Bits, atoms and engines

Kasa Investment Partners

Perception is Reality

You may recall in Amazon, the Organism, I wrote about the three elements needed for motion: Intention, Energy and Autonomy. Here, the motion we are interested in is that of consumers. Specifically, why we are increasingly substituting physical experiences for digital ones. As most of us have both energy and autonomy, the focus will be on intention.

There is an interplay between the algorithm that is us and our environment. Our perceptions trigger chemical reactions within us, which then animate us into action. From Wikipedia:

Dopamine signals the perceived motivational prominence (i.e., the desirability or aversiveness) to an outcome, which in turn propels the organism’s behaviour toward or away from achieving that outcome.

Importantly, it is not the environment that causes a response, but our perception of what is there. Let’s use a simple example of misperceiving a rope for a snake. As explained in this article, our amygdala goes to work, endeavouring to hold the atoms that constitute ‘I’ together. It alerts our nervous system, which sets our body’s fear response into motion. Stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline are released. Our blood pressure and heart rate increase. We start breathing faster. Even our blood flow changes – away from our heart and into our limbs, making it easier to start throwing punches, or run for our life. Our body is preparing for fight-or-flight. And then … we realise it is a rope, the chemicals shift, fear transforms to relief, humour or even anger. The rope was always a rope, the inner algorithm was reacting to our perception.

A couple of side notes here. First, the view that there is an ‘I’ to begin with, is itself is a misperception, but that’s a story for another day. And second, the chemicals don’t only animate us in the moment, but may influence our future behaviour. We may find ourselves reaching for the phone to check messages, browse our social or shopping feed, or snack on videos & games. We may even be addicts without being aware of the addiction. To sense the strength of this force, try switching off your devices for forty-eight hours and observe what arises.

In the Manifestation Only School of Buddhism we learn of the three fields of perception: things-in-themselves, representation and mere-images. Continuing with the example, the rope is in the field of things-in-themselves. The snake is in the field of representation, a misperception of the rope. If we close our eyes and visualise a snake, or see it in our mind’s eye when reading in a book, or view it on a screen in a computer game, then we are in the field of mere-images.

