Banks gouging taxpayers by arbitraging global liquidity rules...

Australia's banks are allowed to arbitrage global regulatory rules on best-practice liquidity requirements to maximise their returns on equity. This comes at a direct cost to taxpayers in the form of much higher contingent bail-out risks (given Aussie banks benefit from explicit government guarantees of their deposits and implicit guarantees of their bonds) and higher interest rates on government debt than would otherwise be the case. Having said that, APRA has repeatedly advised the banks (in writing) that they want them to phase out this loophole. Sadly, it appears that only ANZ has really listened...

Introduction

Aussie banks are exploiting unique Australian loopholes in global liquidity rules to lower their own cost of funds to the detriment of the interest repayments taxpayers make on government bonds. In this way, there is a direct transfer of wealth from taxpayers to bankers (and their shareholders). This note will show that there is nothing stopping APRA and the RBA from fixing this problem over the next year or two, as they have long said they would do.

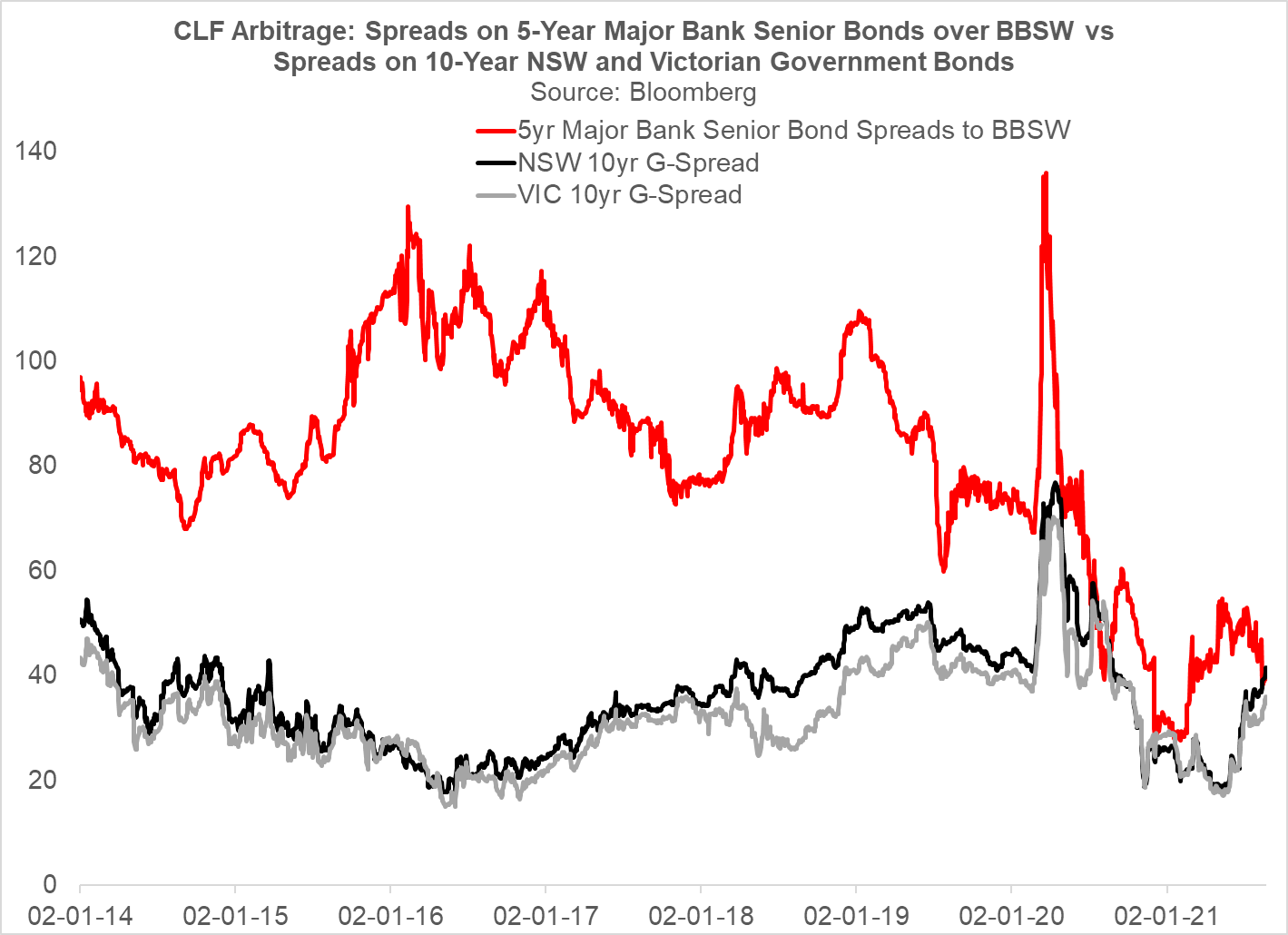

The former global head of interest-rate strategy at UBS, Matthew Johnson, last week published an impressively detailed analysis on this arbitrage of the global liquidity rules. Johnson finds that with the exception of ANZ, the major banks are holding $139 billion of their own internal home loans, other bank bonds, and bank- and non-bank-issued residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) instead of what they should be using as their emergency liquidity buffer, namely the global gold-standard of government bonds.

Around the world, banks hold government bonds as their core high-quality liquid asset (HQLA), which they can then transfer to their central bank as security (or collateral) and borrow against in an emergency. Importantly, developed countries like the US, UK, Canada and Europe do not allow banks to use their own internal loans, other banks' senior unsecured bonds, or bank-issued RMBS as HQLA for two obvious reasons:

- Accepting a bank's internal loans and other banks' senior bonds as HQLA loads the central bank up with enormous "wrong-way" credit risk (the central bank would strongly prefer to take vastly superior government bonds as collateral that are arms-length from the banks in question); and

- These securities, and a bank's internal loans, in particular, have a fraction of the liquidity of government bonds, which means that if a bank ever actually fails, and the central bank is stuck with their assets, they will be unlikely to dispose of them.

As Johnson explains, Australia is different because our government bond market used to be too small to provide banks with sufficient HQLA. So the RBA created the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF) as a novel back-stop, which today is worth about $139 billion.

