Can the Aussie bank bounce last?

It would appear the death of banks as an investment has been greatly exaggerated. Australian banks have had a very strong period of recent outperformance since the vaccine inspired market rotation began in November 2020, helped along by rising bond yields and earnings upgrades not seen for several years.

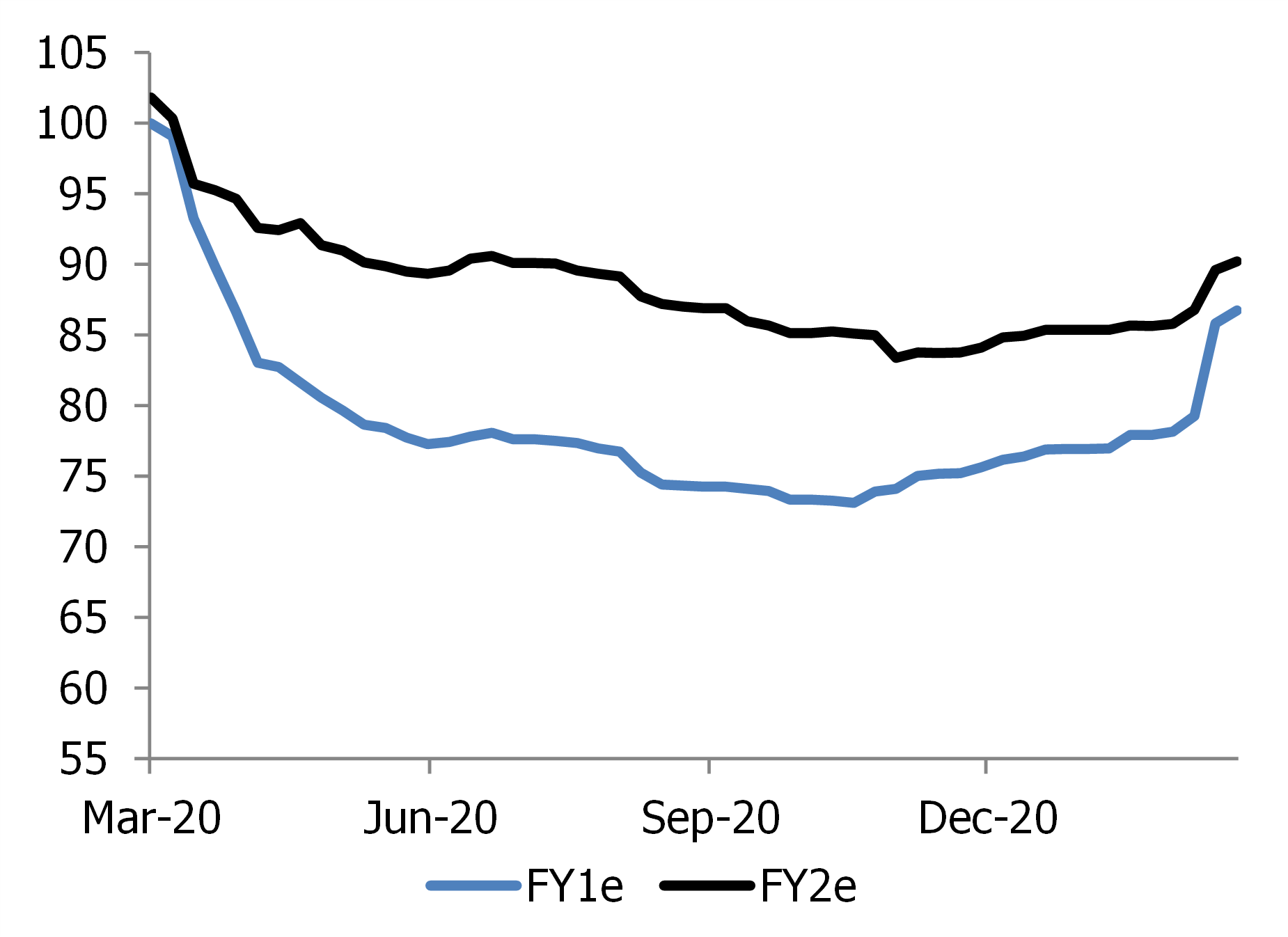

Earnings Revision Index for Australian Banks

Source: Alphinity

The sector has now outperformed the broader market by around 25% since that turn (to end March). This has placed the banks roughly back to where they were pre-Covid, despite lower earnings and lower dividends. The question is where to from here?

In our view the recipe is right for the positive trend to continue for some time driven by positive earnings revisions this year and a more favourable macro environment, topped off by better dividend potential and the possibility of capital management.

