Aussie bank bond supply shock finally arrives

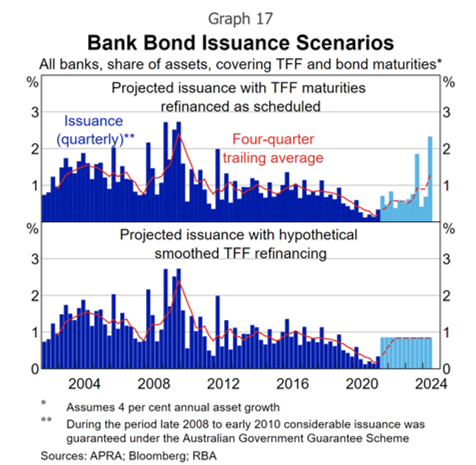

In the first half of 2021 we forecast an Aussie bank bond supply shock in the second half of that year and through 2022/2023 as banks started preparing to repay the $188 billion they borrowed from the RBA under the so-called Term Funding Facility (TFF). As the RBA itself has forecast in this Bulletin paper, banks are not simply going to repay the $188 billion when it falls due in 2023 and 2024. More precisely, the RBA comments:

Banks are unlikely to refinance their TFF drawdowns right at the time they are scheduled to mature. In liaison, banks have flagged plans to issue bonds earlier than scheduled TFF maturities (‘pre-funding’)

The RBA helpfully presented a hypothetical "smoothed issuance" scenario, which is the second chart in the image below. Based on the run rate this financial year, banks are certainly following this stabilised issuance profile, which is what you would expect from conservative bank treasurers.

How much debt do banks need to issue?

Our credit research team has carefully modelled precisely how much money the banks need to raise to (1) repay the TFF, (2) replace the $140 billion Committed Liquidity Facility (accounting for the composition of their CLF portfolios), and (3) fund their overall balance-sheet growth, which is currently very strong. You can read about this modelling here. Our best current estimate is about $133 billion per annum of debt issuance from the four majors over the next 3 years, which is slightly less than the $147 billion average issuance from these banks in the 10 years preceding the pandemic. So it is not such a big deal.

Since early 2021, we have projected that the credit spreads on 5-year major bank senior bonds would need to push wider from the post-COVID tights of just 28 basis points (bps) over the quarterly bank bill swap rate (BBSW) back to between circa 70bps to 120bps, which is in line with their historic trading range in the post-GFC and pre-COVID periods. At the time, this was a highly contrarian view.

In Aussie dollars, the initial 5-year senior bond issues did indeed start emerging in the first half of 2021 and then accelerated in the second half with issues from both a range of regional banks and NAB. The majors concentrated most of their 2021 issuance offshore, which was smart, locking in a lot of cheap funding.

Bond tsunami and the rise of the fixed-rate format

In January 2022 the Aussie dollar bond tsunami has really revved up. We had a record $4 billion 5-year issue from CBA, pushing spreads up to 70bps (into our target range). This has been accompanied by 5-year issues from the likes of Suncorp, Bank of Nova Scotia, Sumitomo, Rabo and, yesterday, Westpac. (We participated in CBA, Suncorp, BNS and Westpac.)

Westpac's $2.75 billion, five-year deal was another well-executed trade, printing at 70bps over BBSW, or exactly in line with the CBA level. The Queen of Credit (aka Westpac's Treasurer Jo Dawson) was hardly going to pay more to raise money than the King of Credit (aka CBA's Terry Winder).

Another forecast we've been ventilating of late has been the rise in the popularity of fixed-rate, as opposed to floating-rate, tranches in these Aussie bond issues. This is a function of two things. First, as the $140 billion CLF is closed, banks are going to find it very difficult to bid in large size for one another's bond issues (tellingly only around 18% of the Suncorp 5-year deal was bought by banks).

Prior to the GFC, most bond issues in Australia were fixed-rate, not floating. It was really the advent of the CLF, and the desire of the banks themselves to buy floating-rate bonds, which pushed this class of product.

The second driver is APRA moving to assess super fund performance using the Composite Bond Index, which is a long-duration, fixed-rate benchmark. To minimise tracking error to this index, super funds will shift from floating-rate credit to more fixed-rate exposures.

In CBA's monster $4 billion trade, they printed a huge $900 million fixed-rate tranche, which materially outperformed the floating-rate counterpart in subsequent secondary trading. In Westpac's $2.75 billion deal, the fixed-rate skew was 31%, notably much higher than CBA's 23% (ie, Westpac also printed a very large $850 million fixed-rate tranche, which was even greater on a relative basis).

