Countdown to zero? Vanishing listed infrastructure will drive a shift offshore

This financial year has been momentous for mergers and acquisitions in the ASX-listed infrastructure sector – and it's only October!

Three proposed M&A transactions have occurred in a very short space of time, with unlisted investors seeking to privatise some of Australia’s much loved publicly listed infrastructure companies:

- AusNet Services (ASX: AST),

- Spark Infrastructure (ASX: SKI), and

- Sydney Airport (ASX: SYD).

What does this mean for investors, and where in the world will they be able to find listed infrastructure assets?

The spate of proposed transactions demonstrates the insatiable demand for world-class essential infrastructure assets by private investors.

On current valuations, these investors are taking advantage of a compelling valuation arbitrage that presently exists between public and private markets — public markets are undervaluing infrastructure assets and this is making them ‘hot’.

While these transactions can be rewarding for shareholders should they occur, it also means that the ASX will have fewer and fewer essential infrastructure investment options.

This underscores the increasing impetus to seek global exposure to listed infrastructure, an asset class that continues to grow, despite the wave of M&A occurring Down Under.

What's the big attraction?

AusNet Services, Spark Infrastructure and Sydney Airport are each very attractive on global infrastructure benchmarks.

They are all high-quality infrastructure assets operating in attractive regulatory and commercial environments, with business models that have significant barriers to entry, and in some cases, absolute barriers to entry.

In the case of AusNet Services and Spark Infrastructure, both own highly regulated long-dated utility assets in Australia, with supportive regulation and long-term predictable cash flows, largely insensitive to the economic cycle.

Spark owns equity interests in regulated electricity distribution assets in Victoria and South Australia, and also an interest in Transgrid, the owner of the NSW electricity transmission grid. It also has some interests in renewable energy assets. AusNet Services owns electricity distribution and transmission assets in Victoria, and a gas distribution network.

Importantly, both are positively leveraged to the energy transition occurring across the eastern Australian energy grid.

These networks are critical to the decarbonisation of the grids, with significant investment required to support the transition from fossil-fuel-based generation to increase renewables, support grid stability, drive the uptake of electric vehicles, and encourage energy efficiency.

Sydney Airport is temporarily and severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated travel restrictions domestically and internationally.

This has caused a major disconnection between the long-term value of Sydney Airport shares and the trading share price prior to the take-over activity.

Faced with a high degree of uncertainty regarding the shape of recovery from COVID-19, equity markets can become short-term in focus.

Sydney Airport will once again become a pre-eminent global infrastructure asset once air travel begins to recover and governments progressively relax travel restrictions.

Sydney Airport is subject to attractive light-handed regulation, has growth potential in its aero and non-aero businesses and earns attractive returns on invested capital.

Private and pension capital have struck when share prices fail to reflect both the fundamental long-term values of these businesses and, in the case of AusNet Services and Spark Infrastructure, the long-term critical role regulated utilities play in the energy transition underway globally.

Why noted investors are paying above the odds

This trend in buying assets outright at takeover multiples is predicated on the idea that total control brings offsetting financial benefits, such as reduced listing costs, cheaper investor relations, direct control of asset development and expansion, and other potential reductions in common asset costs.

A 100% acquirer can typically install their own management team, strategy and capital structure in order to extract the maximum value possible, subject to regulatory requirements.

Listed investors are typically not as comfortable as unlisted investors with higher levels of debt, and this can impact the valuations of listed infrastructure companies, and their relatively under-geared balance sheets. This is a risk-benefit in our view, with respect to listed infrastructure.

Equity markets are a kaleidoscope of investors with different criteria, valuation metrics, risk appetites and timeframes. Equity market valuations of infrastructure companies can be affected by general market conditions and expectations, often a significant source of alpha opportunity for active investors.

In a ‘risk-on’ market with rising expectations for real GDP and inflation (a lot like recent conditions), listed infrastructure share prices may be relatively suppressed as equity investors chase easy beta and higher returns, even if long-term cash-flow-based valuations of the infrastructure assets are not materially impacted.

Over the cycle, the stable cash flows of assets reward infrastructure investors, and adjust for this short-termism in equity market valuation.

There is also a fundamental difference in the analytical tools deployed by infrastructure investors.