Until the recent turn in bank fortunes, the major Australian banks had largely struggled versus the broader market since 2015. The issues impacting the banks have been diverse, ranging from imposition of macro-prudential policies to the cooling of the housing market; increasing mortgage competition and pricing pressure; lower lending volumes; the Banking Royal Commission and subsequent fallout; falling interest rates impacting margins; inflated pay-out ratios putting dividends at risk; falling returns and rising capital requirements; a global pandemic leading to economic recession and question marks over credit quality. So that’s just to name a few!

In the wake of the pandemic, Australian banks traded well below book value on concerns around the potential size of loan losses as well as the flow on impact to capital levels. Concerns we shared. However, Australia’s response to the pandemic has seen the country fare exceptionally well from both a health and economic point of view. This has led to much lower concern around the credit quality of the banks. The flow on effect has been better capital positions, and now likely excess balance sheet provisions. Recent bank updates in February 2021 saw several banks start to release provisions early, leading to strong earnings upgrades across the sector, suggesting strong confidence from the banks about the outlook.

What are bank valuations telling us after the rally?

While the macro environment is more favourable for banks than we have seen for some time, they do need earnings drivers to push them forward from here.

Most absolute valuation measures are not as friendly after their recent run, although relative valuations remain fair for now.

Bank fully franked yields, although lower than historical, also remain relatively attractive compared to near zero deposit rates.

