Debt in China and the Game of Pass the Parcel

Not many people outside of China have heard of the province, Guizhou. It is a landlocked province, and its main industry is agriculture. The Lonely Planet describes it as a secret province, where you can find “genuinely old villages” and “unspoilt mountains”.

A few weeks ago, the Guizhou government took the unusual step of publicly asking Beijing for assistance in resolving its debt issues according to media reports. There have also been signs of financial distress through one of Guizhou’s local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), a mechanism that allow local governments to borrow off their balance sheet, usually for the purpose of financing infrastructure projects. According to other reports, a restructure of bank loans owed by State-owned Zunyi Road and Bridge Construction Group (a LGFV) in the Guizhou province, was announced earlier this year.

These events are a rare public display of trouble with local government finances.

Just as with any default, it raises the question, how systemic is this issue? And just how big is this problem of local government debt?

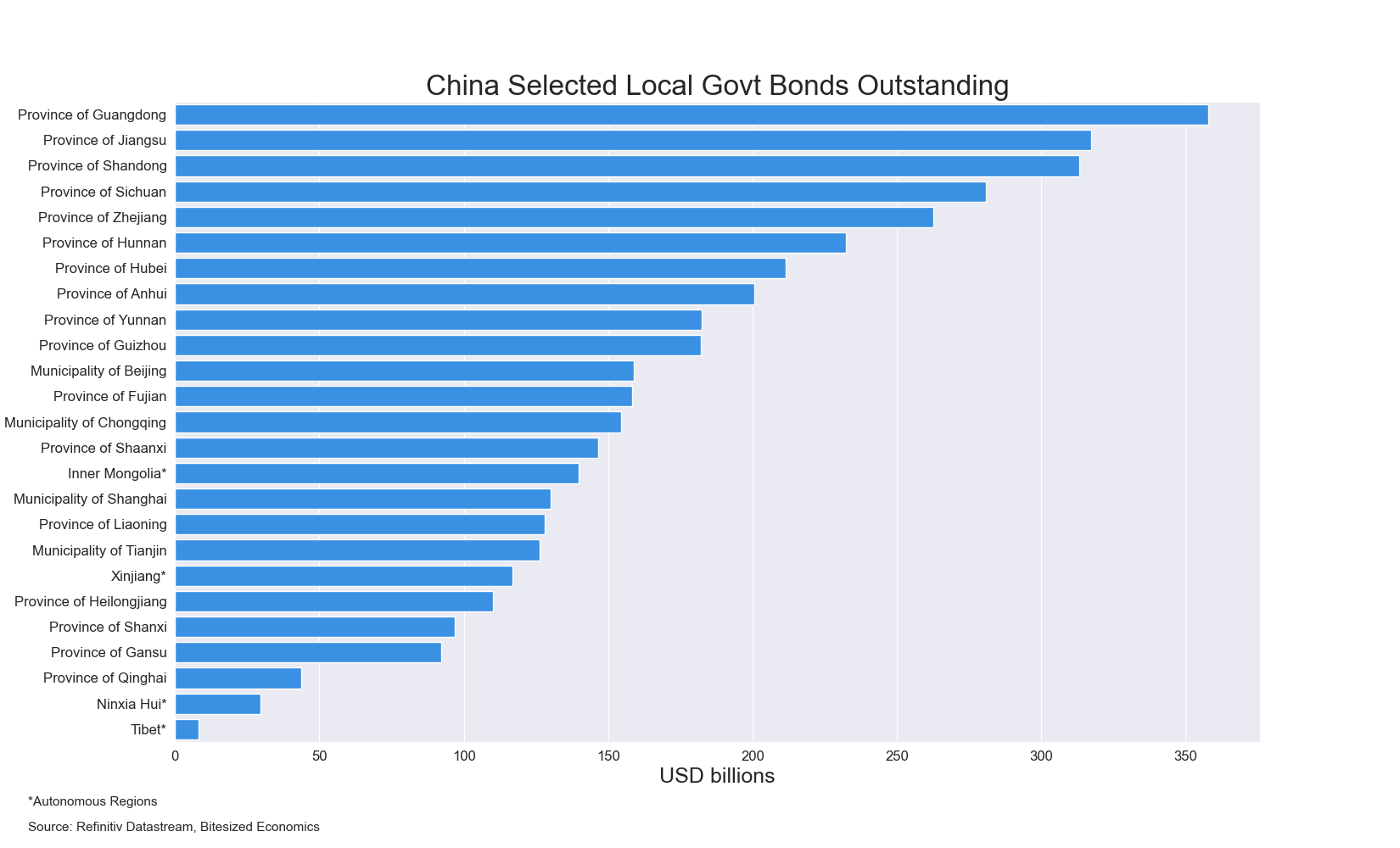

Official local government debt sits at around 25% of GDP, but LGFV debt is estimated at around 40% of GDP according to the IMF. That would equate to 70 trillion RMB of debt (approximately US$10 trillion) associated with local governments.

