Compounding & taxes: a checklist for taxpaying investors

Most investors are aware of the power of compounding in terms of delivering long-term wealth creation. Buffett and Munger have repeatedly spoken of this 4th dimension of wealth creation, the ability to earn returns on previously earned returns.

However, one often overlooked issue with compounding is the impact of taxes.

Unfortunately, tax-paying investors never come close to receiving the published returns generated by the ASX200. As dividends and franking have accounted for nearly all of the market’s return the past 16 years, these returns may have been almost halved for investors in the top marginal tax bracket.

The same is true for any income-centric source of returns. When it comes to long-term wealth creation, income-based return profiles generally offer a meaningful disadvantage with respect to more capital-growth driven returns.

In this wire we’ll analyse the recent after-tax returns of the S&P/ASX300 Index. Furthermore, we believe the issue of tax drag on compounding is only increasing, as portfolios broadly shift to more income-centric sources of return such as term deposits and bonds. Herein lies the opportunity for advisors to add meaningful value to their clients’ portfolios…considering genuine after-tax returns.

Small differences add up

As Buffett says. “It is obvious that a variation of merely a few percentage points has an enormous effect on the success of a compounding (investment) program. It is also obvious that this effect mushrooms as the period lengthens.” [1994 letters].

Taxes can cause such variations to arise. There are two reasons for this:

- Income taxes are filed and paid annually, meaning that the amount of capital that is able to be reinvested each and every year is reduced. The higher the annual tax burden, the less available to reinvest for the following year.

- The tax rates on long-term capital gains are more favourable, in Australia attracting a 50% discount versus the investor’s marginal tax rate. All gains are still taxed, however the rate applied can be considerably lower.

After-tax returns and franking

Most of the focus on after-tax returns for Australian equities is based on the simple inclusion of franking credits. We believe this is a little misguided.

All eligible Australian investors benefit from franking (assuming the franking eligibility rules are met), whether they are tax paying or in a zero-tax environment. The value of the franking is the same, it’s just that the mechanism for returning this value is different.

- For very low tax payers this value can often be delivered via a cash refund from the Government.

- For higher-tax paying investors the value is realised via a credit on tax that would be otherwise owed.

Either way, the nominal value is the same and is taxed accordingly. We believe franking credits should be considered alongside and on equal footing with all other sources of return in an investor’s portfolio, namely income or capital growth. This explains why we include franking in the benchmark for our Australian fund.

There’s nothing wrong with assuming a zero-tax environment, but it does largely ignore the real-world outcomes for investors in Super (Accumulation) or in higher marginal tax rates. Not everyone lives in the Bahamas!

Checklist for after tax returns

For all of those investors sitting outside a zero-tax environment, we believe the following considerations should be front of mind when considering genuine after-tax outcomes:

- Turnover – strategies with reduced turnover can reduce the likelihood of distributing realised capital gains, whether short-term or long-term in nature. Distributed capital gains are taxed in the year realised and thus works against efficient compounding.

- Long term capital gains – If capital gains are to be distributed, then favouring long-term (greater than 12 month) gains can attract the 50% discount, effectively halving the tax obligation on disposal versus the marginal tax rate.

- Unit price growth – perhaps the most efficient tax outcome for equity investors is to see most growth occur via the unit price, which can be 100% efficient and increases the likelihood of the taxable gain (on disposal) attracting the 50% discount on long-term capital gains.

- Natural tax offsets, such as expenses – Fund expenses such as financing on leverage or tail protection costs, may all be incurred in the course of managing the investment strategy, but can help offset assessable income.

The goal for efficient after-tax returns, in a tax paying environment, should be to maximise the proportion of returns from capital growth. This conclusion is consistent with a recent SPIVA report which analyses after-tax returns for US investors and compares active management with Index exposures.

The taxman will still get his due, however by reducing assessable income in a given year, the investment has the ability to compound more efficiently. Furthermore, the deferral of gains means the investment is more likely to attract favourable tax rates reserved for long-term capital gains.

The S&P/ASX200 Index is relatively tax inefficient for a tax paying investor

Relative to other equity markets around the world, the average gross yield of ~6% on Australian equities presents as relatively tax inefficient for tax paying investors. Certainly, relative to the S&P500 Index or Nasdaq-100 Index, where the return from dividends is generally less than 2% and most return is often delivered via capital growth (and efficient compounding).

