends on exogenous macro factors that affect the performance of the underlying mixture of commodities they extract and sell. During this period of extended value underperformance, commodity price inflation has been absent or even declining. In many areas, particularly oil and gas, economic growth concerns have been a headwind for a number of years while supply growth has been strong. However, commodity price inflation was evident in the aftermath of the financial crisis, when easy monetary policy weakened the US dollar. As discussed above, the aggressive monetary and fiscal easing in the US recently might not only support commodity prices but prompt sustained inflation as aggressive currency debasement takes place. Should that happen, extractive industries could have a dramatic turnaround. The price of precious metals such as gold has already started to rise, and that increase could feed through to more economically sensitive industrial commodities. One potential caveat: In the longer term, supply disruptions may take place as nation-states encourage miners to decarbonise their businesses— further exacerbating inflationary pressures.

4. Government intervention rains on the parade: Value sectors are typically well established, highly commoditised, and heavily regulated, but growth segments are constantly changing and consolidating by nature. Their relationships with the governments of countries in which they operate are not as well-formed as that of value sectors, and they can run into conflicts with sovereign states that try to ensure that they do not turn into monopolies as they gobble up market share or abuse regulatory and tax regimes. The actual changes that governments demand of these up-and-coming businesses are hugely sensitive to the degree of social and economic stress in a country and the amount of pressure from constituents to act on perceived excesses of power, special treatment, and “rule-bending”. While it is unpredictable, the threat of taxation, antitrust, and regulatory action on newer growth segments of the economy is real.

5. We don’t know what we don’t know: It is worth mentioning again that growth companies and industries tend to be relatively new compared to value companies and industries, without the same experience of navigating through changing economic conditions. The potential catalysts we have outlined here would in most cases initially affect only a subset of value or growth stocks. But such catalysts typically create a waterfall effect and end up boosting the performance of value assets globally, especially given how deeply entrenched the shift from value to growth assets has become at this point. Ultimately, the valuation multiple that any given stock trades on is in part determined by market sentiment, momentum trading flows, behavioural biases, and highly uncertain expectations about future cash flow expectations. Thus, any change to the thesis that underlies investors’ views can be enough to trigger substantial de-ratings or re-ratings, even if the overall outlook for a given business does not change much at first.

What will the value premium look like when it returns?

