Are you under-invested in bullion? The answer may depend on your definition of risk

In determining the desired outcome from any investment strategy a critical cornerstone to set securely in place is the definition of risk. At first this may appear trivial or academic until one appreciates that the entire approach to implementing an investment strategy will be determined by the concept of risk adopted by the investor. Given this, though historical return volatility in both an absolute and relative sense is a commonly used method for quantifying risk, there is technically no right or wrong answer to what constitutes the appropriate measure of risk. The aim of this paper is to illustrate a different perspective to the definition of risk and highlight how this can impact upon how an investor views the risk hierarchy of assets.

Another Approach to Thinking About Risk

In the process of making investment decisions, particularly in the context of portfolio construction, risk is typically measured as volatility in investment returns. There are sound quantitative reasons for this given that the concept of risk is somewhat nebulous and modern portfolio construction requires formalised measures to provide structure to the process. Furthermore, such an approach to viewing risk could be considered comprehensive if all inherent risk perfectly and consistently manifests as return volatility. But while such a view of risk is convenient with respect to formalising the structure around portfolio construction it must be borne in mind that return volatility is simply acting as a readily observable proxy of the true underlying drivers of risk. As a proxy there are potential limitations such as (a) there may be times when return volatility does not adequately capture the varied aspects of risk and (b) return volatility is of little use in explaining the underlying dynamics which may be impacting on investor risk preferences. To understand the dynamics associated with risk tolerance it is necessary to go beyond return volatility as the measure of risk. This requires a more in-depth consideration of what may drive an investor’s perception of risk.

The lens through which the concept of risk will be viewed is that of trust. Trust is defined many ways but examples of two definitions should suffice to give a flavour of what is meant by the term:

1) Trust (noun): reliance on the integrity, strength, ability, surety etc, of a person or thing

2) Trust (verb): to rely upon or place confidence in someone or something.

