Credit Availability IS Australia’s House Prices

I have a friend who is mildly wealthy but not gainfully employed. He has been a customer of the same bank for the past 40 years. Like me, he doesn’t own a house. Unlike me, he has been thinking about it.

So he rolled into his local bank branch recently and asked to have a chat with someone about a potential mortgage. The staff member pulls up his details, sees a bit of cash in the account and tells him he’s in the wrong place. “You, my friend, should be talking to our High Net Worth division.”

A couple of quick phone calls later and my friend is heading to a swish HNW setup in Sydney’s Barangaroo towers. Do you need a parking place, sir?. It’s ok thanks mate, I’ll be getting the train.

Apart from a fancy coffee, he didn’t leave with much. The conversation went something like this:

Bank employee: So I hear you are after a mortgage loan?

My friend: Well, maybe.

Bank employee: How much did you earn last year?

My friend: As salary, not much. I don’t have a full time job. But if I bought something I would only be looking for a small loan relative to the value of the house.

Bank employee: But you must have a tax return or something?

My friend: Yes, I’m sure I can find one of those.

He digs around on his laptop for a while and finds last year’s tax return showing total income of roughly $26,000. Here you go Mr HNW manager, $26,000!

Bank employee: But we can’t lend you anything against that?

My friend: Well I’m not expecting you to. I’m only planning on borrowing 20-30% of the value of the house. You will have plenty of security.

Bank employee: I’m really sorry, but that’s not the way things operate. Without income, we can’t lend you money. Ciao for now.

That was the end of the meeting.

Credit the only thing that matters

It is not surprising that income is important. Obviously someone who earns a lot should be able to borrow more than someone who doesn’t. What is surprising (to me at least) is that it is the only thing the banks care about.

Ten years ago, my (naive) understanding was that a potential home buyer’s first step was to find a house they wanted to buy. Let’s say it was worth $1m and they had saved a $200,000 deposit. Then they would go to the bank, the bank works out whether they can afford to repay an $800,000 loan and respond yay or nay.

I had the process completely the wrong way around. The starting place is a bank (or mortgage broker). The bank assesses the customer’s income, decides how much they can lend against that income, then the borrower goes out and buys whatever they can with that amount of credit.

While banks tell their shareholders all about loan to value ratios and how much security they have, they don’t lend against the value of houses. They lend against people’s incomes. And the amount that they lend is the sole determinant of the “value” of Australia’s housing stock.

On a recent call, UBS analyst Jonathan Mott summarised the situation perfectly:

“House prices are not driven by the demand and supply of housing and population growth. Maybe on a 20-year time frame they are. House prices are determined by the demand and supply of credit availability. When you take your hand down at the auction is when you run out of money. And if the banks aren’t lending you as much as they did 12 months ago, well your hand comes down a couple of hundred grand lower”.

If credit is the sole determinant of house prices, what drives the provision of credit?

Income and interest rates

First, incomes. If incomes grow, banks can lend more money. But there hasn’t been much of that for the past decade. So it can’t have been the main factor driving more debt.

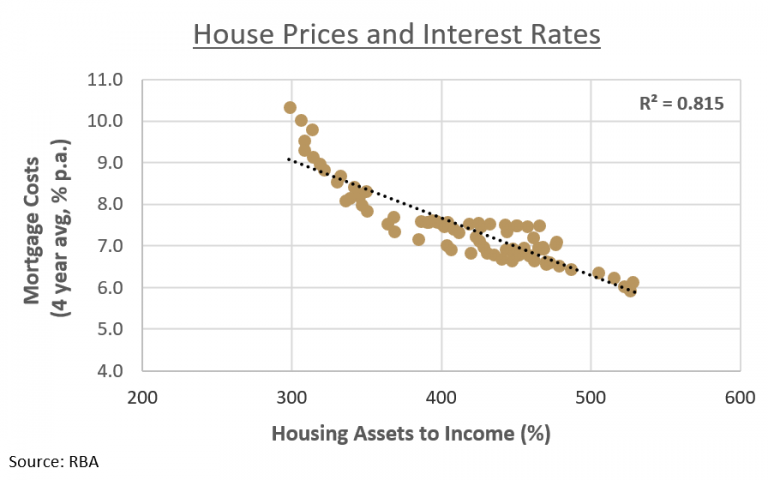

Second, most importantly, interest rates. Here is a chart we’ve put together using data from the RBA. It shows Australia’s house prices, measured as a multiple of disposable incomes, plotted against average mortgage costs over the previous four years:

Statistically, you can explain 81% of the change in house price multiples over the past 20 years by changes in the average cost of borrowing. They are almost the only game in town.

