Careful what you wish for 'cause you might just get it

Global Macro

Ah currencies. Just how important are they? Many pretend to understand, but are quickly confused. Even US presidents. I particularly like this exchange between President Nixon and his Chief of Staff, Haldeman:

Oh, how times change. By 1985 the US was orchestrating the Plaza Accord to engineer a 50% appreciation of the Yen!

Trump remembers Japan in the 80’s. Indeed, I think all his economic beliefs were formed in the 80’s. And he now thinks China is the new Japan. And he doesn’t like what is happening with their currency.

“China’s currency is dropping like a rock”, he complained on CNBC last month.

Is he right?

Well he appears to be. Since April, the USD has strengthened over 9% against the Chinese Renminbi.

Indeed, it has been a very quick move. So I think it is fair to say Trump is right in his description. But is he right to complain? Ah, that is a much more complicated question; perhaps too complicated for even some presidents I dare say. But perhaps allow me to be brave enough to have a stab. (For those short of time, jump straight to the Market outlook).

Firstly, does it matter? As an Aussie might say, “Bloody oath it matters!” It is the key reason why Australia has enjoyed the longest period of growth without a recession in recorded history.

Is that too big a statement? No. Australia has performed three “global recession escapes” in the last 30 years, and in all three the currency did a lot of the heavy lifting (or falling as it was).

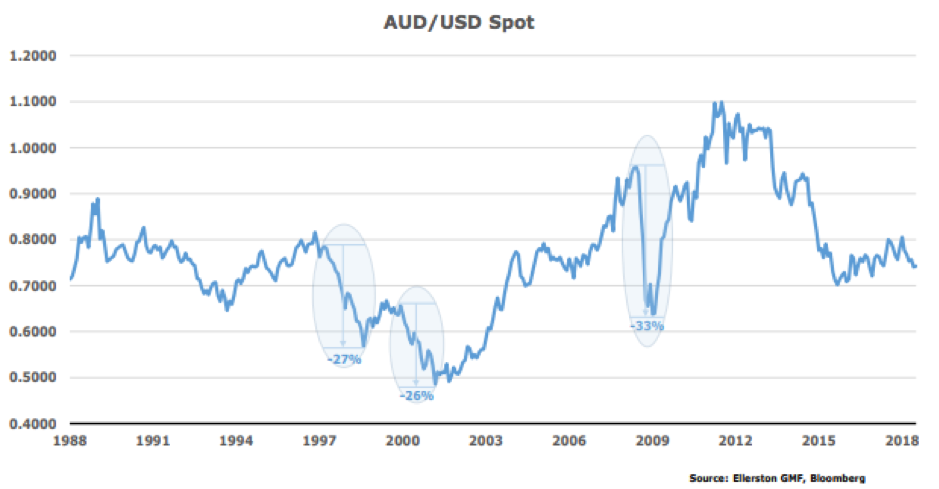

The three episodes were the Asian crisis in 1997/8, the Dot Com recession in 2000/2001 and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008/9. In each instance the AUD fell 26 to 33 per cent.

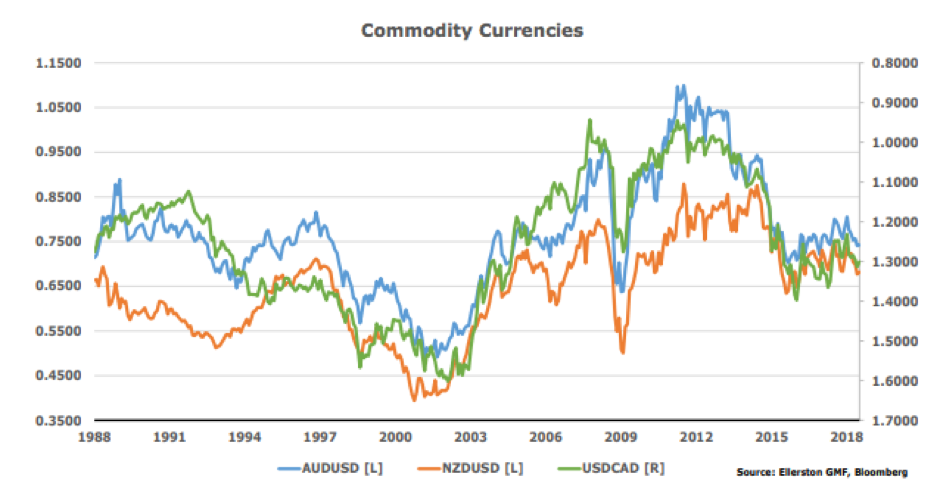

Didn’t that happen elsewhere? Well actually yes. Other commodity currencies followed a similar path.

