Cyclical turning point could provide important confidence boost

Australia's economy appears to be moving toward the change that many consumers and business have been hoping for as interest rates are stabilising and consumer spending appears well under control. Attention is focused on inflation, with hopes that it will return to the RBA's target range within the short term, and jobs data which is holding firm at 4.2 per cent. With this, there is renewed hope across the property sector but particularly for residential property development as its expected that falling rates will bring new buyers and increase buyer affordability to allow developers to gain sales and ultimately finance for projects that have stalled.

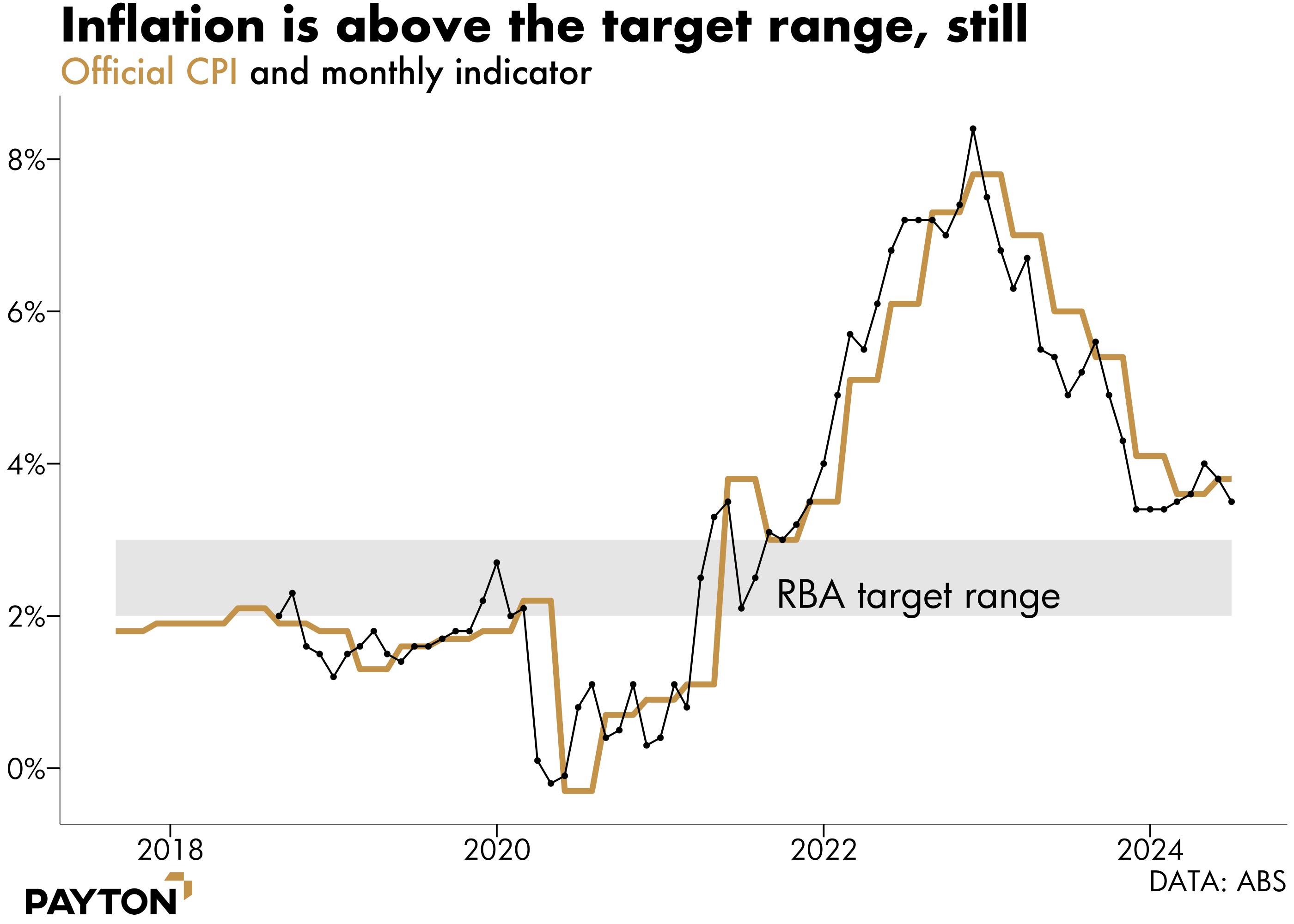

The level of inflation the RBA strives for is in between 2 and 3 per cent, which appears to be a goal within reach. Both Westpac and Commonwealth Bank have recently released economic reports anticipating the monthly inflation rate will show a fall to 2.7 per cent per annum over the year to August.

Key factors contributing to this decline include electricity rebates, decreasing prices for petrol and a reduction in food cost. The consumer market is showing signs of stabilisation, as global commodity prices normalise, and domestic businesses find it difficult to raise prices in the face of consumer reticence. We believe this is cause for (cautious) optimism.

