Australia is heading for a housing-driven economic slowdown

Conrad Capital Group

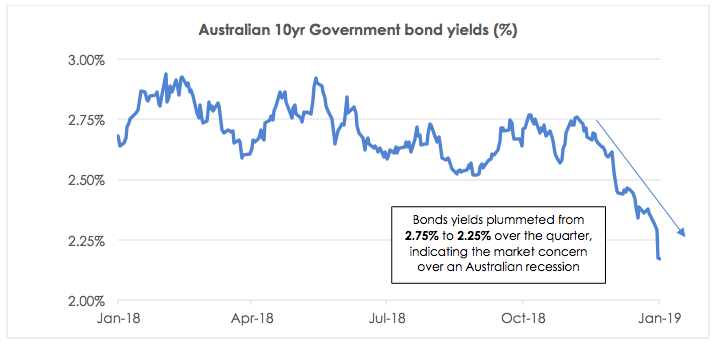

Australian bond yields declined rapidly over the December quarter, anticipating a major slowdown in the Australian and global economy. Real estate has a correlation to bonds, a function of the leases it has in place with its tenants and generally performs well in weak equity markets.

In this excerpt from the Newgate Real Estate and Infrastructure Fund newsletter, we make the point that while the real estate sector does have a correlation to the economy, it is not a homogenous sector.

Real estate can differ significantly in its risk attributes. For example, a distribution centre leased to Woolworths for 20 years is a highly defensive investment, essentially a Woolworths bond. In contrast, a real estate company involved in the development of real estate is highly risky in a weakening economic environment.

We first make the case of a significant slowdown, if not contraction, in the Australian economy. We then describe the rationale for our short position in the retail and residential real estate sectors. We describe why we think that a slowing economy will eventually impact sales and rental rates for these sectors.

An Australian recession?

We believe that Australia is heading for a housing-driven economic slowdown. we explain our view here, examine the bank's exposure to the residential market, and discuss what happens when house prices fall, including Australia's experience in the early 1990s.

By way of background, Australia has not had a recession for 27 years, a global record. The premise for our view on the Australian economy is driven by our negative view on the Australian housing cycle.

“Real estate constitutes a large fraction of the total wealth in any economy, and in turn generates a large component of banking debt. Consequently, real estate booms are often accompanied by periods of intense speculation involving expansion of credit and banking activity, stimulating the economy. When the bubble bursts, the resulting bad loans, defaults and unemployment can throw an entire economy into recession.” - John Sterman

We have written previously that Australia has all the ingredients of a major housing market correction – except contracting credit growth. We think this ingredient has now been added because of the revelations from the Royal Commission into the banking sector.

The Commission highlighted the lax lending practices of the Australian banking system and has seen them become a lot more selective about who they lend to. Willingness to lend has declined.

On the other hand, we also have falling willingness to borrow. The evidence points towards borrowers becoming more cautious about using high levels of debt to buy an asset that appears to be declining in value. We think the widespread commentary about forecast house price declines of 15-20% are scaring potential buyers and reducing their willingness to borrow:

“Australian house prices falling at fastest rate in a decade”

“Sydney and Melbourne properties have now dropped 11% and 7.2% respectively compared with 2017 peak”

The Guardian, January 2019

We will not argue the case for the overvaluation of the Australian housing sector. There is ample evidence to support it. For example, net rental yields on property in Melbourne and Sydney is 2.5%, the lowest since 1950.

Bank exposure to the residential market

The Australian banking system relies on housing like no other banking system globally. Residential loans represent 62% of all Australian bank loans.