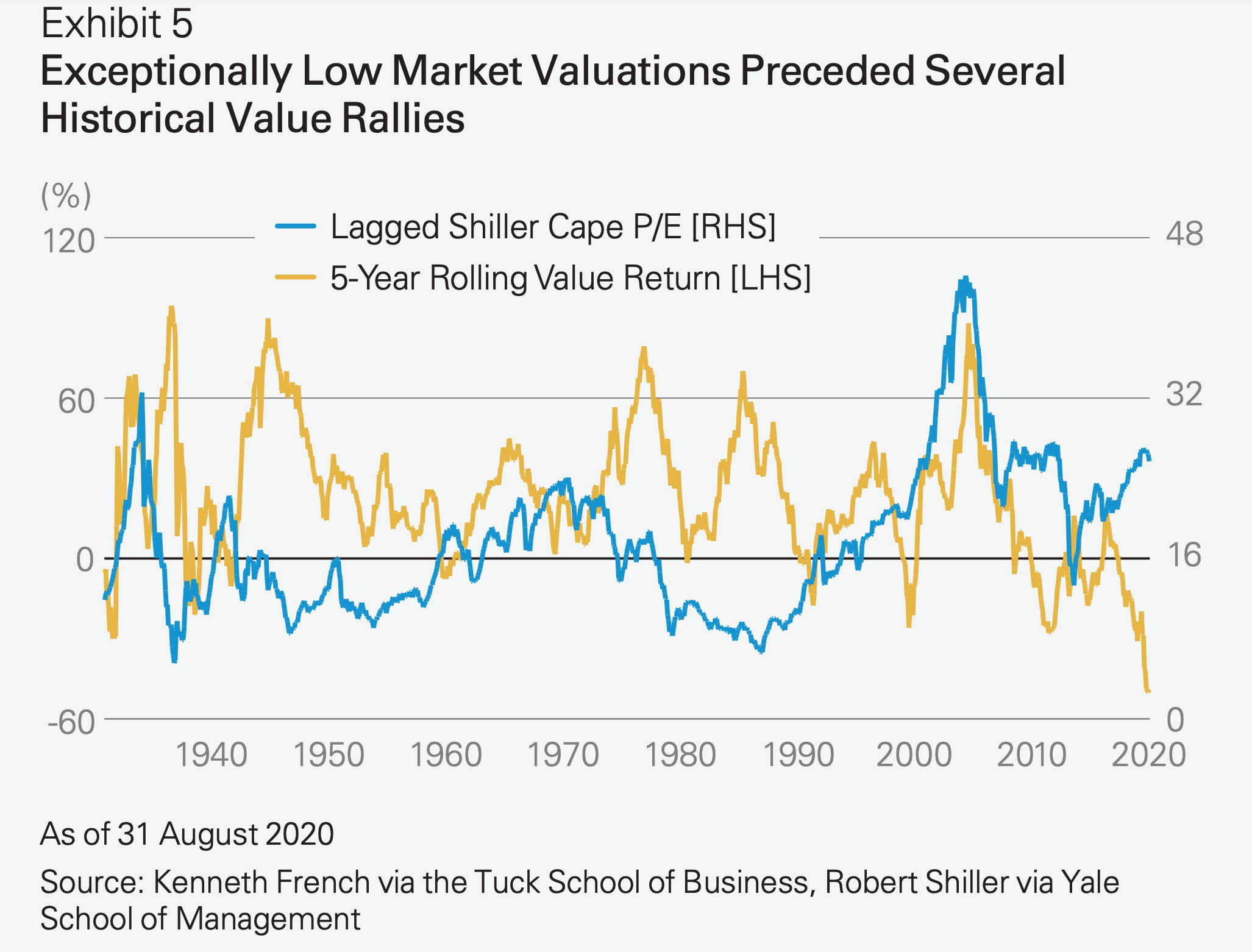

When a growth market has shifted to value in the past, it has often done so quite suddenly. When we compared the rolling five-year performance of low price-to-book (P/B) stocks and high P/B stocks in the US, we found that the outperformance of value stocks has sometimes been explosive.