What have we seen

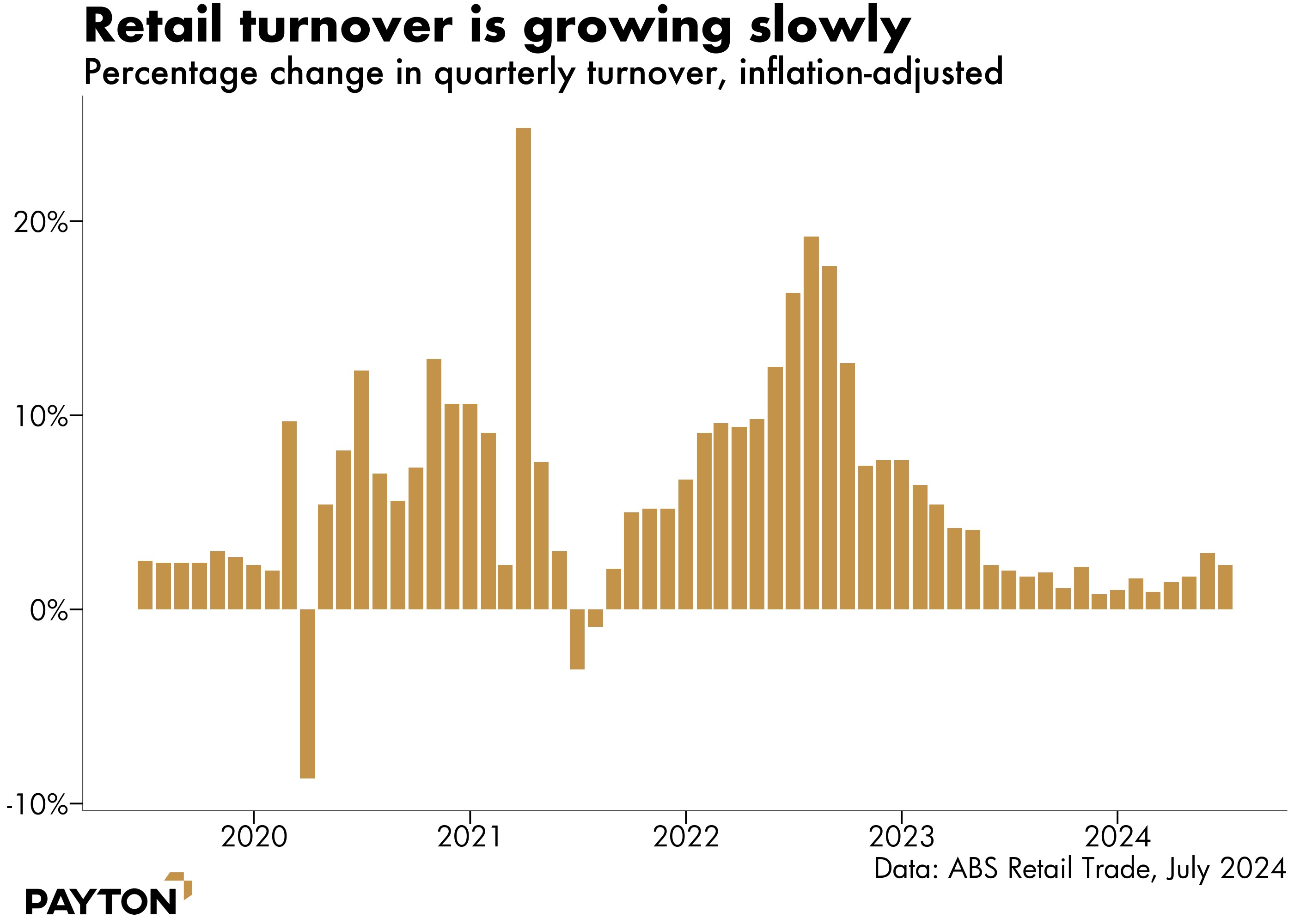

Australia’s monetary policy to date has been successful in suppressing consumer spending. The RBA’s intended effect has been achieved; overall consumer spending is growing slowly despite high levels of population growth.

As the next chart shows, growth has remained positive across recent months in aggregate, but only barely. The chart sums across discretionary and essential spending, and it is the latter which is growing more quickly. Households are cutting budgets where they can and spending only where they must.