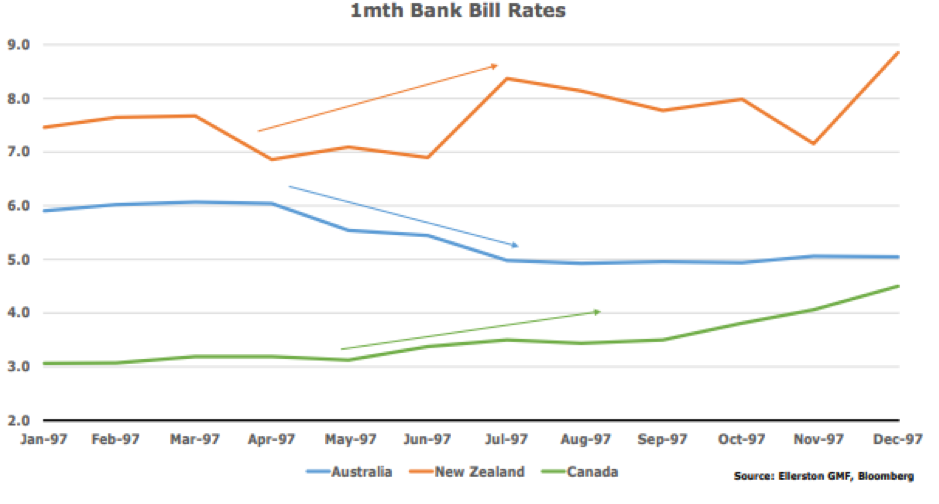

The difference was the RBA accommodated the weaker currency. Particularly in 1997. That was a watershed moment. Conventional wisdom at the time was that when the currency fell, the cost of imports went up, hence inflation would rise and the central bank would need to raise rates to ensure that inflation did not become entrenched.

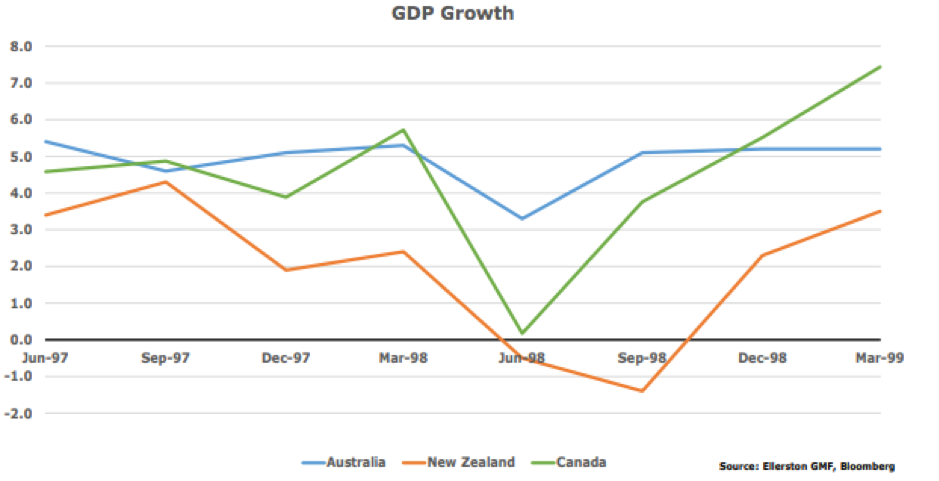

That was the reaction of both Canada and NZ, with both increasing interest rates in 1997. But the Reserve Bank of Australia cut rates. The consequences were seen the following year. Australian growth dipped trivially. Canada and NZ skirted with/had a recession.

The RBA at the time had taken the rather revolutionary view that inflation would prove transitory, and that they should support growth by keeping interest rates stable, or indeed lowering them. It was this break from the one-dimensional behaviour of the past that was most instrumental in delivering a record expansion for Australia. Now Glenn Stevens might argue that it was the anchoring of inflation expectations in the prior 5 years that allowed them to pursue that strategy. That is true. But so it was for the other countries. No, the real epiphany was the realisation of what was possible with inflation tamed. Like Laird Hamilton using jet skis to open up the world of big wave surfing, the RBA used stable inflation expectations to bring the exchange rate into the policy tool chest.

Of course it is not the only reason Australia has enjoyed a 27-year expansion. An aggressive central bank when the need arose and a well-timed aggressive fiscal stimulus in the GFC also played significant roles. But the currency was always allowed to “do its part”. Indeed, it is this “part” we capture today in our financial conditions indices (FCIs).