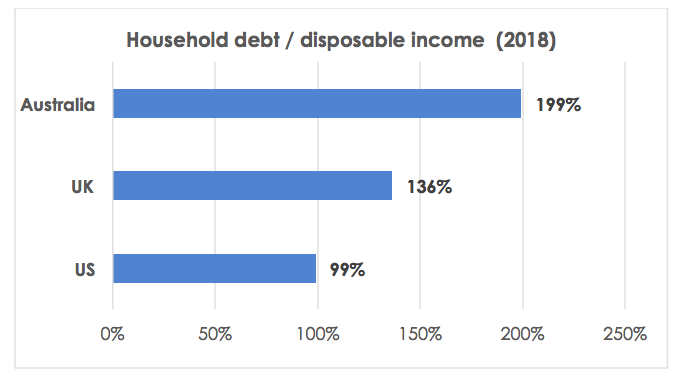

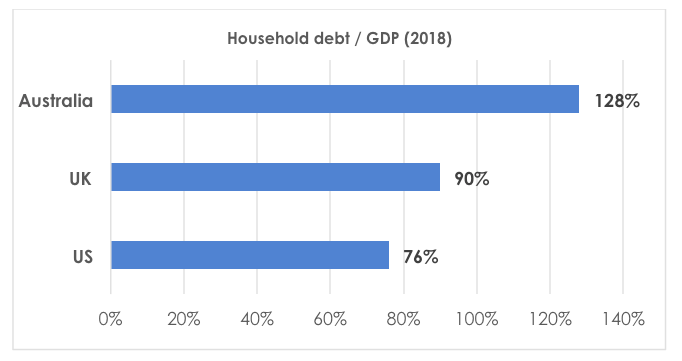

It is no surprise that we are here. Since 1977, Australian banks have grown their residential lending books by 13% per annum. GDP growth has only averaged 6% over this time. This has caused household debt compared to disposable income to move from 40% to 200% - the highest in the world.

On the back of this growth, Australian banks have been an excellent investment, increasing in relative terms by seven times compared to your average world bank. The banking sector now represents 30% of the S&PAS200.

Source: Citigroup

Source: Citigroup

What happens when house prices fall?

As house prices fall, there is an impact on the economy as the population feels less wealthy – the well-known ‘wealth effect’, which psychologically crimps consumption. But one of the less known issues with falling house price is ‘reduced mobility’.

