Australia’s next mining boom? The role of critical minerals in renewable energy

Australia’s resources sector is already one of the largest and most advanced in the world. Our well-established mining industry and world-leading mining equipment and technology make Australia an exceptional destination for critical mineral investment. In this month’s Core Offerings, we take a look at what defines a critical mineral, their key role in the energy transition, the likely insatiable demand for them in the future, and opportunities for Australia to be a key player in the critical minerals space.

The global energy system is in the midst of a major transition

There’s no doubt that 2022 will be remembered as one that brought about severe disruptions to energy markets. Still recovering from the supply shocks of the COVID-19 global lockdown, energy markets faced another supply crisis when one of the world’s largest suppliers of oil and gas, Russia, invaded Ukraine. The price of oil and gas surged, fuelling inflationary pressures, and making many countries question the security of their existing energy supplies. And this conflict appears likely to extend into 2023.

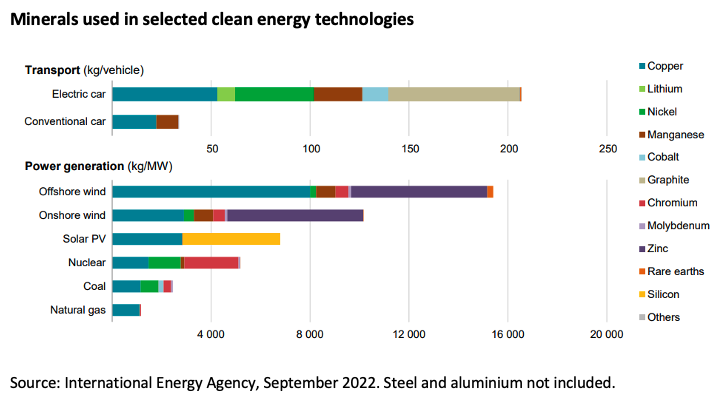

Adding to all this uncertainty, the global energy system is in the midst of a major transition to renewable energy. The efforts of companies and countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) globally will likely lead to the massive deployment of a wide range of clean energy technologies, many of which rely on critical minerals, like copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth minerals.

Renewable energy, like wind turbines and solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles (EVs), provide the ability for countries once reliant on fossil fuels to generate their own electricity domestically. This helps to reduce geo-political risk while simultaneously meeting their decarbonisation objectives. As the energy system calls for an evolving approach to both energy security and decarbonisation, there is no doubt the world will need unprecedented volumes of critical minerals to fuel the transition.

Australia has many of the elements the world needs to make renewable energy infrastructure. It is also already a world-leading critical mineral exporter, currently supplying many countries with high-quality, ethically-sourced minerals using environmentally sustainable practices:

- It ranks in the top five globally for resources of critical minerals like antimony, cobalt, lithium, manganese ore, niobium, tungsten, and vanadium.

- It is one of the world’s top producers of lithium, rutile zircon, and rare earth elements.

- It has the potential for more undiscovered minerals.

Currently, many critical minerals come from a small number of countries, with the world’s top three global producers of critical minerals controlling well over 75% of global output. This high geographical concentration, the instability of markets, and various environmental and social impacts from increasing mining in some areas all suggest that critical mineral markets will be subject to price volatility, geo-political influence, and possible disruptions to supply in the coming years. This will have a significant impact on mineral-rich countries, including Australia.

According to the International Monetary Fund Australia is in pole position to benefit from a six-fold increase in demand for critical minerals worth USD 12.9 trillion over the next two decades. Consequently, we believe Australia is in the driver’s seat to compete successfully with China and other global players in the critical mineral space.

What are critical minerals?

According to Geoscience Australia, a critical mineral is a metallic or non-metallic element that has two key characteristics. Firstly, it is deemed essential for the functioning of modern technologies, economies, or national security. Secondly, there is a risk that its supply chain can be disrupted.

Many critical minerals are used in renewable energy infrastructure, such as EVs, wind turbines, solar panels, and rechargeable batteries, with the types of mineral resources used varying by technology. Lithium, cobalt, and nickel play a central role in enhancing battery performance and longevity and providing higher energy density. Lithium is also a core metal for EV batteries.

Rare earth minerals make up a specific, highly useful category of their own within the critical mineral family. Including elements such as lanthanum, cerium, and neodymium, rare earth minerals are used to make powerful magnets that are vital for wind turbines and EVs. Electricity networks also need large amounts of copper and aluminium. Hydrogen electrolysers and fuel cells require nickel and platinum group metals depending on technology type, and copper is an essential element for almost all electricity-related technologies. There is no doubt that to achieve the ambitious global net-zero goals, there will be accelerating demand for most, if not all, critical minerals.

Insatiable demand expected

The rapid acceleration of renewable energies globally suggests there will be significant demand for critical minerals in the coming decades. The World Bank suggests that the production of critical minerals will increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet the growing demand for clean energy technologies. Primary drivers of demand will be:

- Rate and sales of EVs—A steep EV penetration curve is expected.

