Another new puzzle: bank senior spreads vs government bonds

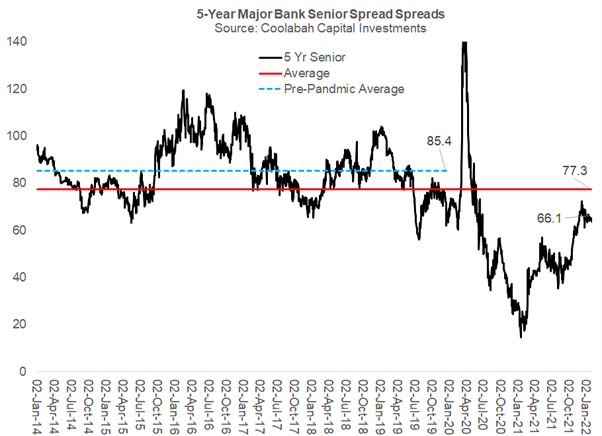

Back in August and September 2021 we noted a very odd anomaly: for the first time, 5-year major bank senior unsecured bond spreads were trading in line with, or at times actually tighter than, more highly rated and liquid 10-year State government bond spreads. We had never seen this before, and forecast that APRA closing the $140 billion Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF), which they subsequently announced, would push 5-year major bank senior bond spreads up from their post-GFC tights of about 25-30 basis points (bps) above BBSW to a more normal range of 70-120bps over BBSW.

As history now records, APRA did indeed announce the closure of the CLF and major bank senior bond spreads duly jumped to 70bps, which is about where they sit right now (technically, we have mids at 66bps). Recall that under the $140 billion CLF, Aussie banks were uniquely allowed to buy one another's senior unsecured paper, thereby putting material downward pressure on their credit spreads. Yet by the end of this year, the banks will no longer be able to use the CLF.

And the numbers were massive: Westpac reported yesterday that their CLF assets, known as "alternative liquid assets", had actually increased (rather than decreased) in the final quarter of 2021 from $33 billion to $37 billion. It seems like the traders at Westpac had been buying a lot of bank bonds at historically very tight spreads! (Note that as at 1 January, these CLF assets will fall to $27.75 billion, and also include internal Westpac loans in addition to bank bonds---with loans making up the majority.)

While these CLF assets currently count in Westpac's Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), which it reported was 142%, stripping them out drops Westpac's LCR to a much lower 116%. Bank boards target LCRs, which are immensely volatile, of at least 125-135%, and the Aussie banking system has historically run an LCR over 130% both prior to, and since, the pandemic. (In late 2020, bank LCRs did jump to much higher levels due to excess liquidity, but they have now mostly normalised.)

Bank senior bond spreads still look very dear...

Turning back to bank credit spreads, our 5-year major bank senior bond index is trading at about 66bps (at mid). This is proving relatively resilient given this spread is 11bps tight of the average 77bps level for 5-year bank senior paper since 2013, noting this "average" includes the post-pandemic period when banks were able to uniquely borrow $188 billion off the RBA and hardly issued any debt, driving spreads to the tightest levels since 2007. If we look at the more normal post-GFC and pre-pandemic period, the average 5-year major bank senior spread jumps to 85bps. That makes the 66bps level today look awfully expensive. And even more so considering that the all-important CLF bid from banks will fade away over 2022...

How do government bond spreads look?

There used to be a linkage between senior bank bond spreads and State government bond spreads created by the CLF. Under the $140 billion CLF, banks could switch their liquid assets from government bonds to bank bonds depending on their relative merits. With the CLF being shut-down in 2022, this fungibility is disappearing. With the exception of Westpac, all the other banks have been winding-down their CLF assets and withdrawing from the CLF-enabled tendency of buying their peers' paper.

APRA has formally instructed the banks to replace their $140 billion CLF with government bonds. So whereas bank bonds are going to lose up to $140 billion of theoretical demand, Commonwealth and State government bonds will replace this interest.

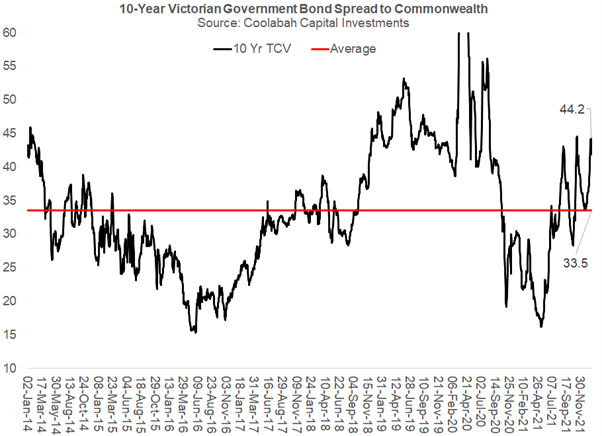

Our analysts' careful modelling suggests that total system-wide bank demand for Aussie government bonds will be about $409 billion over the next three years with a reasonable range from about $280 billion to $550 billion. This is interesting because if we look at 10-year Victorian government bond spreads they are currently trading about 11bps wide, not tight, of their average levels since 2013 (recall bank senior bonds are trading 11bps tight of their averages over the same period). It tends to take for time the market (and even the banks) to figure these anomalies out, as we saw when major bank senior was trading at an absurdly tight 25-30bps over BBSW in early 2021, which was never going to last. Ironically, it was the banks themselves who were the biggest buyers of 5-year senior bonds issued by NAB and Suncorp at ridiculously expensive levels of 41bps and 48bps over BBSW in late 2021, just prior to APRA announcing it would shut the CLF.