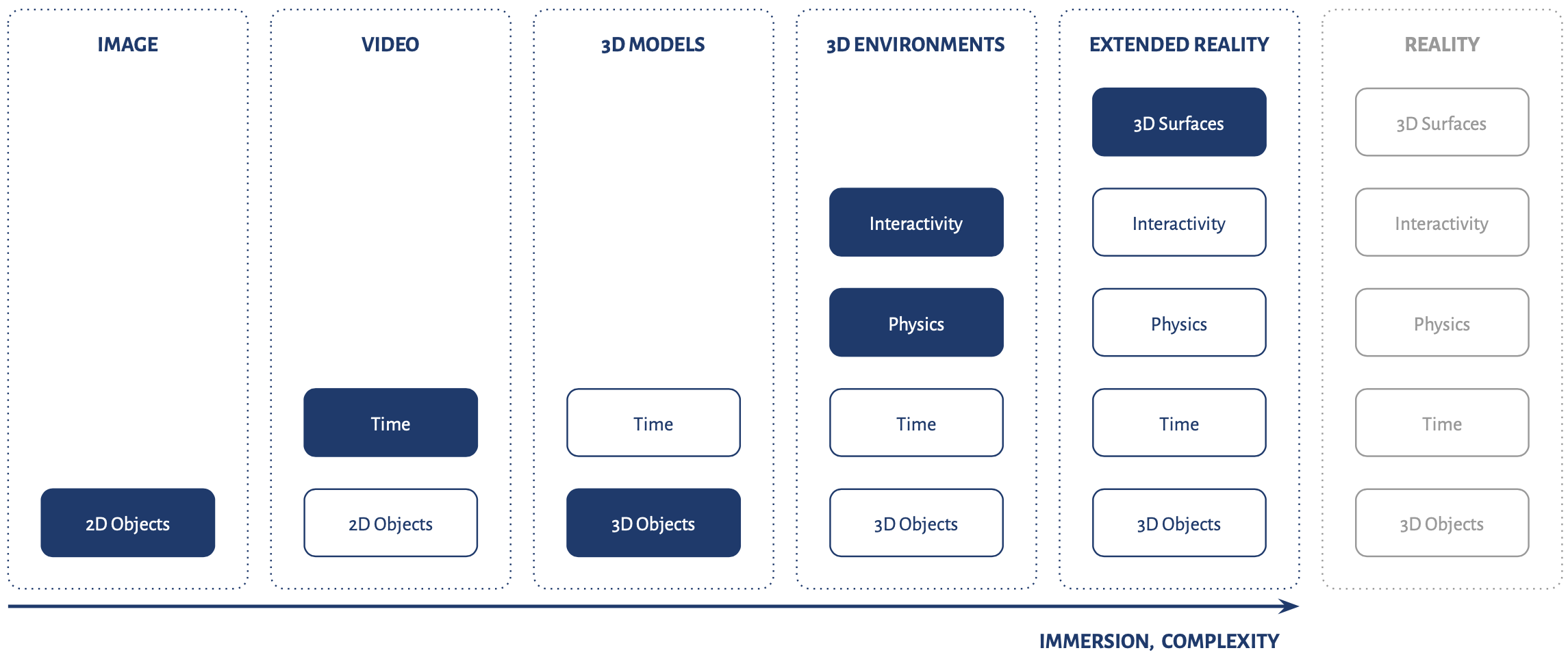

Our emotions result from our perceptions and so we can be in the field of mere-images and still experience an emotional journey. We may cry watching a heartfelt movie, or feel elated winning a computer game. There is of course a gap depending on how strongly we are drawn into the experience. We can think of immersion as a measure of this gap. In other words, the more immersive an experience, the less aware we are that it is not real and so the stronger our emotional response.

Immersion is a function of the interest we have in the object of our perception (how good is the story) and the medium of its transmission (what senses are being engaged). The digital world is allowing ever more creative experiences to emerge as accessibility to creatives is expanding. Computer algorithms are better matching these creations with our inner algorithm as more data is captured about our behaviour. And advances in hardware and software are engaging our senses in ever more immersive ways, as we move toward photorealistic, three dimensional, interactive experiences. Since our inner algorithm drives our behaviour, we seek, and so value, more immersive experiences. As the digital development curve is steeper than that of the physical world, we are increasingly finding ourselves substituting physical experiences for digital ones.

Bits and atoms

We can think of the building blocks of the physical world as atoms, and those of the digital world as bits. I’m not sure if this comparison is technically correct, but I find the distinction conceptually useful. We all have a basic understanding of atoms from our school eduction, so let’s touch on what we mean by bits. Here’s how Negroponte, the founder and Chairman of MIT’s Media Lab, describes bits in his 1995 book, Being Digital:

A bit has no colour, size or weight, and it can travel at the speed of light. It is the smallest atomic element in the DNA of information. It is a state of being, true or false, up or down, in or out, black or white. For practical purposes we consider a bit to be a 1 or a 0. The meaning of the 1 or the 0 is a separate matter.

In the early days of computing, a string of bits most commonly represented numerical information … we digitised more and more types of information like audio and video, rendering them into a similar reduction of 1s and 0s. Digitising a signal can be used to play back a seemingly perfect replica. In an audio CD, for example, the sound has been sampled 44.1 thousand times a second. The audio waveform (sound pressure level measured as voltage) is recorded as discrete numbers (themselves turned into bits). Those bit strings, when played back 44.1 thousand times a second, provide a continuous sounding rendition of the original music. The successive and discreet measures are so closely spaced in time that we cannot hear them as a staircase of separate sounds, but experience them as a continuous one.

The world of bits has responded to our seeking of ever more immersive experiences. By way of example today we may read, listen to or watch the story of Harry Potter any time and any place we like. What’s more, we can teleport into the Wizarding World of Harry Potter on a 2D surface such as a laptop or a phone, or on a 3D device such as a virtual reality headset. In this world we can interact with any object, including Harry himself, and invite our friends to join us. Unlike rereading a book or rewatching a movie, each visit to these interactive environments is unique, keeping us coming back for more. In many ways we are moving in the direction of Star Trek’s Holodeck, where the digital environment becomes indistinguishable from reality.

Engines

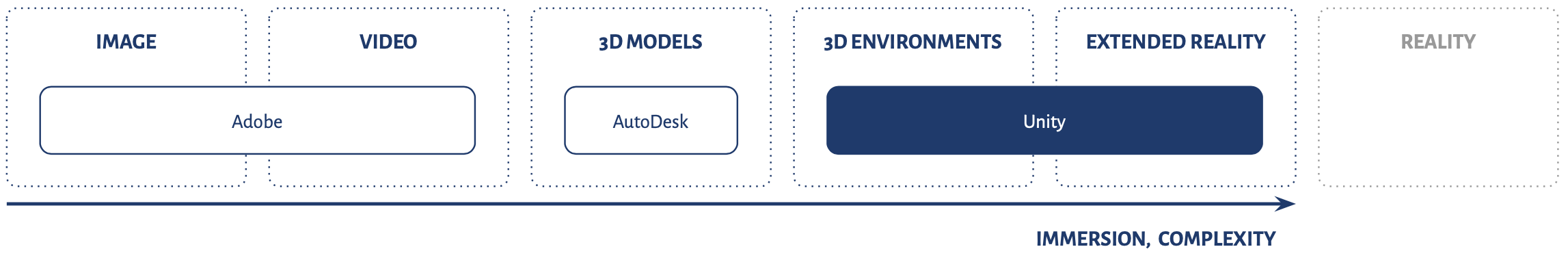

A game engine is a tool that enables creators to build interactive, digital experiences in real-time, and deploy them onto 2D and 3D surfaces. They manage ‘low-level’ computational tasks such as rendering, physics and audio, freeing up creators and developers for the higher-level aspects of creation and design.