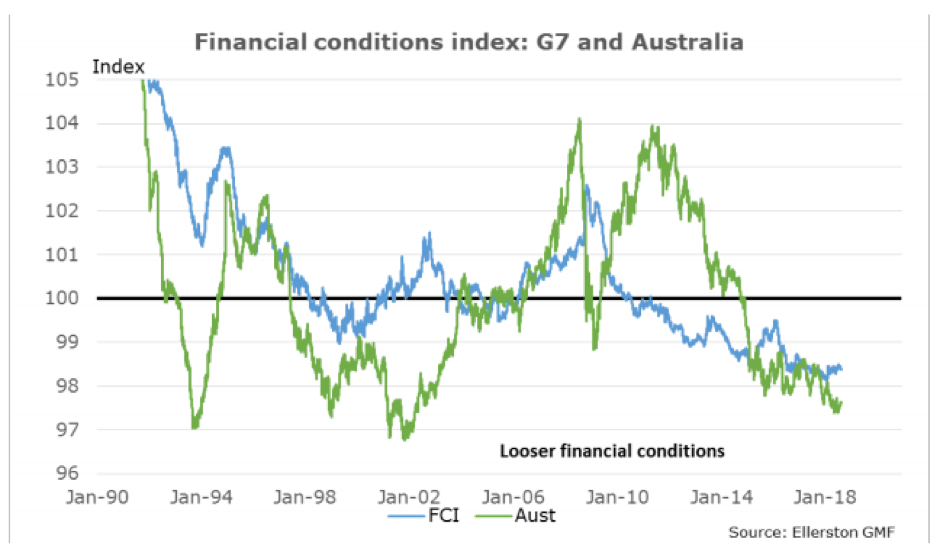

So look at what happened to Australia’s FCI in 1997. It loosened (fell) a lot more than the average country (G7 is the 7 largest economies in the world). By easing when the currency was also falling, the FCI fell from 101.2 to 97.23. That’s equivalent to financial conditions moving from a 1% headwind to growth to a 3% boost to growth over the next 9-12 months. And again in 2001, a 2% boost to growth. And in the financial crisis, moving from a 4% headwind to a 1% boost. By anchoring inflation expectations, the RBA could let the currency “do its part”, and it fully embraced the support!

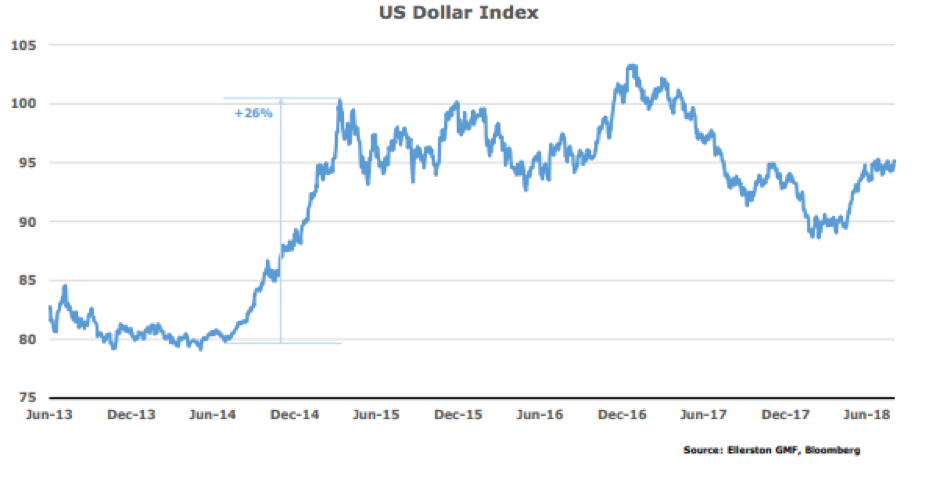

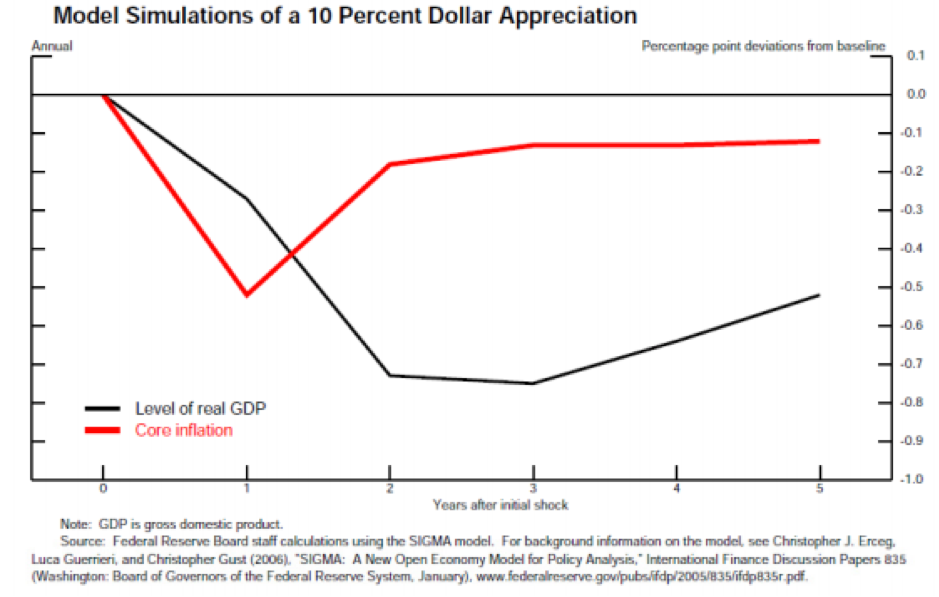

We calculate the FCI for numerous countries. The importance of the currency varies from economy to economy, because the amount each country imports and exports varies across countries. And also the importance of the currency depends on foreign debt levels and industry composition. So our FCIs need to calibrate for how important the currency is in each economy. At my prior abode, I relied on the Fed for my FCI. My mistake. In 2014/15 the USD appreciated some 25%.

But, given the lower share of exports in the US economy, I (and the Fed) deemed the impact as limited.