Under the CLF, banks can use their own internal home loans and other banks' senior bonds and bank and non-bank issued RMBS as a substitute for government bonds.

This has two important commercial consequences. When a bank uses existing internal loans as a CLF asset, which they do 70%-80% of the time, they don't have to issue debt to raise money and then buy much lower-yielding government bonds.

Instead, they are using an existing asset, a home loan, which they have already funded, and which pays a return or yield that is multiples the interest rates they get on government bonds.

That's why banks use internal loans as the bulk (70% to 80%) of their assets in the CLF: it is a super high margin way to pretend they have HQLA.

The remainder of the CLF is made up of senior unsecured bank bonds and RMBS. Both these assets pay higher yields than government bonds---as they should because they have much higher risk and lower liquidity.

Westpac holding NAB senior unsecured bonds in its CLF portfolio (and vice-versa) also has the very convenient consequence of allowing the banks to artificially reduce their cost of capital. The fall-guy here is taxpayers because the banks would be otherwise holding government bonds, and reducing the interest rates taxpayers pay, were it not for the CLF.

Last week NAB issued a $2.75 billion senior bond that was 67% allocated to other banks. Most of this money would have come from the banks' CLF portfolios. Crucially, no other peer country in the world allows banks to use their illiquid internal loans and senior-unsecured securities as a substitute for HQLA in this way.

Now to their credit, APRA and the RBA have long signalled that the CLF will go to zero soon precisely because of the surge in the supply of government debt. APRA has written to the banks three times in the last 12 months warning that the CLF will disappear in the "foreseeable future":

"it would be reasonable to expect that if government securities outstanding continue to increase beyond 2021, the CLF may no longer be required in the foreseeable future"

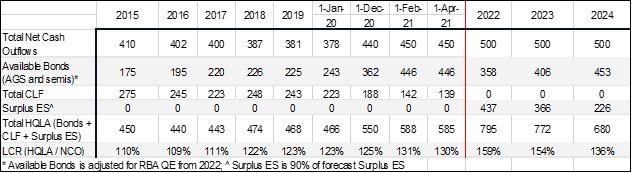

In his detailed research last week, Matt Johnson showed what everybody knows: given the explosion in both government debt and cash on deposit at the RBA (technically, the definition of HQLA includes (i) Commonwealth government bonds, (ii) State government bonds and (iiii) deposits at the RBA), APRA and the RBA should be zeroing the CLF.

The table below is from his research and is a little complex. But it basically shows that for 2022 there is no reason for Aussie banks to have any CLF, even after netting out the RBA's holdings of government bonds and allowing for an increase in their demand for liquidity via the assumption of $50 billion in extra Net Cash Outflows (NCOs).