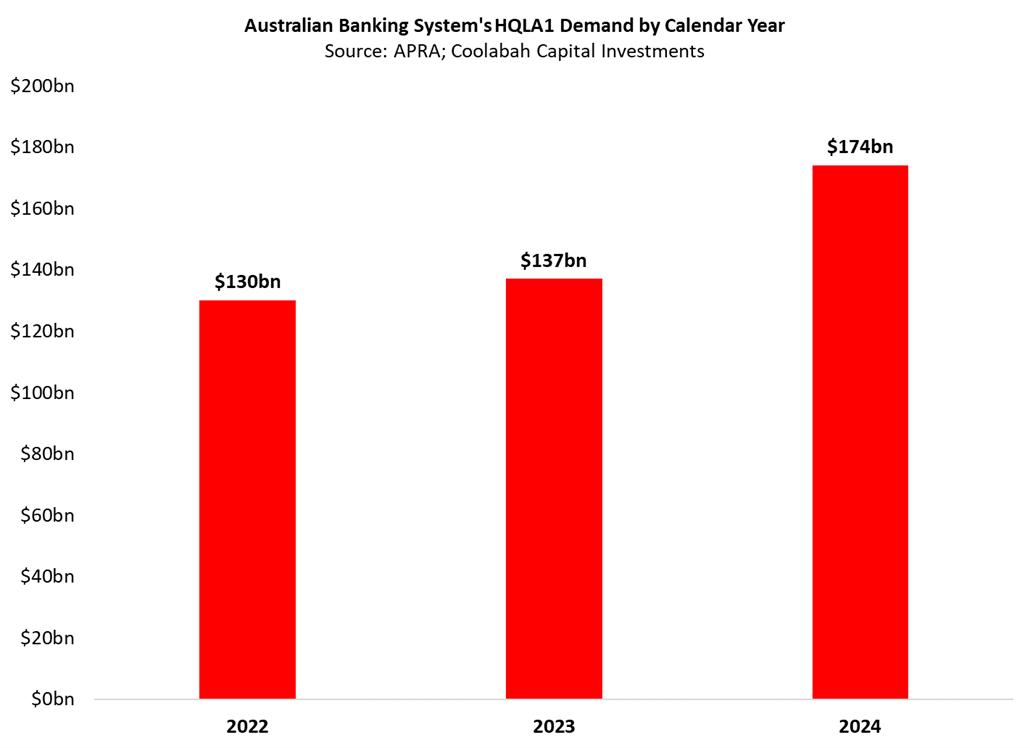

Government bond buying demand averages more than $130bn pa

It is important to understand the totality of bank demand for their so-called "Level 1 high quality liquid assets" (HQLA1), which according to APRA includes Commonwealth and State government bonds, and any cash held on deposit at the RBA.

First, banks have to replace the $140 billion CLF. While Westpac reported yesterday that it had bought $29 billion of extra government bonds in the fourth quarter of 2021, it was still carrying $37 billion of CLF assets as at 31 December that will be removed from its LCR in 2022. And the sharp compression in Westpac's net interest margin, which slumped 6bps just from the impact of liquid assets, indicates the bank may have been caught carrying too much low-margin HQLA1 that does not pay it a positive spread above the swap rate.

Banks also have to hold extra liquid assets as their balance-sheets grow, and they are growing incredibly quickly right now. On our conservative numbers, balance-sheet growth of only 5% pa over the next few years will drive another $100 billion of HQLA1 demand alone. At present, bank balance-sheets are growing at a much faster pace than this, which will necessitate even higher HQLA1 (ie, the increment could be a lot larger than $100 billion).

Banks then lose another $188 billion of HQLA1, which they will have to replace, as they repay the money they borrowed from the RBA under the Term Funding Facility. While some of this money is formally due for repayment in the first half of 2023, banks will likely smooth these repayments over time.

A final factor is the $53 billion of HQLA1 they lose as government bonds mature off the RBA's balance-sheet between now and the end of 2024.

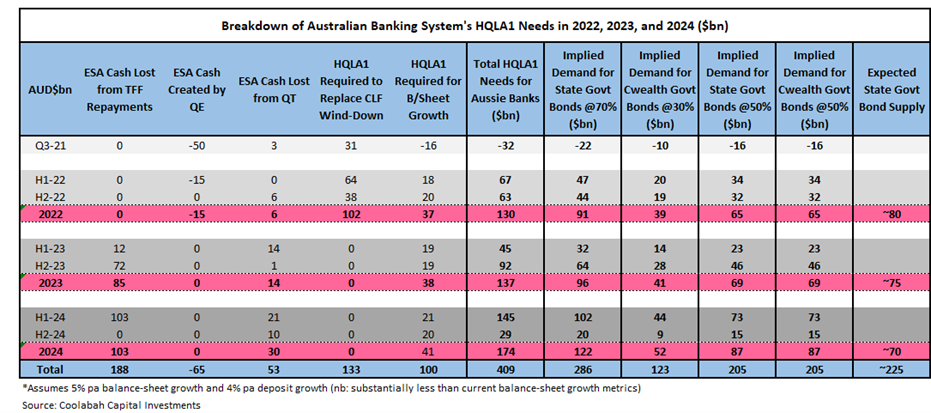

I previously published the following chart breaking down the entire banking system's demand for HQLA1 each year. The table shows the individual drivers of HQLA1 demand contrasted against the annual supply of HQLA1 from State issuers (see the final six columns in the table below).

3 topics