- Renewable energy infrastructure demand—This includes solar, and wind turbines.

- Battery storage—This is still the main driver of cost reductions. It is likely to be a short-term focus and costs will need to fall further for penetration rates to increase. Supply of inputs, many of which are critical minerals, will be tight.

- Electrification of everything

Demand is subject to large variations, leading to a possible range of future outcomes that impact companies’ investment decisions. This could, in turn, cause supply and demand imbalances in the years ahead. Each mineral carries different demand risk depending on whether it is cross-cutting (needed across a range of low-carbon technologies) or concentrated (needed in one specific technology). Copper, chromium, and molybdenum are examples of cross-cutting minerals where demand conditions are likely to be more stable.

Concentrated minerals, such as graphite and cobalt, are needed for only one or two technologies and, therefore, possess higher demand uncertainty, as technological disruption could impact demand conditions.

A rapid rise in demand is expected to drive deficits ahead

The prospect of a rapid increase in demand for critical minerals raises questions about the availability and reliability of supply. COVID-19 and the Ukraine war have had a significant impact on global supply chains, and it is reasonable to factor in ongoing supply disruptions for critical minerals going forward (noting that supply outages as a percentage of the global production are commonplace in forecasting supply/demand balances for commodities such as oil and copper).

Currently, global supply chains for critical minerals are opaque, mostly due to the fact that the world’s richest critical mineral resources are in countries that are typically less developed or pose geo-political and trade risks. In addition, the critical mineral supply is more geographically concentrated than that of oil or natural gas.

For lithium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals the top three producing nations control over three-quarters of global output. Democratic Republic of Congo and China are responsible for some 70% and 60% of the global product of cobalt and rare earth respectively.

The concentration is even higher for processing operations. One of the biggest challenges in the critical minerals sector is the current concentration of critical mineral supply chains in China. Diversifying global supply chains has become a key political focus for various governments around the world as they attempt to shore up their access to critical minerals.

Australia is in the driver’s seat

Large and vast critical mineral reserves put Australia in a unique position to diversify the global supply of critical minerals. Global businesses in the US and elsewhere are looking to de-risk their supply chains and secure stable sources of critical minerals. Australia’s government has also indicated a desire to attract more investment across the supply chain, from exploration and extraction to production and processing.

In addition, Australia’s rule of law creates an investment environment of lower political and sovereign risk. Investors can have greater confidence in consistent and transparent management of economic settings and environmental protection as they operate in a strong and well-established resources industry.

The US is already looking to diversify its critical mineral supply chains and is heavily focused on Australia playing a key role. Under the recently approved Biden Administration Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), USD 369 billion has been committed to battle climate change in one of the largest climate spending plans ever passed in the US. Tax credits will make EVs cheaper, there will be hefty fines for high-polluting oil and gas companies, and funding available to expedite the production of solar panels and wind turbines.

Among the commitments, several grants have been provided to Australian companies to assist the US in reducing its reliance on China for the majority of its critical mineral needs. The IRA also makes new and used EVs more affordable for consumers via tax credits, which further support minerals for batteries, required from US allies, such as Australia.

Environmental and social issues of more mining

The sheer scale and role of critical minerals to meet the world’s ambitious net-zero goals mean that the environmental and social footprint of mining these minerals needs to be understood. Extraction and production processes can be mining and carbon-intensive, creating disruption to local communities.

If managed and mined responsibly, critical mineral development can contribute positively to decarbonisation, but if not managed properly, there can be a myriad of negative consequences including:

- A significant increase in carbon emissions from energy-intensive mining and processing activities.

- Environmental impacts, including biodiversity loss and social disruption due to land use change, water depletion and pollution, waste-related contamination, and air pollution.

- Social impacts stemming from corruption and misuse of government resources, fatalities and injuries to workers and members of the public, as well as human rights abuses, including child labour.

Despite the higher mineral intensity of renewable energy technologies, the scale of associated GHGs is a fraction of that of fossil fuel technologies. That being said, the carbon footprint of mining critical minerals must not be overlooked when considering making an investment in this area.

Where are the investment opportunities?

Some of the structural thematics at play include:

Decarbonisation—An ongoing push towards sustainability means decarbonisation will continue to be a focus for corporations, governments, and investors, and a key opportunity (and risk) for markets.

EV penetration—For EV penetration to increase, battery cell supply will also need to rise.

Energy alternatives—Renewable energy plays a key role in the transition. Long-term climate change targets and the rising share of electricity consumption provide a strong tailwind for the use of renewable energy to meet these challenges.

Learn what LGT Crestone can do for your portfolio

With access to an unrivalled network of strategic partners and specialist investment managers, LGT Crestone offers one of the most comprehensive and global product and service offerings in Australian wealth management.

Click 'CONTACT' to find out more.

3 topics