Cash is NOT the King...

Cash is king. This is a common phrase heard particularly in times of market stress, but long term investors will well know that in the long run, cash as an asset class is all but certain to underperform other asset classes such as equities and bonds. Unfortunately, what we believe lies ahead in global financial markets means that investor's cash purchasing power is likely going to deteriorate even further. In this note, we will discuss some risks (maybe some that investors haven't thought about before) that could destroy their precious cash!

Most investors have a recency bias where they think what has been, will continue. We believe we are now at a critical juncture where major fundamental changes are occurring in financial markets. The Coronavirus is just the pin that is bursting what was one of the biggest asset bubbles in history. As a result of the unprecedented slow down across global economies, central banks and policy markets are going to respond with a significant money printing in order to stimulate and help the economy through the shutdowns. Unfortunately, the consequence of this will be currency debasement. This means that the purchasing value of a dollar today is about to deteriorate significantly. What lies ahead, we believe is stagflation (inflation or prices rising on goods needed for living while unemployment remains high and growth stagnates).

This inflation is already being seen in supermarkets as people comment about prices rising on goods in high demand. The panic buying and increased demand for consumables right at the time supply chains have been decimated (due to the shutdowns) is resulting in prices rising for everyday goods. If $100 could buy you a week's worth of food, it might now only be buying 6 days worth due to price rises...and maybe even less in the future.

Right now in many countries governments and central banks are about to implement "helicopter money" literally giving cash payments to citizens in order to stimulate the economy. As everyone begins to receive payments in order to supplement their lost incomes they now no longer have due to the shutdown, they will focus on spending this money on these goods needed to survive (which are already in high demand). This further exacerbates the problem of stagflation as they continue to be unemployed yet prices for consumable goods rise.

The pressures then begin on the monetary system as endlessly money printing increases the money supply - likely resulting in further erosion of purchasing power. As more money becomes available the purchasing power of that money is further reduced depending on the level of inflation. Now perhaps counterintuitively, in periods of higher inflation, it is better to own physical assets to protect against the erosion of purchasing power caused by inflation.