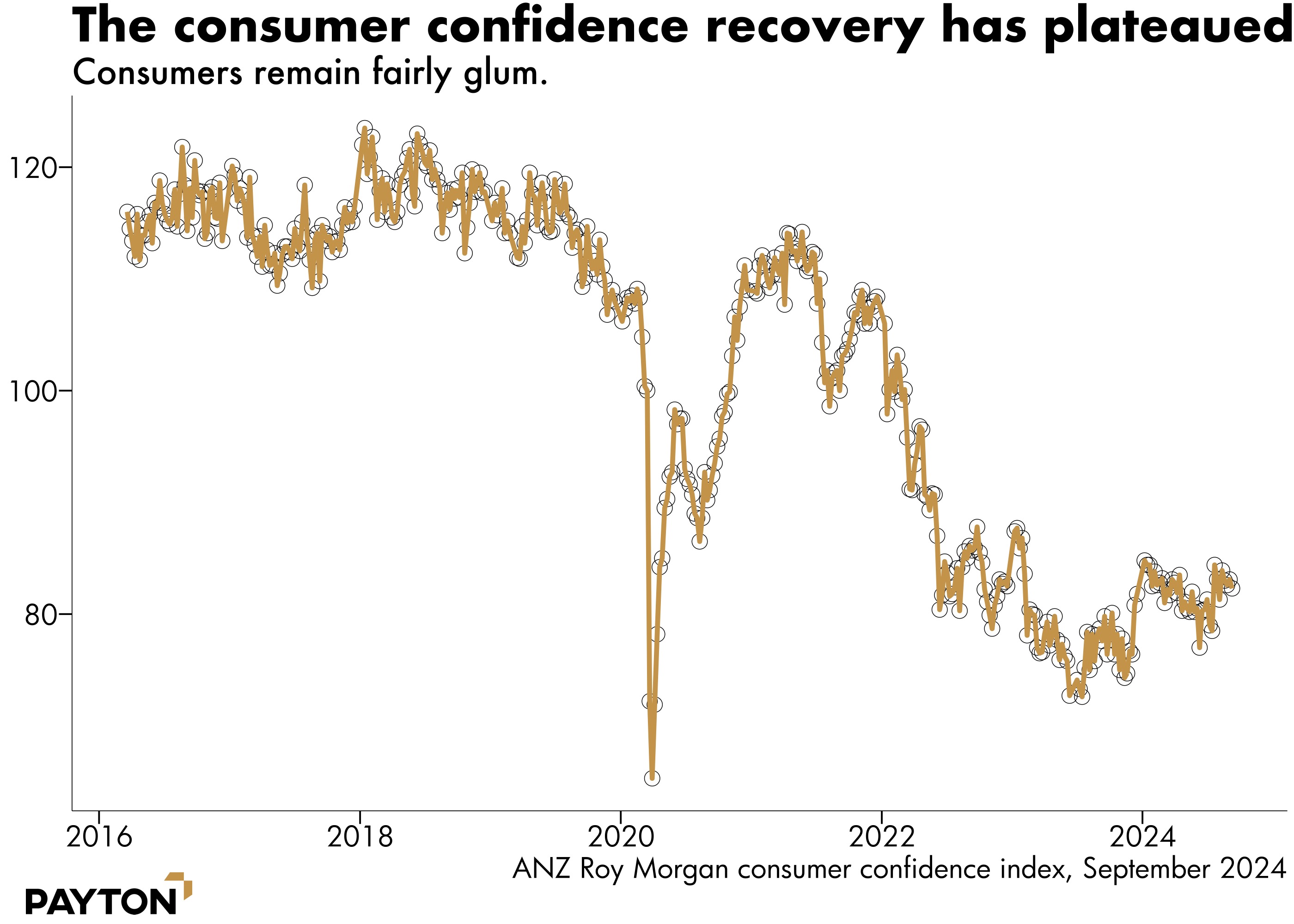

The slow rate of retail spending growth aligns with survey findings on consumer confidence. Australian consumers have yet to regain their pre-pandemic optimism. The most we’ve observed is a slight increase from the lowest points, which has plateaued throughout 2024.

Despite these concerning numbers, there is a glimmer of hope. The subdued consumer activity suggests that high inflation may be nearing its end, potentially paving the way for the RBA to consider lowering interest rates sooner.

Of course, we will not see consumer confidence rise immediately when inflation is deemed to be controlled. The rate of change in retail prices has returned to normal recently, as measured inflation moves from the supermarket aisle to the services sector – insurance, rent, education, medical etc. Consumers do not measure inflation in the same way as official statistical agencies. While the Australian Bureau of Statistics will tell you that dairy prices have only risen by 2.3 per cent since this time last year, shoppers will tell you that prices are up 50 per cent or more since the start of the pandemic.

In short, consumer perceptions of inflation will take longer to abate than actual inflation, and so there is likely to be a lag between the technical defeat of inflation and the popular sense that inflation has been overcome. Nevertheless, the RBA can act as the end of inflation comes into view, and that in turn can inspire consumers to higher levels of confidence.