While these seem like big numbers, as a percentage of GDP, they appear less worrying and not too dissimilar from other advanced economies. When including official central, local government and other off-balance sheet forms of debt, China’s total government debt is estimated at around 100% of GDP. By comparison, government net debt as a percentage of GDP in the UK and the US is around 97% and 98%, respectively.

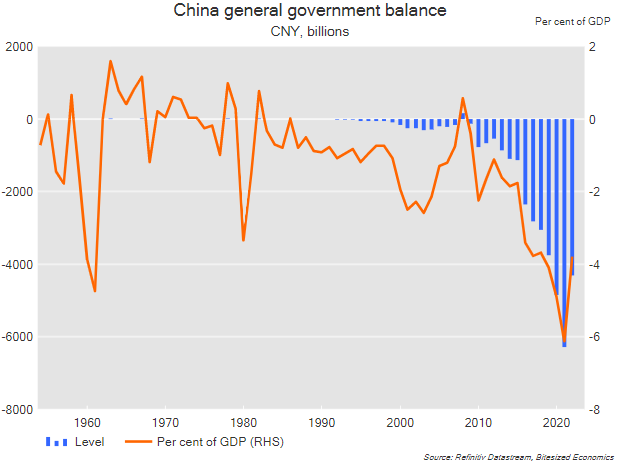

But high debt burdens become a problem when the trajectory of that government’s finances is unsustainable. For China, there is another issue and that is because local government debt has played a major role in supporting economic growth through financing infrastructure projects. Challenges in this area also places China’s growth model into jeopardy.

In the 2023 Government Work Report, Li Keqiang recognizes risks in relation to the fiscal position of local governments, noting that “the budgetary imbalances of some local governments were substantial” and that the government should work to reduce existing debt.

Not all local governments would be in the same kind of financial difficulty – the wealthier Guangzhou province and Shanghai Municipality are not in the same boat as the less affluent Guizhou province. However, it has been no secret that some provincial-level governments have been facing financial stress. The crackdown on the property sector, beginning back in 2020, hit a key revenue source for local governments. Then with covid, other revenue streams dried up further, and local governments had to pay for the measures to reinforce the zero-covid policy, such as covid testing. What’s more, is that LGFVs have played a role in supporting the property sector by purchasing land at above market rates over the past year. Note that land sales revenue has been a major income stream for local governments, so essentially governments have been buying back land and property through their LGFVs.

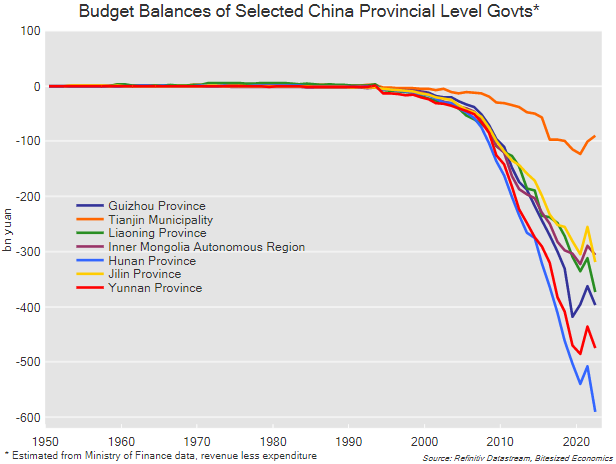

Budget deficits have widened, and in particular for some of the less wealthy provinces as shown in the chart above.

The Implicit Government Guarantee

For Guizhou, Stated-owned distressed debt manager China Cinda Asset Management has stepped into to assist the provincial-level government, to what will likely form some type of bailout plan.

This potential need for a bailout shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise – for many years there has been an assumption that the central government will step in and bail out troubled sectors or companies, particularly if they are state-owned.

Guizhou is not just a State-owned enterprise, it is a provincial-level government. Guizhou’s debt pile is also not small – its debt outstanding sits at around US$180 billion, and this doesn’t include debt through its LGFVs and other hidden debt.

