Cooking up a housing bull BBQ

In the AFR I write that back in early 2020, this column dusted off its double-barrel “shottie” and went hunting housing bears, which were confidently roaming everywhere. While it was seemingly mission impossible—one lonely, albeit bold, bull surrounded by “hangry” grizzlies salivating over 10-30 per cent house price falls (if not more)—it ultimately proved to be a one-sided massacre. A bear blood-bath, if you will.

This column argued prices would only fall 0-5 per cent (they shed 2 per cent) between March and September 2020, following which they would spike as much as 20 per cent, which we subsequently revised to 25-30 per cent. In the final analysis, Aussie home owners banked capital gains worth 29 per cent.

Fast forward to October 2021, and this weary bear hunter declared that the cross-hairs were going to be turned on the hordes of rabid housing bulls, who were now triumphantly roaming the real estate savannah, bloated on record prices. It was time to chow down on a juicy “bull BBQ”.

Specifically, we predicted that national dwelling values would climb at least another 5 per cent (they are up 5.4 per cent) before suffering a record 15-25 per cent slump after the first 100 basis points of RBA rate increases. It was expected that the RBA would kick-off this process in mid 2022 at the earliest.

The universally bearish retail and investment banks, which had been forced by the price action in 2020 and 2021 to embrace our bullish views, had seemingly learnt their lesson this time around. Within a few months of our October proclamation, most banks had swung 180 degrees, suddenly projecting sharp price falls (although none as savage as our 15-25 per cent draw-down).

That all changed on Friday when Australia’s biggest bank, CBA, folded, finally calling for a national peak-to-trough decline of 15 per cent as a consequence of the RBA’s aggressive tightening cycle.

Given the banks’ rapid error correction, tasty bulls have, in fact, been relatively hard to sight since late last year. To be sure, there are still a few solitary beasts peddling the preposterous idea that house prices will not decline as borrowers’ purchasing power plummets care of a huge rise in mortgage rates.

What the RBA giveth, it now taketh away. Slashing its cash rate from 1.5 per cent to 0.1 per cent between June 2019 and November 2020 boosted Aussie house prices by 37 percentage points. A prudent person should now assume that much of this wealth creation is paid-back.

Despite Martin Place not being able to accurately forecast its next foot-step, it somehow has conviction that the cash rate should climb to what it judges to be a “neutral” level around 2.5 per cent. The truth is the RBA has zero clue where neutral actually lies, and would be well served by some humility on this front.

For crazy-brave housing bulls and home owners across the country, the scary thing is that our forecast for a 15-25 per cent decline in national prices was predicated on the RBA lifting its cash rate by at least 100 basis points. And yet the current plan, according to Governor Phil Lowe, is to leap to 250 basis points. We have not revealed what we think will happen to house prices if the discounted variable mortgage rate does indeed lift from circa 2.25 per cent in April 2022 to 4.75 per cent next year.

Traders like to comfort themselves with the experience of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, where Governor Adrian Orr has led the world in jacking-up his cash rate from 0.25 per cent in September 2021 to 2.0 per cent today.

The market myth goes that notwithstanding that New Zealand house prices have crashed, the RBNZ just keeps on lifting. This is complete BS. The RBNZ’s official house price index is a series produced by CoreLogic, which also publishes Australia’s leading home value benchmarks.