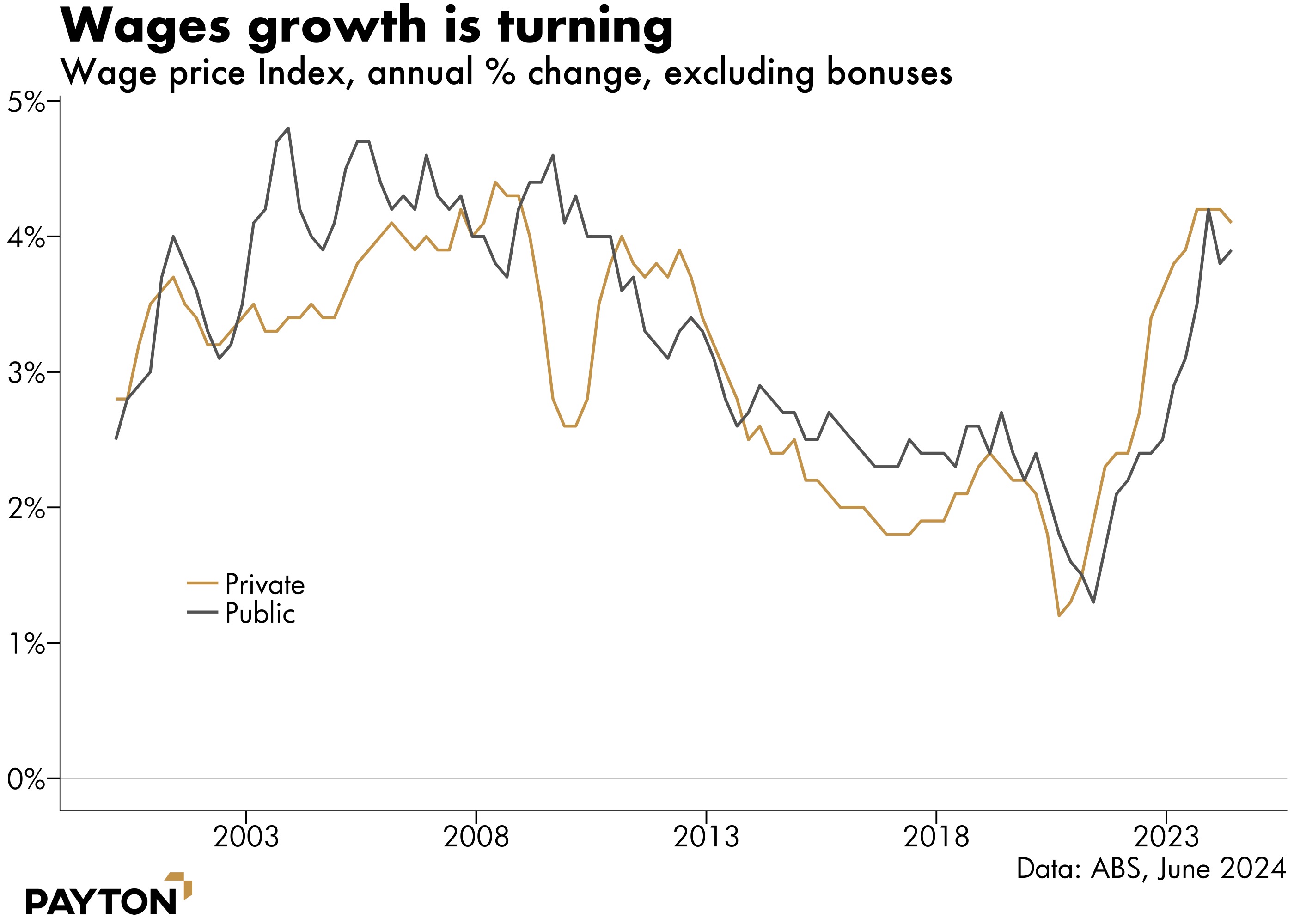

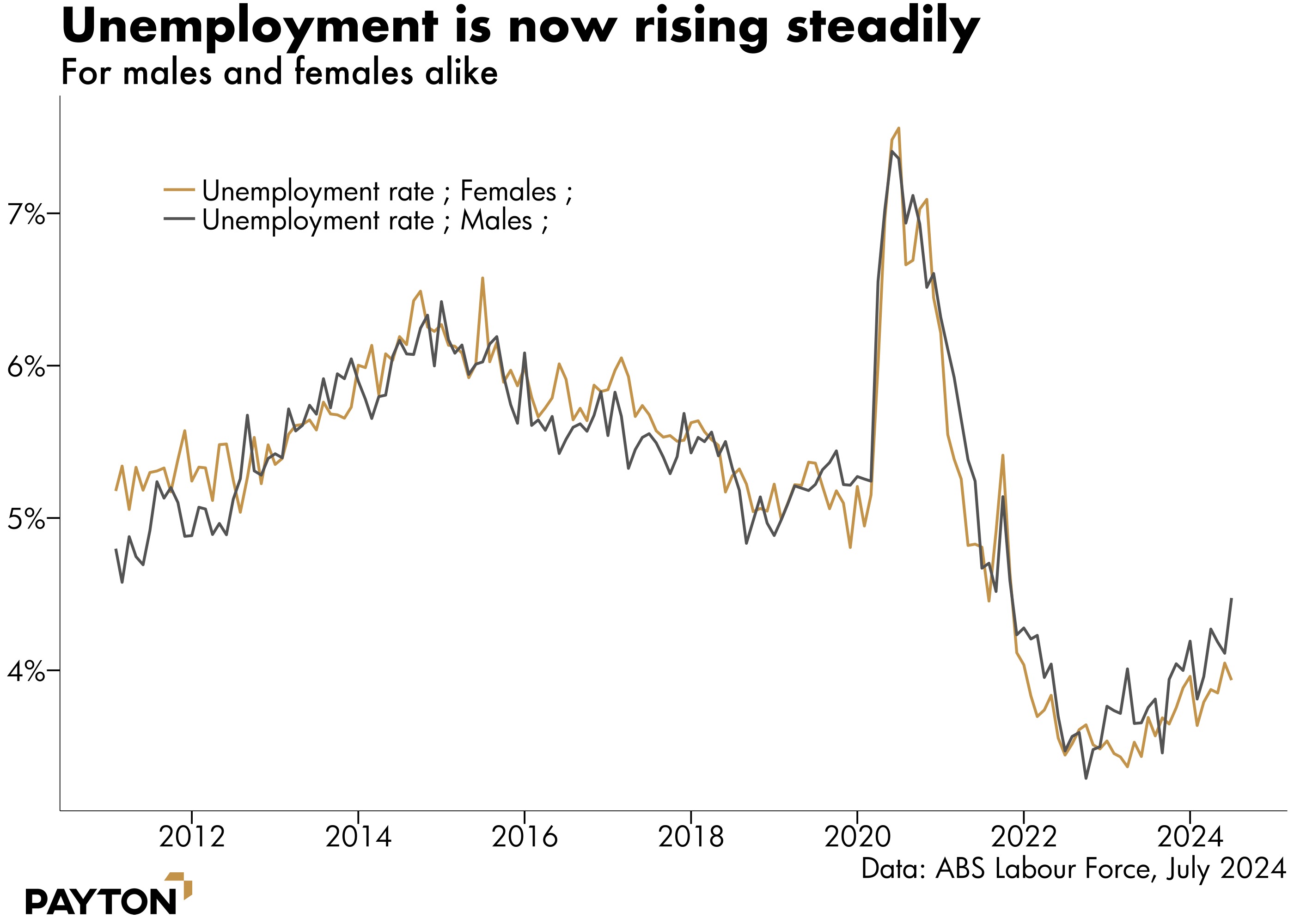

The consumer despondency story is rounded out with unemployment and wages. Wages growth has flattened out, as unemployment rises. From the RBA's perspective, these figures are encouraging. They aim to temper the robust job market without causing a significant downturn or allowing unemployment rates to rise quickly.

