A refresher on mortgage-backed securities

Global markets continue to feel the aftershock of the regional banking crisis in the US – we imagine the words “Credit Suisse”, “uninsured deposits” and “bank runs” are now permanently echoing in the mind of any banking analyst across the globe after a week of intense questioning.

Understandably (albeit not necessarily ‘accurately’), the spectre of the GFC lingers in the minds of many investors when news of banks going bust starts to surface. One freshly turned gravestone of financial history is that of Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS).

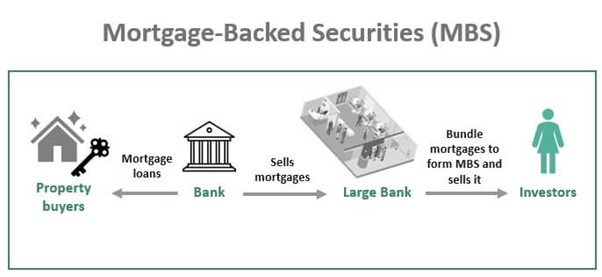

A MBS is a basket of underlying loans, specifically home loans (mortgages), which are purchased from issuing banks and packaged into a more liquid product that provides coupon payments – much like a corporate bond. This note will take a distinctly US focus, given the recent financial turmoil across the Pacific.

In reality, the ‘large bank’ noted in that diagram is most commonly semi-government agencies such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, where these institutions have mandates to purchase residential mortgages and create financial products.

It is important to note here that MBS securities are NOT the infamous CDOs (or Collateralised Debt Obligations), which of course made headlines during the GFC of 2008. Whilst the structure is similar, the difference is in the quality of the loans.

MBS loans are generally NOT delinquent mortgages, whilst CDOs were offered out to those who can’t afford a mortgage with no down payment, packaged up with unrealistic credit ratings. The vast majority of the underlyings in MBS are loans with a capital downpayment, lent out to individuals who pass a credit check – and those loans that might be higher risk sit in a higher risk bucket and pay more interest to compensate that risk, but the predatory lending practices that led up to the financial crises are not the mainstay of the MBS market.

In addition, credit ratings agencies have a lot more experience in this area and a track record of assigning pretty accurate credit ratings to the instruments. This is unlike in the GFC when they didn’t know what they were rating, and even the most highly rated assets were in fact delinquent loans, just loans that got paid out first if anything went wrong.

Why own MBS?