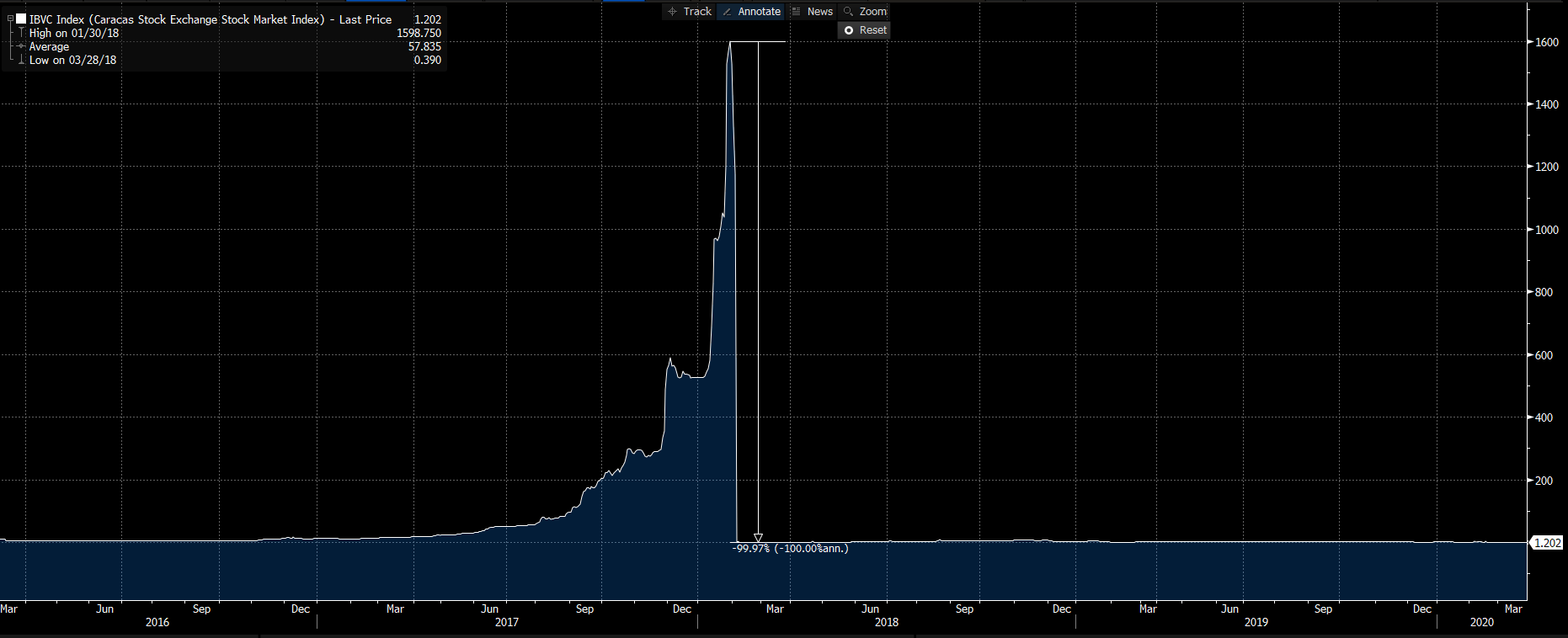

A recent example is Venezuela, where extreme hyperinflation decimated their economy. While we don't expect this to happen in the western world, it is an example to show how the stock market performed over this period...

However, when you look at the same performance in US Dollars as opposed to the local currency - the return profile is much different!

Currency debasement and stagflation are probably two of the most difficult periods for investors to navigate. With the recent stock market volatility driving investors into cash, it is potentially the next asset class to be eroded... or taken.

Another threat to investor's precious capital is the economic fall out from the coronavirus. As we discussed in our recent video presentation all crisis escalate with a banking crisis. Now if inflation returns right at the same time unemployment rises to unprecedented levels it's going to have some terrible outcomes. Not only is the purchasing power of money deteriorating, but more and more people begin defaulting on debts. Being a debtor (lender/bank) in a higher period of inflation is not good business (especially if rates are fixed). This is because the amount owed remains fixed, while the value of that money deteriorates. The only way banks combat this is by lifting interest rates (which will have serious economic ramifications) in order to try to keep pace with the devaluation and entice depositors to keep cash on deposit instead of taking it out or buying assets with it.

The second part of higher defaults mean banks become forced sellers of property into a market where not many are willing to lend credit. While banks always say they don't want to foreclose on people, they typically don't get much choice when things get nasty.

While the Australian government guarantees deposit's up to $250k (and this won't change in our view) it certainly doesn't mean figures above this amount aren't at risk. While most people know what a bail-out is. Not many know what a bail-in is.

This is where banks (should they get into financial trouble) can bail-in deposits over and above the $250k amount in order to recapitalise the bank's balance sheet. Depending on the severity of the balance sheet and level of bad debts from the economic fallout, this could mean a significant haircut to investors 'safe' cash held on deposit.

In a period where the wealth gap between classes is at extremes. It is likely to create further tensions should a banking crisis ensue. Politically, it may also seem like a better option that the wealthy help shoulder the burden, meaning that a wealth distribution event could lie ahead (in the form of a bail-in) as governments struggle with massive budget deficits and are unable to bail out the banking sector.

So

can Australian banks really fail? Well, as recent as 2008, Bankwest teetered on collapse

before being acquired by Commonwealth Bank. In Australia’s last recession in

the early 1990s (yes, Australia has had a recession before), a slew of

financial institutions collapsed (State Bank of Victoria, State Bank of South

Australia, Pyramid Building Society to name a few). Depositors were fortunate

that the Government recompensed them in these collapses, but that is not always

a given. In the 2013 Bank of Cyprus depositor bail-in, depositors with more

than €100,000 lost almost half their money and were recompensed with unwanted

equity. In the aftermath of the GFC, excessive borrowing at cheap rates led to

the Greek debt crisis when debts could no longer be repaid. This led to a run

on Greek banks, out of fear of a potential bail-in (ala 2013 Bank of Cyprus)

and currency devaluation from a potential exit out of the euro, nobody wanted

to hold cash; depositors rushed to withdraw cash out of banks and purchased

anything tangible that could hold its value.

We are not trying to fearmonger our readers, but rather pointing out that complacency along with unprecedented global events could lead to a number of unexpected outcomes. Cash in the bank is perhaps not as risk-free as you may think (right at the time most investors are running to cash). We believe that what lies ahead is going to be an extremely difficult market for the average investor. Those who don't understand counterparty risk, who can't invest globally and that can't short sell are going to struggle in the years ahead. Unfortunately, most investors don't seem to be seeing the big picture. Perhaps this time of self-isolation is important to get clarity on what the future might hold and to review your own positioning. Most investors don't seem to have much exposure to assets or managers who will do well in the period ahead... Being a global long/short manager, we would like to think we are in that category!

4 topics