Bank balance sheets expanding faster than expected with implications for liquidity needs

Yesterday, APRA released data for the banking system that revealed that balance sheets are growing very rapidly. Specifically, total bank resident loans/leases grew at a staggering +2.6% in the December quarter, while deposit growth remains very brisk, rising by +2.0% in the quarter. This puts the 6mth annualised pace of total system-wide bank lending growing at 8.3%, which is well above our steady-state assumptions around 5% pa.

The ongoing growth in deposits is important for the banking system’s demand for government bonds, known as Level 1 "high quality liquid assets" (HQLA1). Increases in deposits drive higher Net Cash Outflows (NCOs), which drives higher HQLA1 demand, all else being equal. Since balance-sheet growth is so robust, and new loans, by definition, create new deposits, rapid deposit growth should not be a surprise.

In Coolabah’s central case for forecasting the banking system’s HQLA1 demand, we have only assumed annual lending and deposit growth at 5% pa and 4% pa, respectively, which is materially below the current pace. Ongoing balance-sheet expansion at this rate implies higher HQLA1 demand than we have previously projected, although we have not adjusted our forecasts at this stage.

It is also noteworthy that the growth in balance sheets is being partly driven by the firmest business lending growth in years, which will presumably also translate into higher business deposits. Regulators require greater HQLA1 to be held in reserve against business, rather than retail, deposits, which is worth keeping an eye on...

How does HQLA1 demand change over time?

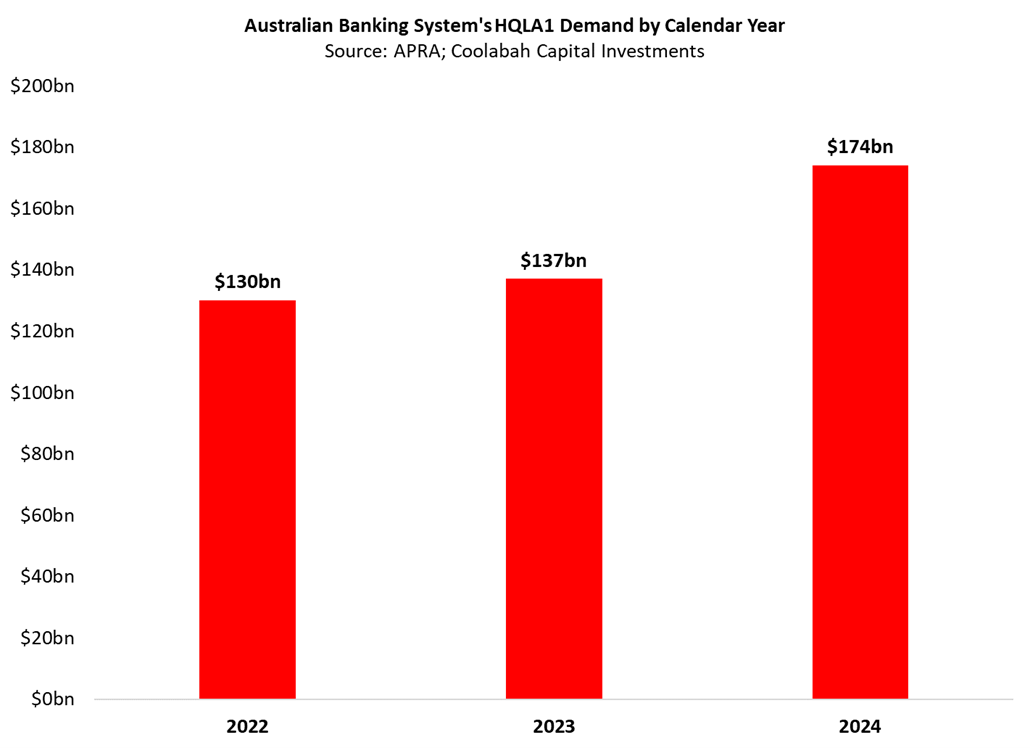

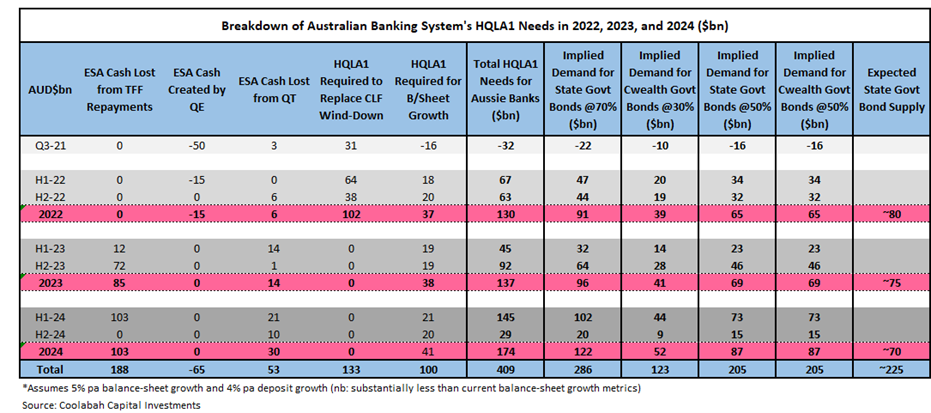

One question we have been asked is how the banking system’s HQLA1 demand changes in 2022 vs 2023 vs 2024. The chart below shows the banks’ annual HQLA1 demand, which is fairly evenly spread each year, although it does steadily climb. The table below shows the banks' HQLA1 demand broken-up by half-year and full calendar year, and by the individual demand drivers. The drivers are:

- RBA QE (reduces demand for HQLA as it creates excess cash that counts as HQLA1)

- CLF wind-down over 2022 (increases demand for HQLA)

- TFF repayments in 2023 and 2024 (increases demand for HQLA)

- Balance-sheet growth in 2022, 2023, and 2024 (increases demand for HQLA)

In the table above, we also include columns breaking down the demand across Commonwealth and State government bonds depending on the portfolio splits (eg, 30:70 and 50:50). Historically, banks have held 70% of their HQLA1 in State bonds, but we provide a more conservative scenario where they switch to 50:50.

Since Commonwealth bonds don't pay a positive spread above the swap rate, banks are unlikely to want to buy them unless the so-called bond basket arbitrage returns and offers positive returns. This arbitrage is not currently worthwhile, although perhaps that changes in the future. Even if it does, there are operational limits on how many futures contracts a balance sheet can carry as part of this trade, which significantly limits its scope (given limits to futures liquidity).

Sensitivities around our central case

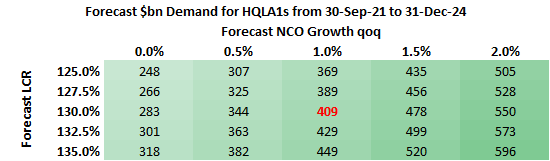

Finally, we have updated our matrix of HQLA1 demand according to assumed NCO growth and target LCRs. It is important to note that while banks might try to manage NCOs down, all agree that NCOs are very hard to control, and primarily driven by balance-sheet growth, given new loans create new deposits that then generates NCOs. Our base-case is 1% growth per quarter in NCOs, although the table below offers sensitivities around this in terms of estimating total HQLA1 demand in $ billions over the next 3 years. Another possibility is running lower LCRs, but given how volatile LCRs are (they can move 20-30 percentage points on individual days), banks don't like running buffers of less than 25-30% over the 100% regulatory minimum. Our reasonable range is between $283bn and $550bn of HQLA1 demand, with a mid-point of $409bn (previously $408bn). Strong balance-sheet growth would materially increase these numbers.

2 topics