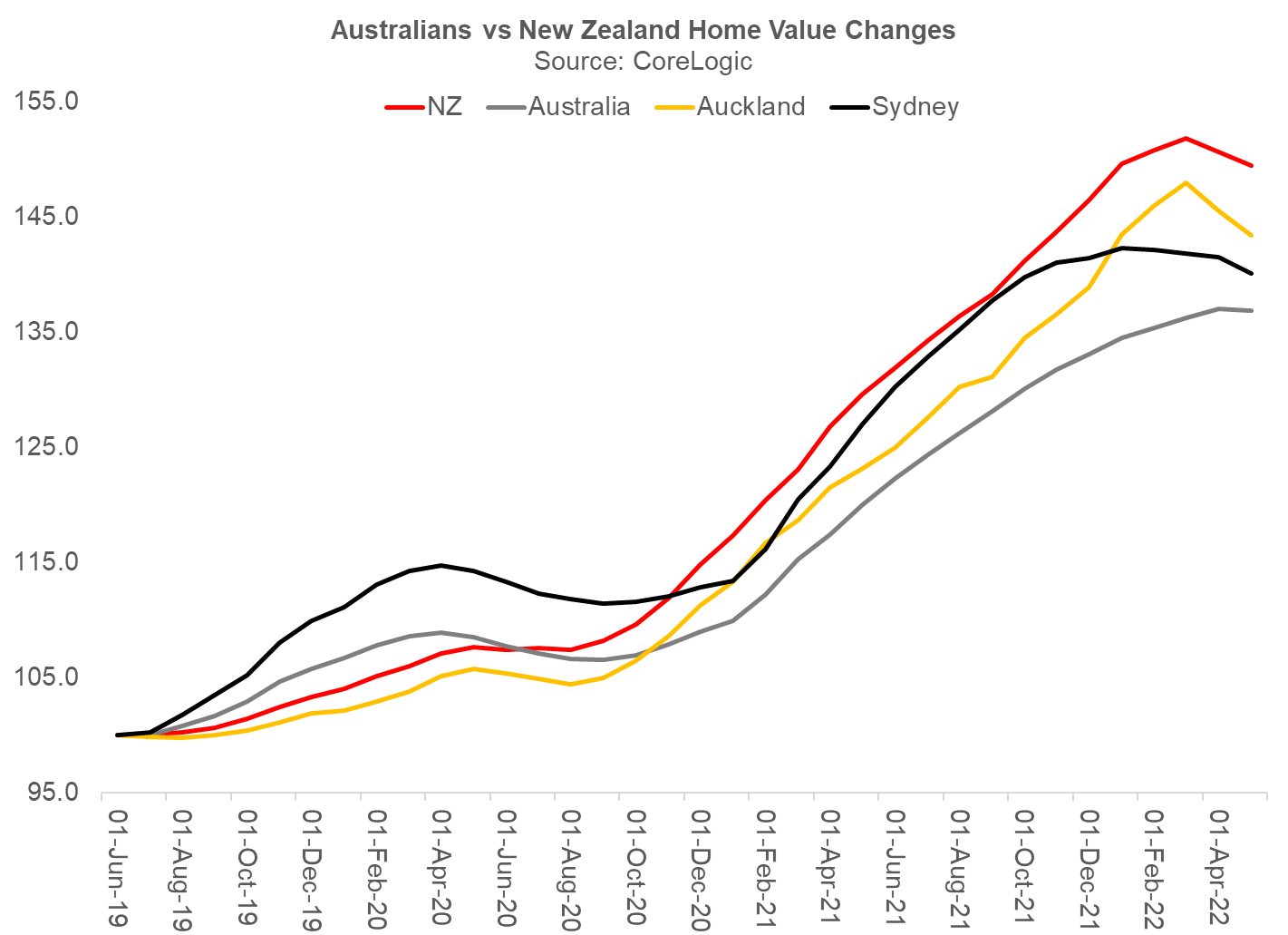

It turns out that NZ dwelling values have hardly moved in the face of 175 basis points of rate increases. From their peak in March 2022, NZ prices have only declined 1.6 per cent. (Other unofficial indices put the correction at a slightly larger 3 per cent.) NZ’s largest city, Auckland, has worn price falls of only 3.1 per cent thus far.

Indeed, it is clear the Sydney housing market started rolling over in early 2022, ahead of its NZ counterparts. It is also obvious that Aussie house prices are much more sensitive to rate changes.

Whereas the RBNZ began lifting rates back in October 2021, the RBA only kicked-off in May this year. And yet Sydney prices are already down 2 per cent with Melbourne (off 1 per cent) following closely behind.

A key difference is that whereas 88 per cent of NZ home loans are fixed-rates, and therefore insensitive to RBNZ increases, most Aussie home loans are variable-rate. The majority of Aussie borrowers were accordingly whacked by a 50 basis point increase in their monthly interest bill when the RBA delivered a double-whammy this month.

The mythology of the RBNZ bravely raising rates in the face of huge house price falls is just a fairy-tale.

For the foreseeable future, however, the RBA is going to be racing towards its terminal cash rate, which bond markets are currently pricing at around 4 per cent. Imagine that, discounted variable mortgage rates rising to 6.5 per cent!

This is nonetheless throwing up some pretty interesting and unusual opportunities. Consider NAB’s latest hybrid issue (NABPI), which attracted more than $3.1 billion in investor demand (NAB issued $2 billion). NAB is paying a 3.15 per cent income margin above the quarterly bank bill swap rate, which is 1.5 per cent. That means investors will be picking up a 4.65 per cent annual running yield on the new NABPI hybrid.

Yet if we consider the expected yield over the life of this 7.5 year hybrid, which accounts for the market’s projection for the RBA cash rate climbing to 4 per cent, the yield to maturity (or yield to its expected repayment date) is 6.95 per cent.

That means that NABPI’s yield to maturity of circa 7 per cent is almost identical to the franked dividend yield shareholders earn on NAB’s equity, which is also 7 per cent. And it is above the 6 per cent franked yield you get on Aussie equities, which is one reason why we also bought it.

Major bank hybrids have historically had about one-quarter of the volatility of major bank stocks. And they have also outperformed during shocks: when the pandemic first hit in March 2020, NAB’s shares fell 34 per cent. In contrast, the major bank hybrid index only lost 6.3 per cent in that month.

Another example of unusually attractive income returns was Macquarie Bank's recently issued 5-year Tier 2 bond, which paid a yield of 6.1 per cent. We bought it because we don't believe the RBA will get close to a 4 per cent cash rate.

Whether that comes to pass will depend a lot on what happens to Aussie house prices, which are one of the purest representations of the RBA's monetary policy transmission mechanism. It is very hard to imagine Australia will have any inflation problem when house prices have fallen by more than 15-25 per cent...

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

3 topics