“[A]s labour market conditions ease, more households will experience a strain on their finances from unemployment or reduced working hours,” said RBA boss Michelle Bullock in a September address.

The RBA has a dual mandate to pursue full employment while defeating inflation, and Ms Bullock explains they intend to hold on to “as many of the gains in the labour market that we have seen in the past few years as possible.”

However, what does that look like in practice? We have certainly bid goodbye to an unemployment rate that begins with a 3. Now an unemployment rate closer to 5 per cent is more likely to eventuate and be seen as a stable measure of a healthy economy.

The RBA’s commitment to keeping unemployment low is not without caveats. “Ultimately, though, it is crucial to remember that our full employment goal is not served by letting inflation stay above target indefinitely,” Ms Bullock said in September. In short, they would be willing to see unemployment rise further if it allows inflation to come down.

Where are we now?

Inflation is itself showing some positive signs. While it remains above the target range, the two most recent monthly CPI indicator results were both heading in the right direction. While the monthly results are not a perfect predictor of the official consumer price index, which is released quarterly, they are often the best guide.

Even with a dip into the target range in August, inflation is unlikely to plunge back into the centre of the target range immediately. The RBA suggests it will return to target only at the end of 2025. One reason for this is the various electricity price subsidies that will expire in due course. Another is rental inflation.

Rental inflation is going to continue to push up CPI for some time. This will happen even though advertised rents are starting to show signs of slowing. The official inflation measure considers all rental agreements, rather than only those that have recently been advertised. Many rental agreements leap upwards only when tenants change. This means rental CPI includes many stable contracts and so reflects advertised prices with a lag. We need other prices to fall to make up for the drawn-out rise in the rent index.

What do we see?

If the rest of the world is any guide, a normalisation of inflation and interest rates will soon be upon us.

In the US, rate cuts are a reality, not just an expectation as they are here in Australia. The Federal Reserve has been seen by some as a step or two ahead of Australia’s central bank throughout the pandemic and the recovery. American inflation is back in the target zone and the US Fed lowered interest rates by 50 basis points at the most recent September meeting, easing monetary policy for the first time in four years.

In recent times, Australia’s inflation and interest rate trajectory has echoed that of the US, running just a few months behind. The actions of foreign central banks have been explicitly called out as justification for moves in Australian interest rates – the international environment is part of what determines our interest rates. Therefore, moves in the US will help to shape expectations of what happens next in Australia.

The fall in US official interest rates is predicted to proceed a broader fall in other global interest rates. As a result, we are already seeing lower bond yields and lower interest rates on deposit products. Australian banks have begun to cut interest rates on savings accounts, bonus savings accounts, and term deposits with durations of more than one month. As an example, the average one-year term deposit in Australia had a rate of 4.3 per cent in August, down from 4.55 per cent at the start of 2024.