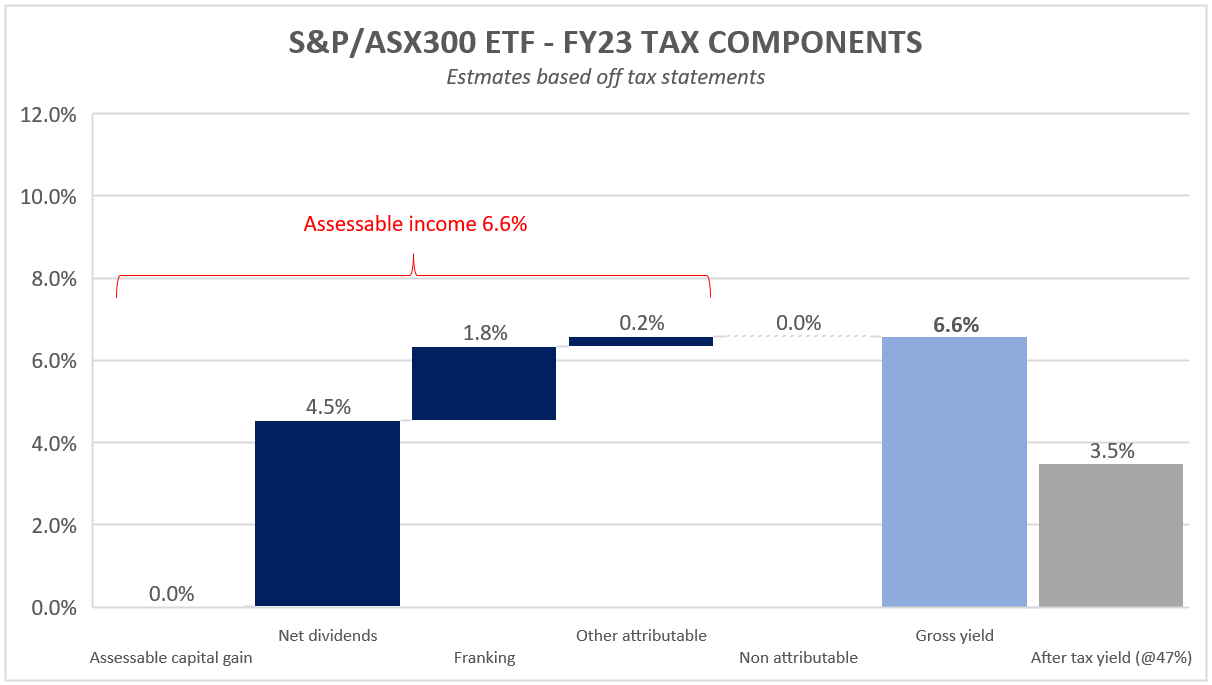

We have reviewed the tax components for financial FY23 for a leading ETF that represents direct exposure to the S&P/ASX300 Index.

Source: Wheelhouse. Estimates are based upon available tax components. The example provided is hypothetical and may differ to actual taxation impact for different investors.

This ETF is a passive exposure, so it makes sense there are minimal realised capital gains.

The tax components reflect the dividend yield of the market, with a cash yield of around 4.5% and franking benefit of 1.8% broadly consistent with longer term averages (the franking component a touch higher than average). As a result, we estimate the assessable income for the year to be 6.6%, which could create a considerable tax burden for an investor in the top marginal rate.