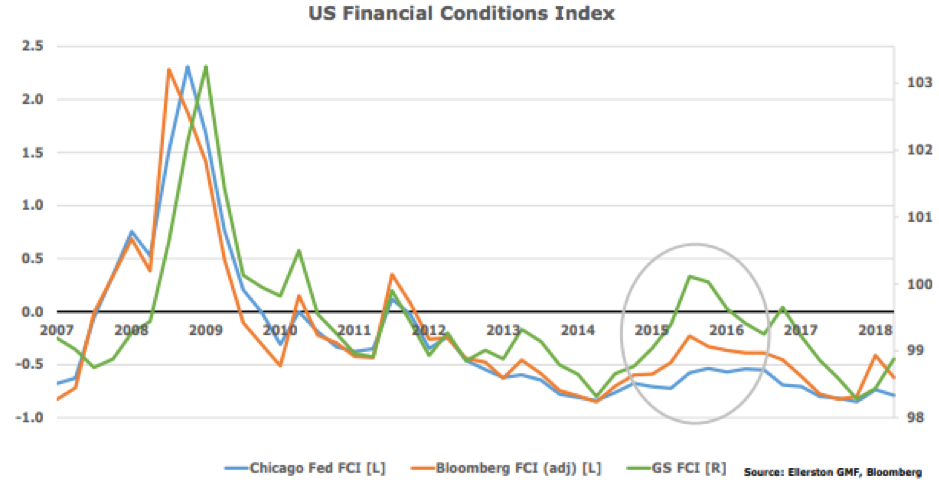

On the chart, the blue line below shows how much the Fed’s financial conditions index tightened in 2015. Not much. We find a well calibrated financial conditions index forecasts the economy with about a 9-month lead. But note I say well calibrated. That is the art. There are many FCIs around, particularly for the US economy. Also on the chart, I show the Bloomberg FCI and Goldman FCI. The measured tightening varied considerably.

How wrong I was to follow the Fed! Indeed, Stanley Fischer opined in July 2015 that new Fed research showed the currency impact was the equivalent of a 1.75% hit to GDP growth over 2 years! Hence the Fed only hiked once in 2015, when at the start of the year they were forecasting 4 hikes…

So it is clearly important.

What did Tim’s Toohey’s FCI say? Well, he hadn’t built it for me then, but looking back we can see it was also worth a 1.75% detraction from GDP.

And so when someone asks does the move in the currency matter, we say it depends. It depends on what everything else is doing. This is where the FCI is so useful. It not only captures everything else but if weighted correctly, it is a crystal ball to growth 9 months ahead. And that is the key. Weighted correctly. The weights do evolve, and Tim Toohey has been building these indices for well over 20 years now. I believe they are the best available.

Market Outlook

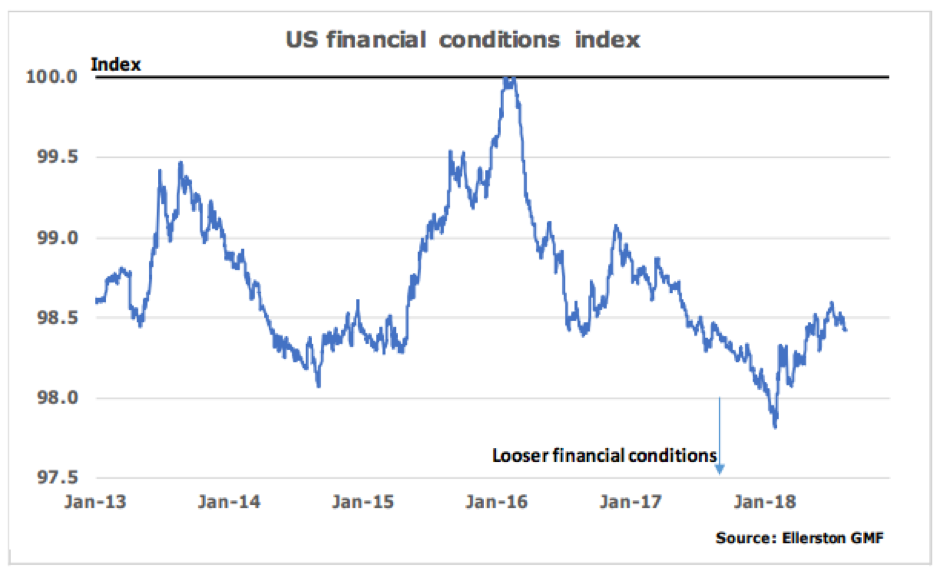

So does the current move in the CNY matter? Well not for the US. (See chart above)

And it would seem not for China, with financial conditions simply returning to where they were 12 months ago.

Indeed for China, the positive impact of a weaker currency has offset the negative impact of their falling stock market. Mmm, hasn’t the falling stock market got something to do with tariffs? Doesn’t it make sense for the Chinese currency to weaken to support the economy - for the currency to “do its part”? The RBA would certainly think so.