Generally speaking, equity market investors are more likely to use expected profits, cash flows and/or dividends in the next couple of years to value listed infrastructure across the entire market on a comparative earnings multiple basis.

Long-term infrastructure specialists, by contrast, take a lifecycle expected cash flows approach to valuing listed infrastructure that more accurately accounts for the long-term cost and income streams, and the complicated regulatory patterns that drive returns.

The specialists bring these back to a capital cost relevant lifecycle equity return, which is a more genuine and accurate measure of the value of a listed infrastructure asset.

Moreover, a typical mismatch in time frame between listed market investors and the unlisted infrastructure investors means that there is potential for a valuation arbitrage to exploit.

This gap is only exacerbated when near-term cash flows are severely impacted, as has been the case with Sydney Airport and Auckland International Airport from the impact of COVID-19.

Short-term profit and cash flow metrics simply do not capture the power and value of decades-long predictable cash flows.

Even in Australia, perhaps the most infrastructure savvy market in the world, listed investors miss this opportunity, a situation replicated to a higher degree in other markets around the world.

Why listed assets are rare and M&A agents are busy

The ASX-listed infrastructure space, at its height, had over 15 listed companies. Many of these companies were listed over the period spanning 1995 to 2010.

For example, Transurban was listed in 1996 with a single toll road concession: Citylink in Melbourne.

APA Group was spun out of AGL Energy in 2000 with ownership interests in four gas transmission pipelines in Australia.

Spark Infrastructure and AusNet Services were both listed as initial public offerings in 2006 by private owners.

The long-term lease to operate Sydney Airport was acquired by Macquarie Group, which in turn listed it through IPO, together with interests in some European airports in 2009.

Both APA Group and Transurban have embarked on significant M&A activity, including taking over listed companies and participating in sizeable M&A of other companies and assets in their respective areas of expertise.

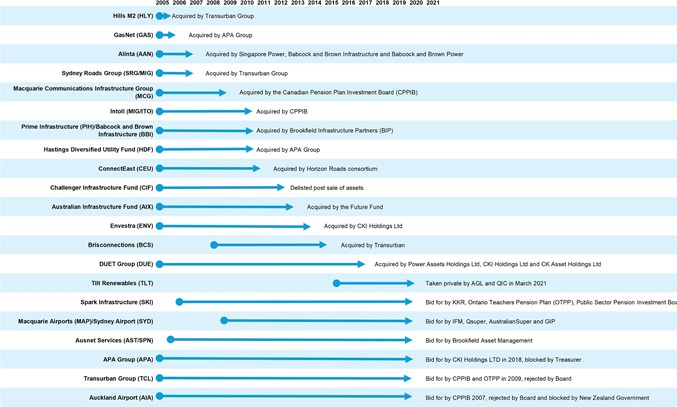

This chart illustrates

the path from over 15 listed infrastructure assets

towards none.

Evidence in the case of the vanishing ASX-listed infrastructure company

Source: Ausbil. Note that the dots show listing dates. As most listed before 2005, the starting dot is in 2005.

There has also been significant M&A involving other infrastructure companies like Asciano (transportation, sold to private investors and other port operators) and Infigen (wind farms, acquired by Iberdrola in Spain).

While neither of these assets meets Ausbil’s strict definition of essential infrastructure, they serve to demonstrate the demand for these and similar assets.

We are now seeing this with the super fund consortium seeking to acquire Sydney Airport, and offers for Spark Infrastructure and AusNet Services.

So what makes Australian infrastructure so enticing? There are numerous reasons for the high level of M&A activity in the Australian listed infrastructure sector.

Firstly, the regulation of utilities and Australia’s legal frameworks that apply to infrastructure assets, including concessions, are considered relatively stable and predictable on global comparisons. Property and legal rights are well defined, codified and protected in the common law.

Australia is one of the pioneering infrastructure markets. Our lenders and capital markets are among the most advanced globally in their reception and funding of infrastructure assets.

Moreover, most Australian infrastructure assets of any size can tap the global bond markets and are considered amongst the highest investment-grade assets, readily offering bond issuance in liquid USD, EUR and GBP bond markets if needed.

These ready channels for capital flow support the growth and expansion of infrastructure assets in Australia.