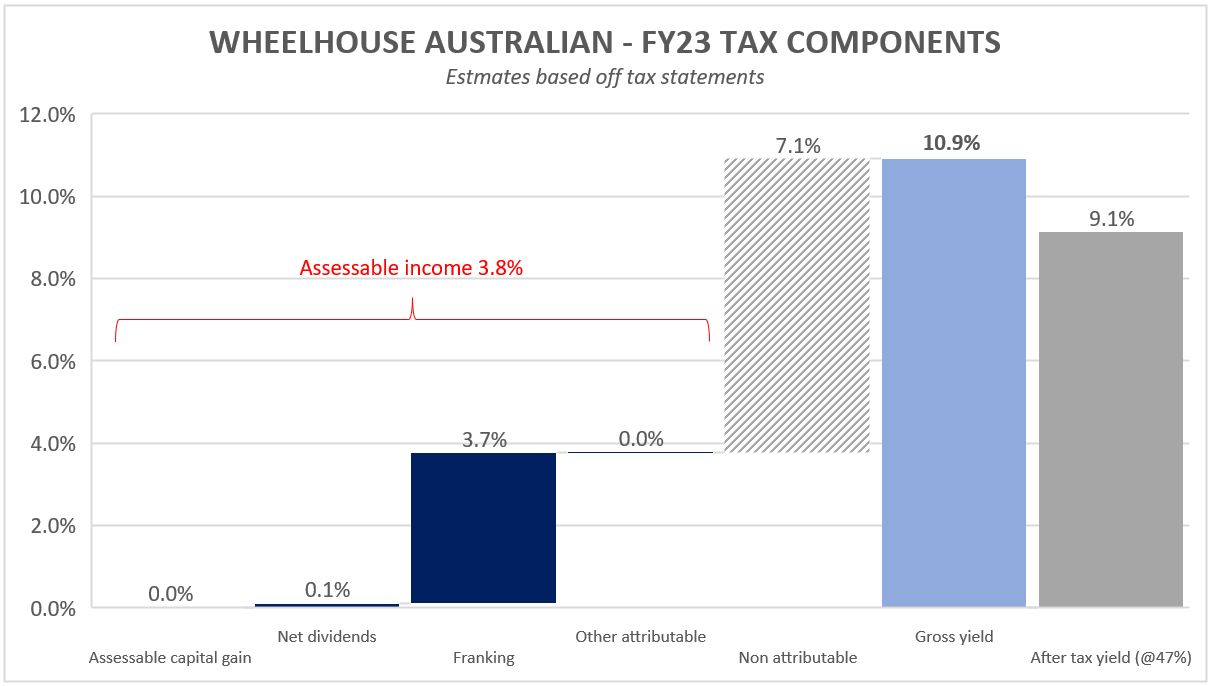

To contrast, we have run the same analysis on the Wheelhouse Australian Enhanced Income Fund for financial 2023. The results are unusual for an ‘Income’ fund, or for any dividend heavy exposure.

Firstly, there are no realised capital gains, in part because the strategy has very low turnover, typically less than 5% annually.

Furthermore, the underlying equity portfolio is internally geared, which is why the fund has the potential to receive dividends and franking on up to 2x the S&P/ASX200 Index*. This explains why the franking component is also elevated.

Finally, as a by-product of the investment strategy, there are a number of expenses such as financing costs and tail protection costs, which can work to offset the assessable dividend income. As a result, the assessable income for FY23 was meaningfully lower than a passive exposure to the S&P/ASX300 Index, as represented via the ETF above.

There was a 7% cash distribution from the Fund which impacted the unit price, however this was not attributable income and could be reinvested with zero tax drag.

