Australian home ownership peaked in 1966. How do we make property more affordable?

“City land booms have always been a snare of the people of the Australian colonies” and “despite various efforts of governments, the [Sydney real estate]system seems to have run out of control and the inflated values have become institutionalised”.

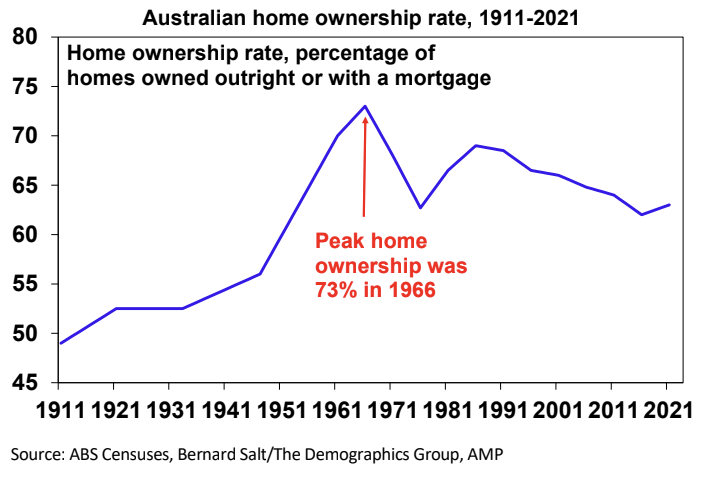

Since the mid-1960s, though, the home ownership rate has declined as documented in a fascinating report by the well-known demographer Bernard Salt together with AMP entitled ‘What wealthy means to Australians in 2023’.

Peak home ownership

As the report notes, at the time it was all about “getting married, having kids, buying a house and holding a steady job”.

The question is whether this decline reflects deteriorating housing affordability flowing from years of property booms, leading to a fading in the “Aussie dream” which is centred on home ownership or whether it’s something deeper.

A lot has happened since 1966

- More years spent in education, people starting work further into their twenties, the increasing importance of career, rising female participation in the workforce, and a desire for more experiences and travel have all seen family formation pushed into the late twenties.

- Starting with the baby boomers, subsequent generations have not felt the same need for the security offered by home ownership that their forebears felt in the mid-1960s. This partly flowed from dimming memories of the travails of the Great Depression and World War Two, rising levels of economic prosperity, greater choices for spending with the growth of travel and the café culture (Bernard Salt’s “smashed avocado on five grain toast”) and a perception, based on seeing their parents experience, that owning a home is not necessarily the way to happiness.

- Related to this, there is an element of Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” at work here. In Maslow’s hierarchy the first set of needs is physiological (eg, food and shelter), then safety and security (eg, health, employment and property), followed by love and belonging (eg, friendship and family), self-esteem (eg, confidence and achievement) and finally self-actualisation (eg, morality, meaning and inner potential).

In the post war years, the focus for many Australians was on physical needs including shelter and a perception that this will provide safety and security. Today, many still struggle with this but arguably the prosperity seen over the last 50 years has seen many more move on to focussing on self-actualisation.

Witness the growth of books and material directed to this in book shops and online. In 1966 it was only just starting to become a thing with hippies trying to seek enlightenment. For some, individual freedom may not be seen as consistent with the financial commitment required by a mortgage.

- Increased life expectancy – such that a retiree today may spend 25 years in retirement but maybe only 5 in the 1950s – and the growth of Superannuation from the early 1990s meant increased focus on retirement and wealth beyond the home.

- Increased diversity in terms of cultures & sexual orientations may have reduced the perceived importance of home ownership for some.

But what about housing affordability?