It also reinforces the assumption that the central government will support local governments if they come into financial difficulties. While defaults have occurred more frequently in China’s State-owned sector in comparison to earlier decades, the government is still expected to step in when it comes to any failure which might cause systemic financial instability, even if it is indirectly.

A good example is how State-owned banks stepped in to lend to property developers in the aftermath of the Evergrande failure, and also indirectly by lending to LGFVs to purchase land.

Another example is in the wake of the Asian financial crisis. Four entities were set up (including China Cinda Asset Management) in 1999 to take on the bad loans of the four major banks in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis. One of these bad asset managers was Huarong asset management, which itself required a bailout just under two years ago, led by Citic Group, another State-owned asset investment company.

Too big to bail, and too big to fail?

At first glance, passing the bad debt along to another State-owned entity might seem like the obvious solution for any troubled local government debt.

However, there is one glaring problem – and that is whether the central government and the rest of the economy can absorb the non-performing debt. Not all the US$10 trillion LGFV debt is bad, and no one knows exactly how much is built on productive infrastructure with adequate returns on investment. But that uncertainty, along with the knowledge that local governments were incentivized to meet GDP targets over investing in financially viable projects suggests that this is not likely to be a small problem.

If the central government were to force State-owned banks and other entities to take on the bad debt and write off the losses, it could place strains on the credit position of the banking sector and likely the central government itself.

Transfer payments from the central government to local governments has increased to 70% of total expenditure according to China’s 2023 Economic Work Report and the central government’s own fiscal position deteriorated over the past decade.

There is also the obvious problem of moral hazard where consistently bailing out insolvent entities will continue to promote risky behaviour like taking on large debt burdens and investments which do not provide a sufficient return. It therefore makes sense that the central government has warned it will not step in this time. China’s Ministry of Finance has declared that there would be no bailouts by the central government for local governments with debt in distress, as reported by the State-run China Daily.

At the same time, not giving help to Guizhou’s government could have risked serious contagion effects for other local governments and the entire LGFV market. This bind is eerily like the situation of “too big to fail” banks in the West.

A likely scenario would be that the central government will at least need to let some defaults occur on LGFVs and off-balance sheet debt but provide direct assistance to local governments to ensure they at least make payment on their obligations for official debt.

The End of the Investment-led Growth Model?

Allowing defaults on LGFVs is likely to have negative consequences. It is the implicit backing from local governments that issue them that allow many LGFVs to obtain funding. LGFVs themselves tend to have opaque and complicated structures with high leverage and weak cash flows. With a government guarantee in doubt, even more LGFV defaults would be likely.

The central government has been encouraging the issue of bonds in recent years for local governments so infrastructure spending can again support the economy – but through so-called “special purpose bonds” instead of through LGFVs. These bonds are generally designed for a specific purpose, usually infrastructure spending. They do not count as part of the local government’s budget balance. Special purpose bonds honestly do not sound too different from LGFVs, only a re-wrapped package that is being sold as being less opaque.

Regardless of the name of the bonds, the main issue is that there continues to be investment in infrastructure with questionable revenue streams and financed with some form of local government debt. Special purpose bonds will have the same issue as LGFVs. But this has been a major part of China’s growth model over the past few decades. While this may have been functional and even ideal when China was growing rapidly and lacked basic infrastructure requirements, today, a lack of investments with sufficient returns is now manifesting into growing local government debt.

The Guizhou government potential rescue could be an important sign that the model of borrowing to spend on infrastructure to support the economy is increasingly becoming unviable, and that a downturn in investment in China may come sooner than previously thought. Kicking the can down the road may not be possible for much longer.

The central government could still try to pass on unperforming debt to other State-owned entities. Banks seem like the obvious choice. Otherwise, distressed asset managers (also State-owned) could attempt to mop up the bad debt once again.

Some combination of allowing less systemic defaults and indirect State-led rescues seems like the most likely scenario. It is after all, how the government has dealt with debt crises in the past. But now, it doesn’t have the rapid economic growth, which had been driven by investment, that will allow hiding the bad debt somewhere else.

The music may not have stopped playing yet, but this parcel of debt is getting heavy, and at some point, it might get too heavy to be passed around. Perhaps local government debt is that parcel that will have to land on the last one standing. The big question is who will be left holding the debt when the music stops? Only time will tell.

Sources:

5 topics