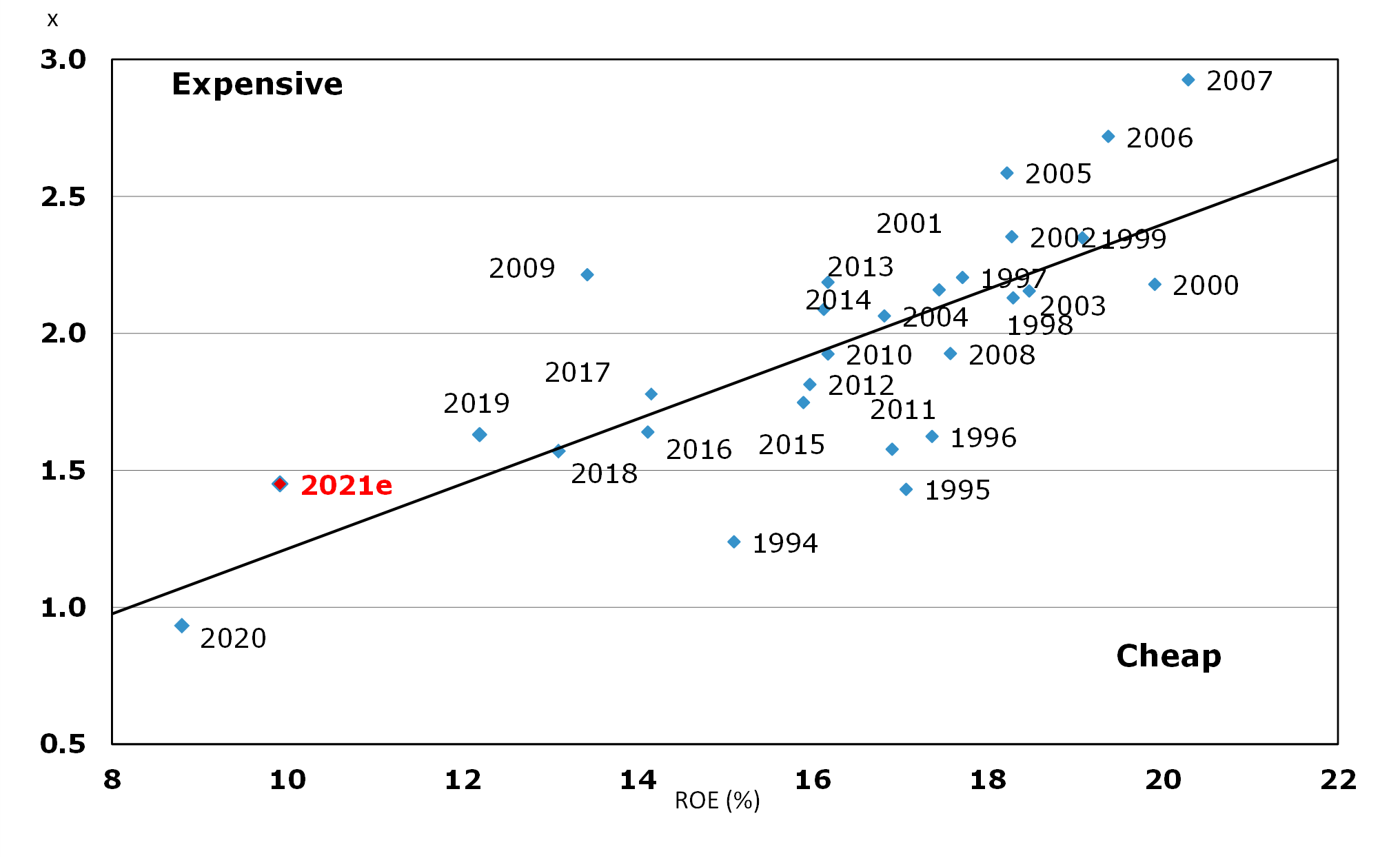

In times of crisis when dividends are in danger and capital at risk, the market often reverts back to Price to Book Value as the key valuation metric. A number of Australian major banks traded well below book value for long periods in 2020, which is historically unusual. They all trade well above now, and above historical trends when adjusted for current expected lower Return on Equity – perhaps not surprising given that the market is looking forward to better returns than currently expected. This may however put some cap on performance from here.

Major bank P/BV vs ROE

Source: Alphinity, UBS

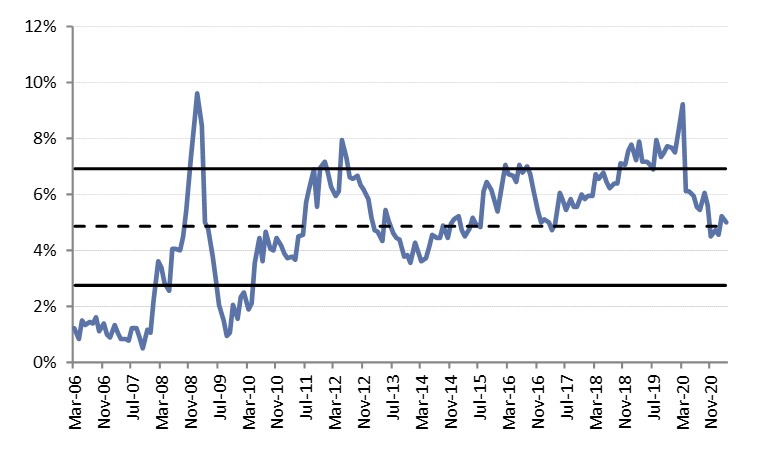

When times return to ‘normal’, dividend yields become a favourite valuation measure for banks. In response to Covid risks and regulator pressure, bank dividends were cut in 2020. Boards are understandably cautious in moving dividends back to previous levels quickly as uncertainty remains, and prior pay-out ratios were likely overinflated in many cases anyway. As such, absolute dividend yields for this year remain lower than historical levels. However, despite rising long bond yields, rates are still so low versus history that current dividend yields look relatively fair value by comparison. We also believe there is earnings upside and capital upside in 2021/22 that could lead to dividend upside surprise. With cash rates and deposit rates stuck near zero, bank dividend yields look even more attractive.

Gross dividend yield less 10 year bond rate - Banks

Source: Goldman Sachs

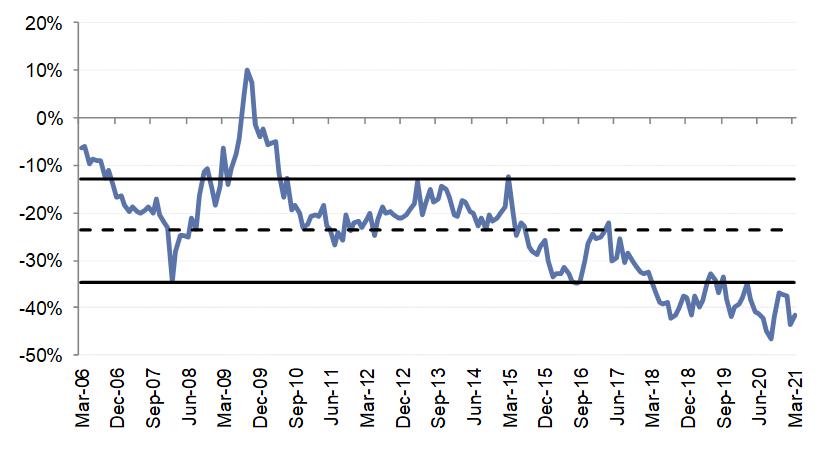

Price to Earnings (PE) is another valuation measure, however it is a bit distorted currently due to varying levels of bad and doubtful debts i.e. very high in FY20 with Covid and likely very low in FY21 as we emerge better. Nonetheless on a historical basis banks look a bit expensive on absolute PE. Looking at pre-provision profits is one way to smooth out the loan loss volatility. On that measure banks look even more expensive on an absolute basis. However, given the elevated PE of the whole market, comparing bank PE’s relative to the Industrials ex Financials Index, they look quite attractive.