.png)

Since most Aussie banks are not carrying much excess liquidity (CBA, NAB and Westpac's Liquidity Coverage Ratios (LCRs) are all around their lower-bound target of 125%), zeroing the CLF would force banks to issue bonds to raise money to then go out and buy government debt.

What the major banks will say...

It is at this point of the conversation the bankers (save ANZ) will start squealing. The bankers will say this is far too disruptive for their returns and profits. And they will argue that APRA should either not reduce the CLF because of this disruption, or if they do reduce it, they should do so over many years at a very, very slow pace. That's fair enough: they are trying to protect their profits.

There are two key problems with the bankers' complaints. The first is that one major bank, ANZ, has already taken APRA's advice at face value, and got well ahead of its peers in zeroing its CLF. ANZ is the great counter-factual: it shows what the other banks could do if they took APRA's written guidance seriously. ANZ's treasurer, Adrian Went, has publicly made two points very clear: there is more than enough government bonds for banks to hold instead of the CLF, and APRA has made its intent clear. And this is what ANZ has put into practice.

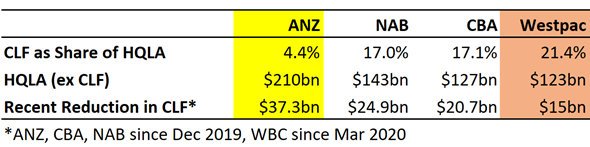

The table below shows the four major banks' CLF as a share of their total HQLA (including the CLF) in the first row. The second row shows the amounts of real HQLA (ie, ex the CLF) each bank holds. And the final row shows how much of the CLF the banks have reduced since 2019.

Whereas ANZ has slashed its CLF by a significant $37.3 billion, Westpac, a much larger bank, has only cut it by $15 billion. Whereas ANZ holds only 4.4% of its total HQLA (ie, HQLA plus CLF) in the form of the CLF, Westpac holds 21.4%. And whereas ANZ has $210 billion of government bonds, Westpac only owns $123 billion.

If I was to guess which banks have been buying one another's senior bonds and RMBS for their CLF, the obvious culprits are Westpac, NAB and CBA. I am pretty sure that ANZ is not engaging in this practice given how consistently it has focussed on moving the CLF to zero.

One question APRA and the RBA need to ask themselves is this: why are Aussie banks buying 5-year NAB senior bonds, as they did last week when the CLF is meant to be going to zero in the foreseeable future? Surely 5-years is beyond the foreseeable future?

Perhaps an even bigger question is what about the bankers' market disruption argument? Isn't it too much to ask our banks to zero the CLF over the next year or two? Won't they have to issue too much debt?

A key argument the banks make is that they will also be issuing debt to repay the RBA's Term Funding Facility. Aussie banks have had the huge commercial benefit of borrowing $188 billion under the TFF at the never-before-seen cost of just 0.1% annually. Compare that to the 1.8% interest rate the NSW government paid last week to borrow $1.5 billion!

So the TFF is due to be repaid in three years' time. Because of the immense benefit of the TFF, Aussie banks have not had to issue much comparatively expensive wholesale debt in recent years, as you will see below. The fiscal stimulus paid by Commonwealth and State governments, which they have funded by issuing new government debt, has also bequeathed another benefit to the banks: they have had a huge increase in their deposit inflows, which cost them virtually nothing (ie, they pay near-zero interest rates). This has further reduced their reliance on wholesale debt.

Modelling the debt issuance required to replace the CLF

So it is too much to ask the banks to replace the CLF with government bonds and repay the TFF over the next 3 years? Under APRA's regulatory rules, known as APS 210, the banking regulator clearly says (our emphasis):

An ADI must make every reasonable effort to manage its liquidity risk through its own balance sheet management before applying for a CLF for LCR purposes.

We know that ANZ has taken this to heart. The question is whether the other major banks can do the same thing comfortably. We've run the numbers on the required debt issuance, which are outlined below. We've been generous to the banks, and assume that APRA gives them 2 years, not 1 year, to get the CLF to zero. So we suppose the banks replace the CLF over FY22 and FY23. And then we assume they repay the TFF over FY23 and FY24.