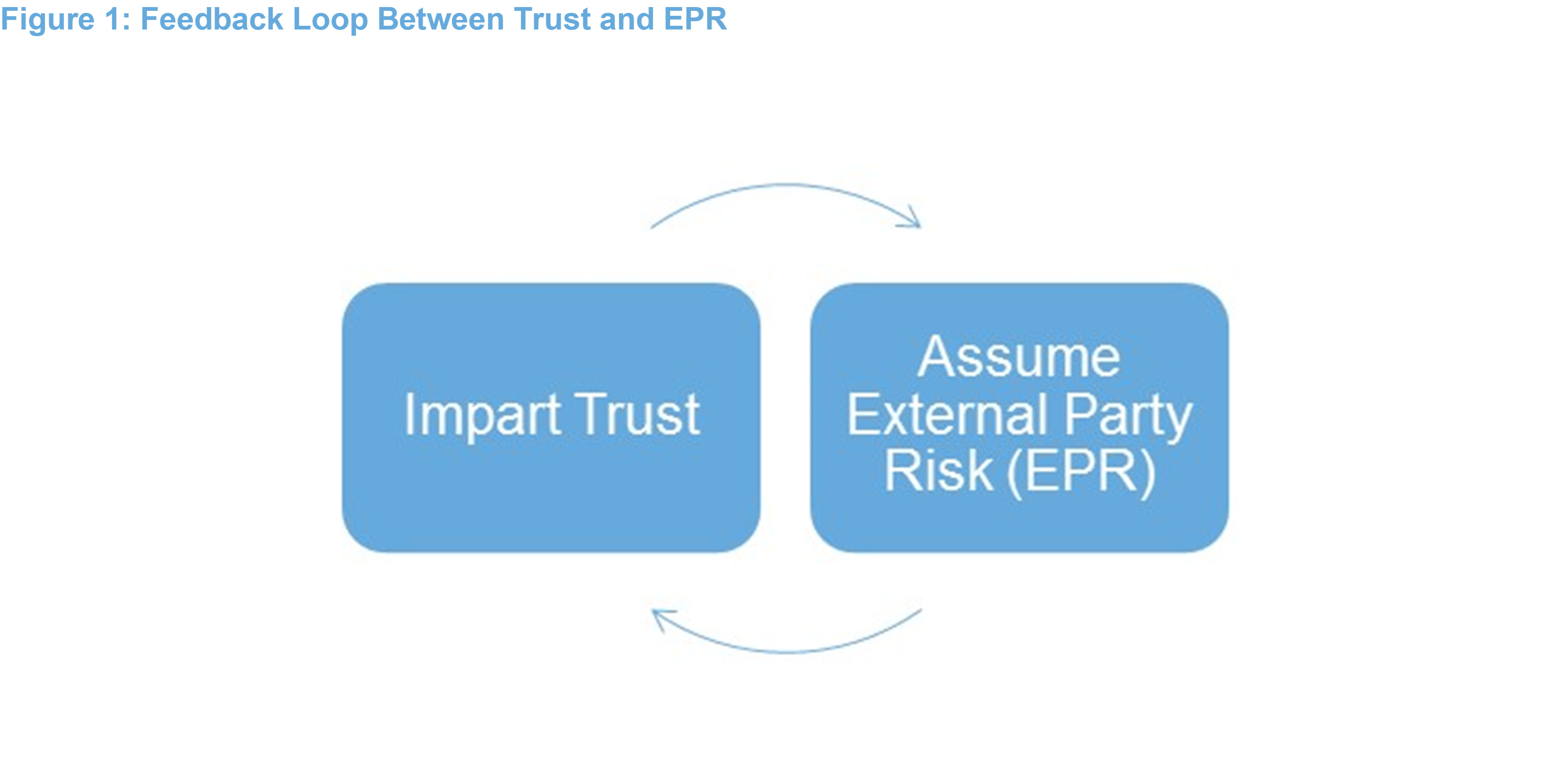

But why is trust so integral to the concept of risk? Trust is important in modern economic/financial systems as much of what we view as assets and liabilities are intangible in nature. Put another way, many assets and liabilities have little tangible/intrinsic value other than the expectation of some future value via promises of future payments or services to be rendered. Just consider what is the intrinsic value of a (a) share certificate, (b) $50 note, or even (c) an internet web page which tells you that the balance in your bank account is say $10,000? When the world is looked at through this lens it can be appreciated that, based upon the nature of the relationship, trust is a requirement in nearly all aspects of economic/financial transactions. As such any financial transaction, other than the instantaneous bartering of homogeneous physical commodities, incorporates the premise that individuals impart trust to external parties and by doing so assume, what this paper terms as, external-party-risk (“EPR”). EPR includes such risks as counterparty risk and agency risk but goes further to include risks associated with actions by external parties not even directly associated with the original financial transaction such as governments etc. Therefore, trust and EPR are simply two sides of the same coin. As an investor imparts more trust, likewise the EPR they assume rises, and vice versa. So not only do differences in the perception of the level of EPR between assets affect their relative attractiveness but so will changes in the perception of EPR for any single asset over time. The result being that the EPR premium (additional return required to assume higher levels of ERP) attached to assets will vary over the cycle with it not being a static concept. In turn the changes in EPR will have an impact on the valuations, both absolute and relative, associated with the different types of assets.

How does EPR relate to different classes of assets?