Price to EPS – Banks relative to ASX 200 Industrials ex Financials

Source: Goldman Sachs

Loan loss risk turning into a positive

The major concern for banks in 2020 was the unknown level of loan losses the banks would have to wear through the Covid induced recession. The banks took large hits to earnings as they raised provisions in anticipation (actual losses were delayed by policies and actions designed to ensure companies and individuals stayed afloat giving time to adapt).

Initially given the size of the downturn and estimates of unemployment we felt the increased losses could potentially be much bigger than the level of increased provisioning taken. Furthermore, you typically see most actual losses appear up to 12-18 months after an economic shock. However, the environment has played out materially better for a number of reasons:

- Both monetary and fiscal stimulus have been multiples larger than expected.

- The design of fiscal stimulus e.g. JobKeeper, has ensured much lower unemployment and an unprecedented amount of time to prepare for companies and individuals.

- By geographical luck and a strong stance taken by governments, we have navigated the pandemic better than most to date and the economy has responded well. Confidence is high.

- Many companies went into the crisis well-funded and relatively lowly geared meaning they have weathered the bumps better than historically and have been able to keep people employed.

- Technology has meant much of the economy could continue to work and function and adapt relative to past downturns.

There are still hurdles to navigate as stimulus rolls off and certain schemes end or change, however the starting point is much better than expected and it is unlikely, having thrown this much at the problem, the government is going to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory – we now know their playbook.

The banks have however provided for much tougher times. As such we would expect the major banks to release excess provisions over time that are no longer required. Those releases boost profits. Profits help capital and dividends.

We have already seen several banks write back some of the provisions in the February 2021 reporting season, however this is early days. The numbers left are quite large.

If we assume provisions in 2019 (i.e. pre-pandemic) were ‘normal’, we can estimate the excess provisions the banks potentially have. This won’t all come back at once as bank boards will want to see the after-effects of Covid that could play out for a number of years to come. What it does is ensure profits have a decent head start each period – a tailwind banks haven’t had for some time.

