Core inflation is higher than we think: will the RBA look through it?

Government subsidies have limited the effect of sharply higher construction costs on inflation, but new home prices will soon bounce back as the subsidies fade, boosting headline inflation by about 0.3 percentage points.

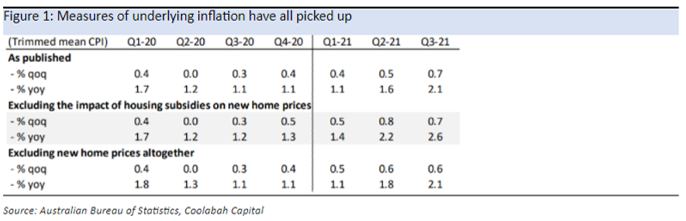

Underlying inflation has returned to the 2-3% target band much sooner than expected and could have reached the mid 2s had it not been for these subsidies.

A sharp rebound in new home prices will be excluded from the calculation of underlying inflation, but stronger momentum in prices outside of housing suggests that underlying inflation could average 2.25-2.5% in the first half of 2022, raising the risk that there is less spare capacity in the labour market than currently thought.

One key to the inflation outlook will be how quickly governments can resume skilled migration to deal with labour shortages created by closed borders as the jobless rate converges with the NAIRU. Government subsidies have kept a lid on the impact of sharply higher construction costs on the CPI.

During the pandemic, government grants for building homes have limited the pass-through of sharply higher new home prices to the CPI.

The cost of building a house has soared, with record prices for both timber and steel as local and international demand has greatly outpaced supply.

New home prices are up 9% from pre-COVID levels as a result, with government subsidies capping the increase at 5% by the time they are included in the CPI (the subsidies are treated as an effective reduction in the price of a new home).

Given new home prices are the largest single component of the CPI with a weight of almost 9%, this means that headline inflation of 3.0% over the past year would have been about 0.3pp higher had it not been for the subsidies.

The impact of the subsidies is fading, such that new home prices should snap back by about 3.5%.

The effect of these government subsidies is fading as fewer payments are made, such that a 3% underlying increase in new home prices in Q3 was fully reflected in the CPI that quarter.

When the subsidies are exhausted, their earlier restraining effect will be reversed and new home prices are likely to snap back by about 3½% to their ex-subsidy level. Given their large weight in the CPI, this means that new home prices will add about 0.3pp to headline inflation over the next few quarters.

Longer term, though, the boost from construction costs should unwind when supply constraints ease both in Australia and abroad.

Underlying inflation would have been around the midpoint of the 2-3% target band had it not been for the housing subsidies.

Calculating the impact of the subsidies on the RBA’s preferred measure of underlying inflation is less straightforward because the trimmed mean CPI depends on the distribution of price changes, “trimming” the most extreme price changes.

Constructing a version of the trimmed mean CPI that uses home prices excluding subsidies and reweighting the CPI basket accordingly, annual underlying inflation was 1.3% in Q4, increasing to 1.8% in Q2 and to 2.6% in Q3. This is much higher than the published, including subsidies, series, which showed annual inflation of 1.1%, 1.6% and 2.1%, respectively.

This suggests that underlying inflation would have been significantly higher had it not been for the restraining force of the subsidies, although to be fair, housing costs would probably not have been as strong in such a counterfactual because the subsidies brought forward an enormous amount of demand.

Underlying inflation could average 2.25-2.5% in the first half of 2022.

Although new home prices should snap back as the last of the government subsidies are paid, they are unlikely to have a direct effect on underlying inflation. This is because the trimmed mean CPI automatically excludes large price movements and actually excluded the large increase in new home prices in Q3.

To sidestep this issue, we constructed a version of the trimmed mean CPI that excludes new home prices altogether. This shows quarterly inflation of 0.5% in Q1 and 0.6% in both Q2 and Q3, with annual inflation of 2.1% in Q3.

Assuming this momentum – which is the strongest in years – is maintained, annual underlying inflation, including rebounding new home prices, could average around 2¼-2½% in the first half of 2022.

Longer term, an eventual correction in housing costs should weigh on underlying inflation providing the correction is drawn out (a sharp correction would risk being trimmed out of the calculation of underlying inflation).

Higher underlying inflation would raise the possibility that there is less spare capacity in the labour market than previously thought.

Analysis suggests that the main reason underlying inflation has undershot the RBA’s 2-3% target band over recent years has been spare capacity in the labour market, with the unemployment rate holding above a slowly declining NAIRU.

The RBA’s inflation model suggests that after reaching a multi-year low of 4¾% the NAIRU has ticked up to 5% this year, albeit that there is a large confidence interval around this estimate. In contrast, Governor Lowe suggests the NAIRU may have fallen to the low 4s and may be in the 3s.

While more data, including wage data, will be required to get a better idea of spare capacity, the fact that underlying inflation excluding new home prices has picked up this year raises the possibility that either the lower-than-anticipated unemployment rate is giving a better read on the labour market than hours worked and/or the NAIRU may not be as low as believed.

This therefore underscores the importance of recent reports that the federal government is eager to ramp-up skilled migration in concert with willing state governments, which will be crucial to combatting skills shortages, and the ensuing wage pressures, as the labour market tightens.

The RBA's willingness to look past temporarily high wage and inflation prints as this potential surge in labour supply comes on line will in turn influence the interest rate outlook in 2022 and 2023.

3 topics