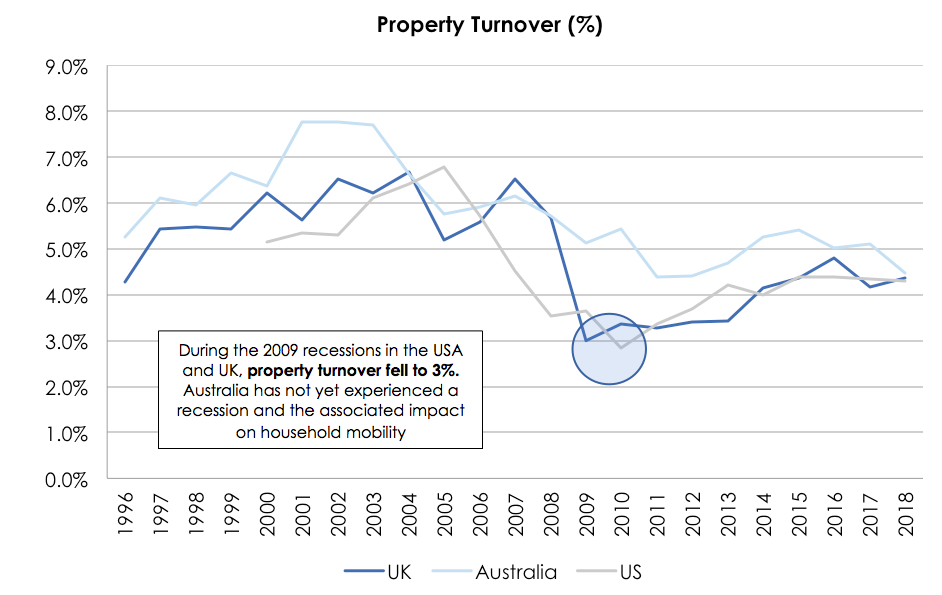

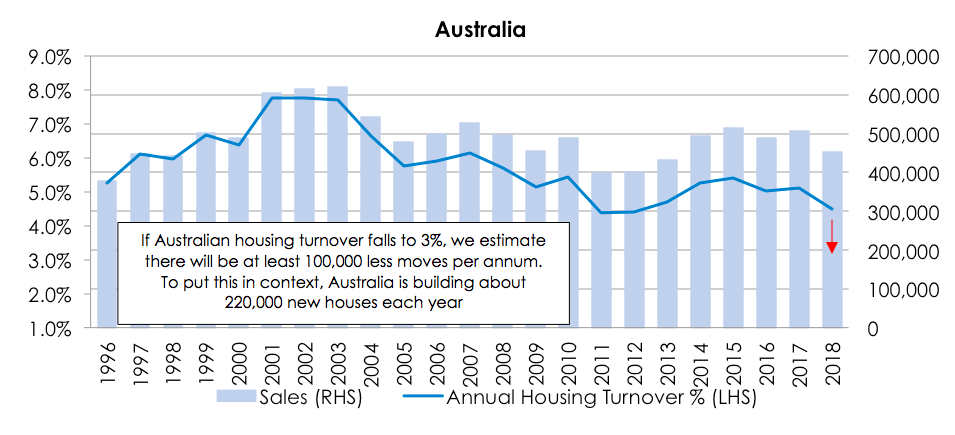

When house prices fall, people move less. We saw this during the US and UK housing market correction during the global financial crisis. Housing turnover dropped from 6% to 3%. This study describes the phenomenon:

“The new study’s findings corroborate the 2010 results: Negative home equity reduces household mobility by 30 percent”

Sources: US: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, National Association of Realtors; UK: Office for National Statistics, Ministry of Housing; Australia: ABS

Mobility matters, because when people move, they spend on appliances, furniture and other consumer durables. Lower mobility negatively impacts the retail industry, one of the major sectors of the economy.

Housing construction

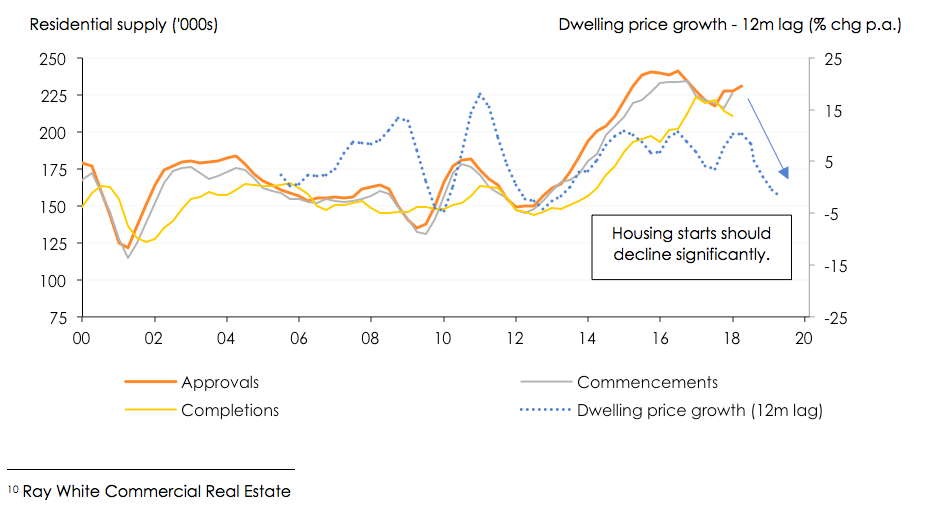

The other major impact of falling house prices is housing construction. House prices and housing construction are highly correlated. Price is a signal, and it is communicating lower housing construction ahead. This is an additional issue for the Australian economy. Construction is the third largest industry in Australia, producing over 8 per cent of our GDP and employing roughly 10% of the workforce. The construction industry is also a major consumer of steel, concrete, and other building materials.