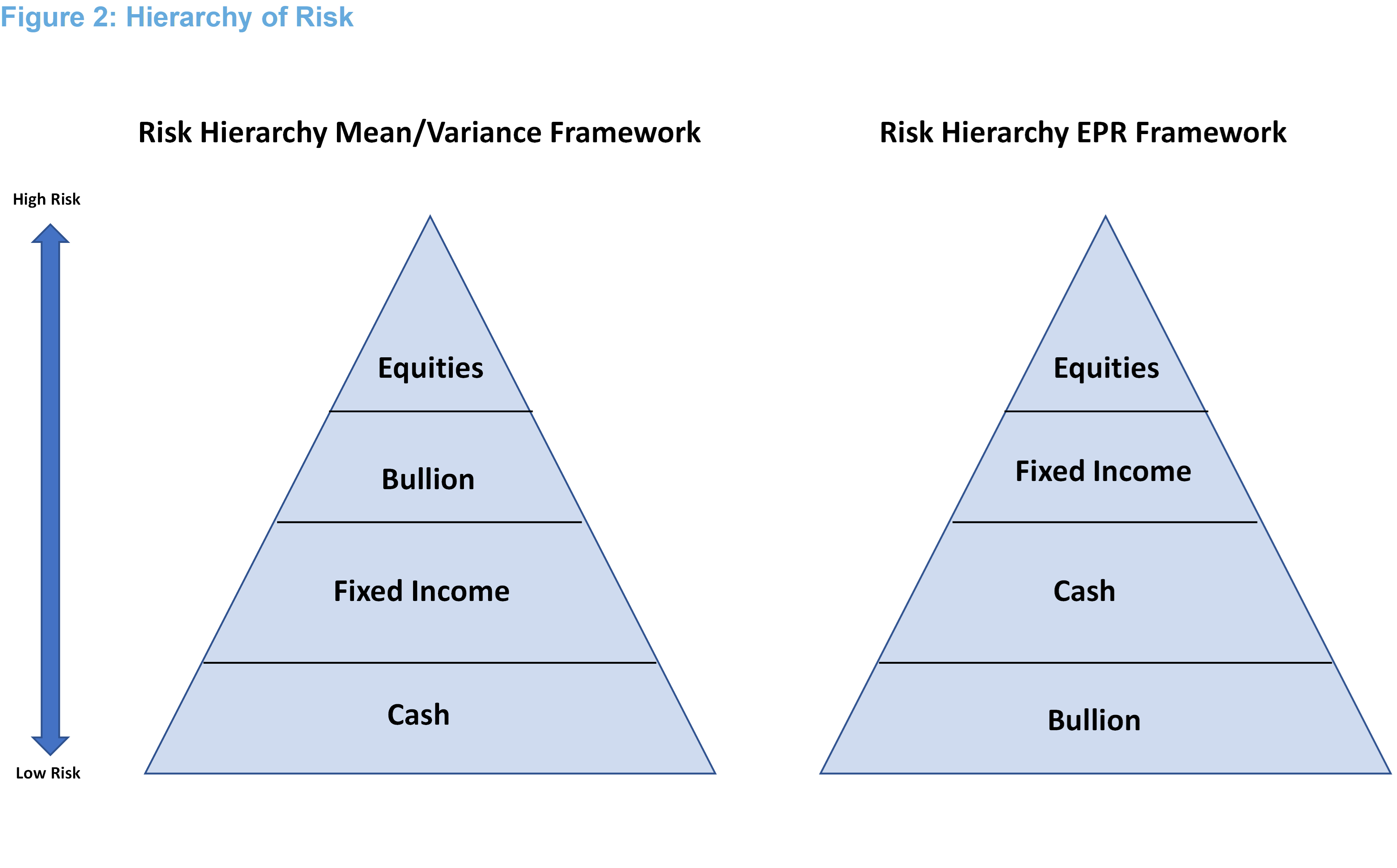

To add more colour to the concept of EPR in the context of investments, it is useful to consider the key asset classes set within a risk hierarchy pyramid. Within such a simplified framework the hierarchy of investments is established from lowest to highest risk with the allocation to each risk class, i.e. area within the pyramid, determined by the investors desired risk profile.

- Starting with equities, this is clearly the asset class that requires the greatest level of trust and hence incorporates the highest level of EPR. This can be seen by the fact shareholders entrust (a) managers to act on their behalf and in their best interest, (b) management to be capable of making the optimal entrepreneurial decisions and (c) associated stakeholders (suppliers, customers, employees, etc.) delivering on what is expected of them. But the trust goes beyond this to include external parties with no direct link to the company, such as governments and central banks etc, to provide an “environment” which is favourable to the ongoing viability/prosperity of the company. If this wasn’t enough legally the equity investor only has a residual claim on the company’s assets and profits. As a result, once equity is entrusted to a firm, the investor is exposed to a whole gamut of consequences due to misplaced trust including assumption of excessive debt, entrepreneurial error, excessive spending, poor budgeting, government policy changes etc. The ultimate ramification from misplaced trust is failure of the company.

- Bonds require a lower level of trust and hence exhibit lower EPR given that the cash flow profile is somewhat predetermined assuming no default and the keeping of bond covenants. Furthermore, a bondholder is less exposed to agency risk though to what extent depends on the borrower, loan covenants and collateral. An investor however still requires trust to assume the risk of potential default or other forms of credit risk. For example with government bonds, even though default risk is materially lower than corporate bonds, an issuing government may pursue financial repression which inflates away the real value of the bonds.

- Physical cash has an even lower level of EPR given that the principal is not at risk. However, holding physical cash still assumes some level of EPR as the holder of cash can still have their trust breached should the government pursue inflationary policies, normally via the oversupply of cash to deflate its real value.

