Will China tighten further?

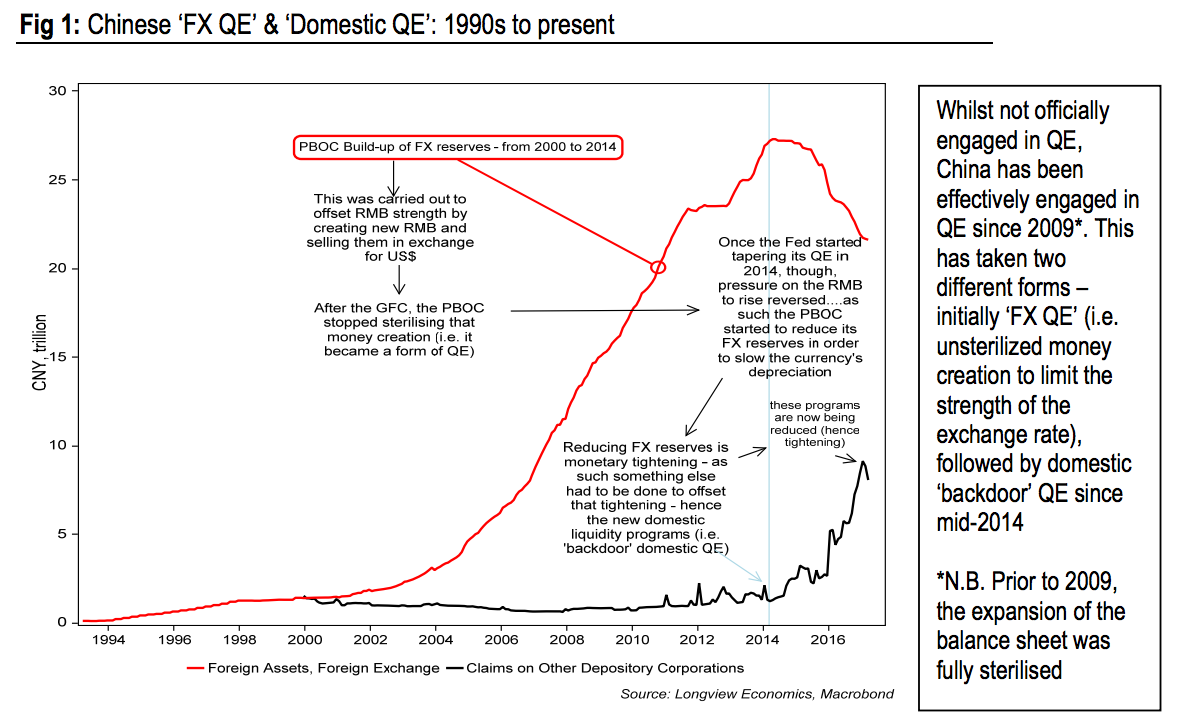

China’s central bank balance sheet is the biggest central bank balance sheet in the global economy, and has been for several years. That reflects China’s two bouts of QE over the past 10 years. Initially China carried out a type of QE we label ‘FX QE’, i.e. from 2009 through to 2014, as its FX interventions went unsterilized post GFC.

In 2014 as the Fed began its tapering then the PBOC switched its ‘FX QE’ to ‘domestic QE’. Whilst superficially, those two bouts of Chinese QE were not carried out in the manner of US & UK QE in recent years, they are effectively the same: that is the PBOC increased net liquidity in the domestic banking system, at the same time as expanding its own balance sheet (i.e. by creating new RMB).

In recent weeks, the PBoC has started shrinking its balance sheet. That is, it has been tightening monetary policy. That has been achieved by increasing the cost of the liquidity (i.e. MLF interest rate) and reducing the amount available. The outstanding liquidity provision to banks, having risen by 7.5x in the past two years, peaked in January (at RMB 9.1 trillion) and has since fallen for the past two months (fig 1c).

Added to that the interest rate of the largest of the domestic QE programs (i.e. the MLF liquidity – direct liquidity for commercial banks), has been raised twice this year (i.e. the ‘price’ of the liquidity has been increased) – fig 1a. Repo rates have also increased this year. Reflecting that tighter liquidity environment, interbank lending rates have continued to squeeze higher in recent weeks (with 12 month SHIBOR making a new multi-year high overnight, see fig 3 in attached)

The key question at this stage, therefore, is: How tight is too tight? And indeed is any further tightening likely to be implemented given the forthcoming 19th National Congress of the Communist Party in the autumn. The consensus in financial markets is that the Chinese authorities will be focussed on ensuring that growth remains on track ahead of that key event.

Policy errors are, though, possible (e.g. as witnessed during the bursting of the stock market bubble). Equally the recent appointment of Guo Shuqing to Head of the China Banking Regulatory Commission (in February) signalled a desire (from the Chinese leadership/Xi) to address the financial instability risks. That intention was backed up by an editorial in the Xinhua (i.e. government mouthpiece) earlier this month:

“Commentary: China means business with its tough financial regulation”, 4th May 2017: Source: Xinhua (VIEW LINK)

Judging ‘how tight is too tight?’ is the key to the outlook for the Chinese and global economy and the shape of relative global sector performance over coming months (with global materials stocks already underperforming, but the global industrials sector currently at record highs).

Whilst difficult to judge with a high degree of confidence, it’s noteworthy that interbank lending rates have already backed up by 1.5 percentage points since early 2017 (in the case of 3 month SHIBOR – fig 3). In the last house price upswing (i.e. from 2012 into 2103), that magnitude of tightening (coupled with some macro prudential measures) resulted in a phase of slowing Chinese property transactions, weak house price growth, softening of construction activity and, most importantly, a slowdown in credit growth (for detail see April 2017 Commodity Fundamentals Report “China, Housing Cycles, Monetary Tightening & Copper”).

On balance, therefore, China has probably already ‘tightened enough’.

Livewire readers can access the report here: (VIEW LINK)

5 topics