9 bad habits of ineffective investors: Common mistakes investors make

Mistake #1: Crowd support indicates a sure thing

“I will tell you how to become rich...Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.” Warren Buffett, investor and CEO

It’s normal to feel safer investing in an asset when your friends and neighbours are doing the same and media commentary is reinforcing the message that it’s the place to be. But “safety in numbers” is often doomed to failure. The trouble is that when everyone is bullish and has bought into an investment with general euphoria about it, it gets to a point where there is no one left to buy in the face of more positive supporting news but instead, there are lots of people who can sell if the news turns sour.

Of course, the opposite applies when everyone is pessimistic and bearish and has sold – it only takes a bit of good news to turn the value of the asset back up. So, the point of maximum opportunity is when the crowd is pessimistic (or fearful) and the point of maximum risk is when the crowd is euphoric (and greedy).

Mistake #2 Current returns are a guide to the future

“Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.” - Standard disclaimer

Faced with lots of information, investors often use simplifying assumptions, or rules, in order to process it. A common one of these is that “recent returns or the current state of the economy and investment markets are a guide to the future.” So tough economic conditions and recent poor returns are expected to continue and vice versa for good returns and good economic conditions.

The problem with this is that when it’s combined with the "safety in numbers" mistake, it results in investors getting in at the wrong time (e.g. after an asset has already had strong gains) or getting out at the wrong time (e.g. when it is bottoming). In other words, buying high and selling low.

Unfortunately, we have heard the “this time is different” argument many times before only to find out that it’s not – usually when we are most complacent! The reality is that shares have done well over the last two years because they came off a big cyclical fall in 2022 and the threats have not proved that serious economically.

For instance, the much-feared recession has failed to appear and the war in the Middle East has not disrupted global oil supplies (so far). the “central bank put” did not prevent the tech wreck & the GFC (both saw US shares fall around 50%) and various other share market plunges. Just because shares have had strong returns over the last two years - despite lots of worries - doesn’t mean that the cycle has been abolished and that there is nothing at all to worry about.

Mistake #3 “Experts” will tell you what will happen

“Economists put decimal points in their forecasts to show that they have a sense of humour.” William Gillmore Simms, novelist and politician

No one has a perfect crystal ball. Forecasts as to where the share market, property market, and currencies will be at a particular time have a dismal track record, so they need to be treated with care. Usually, the grander the forecast—calls for "new eras of permanent prosperity" or for "great crashes ahead"—the greater the need for scepticism as either they get the timing wrong or it’s dead wrong.

Market prognosticators suffer from the same psychological biases as everyone else. And sometimes forecasts themselves can set in motion policy changes that make sure they don’t happen – such as rate cuts heading off sharp house price falls in the pandemic in 2020. The key value of investment experts is to provide an understanding of the issues around investment and to put things in context. This can provide valuable information regarding understanding the potential for an investment. But if forecasting was so easy, the forecasters would be rich and so would have retired!

Mistake #4 Shares can’t go up in a recession...

“It’s so good it’s bad, it’s so bad it’s good.” Anon

Of course, shares kept rising into 2022, economies recovered, and earnings rebounded. The reality is that share markets are forward-looking, so when economic data and profits are really weak, the market has already factored it in. History tells us that the best gains in stocks are usually made when the economic news is still poor, as stocks rebound from being undervalued and unloved, helped by falling interest rates. In other words, things are so bad they are good for investors!

Of course, the opposite applies at market tops after a sustained economic recovery has left the economy overheated with no spare capacity and rising inflation. The share market frets about rising rates. Hence things are so good they become bad! This seemingly perverse logic often trips up many investors.

Mistake #5 Letting a strongly held view get in the way

“The aim is to make money, not to be right.” Ned Davis, investment analyst

This is easy to do as the human brain is wired to focus on the downside more than the upside, so we are easily attracted to doomsayers. They could be right one day but lose a lot of money in the interim. Giving too much attention to pessimists doesn’t pay for investors.

