Central banks hike - until they break things

We've consistently argued that unprecedented interest rate increases by central banks would break things, triggering a big default cycle. The US, which has experienced amongst the most aggressive monetary policy tightening programs, has suddenly felt the consequences of that elastic band snapping. So what has happened and what does it mean for asset pricing?

The Fed lifting its policy rate from ~0.25% to ~4.75% blew-up the crypto/tech markets, which relied heavily on the low-rates-for-long paradigm to support unprofitable/income-free assets/business models. The ensuing crypto/tech recession has in turn claimed the scalps of three US regional banks focussed almost exclusively on these sectors: two, Silvergate and Signature, were crypto-dependent while the third, Silicon Valley, was almost 100% tech-centric (with some crypto exposures embedded via its depositors and borrowers).

Diversification has never been important to US regional banks, which is why 25 have died every year, on average, since 2001. Hedging interest rate risk on their assets also appeared not to be a priority.

Our central case was that Silicon Valley Bank would be absorbed by a larger institution and, crucially, all its depositors made whole. The US Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC went one very large step further, likely because they wanted to avoid a rolling series of smaller US bank resolutions propagating a systemic crisis.

Fed's unlimited deposit guarantee and massive loan facility are game-changers

On Monday, the Treasury/Fed/FDIC announced a blanket, unconditional government guarantee of all US bank deposits, including those larger deposits above the US$250,000 threshold that were---prior to this announcement---"uninsured" and exposed to the possible risk of loss. All depositors at Silicon Valley Bank, including those who were uninsured, were given access to 100% of their cash on Monday. This was definitely an upside surprise for all pundits.

The Fed also announced that it will offer unlimited, 1-year funding to any US bank that wants to borrow against its eligible assets at an incredibly cheap cost of just 0.10% above the cash rate, which accordingly provides all US banks with access to extremely low-cost funding.

This is a big deal on many levels for US banks and also creates a profound precedent for all other countries. We saw similar blanket government guarantees of bank deposits rolled out during the global financial crisis. And when one country moves, others are often forced to follow.

In theory, this new US guarantee protects 100% of the value of all US bank deposits, which means that depositors face zero future risk of loss. It should in practice remove any risk of a deposit run---that is, a rush for the exits---on the basis of fears a smaller US bank might fail. This has certainly been the experience in the past when blanket deposit guarantees have been introduced. And it's safe to assume that other nations will roll-out similar protections if they are ever required.

Reduced bank default risk

Blanket government guarantees of all bank deposits, which are the banks' biggest source of funding (and hence their largest liability), very directly reduces the risk of default and insolvency on all bank liabilities, including their bonds. Since banks run leveraged mismatches between their assets (long-term loans) and their liabilities (short-term deposits and bonds), they are always at risk of a shortfall of funding if deposits walk out the door.

This is why central banks were set-up in the first place: to provide loans (liquidity) to banks that were subject to temporary funding shocks as a result of a deposit run. It is also why almost all global governments have extended this public back-stop of banks to explicit government-guarantees of deposits (and in the 2008 crisis, government guarantees of their bonds) to prevent any risk of future deposit runs and consequent bank failures.

Faster policy reaction function

When you think about it, it is understandable why taxpayers are keen to guarantee the stability of the banking system: the economy relies crucially on the ability of our savings to be converted into loans via trusted intermediaries (ie, banks). We are much more likely to park cash in a bank deposit if it is guaranteed to be risk-free. If we don't save and make cash available via deposits, there will be no loans for businesses and households to borrow. And the economy is screwed.

Having said that, I don't know anybody who expected such bold and unconditional action to back the US banking system by the relevant government agencies. This initiative was clearly designed to ensure that the failure of a few smaller banks, which, as I explained on the weekend is a surprisingly common occurrence, would not metastasize into a more systematic crisis.

In past crises, policymakers have had a tendency to respond slowly, and in a graduated fashion, which has often exacerbated the fear/uncertainty, only to belatedly roll-out their bazookas. In this event, US decision-makers brought out the bazookas upfront, which was definitely the right move.

Bonds rally, equities stable, credit spreads wider

The market reaction has been fascinating. US equity futures initially jumped circa 1.7%, but at the time of writing are roughly unchanged to slightly up. US regional bank equities continue to cop a beating on the basis of concerns that, amongst other thing: (1) their funding costs will increase, reducing net interest margins and profits; (2) there will still be a structural shift of deposits out of smaller banks into larger institutions; (3) they will be subject to much tougher regulations, and forced to hold more capital and higher quantities of liquid assets, crimping returns on equity; and (4) recognition that the Fed's unprecedented interest rate increases are finally biting, weighing on expectations for future earnings.

At the same time, fixed-rate bonds have soared in value as yields---and hence interest rate expectations---have slumped. US 10-year government bond yields have dropped from 4.05% to 3.53% (Aussie 10-year government bond yields have plunged from 3.90% to 3.35%). So-called interest rate duration has, as a result, performed exceptionally well.

Whereas the Fed was expected to lift its policy rate from its current level of 4.50% to 4.75% to as high as ~5.50%, bond markets have pared back pricing for the peak Fed Funds Rate to only ~4.75%, which translates into less than one additional hike. And they project that the Fed will cut rates 80 basis points by January next year. Market pricing for the RBA's peak terminal cash rate has similarly contracted from ~4.25% to current estimates around 3.85%, which suggest that Martin Place has one more hike to go.

While yields have dropped, credit spreads have widened sharply by some 30-40 basis points for the large US banks' 10-year senior bonds, and much more (eg, up to 200 basis points plus) for the smaller regional banks.