Almost.

Important exogenous lending factors

The final factor is any exogenous impact on the multiple banks are willing to apply to a person’s income at any given interest rate. Interest rates aren’t rising, incomes aren’t falling. But house prices do seem to be going down. And the reason is that these exogenous factors are very prominent at the moment.

Regulatory pressure and a royal commission into the banking sector has curtailed the amount the banks are willing to lend at low interest rates.

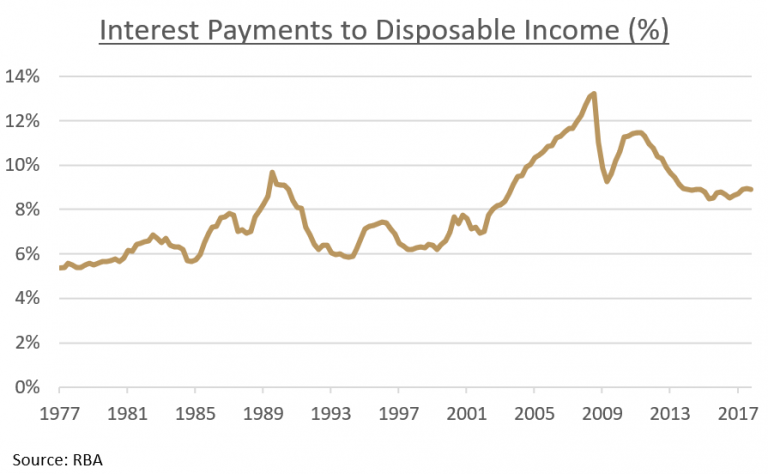

No doubt there are many individual outliers but the chart below shows interest costs as a percentage of disposable incomes across the entire country. As you can see, there is nothing here suggesting a problem. Servicing our debt is costing roughly the same percentage of income as it was 20 years ago.

But the regulators (rightly, in my opinion) are worried about banks assuming interest rates will stay lower forever. For several years they have had to stress test a borrower’s capacity to service their mortgage at a 7% interest rate, more than 2% higher than today’s levels.

It’s hard to fudge the 7%. It’s not hard to fudge the income. The royal commission has uncovered countless examples of absurdly low estimates of living expenses artificially inflating the capacity to service a loan at much higher interest rates.

Forcing them to use 7% and actual living expenses is going to seriously curtail the amount someone can borrow.

And just because you can service the interest doesn’t mean you can repay the principal. A newer, more restrictive regulatory restriction is that banks can now only lend up to six times their gross income. That removes removes living expenses from the equation. And it provides a cap irrespective of how low interest rates go. It will be particularly restrictive for multiple property owners who have been parlaying their equity into more and more properties.

Implications for house prices

It is clear that today’s marginal buyer has less access to credit than they did 12 months ago. That arm at the auction is coming down earlier and you are already seeing it in the official house prices. It explains why Sydney is suffering more than anywhere else. Six times your income won’t buy you much in the harbour city, whereas it still gets you a house in Hobart.

UBS anticipates a 5-15% fall in the short term and I don’t see any reason to argue with it.

For more dramatic falls, though, you would need to see interest rates rise, incomes fall via rising unemployment or a change in the Australian psyche.

While I don’t see any of those as imminent, the days of house prices rising faster than incomes are over. Interest rates are not the binding constraint at the moment, so further cuts won’t make any difference. If six times income is the cap on lending, six times income will be the cap on prices.

That, for much of the country, is going to take a lot of getting used to.

Further insights

If you are interested in receiving the Forager monthly and quarterly reports, please register here

4 topics

.jpg)

.jpg)