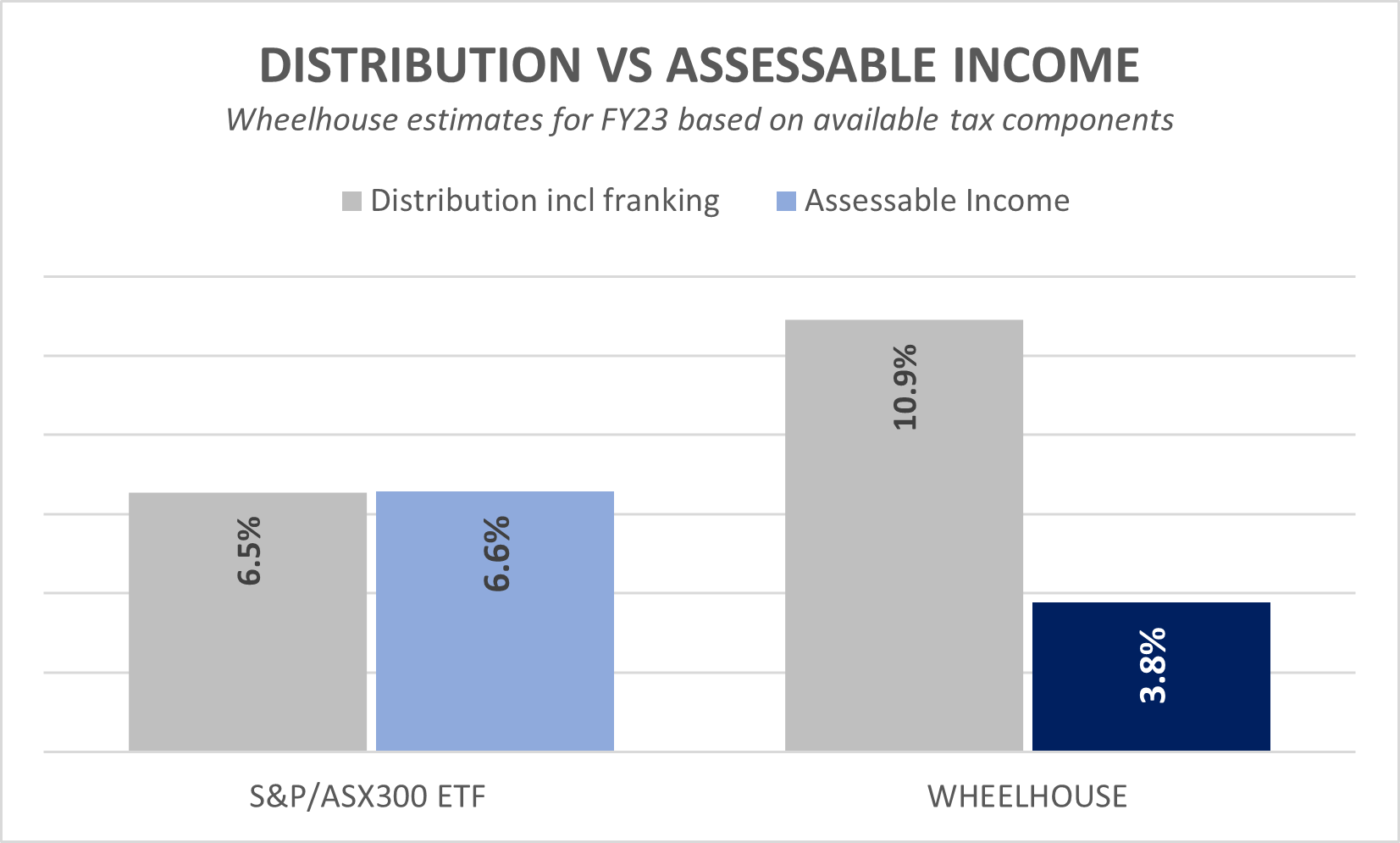

Distributions do not always equal taxable income

As a result of the different tax components, the assessable income can be very different to the reported distribution. For example, in FY23, the differences between distribution and assessable income are illustrated below. The assessable income of our Australian Fund is estimated to be roughly half that of the market ETF.