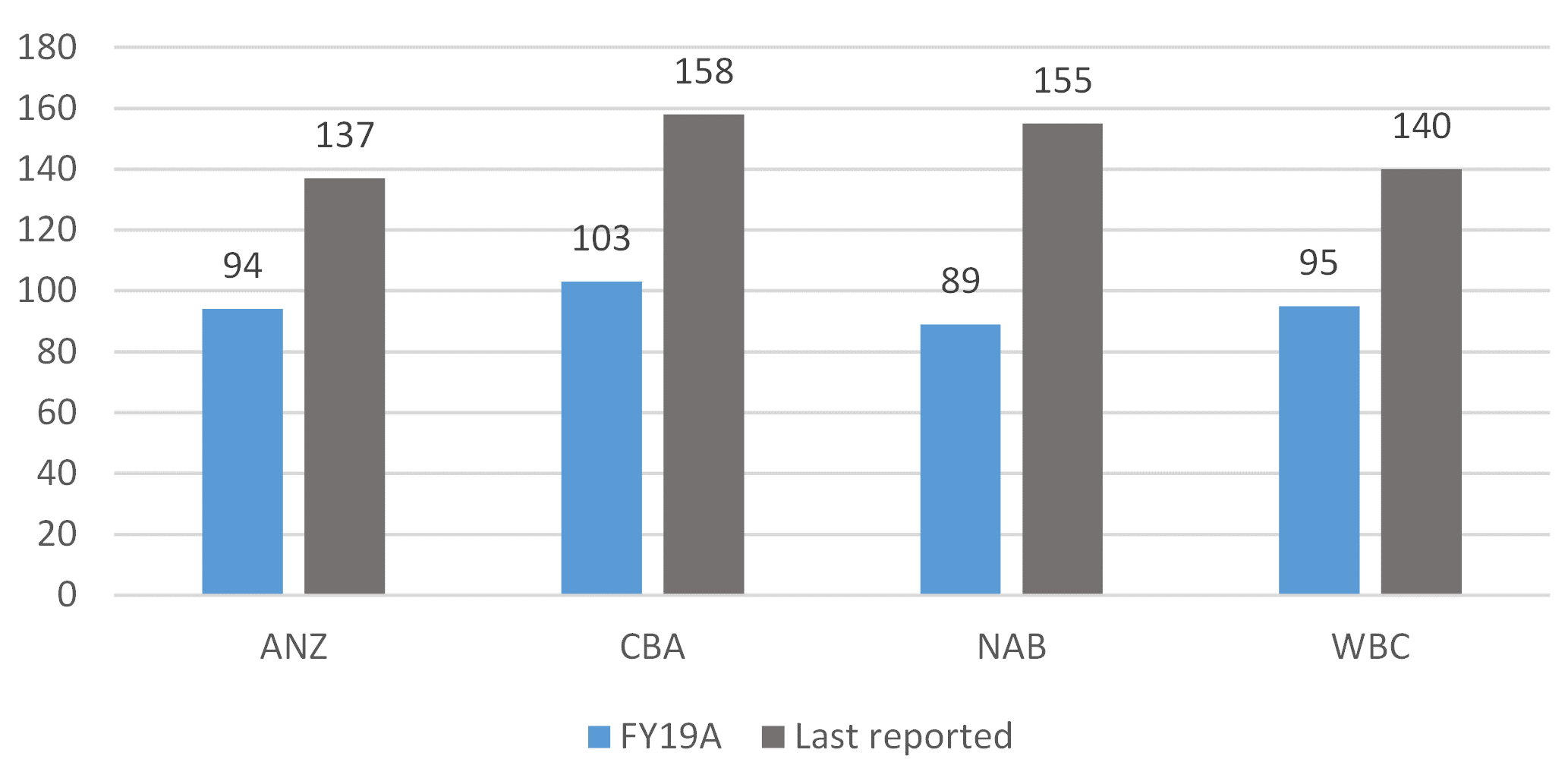

The chart below shows level of collective provision versus credit risk weighted assets per bank (this represents the general provision banks put aside to fund any future loan losses). You can see the large increase now relative to 2019.

Provision – CP/CRWA (bp)