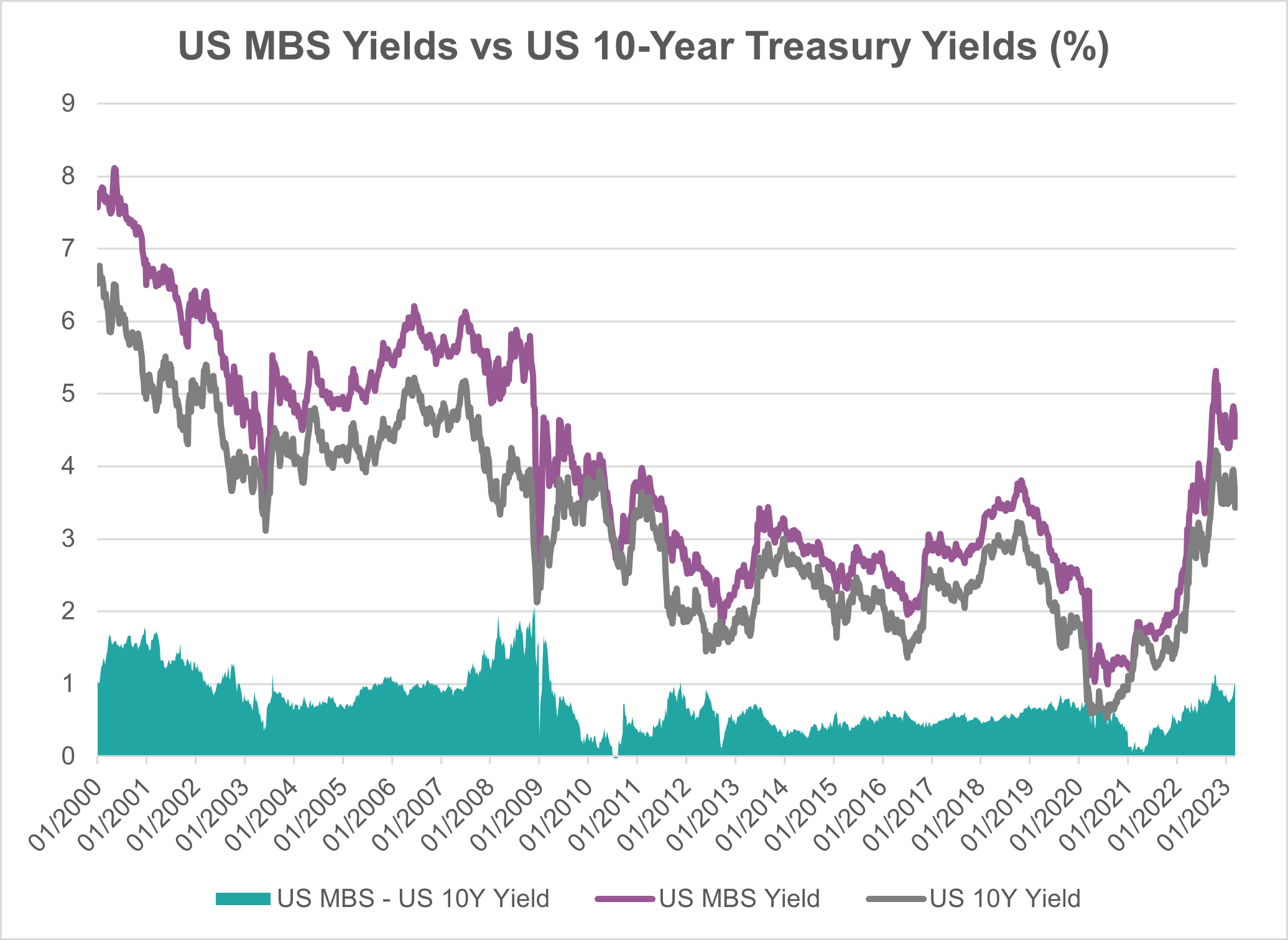

The yield on US MBS generally has a premium over a risk-free investment, such as AAA-rated government bonds. This is often measured as a spread over an entire yield curve, and is generally ~0.5% on average. Of course, you can also look at a broad MBS index yield over a single security, such as the 10-Year Treasury Bond yield.

In an era of low interest rates, the higher yield offered by MBS over government bonds was meaningful enough to warrant being staple holdings in many large fixed income portfolios, even if the spread itself was only modest (less than 1%) – when bonds are yielding 3% and above, taking on MBS risk to get ~0.7% more is difficult for a firm to justify, but it becomes easier when government bonds are giving you less than 1% at the outset.

Being such a large asset class – in fact, global property is the largest asset class in the world by total value – it stands to reason that investors would want exposure.

However, single mortgages have three main barriers to being in a portfolio:

1. Size: the average mortgage in the US is $430k USD (source: Mortgage Bankers Association of America)

2. Concentration/credit risk: a single mortgage relies entirely on the repayment capability/creditworthiness of a single repayor

3. Liquidity: the bulk of US mortgages are fixed rate and out to 30-years in duration, meaning if there is no refinancing or early offset, a purchaser of this mortgage would be locked for 30 years

Packaging mortgages solves all of these issues:

1. As of 06/03/2023, over $180 billion USD of MBS had been issued in the US, and over $250 billion USD had been traded in the agency market

2. MBS tranches will generally contain over 1,000 loans, diversifying the individual household credit risk across a wide variety of borrowers

3. The MBS market is liquid and involves some of the largest financial institutions in the world (including the Federal Reserve), meaning a motivated buyer or seller could almost always find volume where they need it (at what price is another question)

What are the issues with MBS today?

Despite having numerous advantages, MBS are not a perfect security – the exposure is certainly not as concerning as 2007-08, however, there are still structural challenges to this security which contributed in part to the issues faced by the like of Silicon Valley Bank recently.

We discussed how liquidity risk is minimized by offering MBS into a large and deep market, and how credit risk is managed via a diversified pool of loans.

Anybody who is familiar with fixed income may now be asking, “so what about the interest rate risk?”. This is a good question, and apparently not one that executives of SIVB were asking themselves the past year.

If you locked in a mortgage at 5% for 30 years in 2021 – well firstly, well done on nailing down that kind of rate as we Australians stare down the barrel of 7% floating rate mortgages – but more importantly, if mortgage rates fell to 3% in 2023, you would, of course, refinance at this lower rate.

That means that if rates go down, then the mortgages inside RMBS get repaid early, and these rates begin to act more cash-like since the borrowers are repaying their obligations early and taking out new loans outside of the MBS structure you are currently invested into. So, very little upside from falling rates.

And if rates rise? Well, much like any long-duration (interest rate sensitive) asset, the price will fall – in some cases to an aggressive extent, another problem SIVB found themselves faced with recently.

To clarify, this is because US mortgages are largely fixed-rate over many years. This is less the case in Australia, where our mortgages are floating rate with fixed rate terms generally only being up to 5 years, which means Aussie RMBS participate in upside from rate rises.

So what banks, institutions and investors are left holding is a security that is asymmetrically exposed to interest rate risk. We regularly discuss in our pieces the merit of finding asymmetric opportunities, but in that case, we’re implicitly looking for positive opportunities, where MBS in this case is negative: you lose if rates rise, and you don’t get to participate in the upside if rates fall – as mentioned this is less of a risk with Aussie mortgages, particularly when you can get exposure at attractive prices and with reputable managers.

Balancing the Books

It’s likely that uncertainty, and volatility, around financial crisis fears, will remain high for the near future. No doubt any bank found with concentrated deposit bases, poor interest rate risk management or large asset books of MBS bought more than a year ago will be under intense scrutiny by investors.

Whilst recent events are important macro catalysts, the implications of which are too lengthy and too fast-moving to fit into a 1,000-word note, it sometimes helps to dig into the minutia to understand why something has happened and better comprehend how this could occur in the future. Understanding the driver of volatility is one factor that separates reactive trading from pragmatic investing.

3 topics