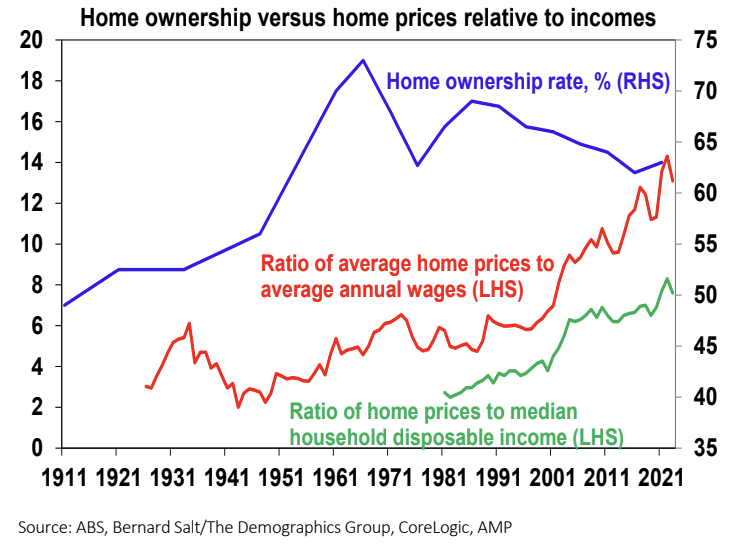

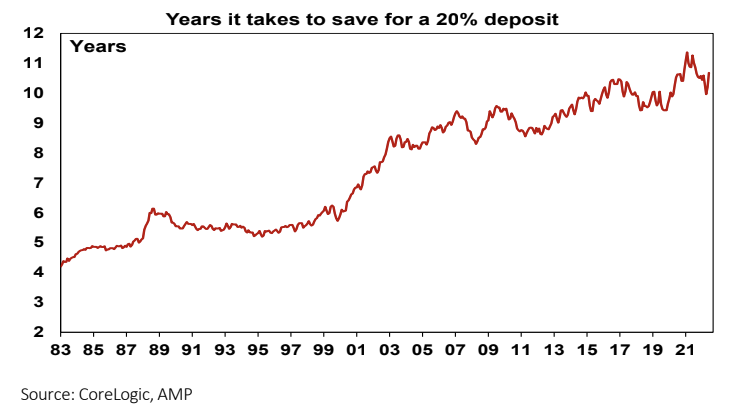

The first chart below shows the home ownership rate against two measures of housing affordability: the ratio of average home prices to average annual wages (in red); and the ratio of home prices to median household disposable income (green). The latter takes account of the rise in two income households, but data is not available before the 1980s.

But the message from both is that since the 1990s there has been significant rise in the ratio home prices relative to incomes. Prior to the mid 1990s average home prices ranged around two to six times annual wages but since then it’s steadily increased to around 14 times.

Similarly, the ratio of home prices to median household disposable income has blown out from around four times to eight times.

Disentangling their relative importance will be hard. The increase in the time it takes to save a deposit may also have accentuated the demographic factors referred to earlier – notably starting a family later in life – in delaying home ownership. Maybe the modest rise in home ownership in the last Census reflected the delayed start to family life.

Should we worry about falling home ownership?

What can be done to boost housing affordability?

Ideally, government policy should involve a multi-year plan encompassing local, state and federal governments. My shopping list on this front includes:

- Build more homes - relaxing land use rules, releasing land faster and speeding up approval processes, encourage build to rent affordable housing and greater public involvement in provision of social housing.

- Matching the level of immigration to the ability of the property market to supply housing. We have clearly failed to do this following reopening from the pandemic, and this is now evident in severe supply shortfalls.

- Encouraging greater decentralisation to regional Australia – the work from home phenomenon shows this is possible but it should be helped along with appropriate infrastructure and of course measures to boost regional housing supply.

- Tax reform including replacing stamp duty with land tax (to make it easier for empty nesters to downsize) and reducing the capital gains tax discount (to remove a distortion in favour of speculation)

- Policies that are less likely to be successful include: grants and concessions for first home buyers (as they just add to higher prices); and abolishing negative gearing which would just inject another distortion in the tax system and could adversely affect supply – although there is a case to cap excessive use of negative gearing tax benefits.

2 topics