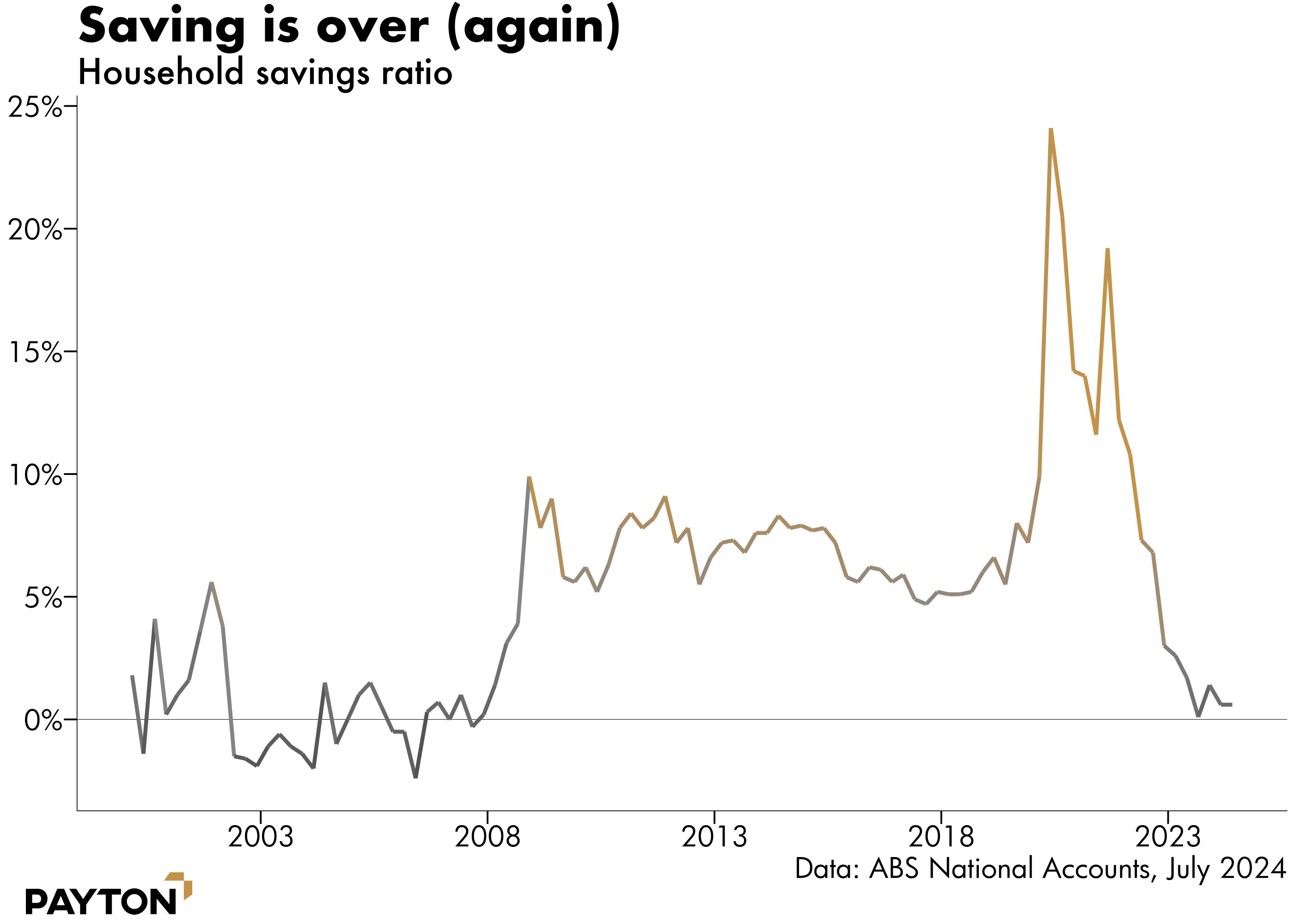

Falling rates are a bonus for borrowers but a burden for the thinning ranks of savers. Australia’s savings rate has done something very surprising. The rate plunged from the highs of the pandemic to basically zero, a level not seen since before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, as shown in the next chart.

Saving still appears to be occurring as demonstrated by the national accounts measure, but analysis by CBA (9 August 2024) suggests that the $300 billion in excess household savings (outside superannuation) that was built up by early 2022 will be exhausted by the end of 2024. This rapid run down of savings through the last year in the face of a cost of living crisis has helped to set the scene for a change in the economic climate. We could see a further slowdown in spending, with interest rates falling as inflation returns to the target range. That would be a climate in which we can expect to see more steady growth in residential house prices.

House prices in Australia are showing mixed trends. Prices are rising in Perth and Brisbane, remaining flat in Sydney, while Melbourne is seeing a decline. The Melbourne market is particularly affected by recent regulatory and taxation changes but will ultimately be lifted by higher levels of affordability that will eventually assist in raising Melbourne’s desirability for both interstate and overseas migrants.