To exploit this scenario unfolding the Newgate Real Estate and Infrastructure Fund is short securities exposed to the Australian residential market. This strategy did not deliver the results we expected over the past six months, but we have high conviction it will deliver over 2019.

Retail Real Estate during the last recession

The other major real estate sector we are concerned with is retail real estate.

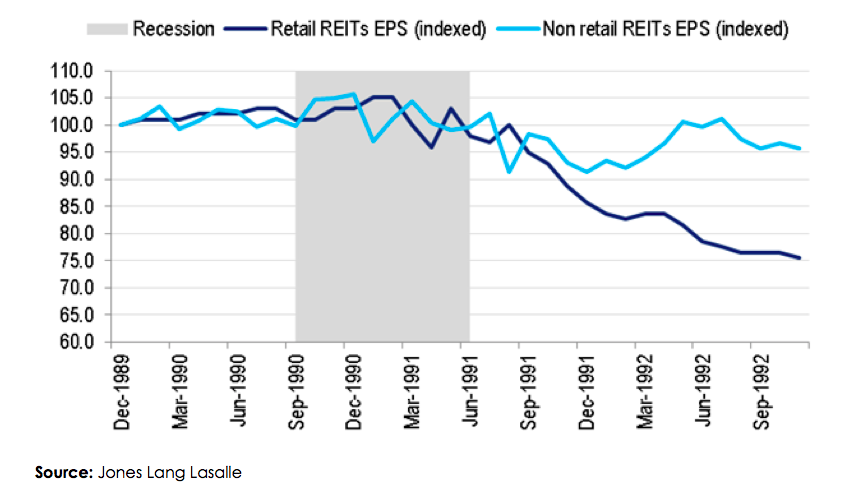

With assistance from Adrian Dark, Head of Real Estate at Citigroup we reviewed how earnings changed during the last recession in the early 1990s.

As the chart below clearly illustrates, retail rents fell, but it took six to twelve months after the recession for it to occur. This is as expected because leases protect earnings in the short to medium term.

We should expect retail rents to contract during a recession in the Australian economy. Retail rents are cyclical, it is just that we have not observed this cyclicality over the past two decades because of Australia’s unprecedented economic expansion.

Online retailing

Retail real estate is not just contending with a slowing economic cycle. Online retailing is growing exponentially, as we culturally become used to it as a method of purchasing goods and services.

It has taken almost two decades for online retailing in Australia to reach 6.6% of total retail sales. We think we are moving to the point where it begins to grow in a more exponential fashion. We expect online retailing to follow the typical technology “S-Curve”. The diagram below illustrates:

The need for” social interaction” is not an acceptable counterargument

One of the major arguments against the threat of online retailing is the human need for social interaction. We are not denying this. We are not calling the end of shopping centres, just a contraction in space requirements and a recalibration of rents.

Retailers have been slow to respond

Retail landlords have had nearly two decades to adapt to online retailing, and we are only now starting to see any strategic responses to the threat. This obvious observation from the Boston Consulting Group from 2006, 12 years ago:

“Ecommerce presents incumbent bricks and mortar retailers with a serious dilemma."

We think one of the industry’s watershed moments was when the Lowy family orchestrated the sale of the shopping centre giant Westfield Holdings in December 2017.

After many years of research and study the Lowy family took the view that combating online retailing was going to be extremely difficult. Frank Lowy after 58 years of growth sold his shopping centre portfolio to European shopping centre company, Unibail-Rodamco. Unibail’s share price has fallen 30% since this transaction.

Australia has low penetration relative to other developed markets

Macquarie Bank’s research highlights that Australia is ‘under-penetrated’ across a range of retail categories. For example, Australia has just a 2% online penetration in grocery retailing, this compares to China and the UK at 5%. But the research also shows online grocery retailing in Australia is growing rapidly, at 25% per annum.

Other major categories with low penetration rates include home, garden and auto, where Australia has just a 5% penetration rate, compared to a 20% rate in the UK. In electrical and office, Australia has a 6% penetration rate, versus the US at 26%, and the UK at 19%.