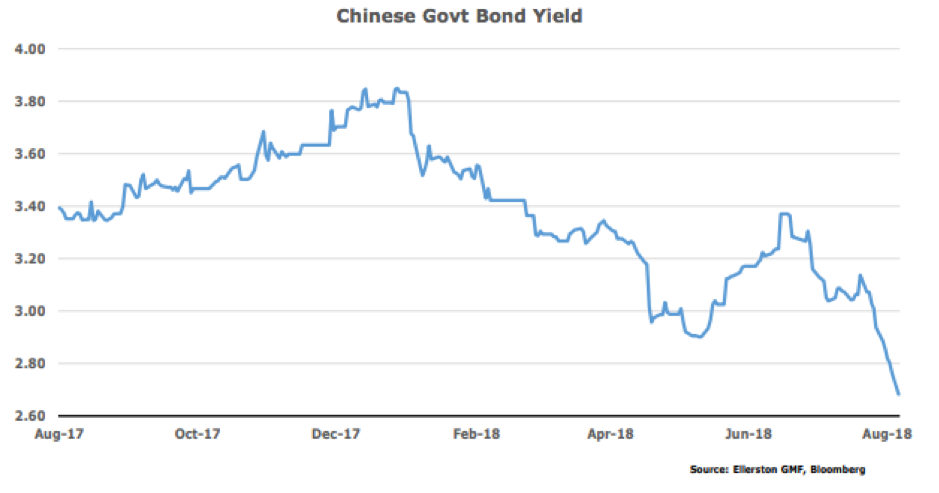

To be fair, the Chinese stock market started falling well before the tariff war broke out. Up until June, the Chinese had been engineering a slowdown. In particular, they had been focussed on reducing the “shadow banking” that was overstimulating the housing market and risky investment in general. As the tariff war has escalated, they have now fully reversed course, cutting interest rates, easing credit and easing fiscal policy.

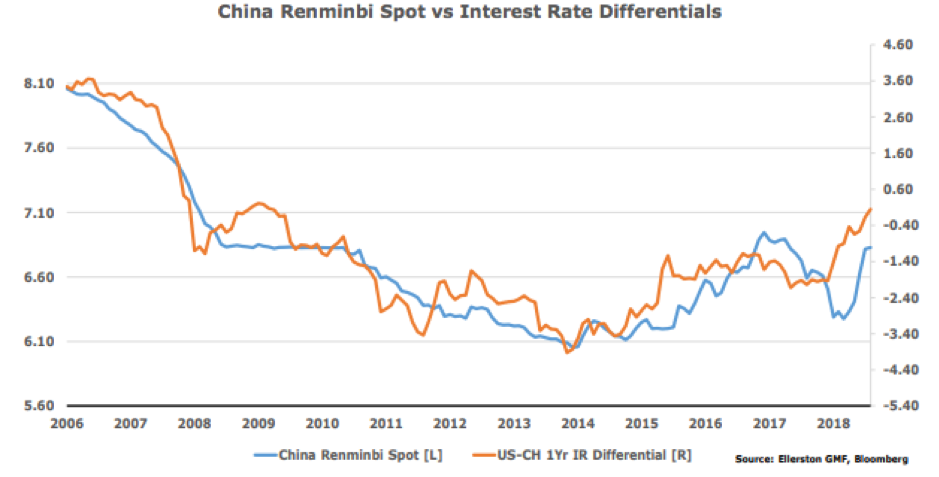

At the same time, the US has been raising interest rates, such that interest rates in the US are now higher than in China. The rate differential would suggest it is perfectly natural that CNY would weaken.

Indeed, the currency “should be” at 7.1 already. Perhaps it would be if the Chinese were not trying to SLOW the depreciation, with measures such as margin penalties for banks “shorting” the currency, as well as encouraging domestic banks to aggressively buy CNY at the close each day.

So to me, it would appear the Chinese are deliberately trying to prevent their currency falling “like a rock”. Whilst at the same time they are allowing it to “play its part”. How very modern of them!

So why is Trump convinced otherwise? Because the answer is a little more complicated/opaque in the case of China, as their currency is not freely floating. It is a managed basket approach, similar to the Monetary Authority of Singapore, but less defined.

They are in transition from a fixed exchange rate, to a freely floating exchange rate. It is this opaqueness that allows Trump to twist the facts. Well, ignore them actually. But hey, that’s what he does. The problem is he is asking China to strengthen their currency when his very own policies are driving CNH weaker.