Even though this event is powerful vindication of APRA's ultra-conservative approach to setting bank capitalisation and liquidity levels, Aussie bank bond spreads have moved in sympathy as markets have indiscriminately shunted all spreads wider. This means that all-in yields on these bonds have not moved a great deal (ie, they remain historically high).

And outside of the directly impacted US regional banks, the move has been fairly orderly compared to past shocks (eg, March 2020): overnight in the US dollar market, traders net sold bonds to clients worth about US$265 million on what was normal trading volumes (US$3.5bn of sells vs US$3.75bn of buys).

Aussie banks' liquidity and capital standards vindicated

I have not previously focused on what this means for the Aussie banks and their regulator, APRA. A quick summary will suffice.

There is definitely a global flight to quality right now, which Aussie banks, as among the safest institutions on the planet with prized AA- ratings, are benefiting from. They are generally outperforming peers in terms of the change in their cost of capital.

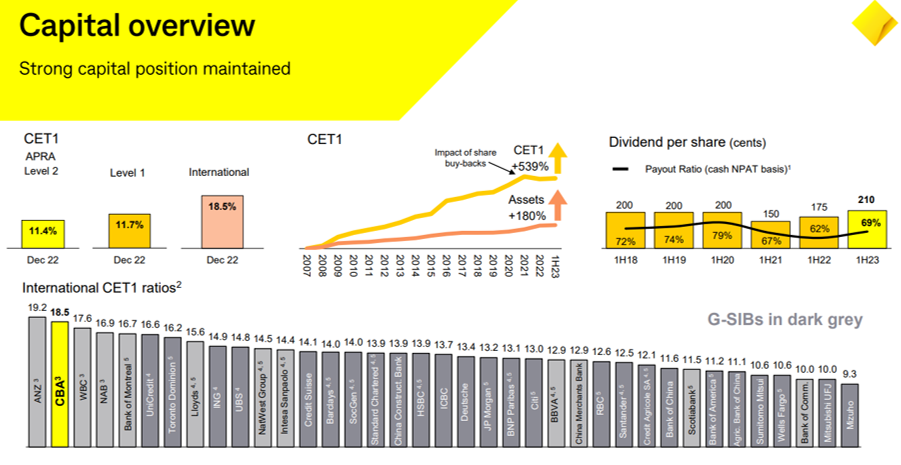

The big Aussie banks have among the highest risk-weighted capital ratios, and hence lowest leverage, of any peers overseas because of APRA's decision in 2014 to force them to adopt "unquestionably strong" capital ratios. This required the four major banks to boost their equity capital buffers by about $150 billion in the ensuing years. As the chart below shows, the four majors have the best capital ratios of any peers globally.

APRA has taken arguably the toughest line globally on bank liquidity, only allowing the big Aussie banks to hold government bonds as their last "line of defence" liquidity buffer. This contrasts with US and European banks, which can and do hold bank bonds, residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS), and commercial property mortgage backed securities (CMBS). (There had been some bank lobbying to allow RMBS and covered bank bonds as a Level 2 liquid asset in recent times, which we advised APRA against in November last year.)

Aussie banks used to be able to hold RMBS and bank bonds as a liquid asset until 2021, but APRA shut-down this loophole when it closed the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF), as we had argued they should do. At one point, the CLF was as big as $240 billion.

APRA has also taken a conservative approach to the optimal Liquidity Coverage Ratios (LCRs) Aussie banks have to maintain. These LCRs measure the ratio of a bank's liquid assets---in Australia's case, these are just government bonds---relative to the Net Cash Outflows (NCOs) they would suffer in a 30 day bank run.

The minimum Basel 3 standard for LCRs is 100%. But Aussie banks have consistently run, on average, LCRs that are around 130-135%. Once again, there were some bankers arguing last year that they should be able to operate with lower LCRs of 120-125%, which is a move we pushed back against. APRA clearly had no interest in the idea.

In contrast to some US regional banks, Aussie banks are also very vigilant in hedging all the interest rate risk on their assets back to a short-term, floating-rate that broadly matches the interest rate risk of their deposit liabilities, which are similarly short-dated. If a liquid government bond suffers a decline in its mark-to-market value, Aussie banks have to adjust their regulatory capital ratios to reflect this impact even when the bond is held in their accruals (ie, not marked-to-market) book. Silicon Valley Bank did not do this.

Australian bank depositors do benefit from a government guarantee up to $250k, and during the 2008 crisis this was available up to $1 million (beyond which you could guarantee all deposits irrespective of size for a fee). Aussie senior bank bonds were also government guaranteed during the GFC. And our big banks pay a special fee to the Commonwealth government of 0.06% per annum on the value of their wholesale deposits and bonds as a de facto insurance premium in recognition of the fact that they are treated by investors as being implicitly government-guaranteed.

Key take-aways

I think the US move to explicitly guarantee all bank deposits irrespective of size unambiguously and fairly permanently reduces US bank credit risk, and, in particular, the possibility of defaults on their bonds. It will all but eliminate future bank runs, which in turn eliminates most bank insolvency risks. While it is very positive for bank deposits and bank bonds, it is probably negative for bank equities because US banks will face much tougher regulatory requirements going forward, and by held to far higher liquidity, stress-testing, and capital standards in many instances. At the margin, this will reduce US bank returns on equity. Across the capital structure, this is therefore positive for bank creditors and negative for bank shareholders. But it will take investors time to figure all of this out, so expect some volatility---and attractive entry points---in the interim.

3 topics