While just one point of view, the Merrill Lynch global technology team had this to say about online retailing:

“We think global penetration can increase from 11% currently to in excess of 25% over time, significant runway for continued solid industry growth.”

Density is not a problem

Another of the major counterarguments from retailer and retail landlords against the online threat is that Australia is too geographically dispersed, and therefore logistically, online retailing cannot work.

This argument is insufficient because it does not consider that an online retailer can choose to only serve the high density areas of the Australia. You could argue Australia’s density is perfect for online retailing penetration:

“Over 85% of Australians lived in urban areas and nearly 70% lived in our capital cities, making Australia one of the world’s most urbanised countries”

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

What will happen to retail landlords? The UK analogue

To gain a glimpse of what may happen to Australian retail landlords we look to the United Kingdom.

In the UK, we have seen retailer’s top line revenue growth hampered by just over two years of negative consumer confidence, rising consumer credit and rising indebtedness. A poor economic backdrop.

These factors are conspiring with rapid online growth to cause foot traffic at shopping centres to gradually decline over the past three years, with an acceleration over the past 12 months.

To highlight the impact on the capital value of shopping centres we have highlighted UK shopping centre company Hammerson (HMSO). Hammerson trades at a 40% discount to book value. The stock price has fallen 40% over the past six months.

In response to market pressures, Hammerson had management consultants McKinsey undertake a review that made two obvious recommendations:

- Hammerson should increase exposure to high growth retail categories and reduce weighting to outdated and disrupted concepts such as department stores (!)

- Hammerson should steer the tenant base towards formats such as healthcare, co-working, and logistics

McKinsey’s suggested strategy for Hammerson is obvious and appealing but unlikely to be effective. Our analysis suggests there are not enough new “Amazon proof” tenants to offset the vacancy created by outgoing or contracting tenants.

Our assessment is that 50-60% of current shopping centre space is threatened by online commerce. A major component of this space is apparel, the highest rent paying category and representing about 30% of total shopping centre space.

As evidence, a very recent Macquarie report illustrated the results of a major survey of retailers. They took 30 detailed responses which in aggregate represents at least ~2,300 stores:

“Store network rationalisation is set to continue, with 24% indicating an intention to decrease space over the next 12 months , with 21% indicating more than 10% of network space”

We were surprised at the results of this survey. A space contraction of this magnitude will have to have a material negative impact on rents. The other way landlords will try to stem this exodus is by paying ‘incentives’ – basically paying tenants to stay vacated. Either way this will likely reduce the value of retail real estate assets.

Rent reduction is only a short-term solution for the retail shopping centre industry as online retailing continues to evolve and improve, particularly on the logistics front.

At an extremely simplified level, we see the industry playing out over time like this:

- Retail rents will fall, and shopping centre values will fall with them

- Shopping centre owners will find themselves undercapitalised, debt providers will want debt levels reduced. Not all will be able to deal with this and will exit the industry

- Many operators will not have the skills and capabilities, nor the capital to remix and reinvent their shopping centre, and will exit the industry

- The new owners of shopping centres will be operating a markedly different asset. Shopping centres will comprise much greater entertainment and experiential areas. There will also be much greater mixed-use activities, such as hotels, residential and office

Our positioning

We are short retail shopping centres in the Fund. We expect the next 12 months will see rents fall on the back of a slowing economic cycle as well as increasing competition from online retailers. This will reduce the value of shopping centres materially. The process to reengineer shopping centres will be painful and expensive.

5 topics

Tim has 25 years’ experience in the investment and securities markets. Tim was a partner of Goldman Sachs and during his 16-year tenure at the firm had senior experience across all areas of equities investing.

Expertise

Tim has 25 years’ experience in the investment and securities markets. Tim was a partner of Goldman Sachs and during his 16-year tenure at the firm had senior experience across all areas of equities investing.