Source: Alphinity, Citi, CS

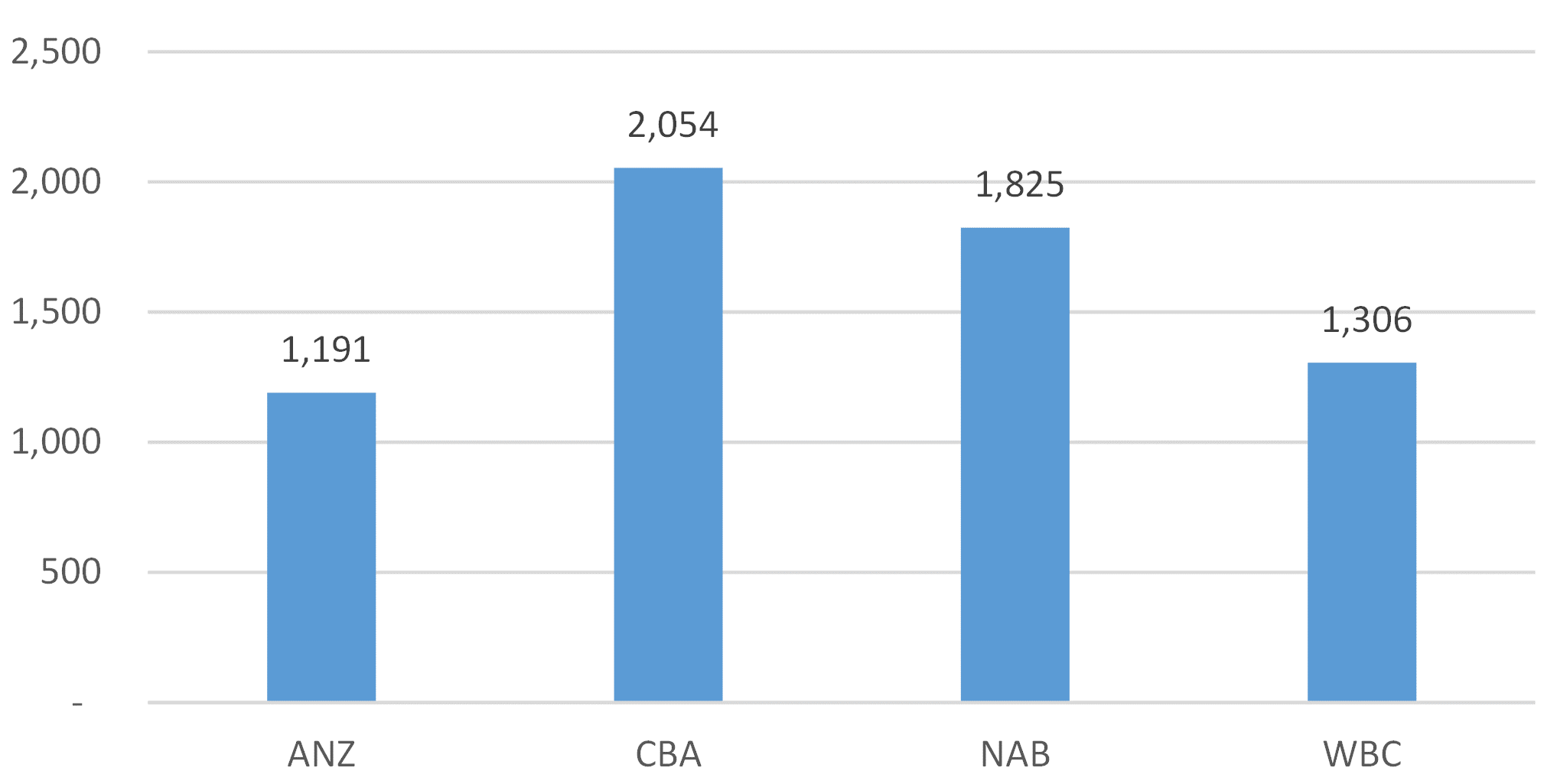

If we assume (all else equal) that the banks revert to 2019 levels of CBA (being the highest at the time), the estimated excess provisions to come back over time are shown in the chart below per bank. To put this in context, for CBA this is 15-16% of one years’ pre provision profits before tax (NAB ~19%, WBC, ~13% ANZ ~12%). A decent tailwind for earnings.

Estimated excess vs FY19 ($m)

Source: Alphinity, Citi, CS

Capital management is coming

The banks have spent the better part of the last decade playing catch up on ever rising capital requirements post the Global Financial Crisis. This has pressured returns, increased share number count and impacted share prices.

A combination of asset sales by the banks, capital raisings, lower growth and dividend cuts has seen all the majors move into a position of excess capital. A better economic environment and improved credit quality and earnings will all add to that dynamic going forward. Once boards are confident on the sustainability of the better outlook, they will not want to sit on excess capital. As such we are likely to see capital management over the next 12-24 months.

Capital management could take the form of share buy-backs (most likely and most effective in our view), special dividends, or partially used over a longer period to increase ordinary dividends.

