Davos too gloomy on Globalisation

The yearly gathering of the worlds political and business leaders has just wrapped up in Davos. The theme for the conference was “creating a shared future in a fractured world.” Discussion on global trade took a decidedly downbeat turn. Much was made of the rise of extreme politics, with protectionist policies expected to slow globalisation. No doubt the intensifying trade conflicts of 2018 have raised the specter of a reversal of the post-World War II globalisation trend.

But we think this fear is exaggerated as most companies and countries continue to have a strong interest in maintaining (more or less) open markets. Moreover, we believe the US tariffs introduced in 2018 have so far been too limited to have a large effect, but the US has threatened more significant tariffs, in the absence of a negotiated settlement with China.

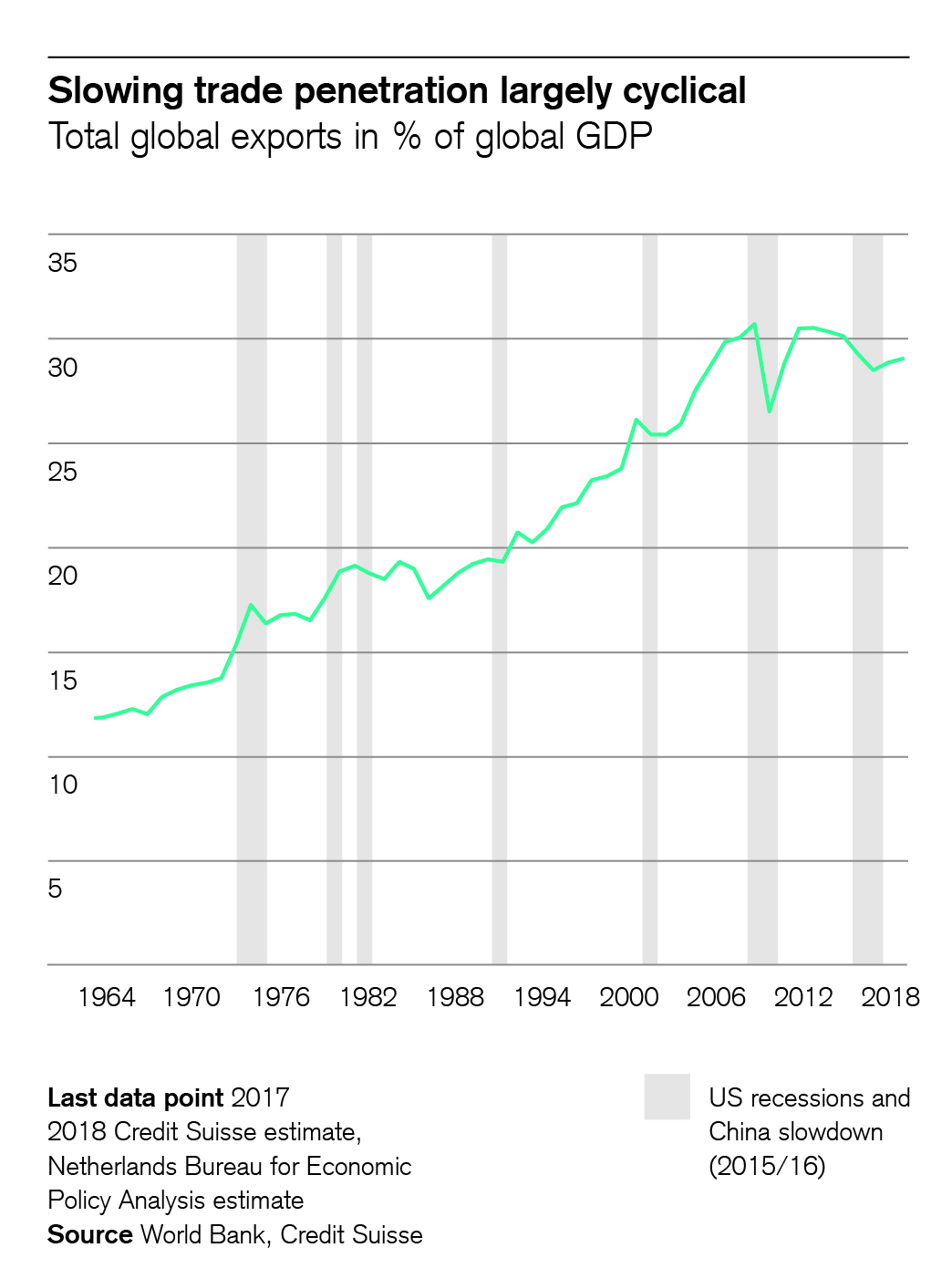

That said, our simple measure of globalisation (global exports as a percentage of global GDP) has stalled since the 2008 financial crisis.

There are two factors to explain the slowdown.

1. Firstly, there is a cyclical element to trade. Trade growth typically falls during recessions, seemingly halting the globalisation trend. This is what occurred during the Global Financial Crisis. Decreased economic activity often leads to big declines in commodity demand and prices, exacerbating the effect. The impact is again amplified as lower commodity prices reduce demand for mining-related capital goods.

2. The second factor at play is a phenomenon we have called “angry societies”, which is longer term in nature. Rising inequalities within Western countries and frustration over perceived or real failures of the political establishment to deal with current societal challenges, such as real wage growth, are leading disenchanted middle class voters to demand change. This brings to power governments with strong mandates for a policy more oriented to support the domestic economy, create jobs at home and address some of the pain points of the Western middle class.