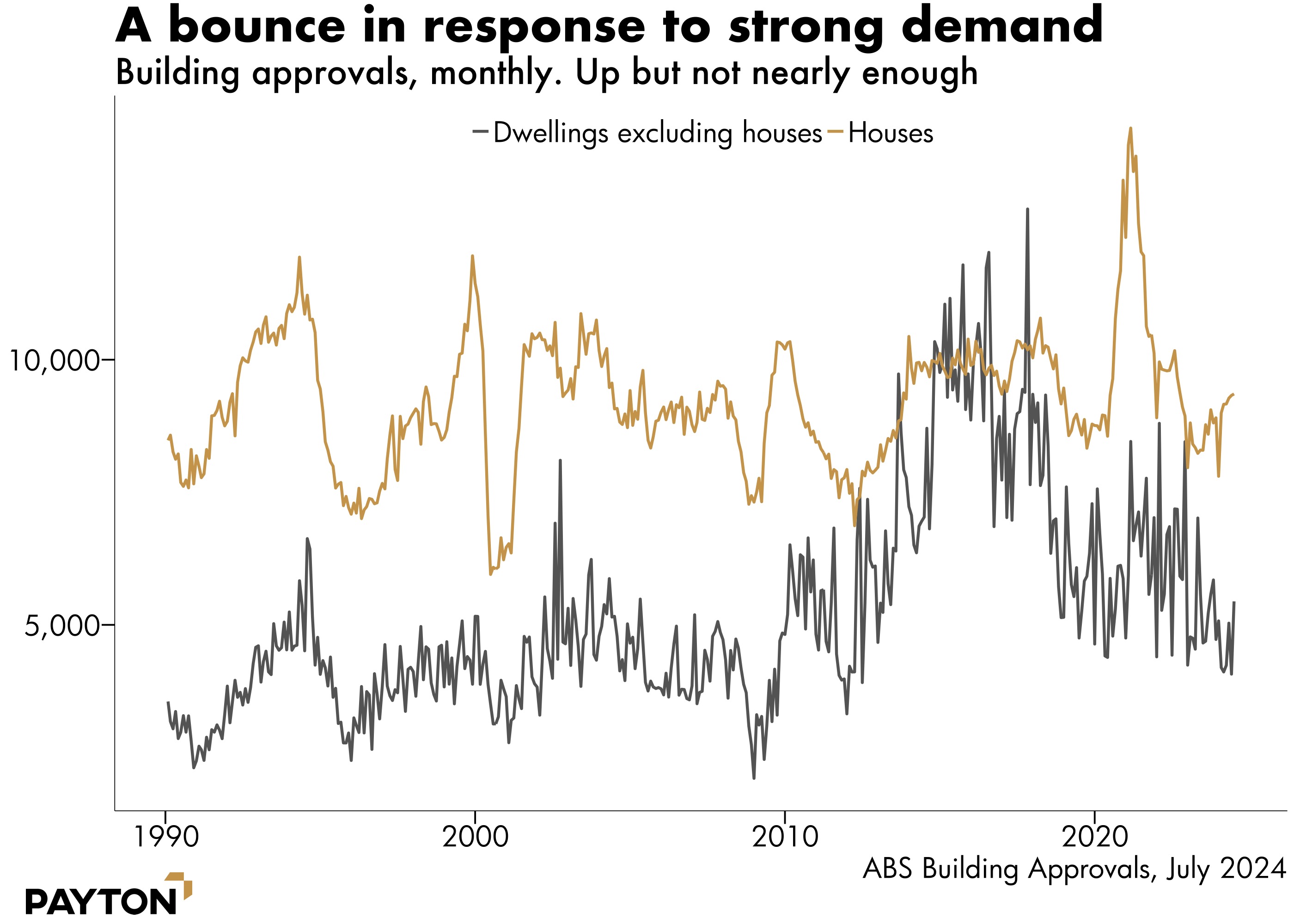

The housing market is subject to very strong demand for rental properties and a shortfall of homes. Amid both high input prices and labour costs, the building sector has been slow to respond. However, the most recent data thankfully shows a small uptick in building.

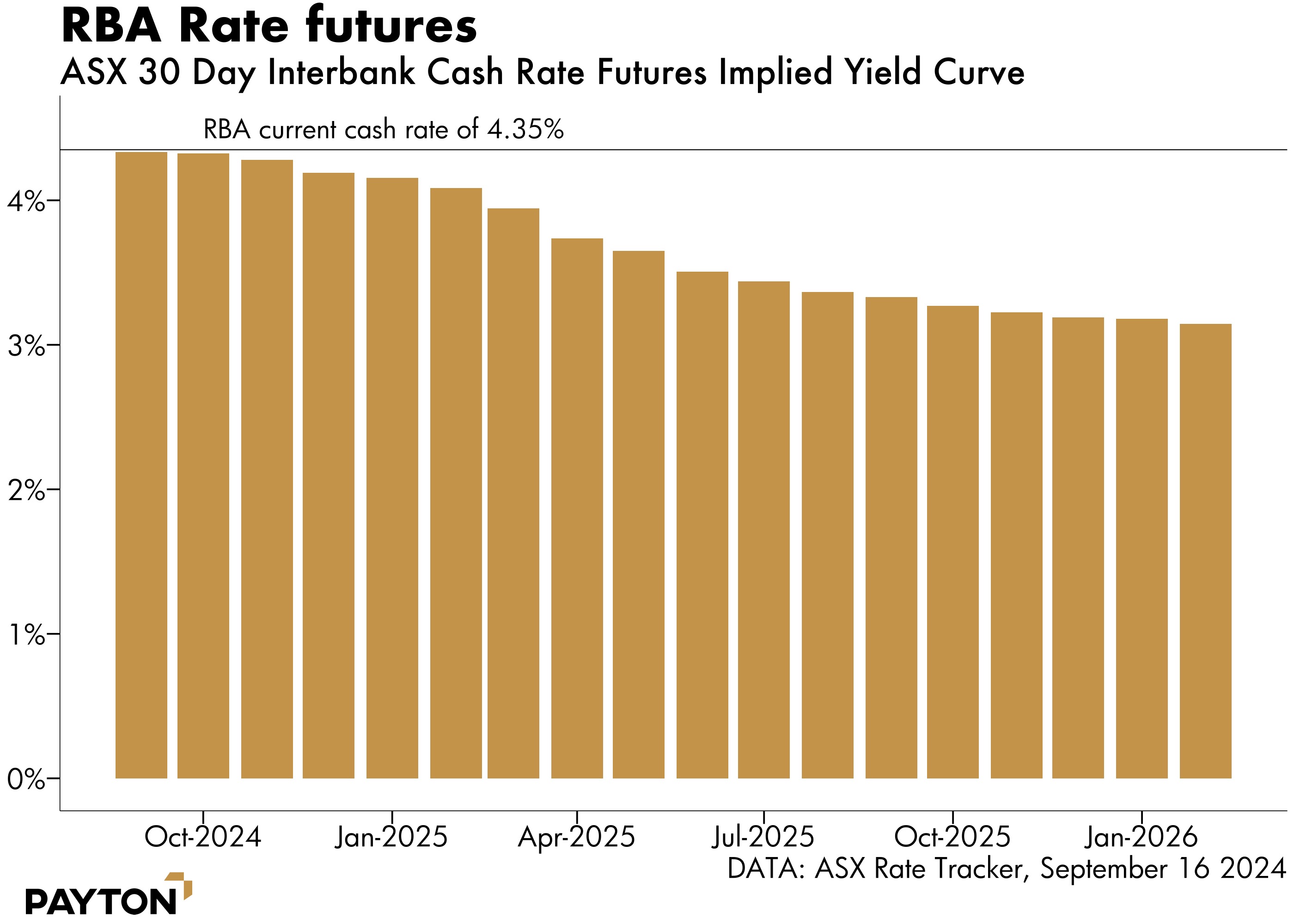

The uncertainty surrounding the timing of rate cuts has deepened due to the discrepancy between the RBA’s messaging and market expectation.

RBA boss Michelle Bullock has advised market participants not to expect rate cuts. “If the economy evolves broadly as anticipated, the Board does not expect that it will be in a position to cut rates in the near term,” she said in a recent speech.

But the market is keeping its own counsel. Futures imply that rates will be cut during this year. As the next chart shows, the market is pricing in rate cuts of at least 25 basis points by January 2025, and then steeper falls thereafter.

