CBA prints monster $4bn bond, biggest Aussie credit issue ever

CBA opened-up the Aussie bank debt issuance market for 2022 with a record $4 billion 5-year, senior bond transaction involving both a floating-rate ($3.1 billion) and an unusually chunky fixed-rate ($900 million) tranche. According to CBA, this is the largest bank or corporate bond issue ever consummated in Aussie dollars.

Apparently the next largest was Mayfield Group (?), which issued a single tranche $3.5 billion deal in 2005. The $3.1 billion floating-rate tranche is also the biggest Aussie dollar single tranche from a bank (Westpac issued a $3.05 billion single tranche deal in 2015).

We previously profiled the prospective CBA deal here. At the time, we argued that the secondary market fair value curve with no new issue concession was circa 70-71 basis points (bps) above the quarterly bank bill swap rate (BBSW). At it happened, CBA printed at 70bps above BBSW. (We were an investor in both tranches.)

While for the issuer this is the cheapest 5-year senior bond in the post-GFC and pre-COVID period, it is materially more expensive than the miniscule 41bps spread above BBSW that NAB paid in August 2021 in a 5-year senior Aussie dollar deal that was always going to set a record low watermark for the banks' cost of senior capital.

The main difference this time around is a much smaller bid from the bank balance-sheets. Since APRA announced the shuttering of the banks' Committed Liquidity Facilities, they no longer have $140 billion of cash that they can use to buy each other's bonds. Of course, there will still be some bids from smaller banks that are classified as Minimum Liquidity Holding (MLH) institutions rather than Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) banks. MLH banks can continue to hold bank paper as a substitute for government bonds. LCR banks are now only allowed to hold government bonds.

And the demand for government bonds will be significant: on our modelling (click here), banks have to buy about $408 billion of government bonds over the next few years as the CLF comes to a close, balance-sheets continue to grow (driving regulatory liquidity needs), and the RBA destroys over $188 billion of digital cash as the banks repay the Term Funding Facility and bonds mature off the RBA's balance-sheet. (This digital cash is currently included in the banks' LCRs and will evaporate over time.)

While CBA initially launched its new 5-year senior deal around our proposed target of 75bps (we suggested they print at between 75-80bps), they were able to grind the spread down to 70bps on the back of more than $5 billion of investor demand. This 70bps figure was exactly in line with our secondary fair value curve.

Dealers reported very little switching into the transaction, highlighting the substantial excess cash swirling around the financial system. There was some evidence of modest switching from bank paper, although nothing from other asset-classes like government bonds. On the break, CBA's new deal performed strongly with some dealers bidding as tight as 66.5bps over BBSW, although it seemed to settle at a bid around 68.5bps.

CBA's landmark transaction will presumably pave the way for other bank issuers, including both the majors and the regionals, although the majors have the luxury of issuing in multiple currency formats. In the first week of January, NAB issued US$4.75 of bonds in US dollars (we participated) with the 5-year issue swapping back to Aussie dollars around 70-71bps (ie, in line with the CBA trade). NAB also printed a GBP$1.5 billion covered bond. There is little doubt that there is tremendous global demand for Aussie bank paper.

When the $140 billion CLF bid was there to keep Aussie dollar bank bond spreads tight, they used to trade inside, or tight to, equivalent Aussie bank issues in US dollars and Euros. The closure of the CLF will likely see domestic spreads normalise in line with global counterparts. This has already happened with the Aussie 5-year senior curve very similar to the US dollar curve right now (historically it traded tight to the US curve).

One interesting feature of the CBA deal was the $900 million fixed-rate tranche, which is the biggest observed in years. Prior to the GFC, most bank and corporate bond issues were in fixed-rate format. But the advent of the CLF meant that bank buyers of bonds wanted floating-rate issues since banks hedge all their assets to a floating-rate return.

This drove a surge in floating-rate issuance in the post-GFC period. As long-term interest rates climb, and the CLF disappears, it would be reasonable to expect banks to tap into deeper fixed-rate demand with larger fixed-rate tranches, which they can then swap back to floating-rate format.

Demand for fixed-rate issuance is being amplified by APRA’s decision to benchmark super funds’ investment performance against a fixed-rate as opposed to floating-rate bond index, namely the AusBond Composite Bond Index. There has been substantial shifts of super fund capital from floating-rate to fixed-rate strategies to minimise tracking error to the Composite Bond Index benchmark. This will in turn fuel demand for fixed-rate rather than floating-rate bond issuance, which offshore and bank issuers can hedge to floating-rate.

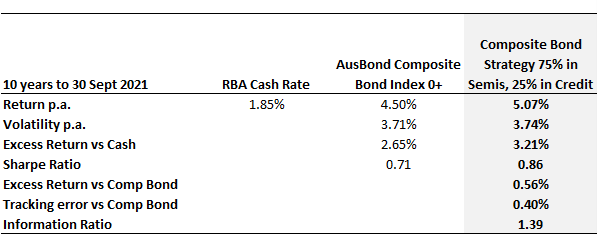

Another consequence of the rise of fixed-rate Composite Bond Index strategies will be an increase in the demand for the assets included in the index, which is mainly comprised of Commonwealth and State government bonds with only circa 7-8% allocated to credit. As we have previously written, this begs the question as to how super funds can comfortably beat the index (and accordingly pass APRA's terrifying performance tests) with relatively low tracking error. The most obvious solution is simply tilting Composite Bond strategies towards higher-yielding members of the index. Our findings were summarised below (read more here):

What we find is that a portfolio 75% weighted to State government bonds (proxied by the relevant duration-matched AusBond indices) and 25% in credit (proxied by the duration-matched AusBond Credit Indices) beats the Composite Bond Index by 0.56% annually over the last 10 years with almost identical volatility of 3.74% pa (vs the index volatility of 3.71% pa). It therefore has a superior Sharpe Ratio of 0.86 times (vs the index's Sharpe of 0.71 times). It also has a low tracking error to the index of just 0.40% pa with a high Information Ratio of 1.39 times.

One concern with just loading up on credit, however, is the illiquidity risk, which was exemplified in March 2020 when many Aussie credit funds de facto froze. The risk of liquidity shocks has been amplified with the precedent of the Commonwealth government allowing super fund members to release their savings early, as occurred in 2020, forcing many super funds to liquidate assets. (Some discovered that they were carrying too much illiquidity in the form of unlisted assets that were difficult, if not impossible, to dispose of.)

3 topics