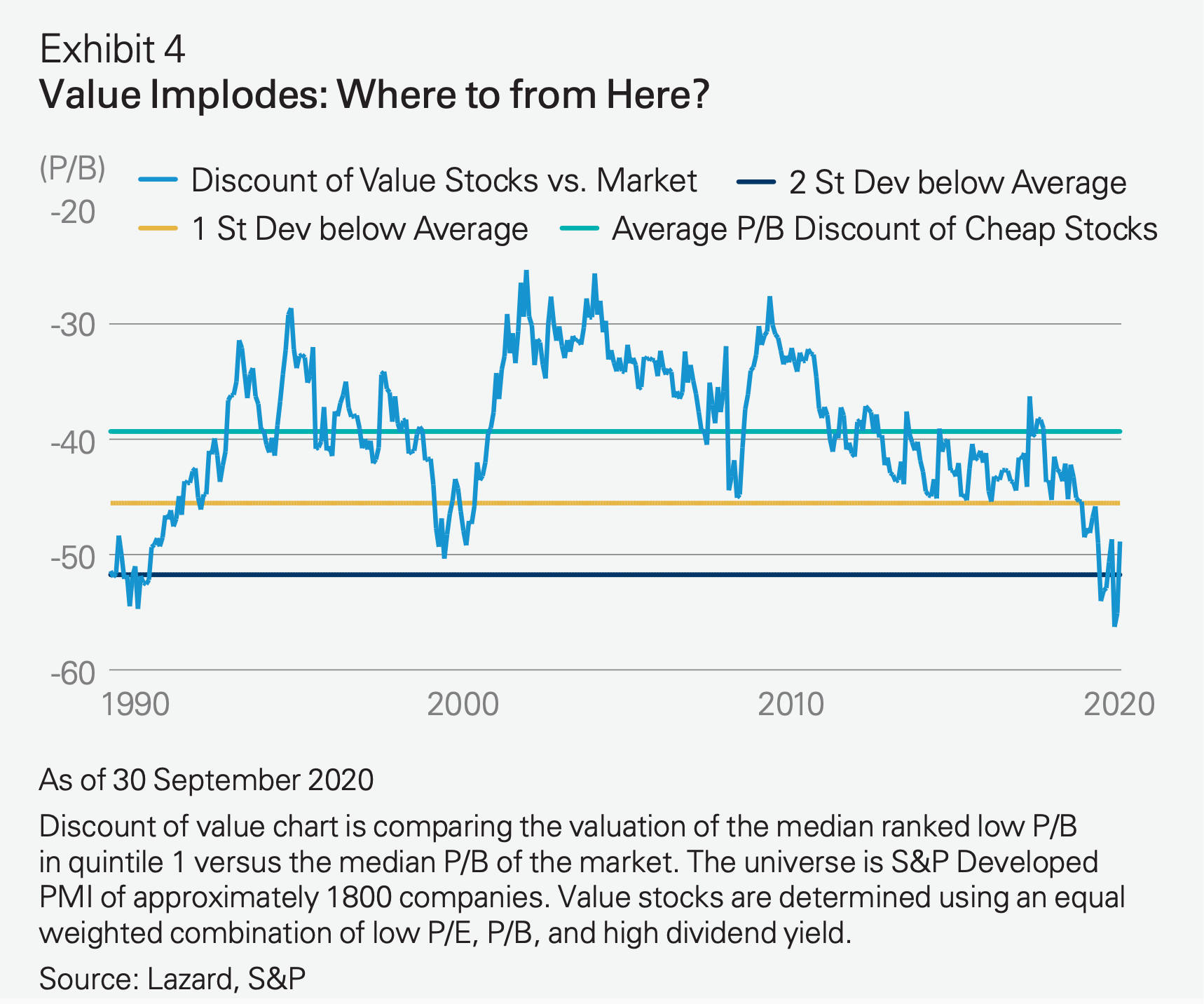

We then attempted to find out why. By comparing the rolling 5-year performance to the 5-year lagged Shiller cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (Exhibit 5), we found that one of two conditions existed before the most explosive value rallies. Either the overall market was trading at exceptionally low cyclically adjusted valuations, as in 1932, 1940, and 1980, or a significant polarisation had opened between growth and value stocks, as in the Nifty Fifty period of the late 1960s or the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s. In each of these five instances, investors had written off value stocks as casualties either of desperately weak economies or as “old economy” stocks doomed to fail in a new economic paradigm, only to see them defy expectations. Today, we have a combination of both characteristics. Value stocks are pricing in an extremely weak economic outlook, and the continued strong performance of growth stocks in a few disruptive sectors, such as technology, are holding up the overall market.

The enormous returns to value have tended historically to manifest in three phases: investors benefit from base effects due to the low price of a stock, profits recover, and the stock re-rates. It is instructive to examine how this process works in one individual stock to start. As we’ve already mentioned, we believe investors must be willing to continue adding capital when short-term price movements go against them in order to benefit from the value premium. Adding capital into short-term weakness can improve the average price of the investment and put investors in a position to take advantage of the base effect of a low price–the supercharged return that occurs when headwinds subside, and a very low valuation begins to unwind. Next comes the previously unthinkable development: an improvement in the profitability outlook for a company. When that happens, a market that has grown accustomed to disappointment suddenly receives a report that earnings will be “better than expected.” Analysts upgrade their outlooks to align with the improved valuation. After the initial solid earnings report, the company goes on to report earnings that are either much more consistent or that beat expectations again, in which case the valuation improves further.

During the five periods of large historic value returns, all three developments in this sequence occurred for a large number of stocks. Regardless of one’s view on the outlook for the value premium, the unusually depressed prices for value securities have the makings for substantial returns in the years ahead.

Conclusion: The role of active investing

There has been an enormous shift in how our equity markets are composed and weighted, and perhaps that shift is a fair reflection of how economic structures have changed. But in the past, when the pace of such shifts has accelerated as they have since 2018, dramatic reversals in which value assets enjoy extraordinary outperformance have typically followed.

Today’s growth concentration at the top of widely followed indices – the top 10 stocks comprise 31.8% of the index in emerging markets and 18% of the index in developed as of mid-October – raise the risk that investors could be disappointed with the equity risk premium they ultimately receive should the boat tip back the other way.

If the stocks that are carrying today’s market fall into a sustained slump, it could hamstring the equity risk premium for years to come. We believe active investment is one of the few ways to not only manage the risks associated with tectonic market shifts, but also to be reactive as events unfold and ensure index risks don’t manifest themselves in performance.

Click the following link to read the full whitepaper on which this article is based, Can investors still believe in the value premium?

Stay informed

For further insights from Lazard Asset Management please visit our website

3 topics

1 contributor mentioned

.png)

.png)