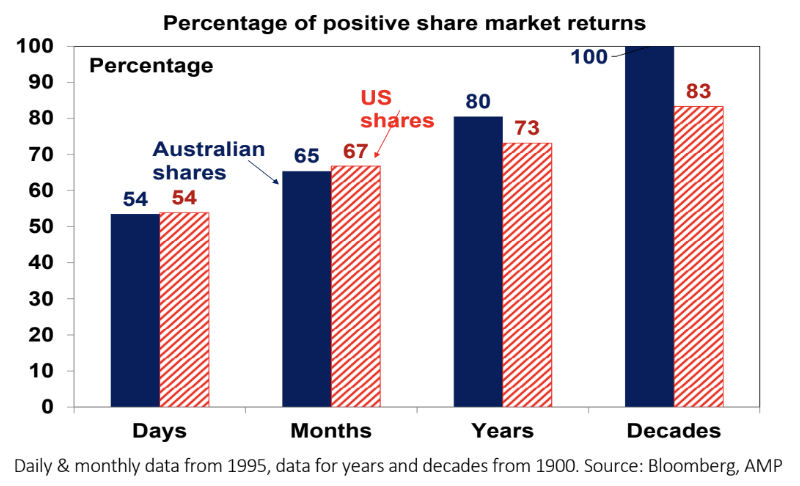

Mistake #6 Looking at your investments too much

“Investing should be like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement...go to Las Vegas.” Paul Samuelson, economist

Mistake #7 Making investing too complex

“There seems to be a perverse human characteristic that makes easy things difficult.” Warren Buffett

You can spend so much time focussing on this stock or ETF versus that stock or ETF or this fund manager versus that fund manager that you ignore the key driver of your portfolio’s risk and return, which is how much you have in shares, bonds, real assets, cash, onshore versus offshore, etc.

Or that you end up in things you don’t understand. Instead, it’s best to avoid the clutter, don’t fret about the small stuff, keep it simple and don’t invest in things you don’t understand.

Mistake #8 Too conservative early in life

“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it...he who doesn’t, pays it.” Albert Einstein, theoretical physicist

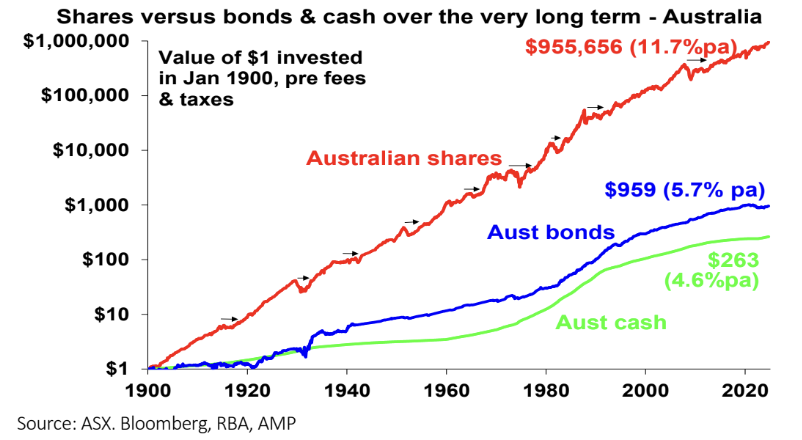

Despite periodic setbacks, shown with arrows (such as WWI, the Great Depression, WWII, stagflation in the 1970s, the 1987 share crash and the GFC), shares and other growth assets grow to much higher values over time thanks to their higher returns over the long term than cash and bonds and thanks to the magic of compound interest where higher returns build on higher returns through time.

Not having enough growth assets early in their career can be a problem for investors as it can make it harder to adequately fund retirement later in life as they miss out on the magic of compounding higher returns on higher returns through time in growth assets like shares and property.

Fortunately, compulsory superannuation in Australia helps manage this - although early super withdrawal for various purposes (through the pandemic, for medical needs and as proposed for housing) may set this back for some.

For example, a 30-year-old who withdraws $20,000 from their super could have around $184,000 (or $74,000 in today’s dollars) less when they retire at age 67 based on assumptions in the ASIC MoneySmart Super Calculator.

Mistake #9 Trying to time the market

“Far more money has been lost by investors in preparing for corrections, or anticipating corrections, than has been lost in the corrections themselves.” - Peter Lynch, fund manager

Perhaps the best example of this is a comparison of returns if the investor is fully invested in shares versus missing out on the best days. Of course, if you can avoid the worst days during a given period you will boost your returns.

The last two years provide a classic example of how hard it is to time markets – there has been a long worry list, so it’s been easy to be gloomy but the timing markets on the back of this has been a loser as shares put in strong gains.

2 topics