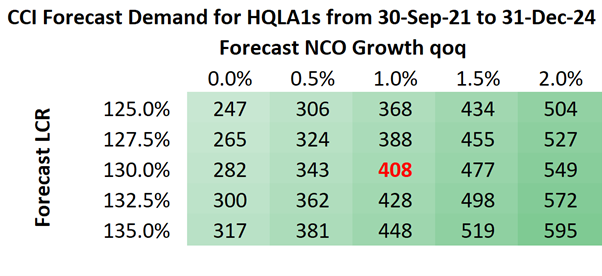

$282 billion to $487 billion of government bond-buying

One question is what the banks are going to do with all this money. They obviously need to repay existing bonds as they mature and fund their robust balance-sheet growth. My colleague Dr Stephen Parker recently shared our analysis that shows they need to buy between $282 billion and $487 billion of government bonds to (1) replace the $140 billion CLF that counted as a liquid asset for their Liquidity Coverage Ratios (LCRs) and (2) replace the excess cash that they currently hold at the RBA, which will disappear over time.

You can see the number of bonds the banks have to buy in the table below as a function of their LCRs and their Net Cash Outflows (NCOs generally track deposit growth, which in turn normally follows balance-sheet growth given new loans automatically create new deposits). LCRs are enormously volatile (moving as much as 20-30 percentage points on a single day for banks), which is why banks hold a minimum 25-35% buffer over APRA's 100% floor LCR.

.png)

Bank treasurers are now happy to acknowledge that there's a massive bond-buying task ahead of them (they have only very recently got their heads around the volume required, in our view). Even if we slash our central case of $408 billion of bond-buying back to, say, $300 billion, it represents $100 billion a year. Based on the banks' government bond portfolio splits, that would be allocated about $70 billion to State bonds and $30 billion to Commonwealth bonds. In our central case, the actual numbers are $136 billion a year, which is split $95 billion a year to the States and $41 billion to the Commonwealth.

To put that in perspective, $95 billion a year of bond-buying each year is the equivalent of 4.75 standard RBA QE programs for the States. As treasurers concede, the volume task is so large banks do not have the luxury of deferring this buying into 2023 and 2024: they need to be continuously buying all new issues and averaging-in through time, exactly as they did in the bank bond market when they could buy those bonds for their CLF portfolios (ie, banks would buy every new major bank issue of senior debt for their CLF books).

Why does $244 billion of excess cash banks hold at the RBA disappear over the next 3yrs?

By way of further explanation, when the RBA lent the banks $188 billion via the TFF, it created $188 billion of digital cash that was deposited in the banks' Exchange Settlement Accounts (ESAs) that they hold with the RBA.

As the TFF is repaid this year and in future years, this $188 billion automatically disappears (ie, the digital cash the RBA created is destroyed). The problem is that this $188 billion is currently counted in the banks' LCRs. So it needs to be replaced with new high-quality liquid assets (HQLA1): and the only assets that count as HQLA1 are government bonds (and ESA cash).

This problem will be exacerbated by a few things. As I mentioned above, the faster a bank's balance-sheet growth, the greater their demand for HQLA1 because as they write new loans, they create deposits, and they have to hold liquid assets (government bonds) as security against these deposits. Another important factor here is the RBA ending its bond-buying program in mid-February.

The banks had assumed that the RBA's third QE program would generate between $100 billion and $150 billion of digital cash via money printing, which would be included in their LCRs. This was meant to assist in the transition to closing the $140 billion CLF in 2022, which is also included in their LCRs.

Instead, the RBA will have only generated about $76 billion of digital cash from its third round of QE. Put differently, there will be about $25 billion to $75 billion less digital cash created in 2022 than the banks had previously assumed.

That will mean they will have to buy more government bonds (HQLA1) than they had previously planned to replace the $140 billion CLF in 2022 (and in contrast to the RBA, which buys Commonwealth/State bonds in an 80/20 split, the banks typically buy according to a 30/70 split). Then you have the partial repayments of the TFF in 2022.

A final variable is bonds maturing off the RBA's own balance sheet. As the money the RBA invested in these bonds is repaid, the digital cash it created is destroyed. This cash was also included in the banks' LCRs and will have to be replaced with HQLA1.

Right now there is $420 billion of excess cash held by banks on deposit at the RBA. If you take $56 billion of bonds maturing off the RBA's balance sheet in the next 3 years plus the $188 billion of TFF repayments, banks will lose $244 billion of ESA cash that will have to be replaced by HQLA1 over the same period. And they will have no choice but to smoothly average in over time. You then need to add in the additional liquids they will have to hold as the dollar value of their deposit base climbs over time.

No matter which way you slice and dice it, this new form of QE via banks buying government bonds will likely be even larger than the RBA's efforts and allocated very differently between securities issued by the States and those issued by the Commonwealth.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

2 topics