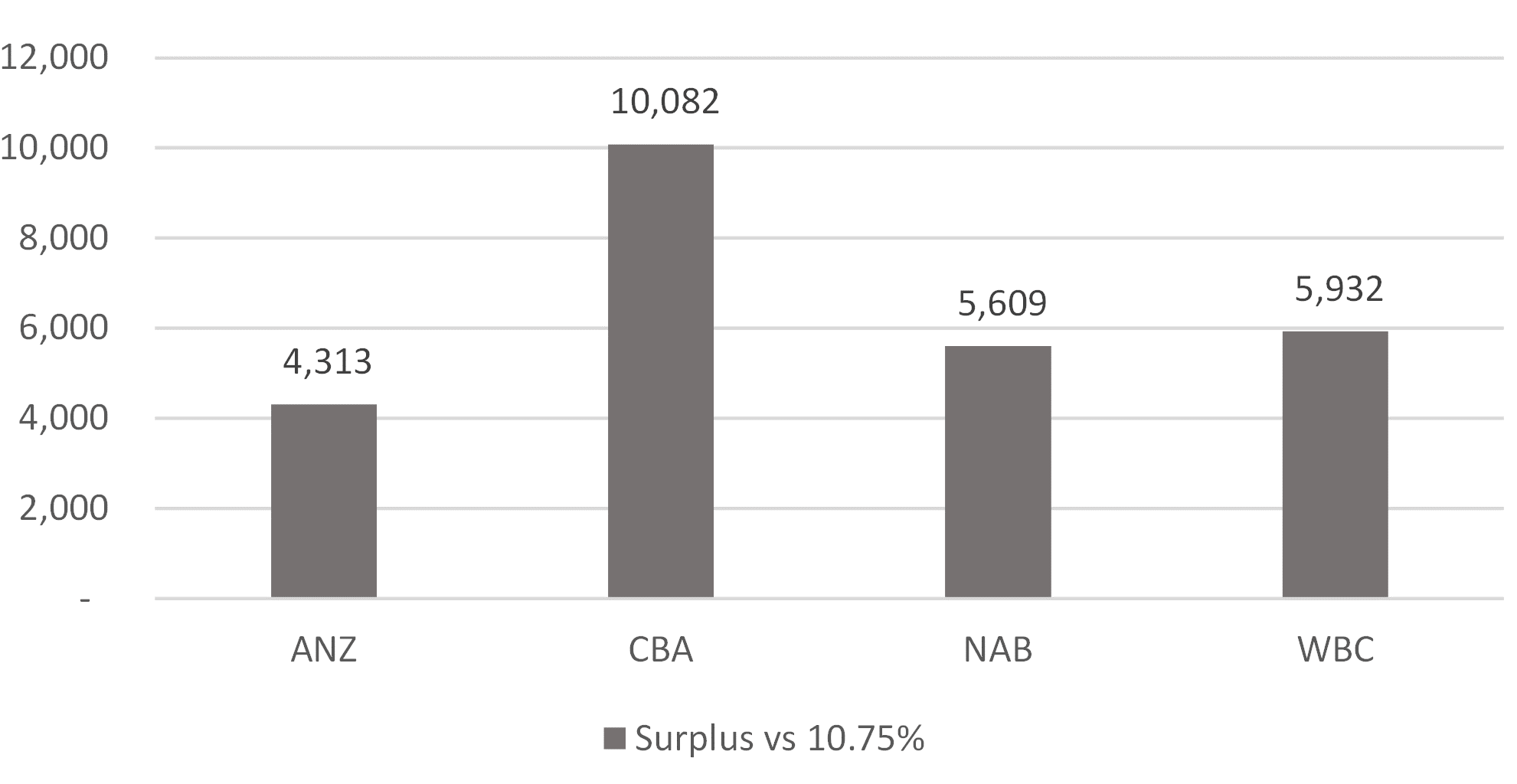

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is yet to fully finalise capital requirements, but using what we know currently and assuming banks want some buffer to the current 10.5% requirement, (and also noting that the market was pretty clear they didn’t want banks to dip below the 10.5% level even in a crisis), we can estimate roughly how much excess currently exists per bank as seen in the chart below. Clearly CBA has the most to come back. Banks who have raised capital in the last year (NAB and WBC) or have more operational and regulatory issues (WBC) may be more cautious about giving it back quickly. Should lending growth really come back in a big way then some capital will need to be retained to fund that.

Capital surplus vs 10.75% ($m)

Source: Alphinity, Credit Suisse

Other operating tailwinds building, it is still tough for banks

The operating environment for major banks however continues to remain mixed, although even that is an improvement on recent times. Mortgage volumes are showing some life, net interest margins are ‘less bad’ as funding costs improve, asset prices are up, and technology and digitisation will ultimately improve efficiency for banks (although getting absolute costs down is largely proving elusive for now). On the other hand, competition is fierce amongst the majors, interest rates remain very low, businesses aren’t borrowing, and technology is providing a platform for smaller start-ups to attack bank profit pools cheaply.

- We all know that the housing market in a number of major cities is booming. Mortgage application volumes are sky-high and over time that will flow into lending. Note however that low interest rates also mean record paydown of mortgages so net growth will be a lot lower (single digits), but still up from the 2-3% seen prior. We see upside surprise potential here.

- Business lending however appears to still be stuck in the doldrums. Companies are largely well funded and have spare capacity. They have plenty of cash on deposit to draw on first.

- Bank net interest margins (NIM) remain under pressure from low interest rates, although have found some near-term reprieve from lower funding costs. As interest rates have fallen, that has led to lower mortgage rates. However, banks use deposits as a major funding source for mortgages and they have a lower bound of zero (at least for now in Australia). In other words, you can only cut deposit rates so much before the margin between what you have to pay in deposits and what you get in mortgages is squeezed. On top of that any excess funds you have, plus capital, get invested in cash or shorter-term bonds and you get a lower return. There is some three-five year hedging but every day those hedges roll off further. We would need to see three-five year bond yields rise materially from here to offset, however yield curve suppression at the shorter end is preventing that from happening.

- Better funding costs and mix are now helping bank margins (less bad). Not only can the banks borrow from the taxpayer at close to zero for a time, the deluge of deposits has seen the banks be able to re-price term deposit rates well below what was thought possible. Furthermore, this has seen a positive mix shift. As term deposits have gone close to zero, many deposit holders have decided against tying their money up and have moved to a transaction account at zero interest, effectively re-pricing deposits down further. While we are close to the limit, this recent help has still to fully average through the book.

Positioning: macro and micro suggest stay overweight

With likely upgrades continuing and operating tailwinds now providing some offsets to the headwinds of the last few years, topped off with potential capital management and valuations being largely acceptable, fundamentals seem to suggest staying overweight for now despite the recent strong run. Of course, fundamentals are one thing, but banks do not trade in a vacuum. Macro forces play a major role for bank investments, not just on earnings but on bank sentiment amongst investors as well.