The outcome here is either the market thinks the RBA is “jawboning” (promising not to cut rates even though they may do so) or the RBA will update its views on the likely path of the economy. Ultimately only time will tell if rates fall in 2024 or 2025, however the expectation remains that the next move will be down.

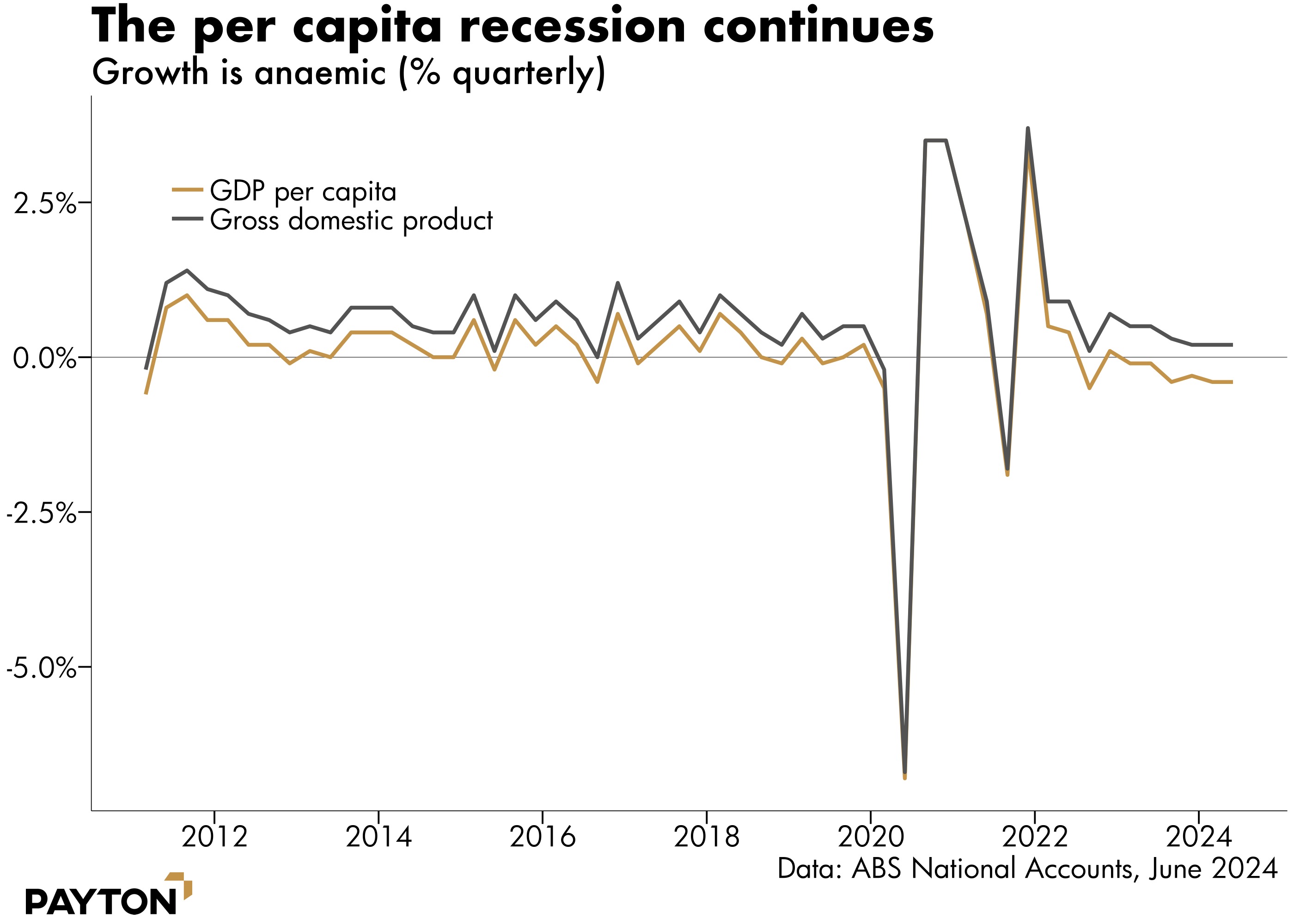

With economic growth low, public spending has emerged as the main reason the economy is not in recession. Certainly per capita growth is firmly negative, and per capita growth is the measure that matters most to households.

Aggregate economy is being held up by government spending. Household consumption detracted 0.1 per centage points from GDP growth in the most recent quarter while government spending contributed 0.3 per centage points, including social benefit and infrastructure spending. Public spending on capital formation is especially strong in the Northern Territory, South Australia, Victoria and the ACT.

In conclusion, the historical driving force behind the growth of the Australian economy has consistently been consumer spending rather than government intervention. Currently we are seeing that government spending is holding GDP growth, but this is likely to temper and the full effects of the slowdown will be evident. When interest rates begin to normalise and consumer confidence starts to recover, we anticipate a resurgence in consumer spending, which will likely reclaim its role as the primary driver of economic growth.

Current indicators suggest that we may be nearing a significant turning point in this economic cycle. In our view, the catalyst for this change will be the first interest rate cut. Such a move is expected to provide both consumers and businesses with the needed confidence boost to reinvigorate spending and investment. This renewed momentum could set the stage for a robust recovery, ultimately propelling the Australian economy forward and, in turn, supporting the upward trajectory of property prices. Private real estate credit markets are likely to see a softening of investor yields in line with the forward curve on interest rates, however still remain very attractive from a risk adjusted return profile.