- In this context, the only asset class which involves no, or little, assumption of EPR is the physical holding of hard assets; i.e. those assets which exhibit an intrinsic physical value and accordingly can be utilised as a means of exchange without the need for a third/external party guarantee. For an investor this includes the full suite of fungible commodities including real estate. However, given the impracticality involved in holding a physical basket of all commodities, such as wheat/cattle/oil etc, the physically held commodity universe is narrowed down to bullion; i.e. historically defined as predominantly gold and silver. In part this is a practical decision given the lower holding costs associated with bullion along with its associated characteristics of fungibility and portability. But it is also consistent with the historical role of bullion in many societies, including western, as the preferred commodity for utilisation as a means of physically storing portable wealth and a medium of exchange. It is worth noting that historically real estate has been, and still is, arguably more widely utilised as a source of wealth storage but it is unfortunately of little practical use as a medium of exchange outside of major transactions and, by definition, isn’t portable.

At this stage it may be tempting to assume that all that is happening is that risk, which was measured by return volatility, is simply being restated as EPR; i.e. the investments with the highest EPR also have the highest return volatility. That is correct to a point but there is one material difference which is worth emphasising. In a world where risk is measured by return volatility then physical cash, and even cash at the bank, becomes the risk free asset; i.e. it possesses the lowest return volatility of all the asset classes. By comparison bullion which exhibits higher return volatility will sit above cash and may even sit above fixed income. However, where EPR is the measure of risk, cash whether held physically or within a financial institution, is no longer the risk-free asset. The reason for this is that cash in a modern society depends upon guarantees from external parties to give it the requisite value/properties to serve as a store of value and a medium of exchange. On the other hand, physically held bullion becomes the risk-free asset as it does not exhibit EPR even though it may exhibit volatility in returns; i.e. its intrinsic value facilitates utilisation as a store of value and a medium of exchange rather than some third party guarantee.

There are two logical extensions to the EPR framework which are interesting to consider.

Firstly, between types of physical bullion there may also be differential levels of EPR. For example, historically in times of crisis, where governments have aimed to utilise bullion to back their currencies, gold has normally been the preferred medium over silver. There are several reasons for a bias towards gold over silver when backing a currency including gold being largely non-reactive, easier storage given its higher value/weight ratio, relatively limited commercial uses etc. The result is that apart from the physical mintage of coins the use of gold has historically been the preferred means of backing currencies. This has implications for investors in gold as during such periods there has been an associated bias towards limiting the ability of private citizens to hold bullion. More recent examples of this bias are United States Gold Confiscation 1933 (in force until 1975), Australian Gold Confiscation 1959 (in force until 1976) and Great Britain’s Gold ban 1966 (in force until 1979). Given the historical experience associated with gold confiscation by governments during periods of crisis it could be viewed that the EPR for gold is higher than that for silver.

Secondly, it is interesting within an EPR framework to consider where crypto currencies may fit within the hierarchy of risk. This is particularly relevant as many investors view crypto currencies as a 21st century alternative to physical bullion. The argument follows that, as crypto currencies are completely separated from the traditional financial system, they do not exhibit external party risk. A potential limitation with this argument is that it ignores the EPR associated with the maintenance of the entire technological architecture/infrastructure that facilitates the operation and trading of cryptocurrencies. Put another way “What use is a crypto currency without access to a computer/internet or even electricity?” When considered in this context crypto currencies may be viewed as entailing material EPR with a level of trust akin to or even above equities. Accordingly, the idea of cryptocurrencies as the modern day equivalent to physical bullion is somewhat tenuous when considered from an EPR perspective.

Considering risk from a different perspective can alter how investors view the characteristics of various asset classes. Most importantly the determination of what comprises a “risk free” asset can change. Within, and even outside of a formal mean variance framework, most investors would consider cash as the risk-free asset and typically comprise a material proportion of a portfolio. Within such portfolios bullion will typically comprise relatively small proportions being mainly viewed as a source of return diversification. Indeed, bullion is often viewed by many investors as an anachronism harking back to times long gone. Yet considering risk according to the EPR framework shifts the focus of portfolio construction and results in bullion becoming the risk-free asset. The difference in what is viewed as the risk free asset can have material implications for investors as, if bullion is the risk free asset, they risk being systematically underexposed to the lowest risk asset class over the longer term. If this is the case then the change in perspective will inevitably move investors away from traditional types of diversified portfolios and more towards the types of diversified portfolios referred to by such terms as Fail Safe Investing and Permanent Portfolios. Such portfolios have materially higher exposures to bullion as they are often equally weighted between equities, fixed income, cash and bullion. Accordingly, how an investor views risk can have a material impact upon the preferred long-term composition of a diversified portfolio.

4 topics

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...

Expertise

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...