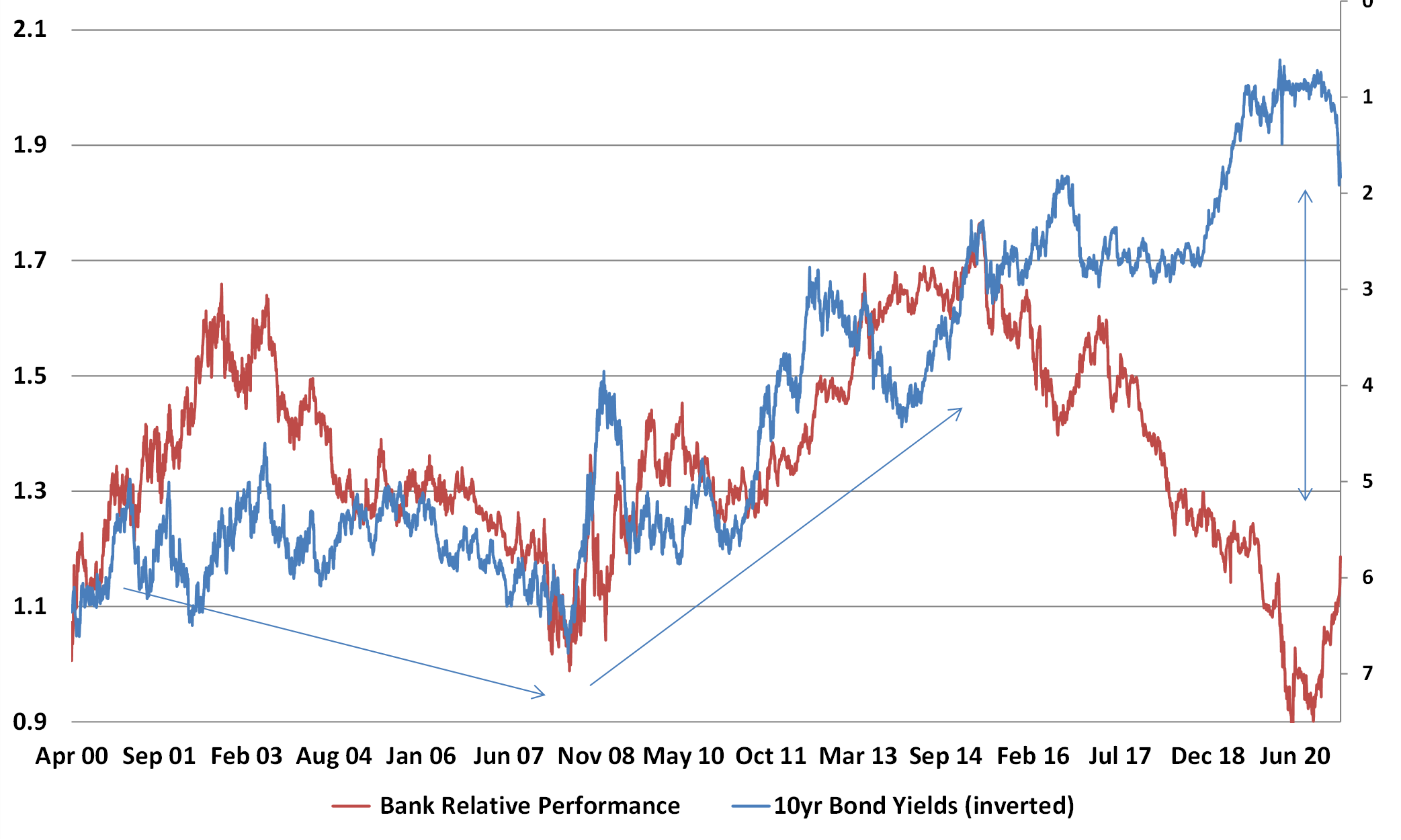

Bond yields in particular are a big swing factor in sentiment towards financials. As a broad rule of thumb globally, a steeper yield curve sees money flow towards bank stocks (and financials in general). Typically, a steeper yield curve indicates an environment that is easier for financials to make money (and a better economic environment to operate in). In Australia, however, the relationship historically has actually been the inverse of this until around 2015.

Australian banks do not have the same earnings kick from a steepening yield curve that you see in some offshore markets like the US (different lending and funding structures).

Also bank dividend yields were often seen as a close proxy to bond yields and as such moved inversely i.e. as bond yields fell, bank yields looked more attractive and as bond yields rose, they looked less attractive. However, with cash rates at close to zero we are in a different world, and Australian banks have for now moved into a synchronous relationship with bond yields and global financials. As bond yields rise, banks are outperforming. A rising bond yield is seen as indicating a better economic outlook and potential future interest rate rises, all positives outweighing any concerns about yield comparisons. With the yield curve likely to remain here or continue to steepen for some time as the world improves economically and all the stimulus comes through, this should help banks continue to do well.

As such the macro and micro are pointing in the same direction suggesting being overweight the banks for now.

Bank performance vs bond yields

Source: Alphinity, Bloomberg

Want to learn more?

To find out more, please visit our website, or use the contact form below.

1 topic

5 stocks mentioned