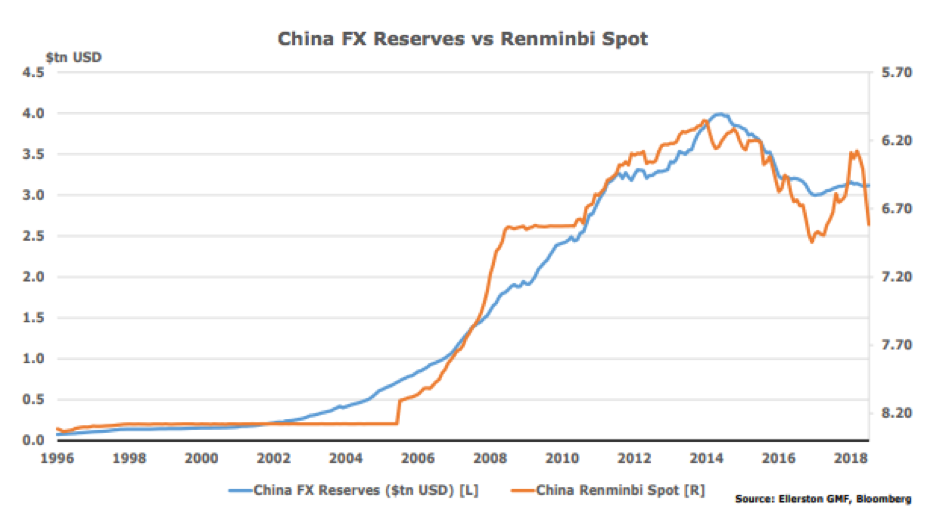

In actual fact, Chinese currency management is well progressed from 3 years ago, when they first embarked from a pegged currency to a managed currency. The lack of intervention over the last 18 months would suggest they are allowing the currency to float relatively freely. The chart below shows Chinese offshore reserves in blue. In 2000 the Chinese held 160 billion in offshore currency, predominantly USD. Typically they would invest this in US 10-year Treasuries. There for a rainy day in case there was a crisis and they needed to support their currency by selling those USD and buying CNH (a lesson from the Asian crisis in 1997). However, when they broke their peg in 2005 and allowed the currency to slowly appreciate, the trend became clear. So many investors were jumping over themselves to buy CNH and get a free appreciation in the value of the currency. Had the central bank done nothing, the currency would have appreciated very quickly and hurt economic growth. So they “leaned” against it by selling their own currency and buying USD. To the tune of nearly USD 4 trillion worth of selling of their own currency over a decade.

August 2015 was a pivotal moment. The Chinese economy was slowing, and for the first time fundamental pressure dictated it was appropriate for the currency to weaken. The Chinese authorities were slow to allow this, maintaining a peg at about 6.2 for the prior 15 months. When they let it go, the trend reversal saw Chinese citizens move their wealth overseas en masse to protect its value. The flow turned into a deluge, and the Chinese authorities had to buy almost USD 1 trillion worth of CNH, and restrict capital flows for Chinese citizens, to arrest the freefall (note the fall in reserves 2015).

At the end of 2015, they shifted to a managed basket approach, similar to Singapore. And this has been successful, in that very little intervention has been required in the currency since then (indicated by the relatively stable reserves, and also indicating Trump’s view is very last decade).

So now what? Should the Chinese stabilise their currency? One minute the world is telling them to let it float more freely, and when that doesn’t suit, Trump wants them to intervene! No they won’t intervene, except to smooth when the market gets too volatile. They are in the process of a long commitment of freeing up their currency, and they won’t take a backward step now.

So expect the currency to go where the fundamentals dictate. And where is that? Well the interest rate differential suggests a weaker CNH, around 7.1. And the interest rate differentials are likely to keep moving in the USD’s favour. Indeed our forecast in a year’s time purely on rate differentials would suggest 7.2 to 7.3. But of course there are other factors at play, in particular the tariff war and accelerated capital flows. The Chinese would very much like to avoid a repeat of late 2015, when they had to intervene heavily to stop a freefall in the currency. If sentiment shifts quickly, perhaps driven by a sudden realisation that this trade war is going to last years rather than months, it may be very difficult to control the capital flow, despite the tools available to the Chinese. Hence their smoothing in July.

So how long will the trade war last? Put it this way. No one appears close to blinking.

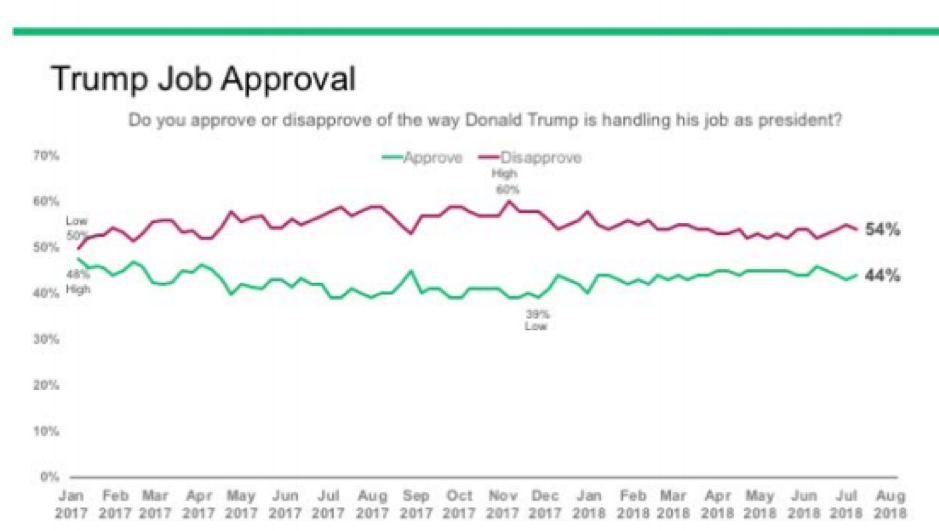

Consider the pair. (No, neither are in an industry super fund). Trump has mid-term elections in November. His polls have been the poorest in the first 18 months of any new president since WWII. But now that he has switched to trumpeting tariffs, his polls have risen.

