7 pieces of wisdom from the 2017 Berkshire letter

The latest Buffett letter was released over the weekend. At 17 pages, it was shorter than we’ve become used to, but there was no lack of wisdom flowing from the 87-year-old from Omaha. Notably absent from this year’s letter was any discussion of the Wells Fargo debacle. Buffett has a reputation for facing up to his mistakes, and it was somewhat disappointing to see the issue ignored.

1. The folly of leverage

When everything’s going up, the temptation to add leverage to a portfolio can be irresistible for some investors. Here, Buffett warns investors not to be “handicapped by debt.”

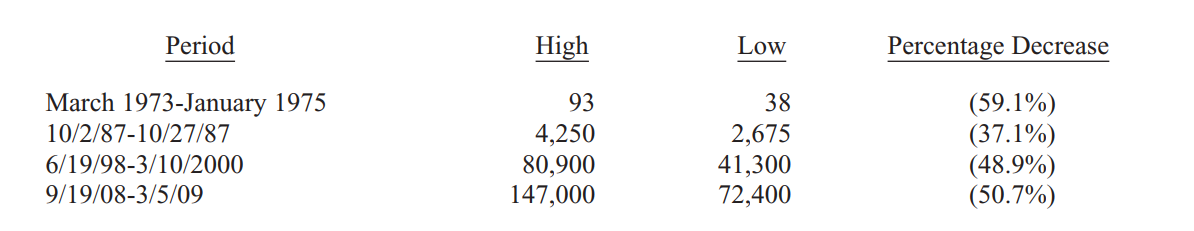

Berkshire, itself, provides some vivid examples of how price randomness in the short term can obscure longterm growth in value. For the last 53 years, the company has built value by reinvesting its earnings and letting compound interest work its magic. Year by year, we have moved forward. Yet Berkshire shares have suffered four truly major dips. Here are the gory details:

This table offers the strongest argument I can muster against ever using borrowed money to own stocks. There is simply no telling how far stocks can fall in a short period. Even if your borrowings are small and your positions aren’t immediately threatened by the plunging market, your mind may well become rattled by scary headlines and breathless commentary. And an unsettled mind will not make good decisions.

In the next 53 years our shares (and others) will experience declines resembling those in the table. No one can tell you when these will happen. The light can at any time go from green to red without pausing at yellow. When major declines occur, however, they offer extraordinary opportunities to those who are not handicapped by debt.

2. Understanding risk

In financial markets, risk is often equated with volatility. For those with a short timeframe this can be true, but here Buffett makes the case that bonds can be risky over the longterm if they fail to meet an investor’s objective.

Investing is an activity in which consumption today is foregone in an attempt to allow greater consumption at a later date. “Risk” is the possibility that this objective won’t be attained.

By that standard, purportedly “risk-free” long-term bonds in 2012 were a far riskier investment than a longterm investment in common stocks. At that time, even a 1% annual rate of inflation between 2012 and 2017 would have decreased the purchasing-power of the government bond that Protégé and I sold.

I want to quickly acknowledge that in any upcoming day, week or even year, stocks will be riskier – far riskier – than short-term U.S. bonds. As an investor’s investment horizon lengthens, however, a diversified portfolio of U.S. equities becomes progressively less risky than bonds, assuming that the stocks are purchased at a sensible multiple of earnings relative to then-prevailing interest rates.

It is a terrible mistake for investors with long-term horizons – among them, pension funds, college endowments and savings-minded individuals – to measure their investment “risk” by their portfolio’s ratio of bonds to stocks. Often, high-grade bonds in an investment portfolio increase its risk.

3. Why CEOs are like teenagers

With so much cash on corporate balance sheets in America, this warning from Buffett on the dangers of acquisition-hungry CEOs will probably prove timely in hindsight. I’ll let his analogy speak for itself…

If Wall Street analysts or board members urge that brand of CEO to consider possible acquisitions, it’s a bit like telling your ripening teenager to be sure to have a normal sex life. Once a CEO hungers for a deal, he or she will never lack for forecasts that justify the purchase. Subordinates will be cheering, envisioning enlarged domains and the compensation levels that typically increase with corporate size. Investment bankers, smelling huge fees, will be applauding as well. (Don’t ask the barber whether you need a haircut.) If the historical performance of the target falls short of validating its acquisition, large “synergies” will be forecast. Spreadsheets never disappoint.

4. Be prepared to look foolish

Investing is an intellectual pursuit for many, so the ability to ‘look right’ can be strong. However, successful investing requires being able to bet against the crowd and look foolish sometimes.

Though markets are generally rational, they occasionally do crazy things. Seizing the opportunities then offered does not require great intelligence, a degree in economics or a familiarity with Wall Street jargon such as alpha and beta. What investors then need instead is an ability to both disregard mob fears or enthusiasms and to focus on a few simple fundamentals. A willingness to look unimaginative for a sustained period – or even to look foolish – is also essential.

5. The attributes of a potential Berkshire acquisition

Buffett-watchers would no doubt have heard these basic principals many times before, but a reminder of the basics never goes astray. Interestingly, Buffett comments on the difficulty of finding reasonably-priced deals speaks to the late stage of the current market cycle.

In our search for new stand-alone businesses, the key qualities we seek are durable competitive strengths; able and high-grade management; good returns on the net tangible assets required to operate the business; opportunities for internal growth at attractive returns; and, finally, a sensible purchase price.

That last requirement proved a barrier to virtually all deals we reviewed in 2017, as prices for decent, but far from spectacular, businesses hit an all-time high. Indeed, price seemed almost irrelevant to an army of optimistic purchasers.

6. Another point on leverage

Buffett alludes to the ‘sleep test’ for investing here, but the part in bold really stood out to me. In the decades to come, I suspect this quote will be repeated often.

Our aversion to leverage has dampened our returns over the years. But Charlie and I sleep well. Both of us believe it is insane to risk what you have and need in order to obtain what you don’t need. We held this view 50 years ago when we each ran an investment partnership, funded by a few friends and relatives who trusted us. We also hold it today after a million or so “partners” have joined us at Berkshire.

7. Keep it simple

If it’s not leverage tempting investors into mistakes, the other culprit is activity. A simple decision by Buffett and Protégé (the firm with whom he made his million dollar bet) in 2012, means than Buffett’s chosen charity will now receive $2,222,279 instead of the original million.

A final lesson from our bet: Stick with big, “easy” decisions and eschew activity. During the ten-year bet, the 200-plus hedge-fund managers that were involved almost certainly made tens of thousands of buy and sell decisions. Most of those managers undoubtedly thought hard about their decisions, each of which they believed would prove advantageous. In the process of investing, they studied 10-Ks, interviewed managements, read trade journals and conferred with Wall Street analysts.

Protégé and I, meanwhile, leaning neither on research, insights nor brilliance, made only one investment decision during the ten years. We simply decided to sell our bond investment at a price of more than 100 times earnings (95.7 sale price/.88 yield), those being “earnings” that could not increase during the ensuing five years.

We made the sale in order to move our money into a single security – Berkshire – that, in turn, owned a diversified group of solid businesses. Fuelled by retained earnings, Berkshire’s growth in value was unlikely to be less than 8% annually, even if we were to experience a so-so economy.

After that kindergarten-like analysis, Protégé and I made the switch and relaxed, confident that, over time, 8% was certain to beat .88%. By a lot

3 topics