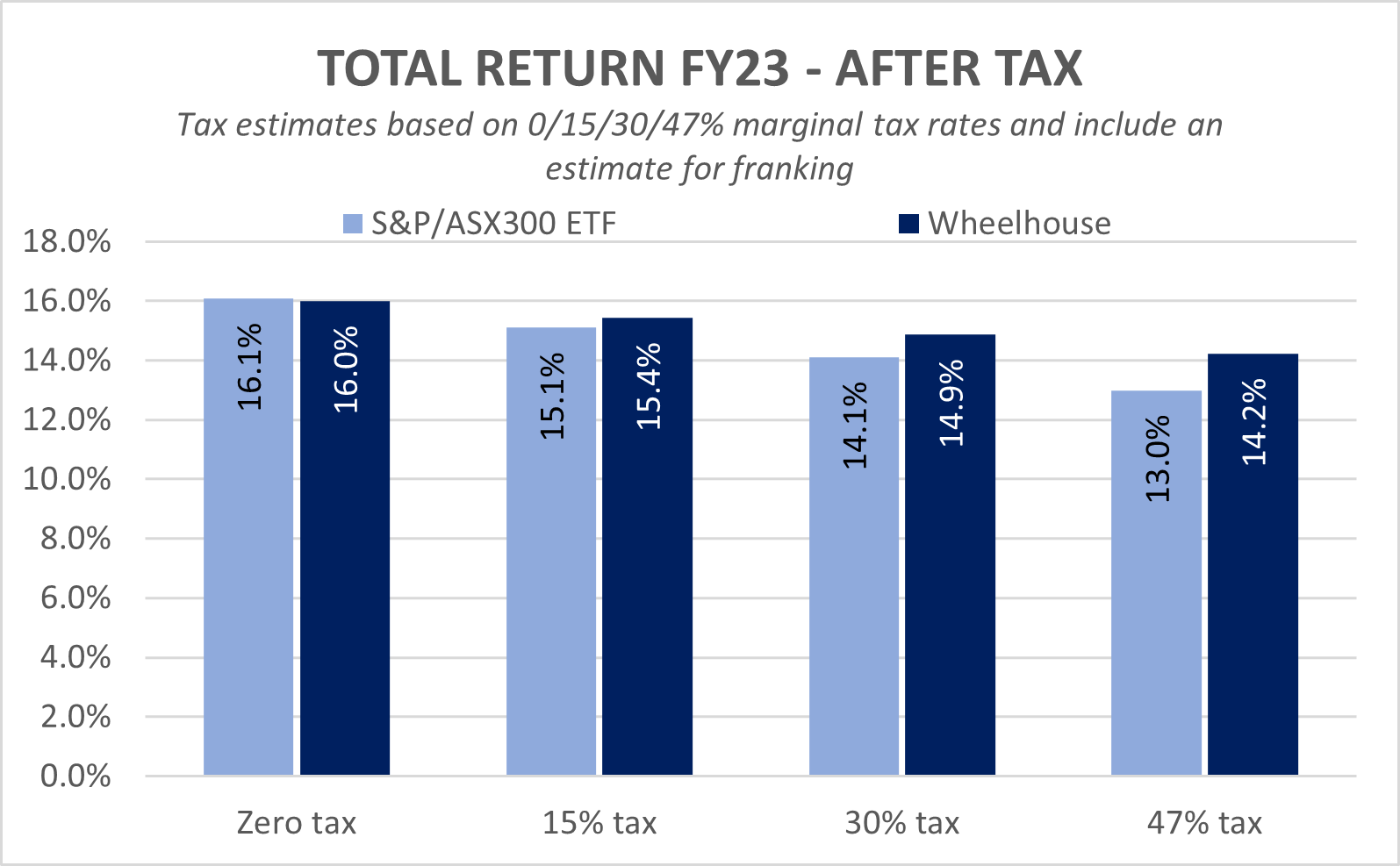

This is despite the Wheelhouse Fund delivering similar reported returns to the ASX300 ETF, after franking is considered. However, as soon as marginal tax rates are applied, the performance difference begins to appear. The more that is kept each year means the more that can be reinvested and begin working for the following year. This is the key element of compounding, earning potential future returns on previous returns earned.

Source: Wheelhouse. Estimates are based upon available tax components. The example provided is hypothetical and may differ to actual taxation impact for different investors.

We have also reviewed the tax components for a number of active Australian equity managers, please contact us for further details. No surprises, more income-centric returns and more active strategies (with higher turnover) were less tax efficient for tax-paying investors.

Conclusion

Compounding remains the 8th wonder of the world, at least according to Einstein. Most long-term investors recognise and understand these benefits. However, just as Munger recognised,” The first rule of compounding: Never interrupt it unnecessarily”.

Being tax-aware can materially impact the efficiency of compounding and long-term wealth creation. This is even more the case for income-centric return profiles, such as Australian equities, term deposits, bonds and private credit.

There are clearly roles for these investments in a portfolio, but consideration must also be given to their relatively higher tax burden, and thus to their relatively inferior ability to compound wealth.

Tax planning remains a key area of value-add for financial advisors, and one that can be far more predictable versus forecasting asset class returns. Even improving an asset’s ability to compound by 50-100bps/ year can lead to a massive difference in wealth creation, as Buffett says a ‘mushrooming’ of value as the period lengthens.

*Disclosure: Investors should be aware that different investment schemes carry varying degrees of risk that should be considered prior to making an investment decision.

3 topics