He thinks he has found the golden nectar. Well perhaps it is for a populist politician. The point is, he is being encouraged every day to push harder in this direction. Industry is complaining to be sure, but is yet to find a sympathetic ear in the White House. He is going to go harder on tariffs into the mid-term election, not softer.

The market knows this. But it also thinks this is all brinkmanship. Once the election is done, if not just before, Trump will agree on a deal and claim victory.

So no need to panic right?

Except there are a couple of wee problems there. Firstly, President Xi has a country of his own to maintain leadership of. My consultants suggest Xi has taken personal responsibility for managing the tariff “situation”. Murmurs are mounting that he has not handled this well. Despite recently being sworn in as leader for life, he still has lurking discontents that will leap on failure. He now believes he has to show strong leadership and “win” against Trump. And a “win” does not mean backing down. The quashing of the Qualcomm deal, and the announcement (at the start of August) of a further $60 billion of goods the Chinese will impose tariffs on, both reflect a new determination of Xi to put Trump in his place.

Mmm, so it is not clear who is going to give here…

At the same time the White House is digging in. Last month Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernisation Act (FIRRMA) was expanded, giving it ability to reject foreign investments that seek to “obtain commercial secrets related to critical or foundation technologies” and investments which “reduce any technological or industrial advantage of the United States”

And the clock ticks. The US implements a 25% tariff on a further 16 billion of imports on August 23rd (bringing the total to 50 billion). China has instantly responded in kind. Public comment now closes on the proposed 25% tariff on a further 200b on September 5th. Expect the imposition about a month later. China have promised to respond with tariffs on 60 billion of US imports. Trump has promised to respond with another tariff on a further 200b if they respond! A sharp escalation in the tariff war is looking increasingly likely in September and October.

So how are we managing it? Well, brinkmanship is extremely difficult to trade. The whole idea of brinkmanship is to make the situation so unpleasant that the other guy caves in. The market is trying to look through the brinkmanship to the cave in. But in these situations it is usually the market that has to do the work of making it unpleasant. Trump is taking great pleasure in watching the Chinese stock market fall 20%. Whilst ever this is the situation, he will hold steady and assume the Chinese cave first. But if the Chinese don’t cave, it will likely be the US stock market that does the fall and causes Trump to cave.

We are holding small short positions in both the US stock market and the emerging equity ETF. However, only in options, because if either leader caves, there will be a tremendous relief rally in equities. Indeed, any talk of talking sees quick reversal in markets.

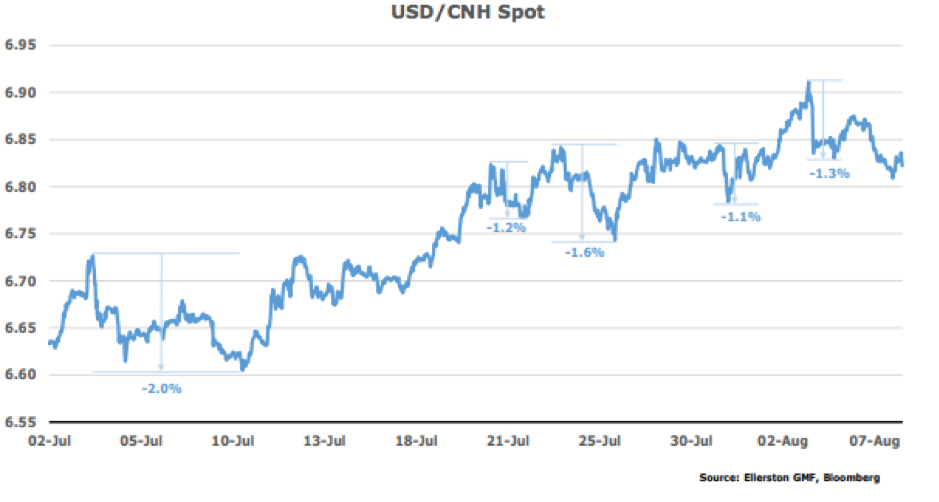

The bulk of our exposure is still in currencies, and short the Chinese currency in particular. Fundamentally, we think the currency should weaken, driven by growth, and interest rates. Tariffs could turbocharge this weakening. But in July they created a lot of uncertainty. Like equities, any sign of a resolution of the tariff deadlock will see a significant rally in the Chinese currency. Volatility increased significantly in the Chinese currency during July. CNH weakened 2.5% during July, but it corrected by 1% to 2% five times.