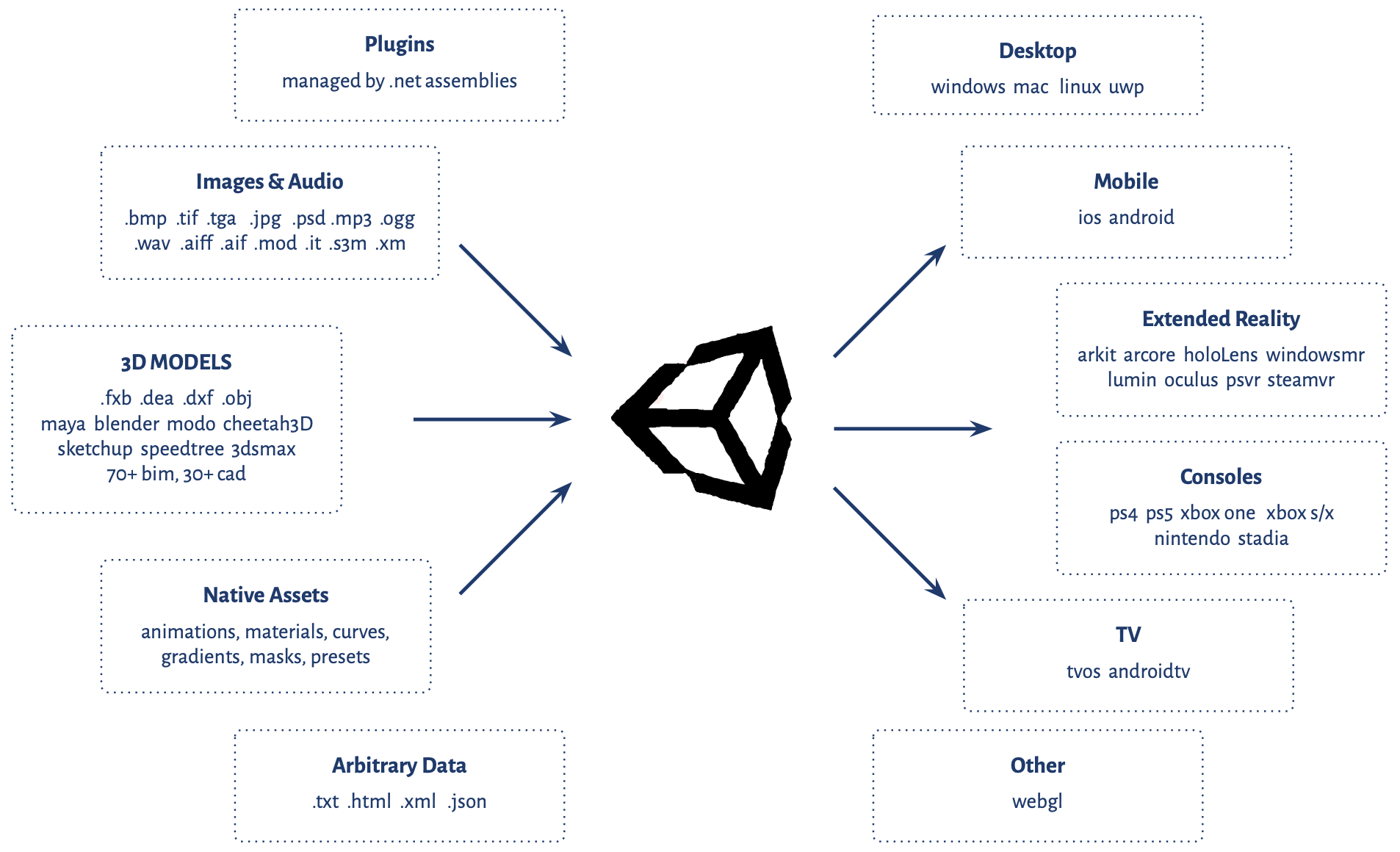

Unity is the world’s largest game engine. Here’s a lightly edited version of how the CEO, John Riccitiello, describes what Unity does:

If you go back in history, when somebody wanted to make a game, they’d have to hire an awful lot of engineers. Because when you’re going to make something that’s gonna be interactive, it’s got to have systems for rendering pixels on a screen, animation, processing sound, bouncing light around, basic UI and UX, physics for humans, physics to bounce a ball on the ground, and so many other systems. What Unity does is create an underlying technology base that allows all of those things to happen instantly and easily without having to write code – you just focus on the content.

