7 lasting impacts from the COVID pandemic

It’s four years since the COVID lockdowns started. The pandemic ended when it morphed into the less deadly Omicron variant in late 2021, but just as a sound can reverberate around a room the effects of the pandemic continue to reverberate in economies. Putting aside the long-term health impacts this note looks at 7 key lasting economic impacts.

#1 Bigger government and more public debt

Memories of the problems of high government intervention in the 1970s have faded and there is rising support for the view that government is the solution to most problems – via regulation, taxes, spending or education campaigns.

The pandemic added to support for “bigger” government: by showcasing the power of government to protect households and businesses from shocks; enhancing perceptions of inequality; and adding support to the view that governments should ensure supply chains by bringing production back home. It’s combining with a desire for governments to pick & subsidise clean energy “winners”.

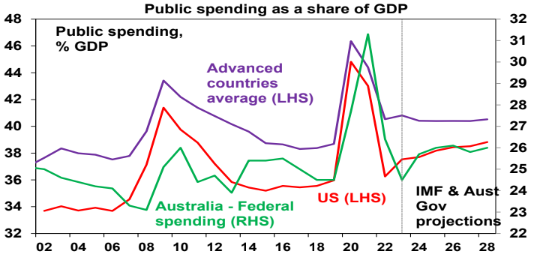

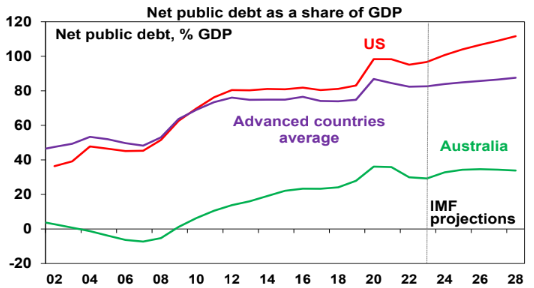

The pandemic ushered in even bigger public debt just as the GFC did. While high inflation helped lower debt to GDP ratios in 2022 it’s settling at higher levels than pre-pandemic.

Meanwhile, higher public debt means: less flexibility to respond with fiscal stimulus to a crisis; a greater incentive for politicians to inflate their way out; and interest payments being a high share of tax revenue.

#2 Tighter labour markets and faster wages growth

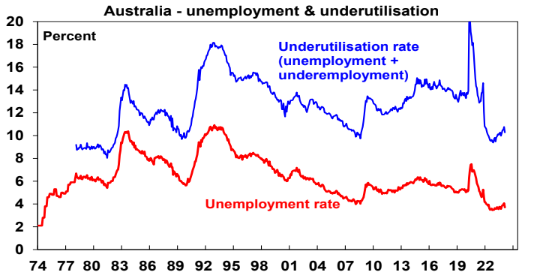

After the pandemic, labour markets have tightened reflecting the rebound in demand post pandemic, lower participation rates in some countries and a degree of labour hoarding as labour shortages made companies reluctant to let workers go.

As a result, wages growth increased, possibly breaking the pre-pandemic malaise of weak wages growth.

Implications – Tighter labour markets run the risk that wages growth exceeds levels consistent with 2 to 3% inflation.

#3 Reduced globalisation/more geopolitical tensions

The pandemic inflamed both: with supply side disruptions adding to pressure for the onshoring of production; conflict over the source of and management of coronavirus; it heightened tensions between the west and China; and it appears to have added to nationalism and populism.

So, the days of global free trade agreements and falling defence spending seem long gone for now. Rather we are seeing more protectionism (eg with subsidies and regulation favouring local production) and increased defence spending.

Implications – Reduced globalisation risks leading to reduced potential economic growth for the emerging world and reduced productivity if supply chains are managed on other than economic grounds. And combined with increased geopolitical tensions resulting in more defence spending it could result in a more inflation prone world than was the case.

#4 Higher prices, inflation and interest rates

Inflation is now starting to come under control as the monetary easing and spending boost has been reversed and supply has improved again but the pandemic has likely ushered in a more inflation prone world by: boosting “bigger” government; adding to a reversal in globalisation; and adding to geopolitical tensions. All of which combine with aging populations to potentially result in more inflation.

Implications – Higher inflation than seen pre-pandemic means higher than otherwise interest rates over the medium term which reduces the upside potential for growth assets like shares and property.

#5 Worse housing affordability

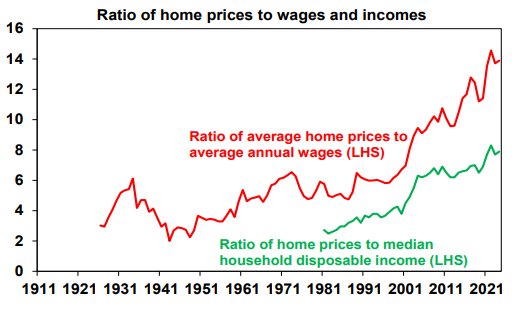

What’s more the lockdowns and working from home drove increased demand for houses over units and interest in smaller cities and regional locations. As a result, Australian home prices surged to record levels. Meanwhile the impact of higher interest rates in the last two years on home prices was swamped by housing shortages as immigration surged in a catch up.

The end result is now record low levels of housing affordability for buyers(who are hit by a double whammy of higher prices relative to incomes-see the next chart - and higher mortgages rates) and renters(who have seen surging rents).

#6 Working from home likely here to stay

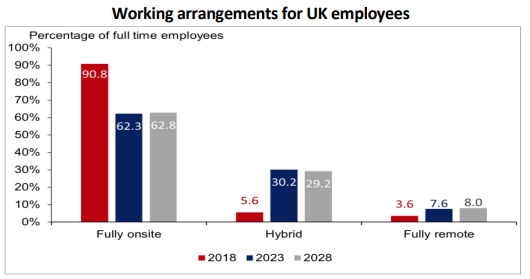

A UK study of over 2000 firms is indicative. It showed that while around 90.8% of employees were fully onsite in 2018, last year this had fallen to 62.3%, with 30.2% with hybrid (working in the office and at home) arrangements. Similarly, the ABS found 37% of employed people in Australia regularly worked from home.

Of course, this masks a huge range with industries with a high proportion of computer-based workers having more hours working at home. And firms expect this to remain the case. There are huge benefits to physically working together around culture, collaboration, idea generation and learning but there are also benefits to working from home with no commute time, greater focus, less damage to the environment, better life balance and for companies - lower costs, more diverse workforces and happier staff.

So the ideal is probably a hybrid model. The proportion of workers in a hybrid model may even rise as new firms are quicker to embrace WFH.

#7 Faster embrace of technology

It may be argued that this fuller embrace of technology will enable the full productivity enhancing potential of technology to be unleased. The rapid adoption of AI will likely help.

Concluding comments

So, a return to pre-pandemic ultra-low inflation and interest rates looks unlikely. It’s not all negative though – apart from the faster technology uptake, the global and Australian economies have come through the last four years in far better shape than might have been imagined at the start of the lockdowns!

2 topics