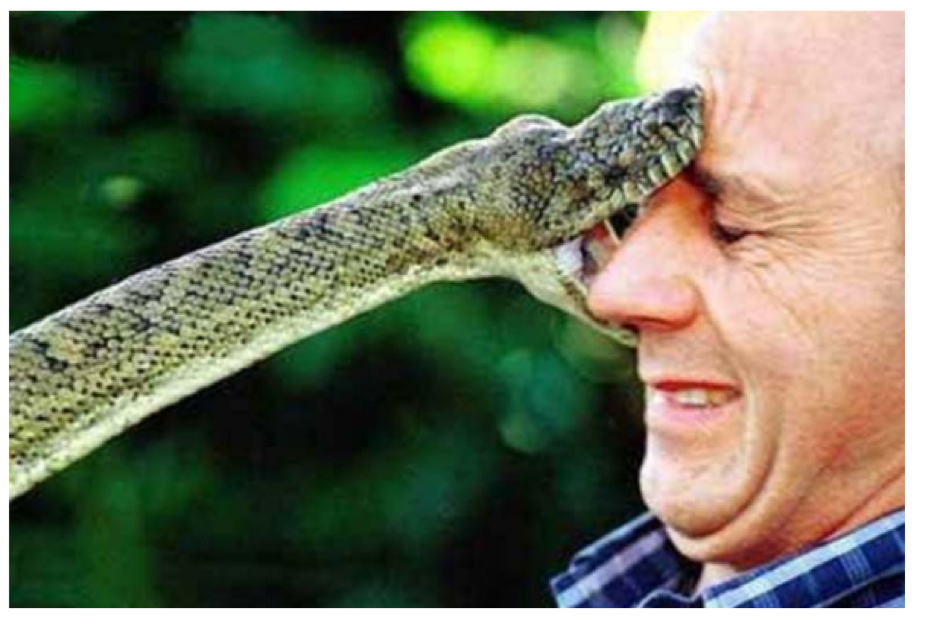

So trying to sit short the Chinese currency at the moment is not dissimilar to grabbing a snake by the tail - it is whipping all over the place!

Nonetheless, we firmly believe the move has further to go, perhaps a lot further. Capital outflows have not started yet. The tariff deadlock looks set to escalate, particularly into September. So we are maintaining this exposure.

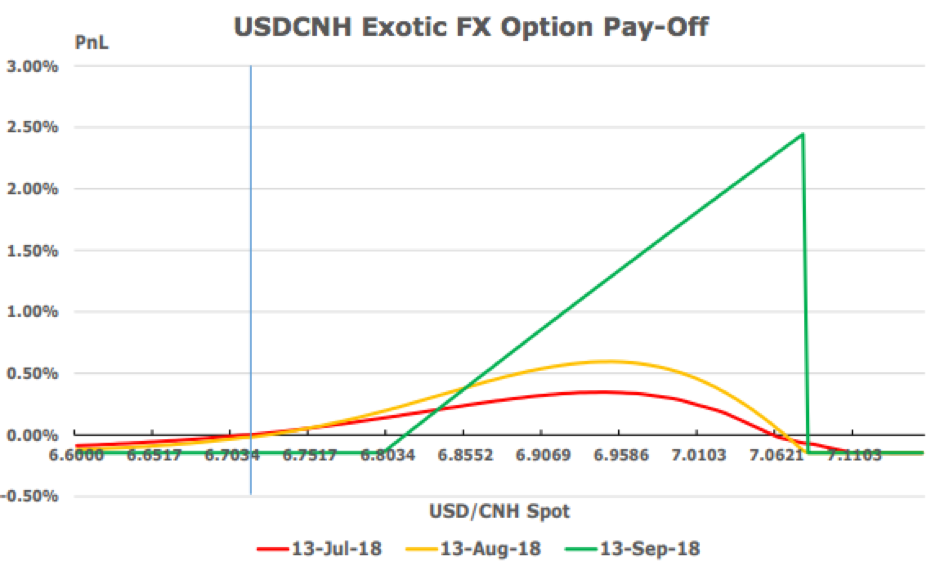

We like the opportunity the option market is presenting. The option market is very concerned about a sharp fall in the currency. So puts on CNH are trading at a premium. That means if we are willing to put a range on the currency move over the next month we will get an excellent risk-reward. For example, on the 13th July, we bought a put on CNH at 6.8. And we attached a condition to it. The condition was if CNH trade to 7.08, our option is “knocked out”, or cancelled. By attaching the condition, we get a 62% discount. Now we think recent measures from the Chinese suggest they want to slow the pace of depreciation. And that 7 will be a natural level to defend for a period. And that August will be a quieter month for tariff headlines, making 7 more defendable. So we are happy to attach the “knock-out” to the option and improve the risk-reward of a move to 7 over two months from 4:1 to 12:1.

We have a number of these structures in the portfolio, all over different dates and prices, but capturing the same idea, namely a more controlled depreciation in the Yuan over the next month before tensions increase in September and the move becomes potentially more volatile again. Perhaps we are threading the needle a little, but if right the risk-reward is very good. If wrong the loss is very controlled.

We still have a short position in US rates, but it is the smallest it has been in since inception. Once tariffs are resolved, US rates will sell-off rapidly, and we want a toe in the water in case we miss the start.

And we have modest shorts in EM equities and US stocks. Because we think it gets worse before it gets better….

About the Ellerston Global Macro Fund

The Ellerston Global Macro Fund is an absolute, unconstrained strategy investing in a number of fundamentally derived core themes, optimised via trade expression and portfolio construction across Fixed Income, Foreign Exchange, Equity & Commodities. It focuses on capital preservation while providing low to negative correlation to traditional asset classes. Find out more.

4 topics

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.

Expertise

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.