Secondly, in the great credit shakeout of listed trusts (both real estate and infrastructure) during the global financial crisis, some infrastructure trusts and companies over-levered their balance sheets, creating significant pressure on equity valuations and making themselves acquisition targets for savvy global institutions, private equity and larger peers.

Furthermore, while take-overs of critical infrastructure assets in Australia have become more challenging with a tightening of Foreign Investment Review Board rules in recent years, generally speaking, Australia has been viewed favourably in terms of the ability to successfully execute M&A and obtain the necessary regulatory approvals.

Finally, the market capitalisation of much of the ASX-listed infrastructure is more modest in size (especially versus, say, the North American utilities sector), making M&A more likely for global private equity giants, investors, pension funds and larger global peers.

What happens if ASX-listed infrastructure vanishes?

Assuming the Sydney Airport, AusNet and Spark transactions complete in one form or another, there will potentially be only four ASX-listed infrastructure companies that meet Ausbil’s essential infrastructure criteria.

These are Transurban (TCL), Atlas Arteria (ALX), APA Group (APA) and Auckland Airport (AIA, dual-listed on the ASX and NZX).

Two other listed infrastructure companies, Aurizon Holdings (AZJ) and Dalrymple Bay Coal Terminal (DBI), do not meet Ausbil’s strict definition of essential infrastructure and are excluded from our investment universe.

Should the proposed acquisitions of AusNet Services and Spark Infrastructure succeed, there will be no listed regulated utility on the ASX. There is no listed mobile phone tower company on the ASX, with the recent sale of 49% in Telstra’s towers going to the Future Fund and various super funds.

Moreover, following the takeovers of Infigen and Tilt, there is no pure-play renewable energy company listed on the ASX, leaving the only options for pure-play renewables exposures in offshore companies, such as global renewable powerhouses like NextEra and Ørsted.

However, there is no shortage of essential infrastructure companies listed on stock exchanges in investment-grade developed markets.

Globally, the listed infrastructure sector is set to grow larger as new government-owned assets hit the boards, older companies spin off infrastructure portfolios (such as Acciona Energia and Vantage), non-essential infrastructure is divested (such as DTE and PEG), private equity listings crystalise profits or trim portfolios, and because of the options public listings offer infrastructure equity holders.

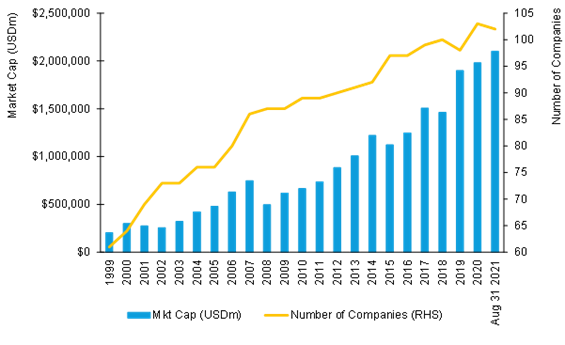

This chart illustrates the combined market capitalisation of Ausbil’s essential infrastructure universe, which has grown from around US$200 billion in 1999 to over US$2 trillion today.

Ausbil’s global essential infrastructure universe has grown with a compound annual growth rate of 13% since 1999

Source: Ausbil

The answer to the crisis of vanishing Australian listed infrastructure is simple: invest in global infrastructure.

A portfolio of global essential infrastructure companies allows investors to achieve their required diversification across quality toll roads, airports, mobile phone towers, energy infrastructure, regulated utilities and renewable energy companies.

Global markets offer the full potential for participating in the compelling secular growth offered by the energy transition, 5G and the internet of things.

Global infrastructure offers the opportunity to exploit valuation discrepancies that can exist from time to time between regions and sectors.

With a complete opportunity set of listed infrastructure assets across all the key sectors, across multiple markets, investors can fully capture the true characteristics of the infrastructure asset class, such as:

- Downside protection when equity markets fall.

- Low correlation to global equities.

- Relatively stable returns through the economic cycle.

The shrinking listed infrastructure sector in Australia just serves to underscore that the full opportunity in the essential infrastructure asset class awaits offshore for those who are keen to capture its benefits.

Invest in stable cash flow assets

Ausbil invests in securities that have assets that are essential for the basic functioning of a society. To find out more, click the 'FOLLOW' button below.

3 topics

8 stocks mentioned