Since the financial crisis of 2008, inequalities have grown globally, not so much among countries but within them, and especially in the developed world.

The economic policy mix of fiscal austerity and very loose monetary policy adopted in most developed economies to face the crisis, has proved particularly detrimental to the Western middle class. That is because the owners of capital (or assets) benefitted from Quantitative Easing, while fiscal policies did little to address the loss of income of wage earners. Outside of Australia, tough labour market conditions with persistently high unemployment and stagnating incomes following the economic recession were exacerbated by globalisation and disruptive technologies.

Technology is driving further inequalities as low skilled jobs are superseded. Many middle class households feel worse off - with good reason. In 1971 Credit Suisse estimates 60.8% of the adult population in the US could be considered middle income. Today we calculate the middle class is a minority in the US, but only just. The Australian middle class is not immune to this discontent. Unemployment is low at 5.0%, but according to the ABS, growth in real wages has been trending down since 2010, and has effectively been zero since 2016 despite the cost of necessities such as gas and electricity rising substantially.

Policy reactions to address inequalities are likely to be inflationary as governments attempt to increase wages or protect domestic industries. Typically, inflation becomes a negative for equities as markets anticipate rate rises. But, there are investments that can benefit from inflation such as commodities and inflation protected US treasuries (TIPS). In the USA, voters elected a political outsider as President, on the platform of breaking with political traditions. In this context, his actions can be considered rational. Raising tariffs are squarely aimed at protecting those industries where President Trump’s supporters work – agriculture and manufacturing, in particular.

This theme of angry societies is not a US issue alone, it applies globally.

But broadly speaking, at the country level, beneficiaries are companies with big brands who are seen as domestic champions, heavy manufacturers, local consumer product companies and interestingly internet security firms as corporates, and governments, seek to protect intellectual property.

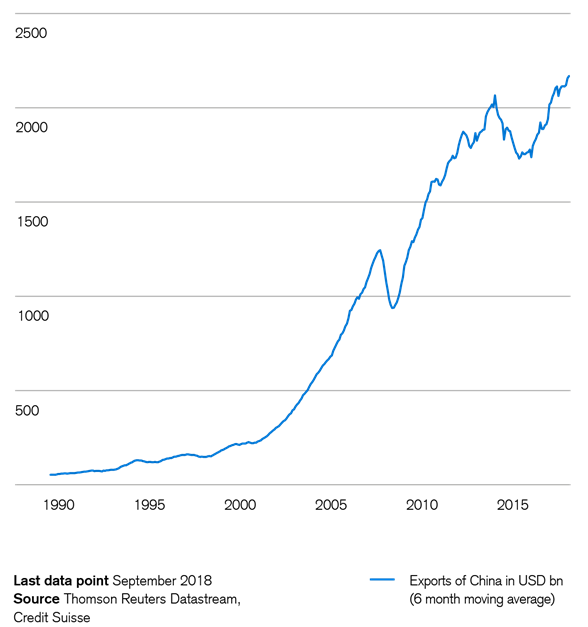

The US has applied a 10% tariff on USD200bn worth of Chinese exports to the US. China and the US have agreed to negotiate on trade issues, if no agreement is reached, the US plans to raise tariffs to 25%. The US has also held out the possibility of extending tariffs to cover an additional USD267bn of Chinese imports. The tariffs are negative for Australia, anything that impacts the Chinese economy, our largest trading partner, impacts demand for commodities such as iron ore and LNG. We estimate that if tariffs are raised to 25% this could reduce Chinese GDP growth by 0.9%. But the Chinese won’t sit on their hands, and will expand stimulus measures, such as the easing of credit conditions to mitigate at least some of the impact. Tariffs have had little impact on Chinese exports so far, which continue to rise.

Chinese Exports in USD bn

Overall, we believe globalisation is unlikely to return to a steep uptrend any time soon for various reasons.

Firstly, growth in China and other emerging markets that are strongly exposed to trade may be slower for longer. The tariff negotiations may take longer than expected, and the net result is likely to be a higher cost for goods delivered to the US.

Secondly, globalisation has been successful in raising millions out of poverty in developing nations. The clearest example of that is China as global production moved there in search of lower costs. However, the globalisation of supply chains may have at least temporarily stalled as wage costs have risen faster in some emerging markets to which production had been outsourced. For example, wages in China have risen to the extent certain manufacturing, such as textiles, has moved to Vietnam where wages are lower.

The investment implications of a slowdown in globalisation are hard to quantify. What is certain is it presents a headwind for Australian economic growth. With a large commodities export sector and small manufacturing and technology base, open and free international trade is to our net advantage. No doubt we would benefit from a more diversified economy in the future. The growth in the education sector is a positive case study of Australia playing to an international strength. We need to identify more examples like this if we want to insulate Australia from issues effecting global trade over which we have no control.

Never miss an update

Stay up to date with the latest news from Credit Suisse Private Banking by hitting the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire. Want to learn more about Credit Suisse Private Banking? Hit the 'contact' button to get in touch with us.

Credit Suisse Private Banking specialises in asset diversification, holistic wealth planning, next generation training, succession planning, trust and estate advisory, philanthropy. Find out more here