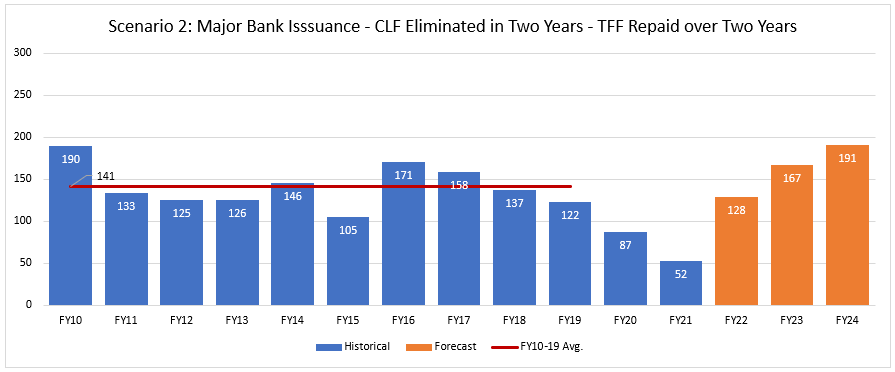

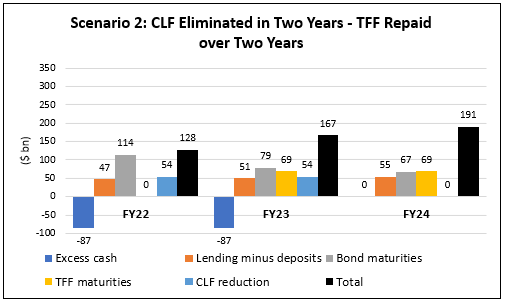

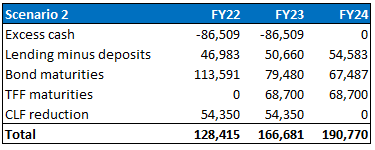

The first chart below shows that the four major banks have issued on average $141 billion of wholesale debt per year over the last 10 years. If they replace the CLF with government bonds over FY22 and FY23, and then also repay what they owe under the TFF over FY23 and FY24, we estimate they will issue:

- $128bn in FY22,

- $167bn in FY23, and

- $191bn in FY24.

This assumes that loan growth outpaces deposit growth by about 1.5% per year (or loan growth of 5.5% pa and deposit growth of 4.0% pa). Even the peak debt issuance in FY2024 of $191bn is the same as the $190bn the four majors issued in FY2010. No big deal.

So it would appear that CBA, NAB and Westpac are not complying with the intent of APS 210 (ie, they could reduce their CLFs and own more HQLA, but they are choosing not to). That is, they would prefer to keep the CLF around its current level to maximise their returns on equity and to reduce their own funding costs.

Importantly, the Basel Committee has some clear instructions here for APRA and the RBA. In this January 2013 paper, the Basel Committee wrote that for a country to use an alternative structure like the CLF instead of requiring banks to hold government bonds and deposits at the central bank, they:

Should be able to demonstrate that there is an insufficient supply of HQLA in its domestic currency, taking into account all relevant factors affecting the supply of, and demand for, such HQLA...

That Basel principle no longer applies to Australia: we have more than enough HQLA. So we will have to wait to see what APRA and the RBA do with the CLF in the period ahead.

A word on technical assumptions

Excess Cash

- The average cash and liquids balances held by the majors between 2016 and 2019 was $172.9bn.

- Most recent balance sheet publications detail spot cash and liquids balances totalling $311.2bn. CBA is the only major to provide the cash and liquids data for 30-Jun-21, following the full drawdown of the TFF.

- We have added the final TFF drawdown for the three remaining majors to their 31-Mar-21 cash and liquids balances, to arrive at the total majors' 30-Jun-21 spot balance of $345.9bn which provides the total excess of $173.0bn.

- Despite accounting for all ‘uses’ of cash, ‘sources’ such as the next three years earnings and asset sales are not included in this analysis.

- Although this was not the RBA’s intended use of TFF funds, 100% of TFF maturities are listed as a use of cash so we must include TFF drawdowns as sources. Final TFF drawdowns were added to WBC, NAB and ANZ 31-Mar-21 cash and liquids.

Bond Maturities

- Includes all the majors' scheduled maturities calculated at first call dates.

- Information sourced from Bloomberg.

CLF Reduction

- The majors’ outstanding CLF allowance is $108.7bn. Scenarios assume uniform reduction in CLF across the periods.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

2 topics