The second thing we offer is an editor: like in a spreadsheet, you pull down, you click on something to create your content. You’re primarily using this editor to create your content, and also write some scripting language. And then Unity composites the code for over thirty platforms from Oculus to Hololens, Android to iOS, Xbox to PC to Mac. So we actually create the code. A content creator doesn’t need to do this over and over and over and over again. We provide the underlying technology and the systems that vastly accelerate the speed, and reduce the cost of interactive content creation.

In short, game engines are an integrated, real-time development environment enabling simplified and rapid development and deployment of interactive digital content.

from experiences to Efficiencies

Economies of scope are powerful phenomena that can simultaneously raise a company’s growth profile and widen its economic moat. From Investopedia:

An economy of scope means that the production of one good reduces the cost of producing another related good.

The textbook example is that of filling the belly of a passenger plane with cargo. A more modern example is integrating a camera into a mobile phone. In many ways, the linchpin of Apple’s business model is economies of scope, which people often refer to as Apple’s ecosystem.

Unity has been benefitting from economies of scope in a multitude of ways: extending to 3D surfaces, providing advertising services, and moving into adjacent services such as game tuning, multiplayer tools and content management. Here, the economy of scope we will focus on is the increased use of engines in industries other than gaming. This has been enabled by a series of advancements in areas such as processing power, networks speeds, and device proliferation. However, the fundamental gravitational force at work is the corporate pursuit of higher profits. Much like consumers seeking more immersive experiences, businesses are motivated by profits, which productivity improvements help achieve.

As identified by Negroponte, bits are weightless and able to move at the speed of light, making them essentially free and instantaneous when compared to atoms. These attributes create the possibility of step changes in productivity when activity is shifted from atoms to bits. Much like spreadsheets, the diversity of use cases makes it difficult to capture the full extent of what is taking shape. To get a sense of the new pockets of value that are emerging, let us look at a few examples, starting with some non-game engine ones.

The first example is that of the ideas in this article. They have been transmitted to you using bits because this is both cheaper and faster than using atoms. Second, the switching of a meeting from physical face-to-face to a video call. While this is not suited to all circumstances, there are many, particularly if travel is involved, where bits enable a step-change in cost and convenience. Finally, by substituting hand-drawn images with 3D computer graphics, Pixar revolutionised the animation industry.

Now turning to game engines, the photorealism now possible is causing a similar shift in the world of film. The Mandalorian, for example, was shot on a virtual set created by an engine. This not only removed the costs of working with atoms, but allowed greater artistic expression, as the created environments were not bound by the physical world. As these engines continue developing elements such as meta humans, entire photorealistic films will inevitably be made digitally, changing the economics of film making.

A Japanese robotics company is working on automating warehouse activity. They train AI to visually recognise objects for robots to pick and pack. This is no easy task, as the movement of the sun across warehouse windows alters lighting conditions. Using Unity, the company places a digital twin of the warehouse in a simulated environment, allowing AI training to be completed at a substantially lower cost and accelerating the time to market.

Let’s finish off with a lightly edited example by Riccitiello:

We recently released a product called Unity Reflect. It allows you to hold up and look through your Android or iOS device on a construction site, and the architect, who might be in head office thousand of miles away, is able to see what you see. She can check if a pipe is really where it should be, comparing it with the Building Information Model. This dramatically shortens the cycle from identifying to fixing a problem, which previously involved marking up a piece of paper, dropping it in a tube to go to the bottom of a construction site, to be couriered or flown to another location. There are fewer correction costs as problems are picked up earlier in the process.

The economies of scope that are manifesting in various forms around the core value proposition are extending the growth runway, and widening the economic moat of game engines. Unity’s response to this opportunity has been to integrate with more software, deploy on more platforms, release products that customise the engine to specific needs and simplify the editor to allow easier adoption.

CONCLUSION

I hope you have gained a greater appreciation of the fundamental forces driving the emergence of a large market for Unity, one that is underpinned by the advantages bits have over atoms, our thirst for immersion, and the corporate pursuit of profitability – as Marc Andreessen famously put it, ‘software is eating the world’.

In this note, we have only touched the surface of Unity’s investment case. There are important elements such as the winner-takes-all market structure, why Unity is the likely winner and notable risks that we haven’t covered. There are also responsible investment aspects to consider. While I do enjoy writing, I like researching even more, and so we’ll leave it there for now. If you would like to learn more, please reach out.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

5 topics

After an extensive career across RBA, Ausbil & Fidelity, Ali founded Kasa Investment Partners to solve the agency problems within the investment industry and derive a more direct relationship between the portfolio manager and the investor.

Expertise

After an extensive career across RBA, Ausbil & Fidelity, Ali founded Kasa Investment Partners to solve the agency problems within the investment industry and derive a more direct relationship between the portfolio manager and the investor.