Demystifying the inter-relationship between interest rates and credit spreads

Many investors approach fixed income markets with a sense of trepidation as the concepts underlying then appear somewhat arcane. Partly this is due to the nature of fixed income investments and the more formalised dynamics and relationships which drive their returns.

To demystify the fixed income markets what follows is a series of primers outlining the key concepts behind fixed income dynamics and portfolio management. The fifth instalment of this series shall have a closer look at the relationship between interest rates and credit spreads.

Objectives of Central Banks

As noted in the primer on “What is credit spread duration?” there is a tendency towards a relatively high level of synchronisation between the market pricing of credit risk and the economic/financial cycle; there is also a high level of synchronisation between bond yields and the economic cycle. It therefore follows that there is a relationship between bond yields and credit spreads. The common factor driving this relationship between credit spreads and bond yields is the policy actions of central banks. To better understand such policy actions it is useful to consider that a central bank such as the Reserve Bank of Australia ('RBA') has the following objective :

“to conduct monetary policy to achieve its goals of price stability, full employment and the economic prosperity and welfare of the Australian people”.

Put another way one can view the objective of the RBA as being one of setting monetary policy to achieve the maximum level of economic growth compatible with its inflation target. Where the major policy tool available to the RBA, as with other central banks, is the official cash rate.

Monetary Policy Links Interest Rates and Credit Spreads

The interaction of the policy objectives of central banks such as the RBA creates a direct link between monetary policy and the economic cycle. The driver here is the trade-off between the rate of economic growth and inflation. Though there are many factors impacting economic growth and inflation it is useful to think of inflation as creating a speed limit to the rate at which an economy can grow. The existence of such a speed limit means that to maintain longer term economic prosperity central banks have a bias to manage monetary policy so that it “leans” against the cycle. Given such biases, over an economic cycle, increasing bond yields are associated with central banks raising official cash rates which is indicative of stronger expected economic conditions. Stronger economic conditions in turn positively impact on the fundamentals for corporations and credit spreads; i.e. credit spreads contract as bond yields rise. The opposite holds for declining bond yields which in turn are associated with central banks reducing official cash rates in response to deteriorating economic growth which is negative for credit spreads; i.e. credit spreads expand as bond yields decline. The result of this tendency for central banks to “lean” against the cycle is the generation a negative relationship between bond yields and credit spreads over a traditional economic cycle.

At this point it is useful to distinguish financial crises from traditional economic cycles. A financial crisis is where financial instruments and assets decrease significantly in value. Often such events are characterised by a material increase in investor risk aversion; i.e. materially lower demand for investors to assume risk. A characteristic of such financial crises is a rapid and material increase in credit spreads. Such financial crisis may have impacts on the economic cycle though that is not always the case. Indeed, it is the desire of central banks to prevent such financial crises from negatively impacting on economic growth which will drive their policy response to such events. Specifically, the reaction of central banks to financial crises has been the same as if there had been a major economic slowdown; i.e. reduce official cash rates materially so that investor appetite to assume risk is restored. The result is that there still tends to be a negative relationship between bond yields and credit spreads in response to financial crises though the dynamics between the two are somewhat different.

Implications of Portfolio Construction

The dynamics operating between credit spreads and bond yields have several implications for how these exposures are managed within fixed income portfolios.

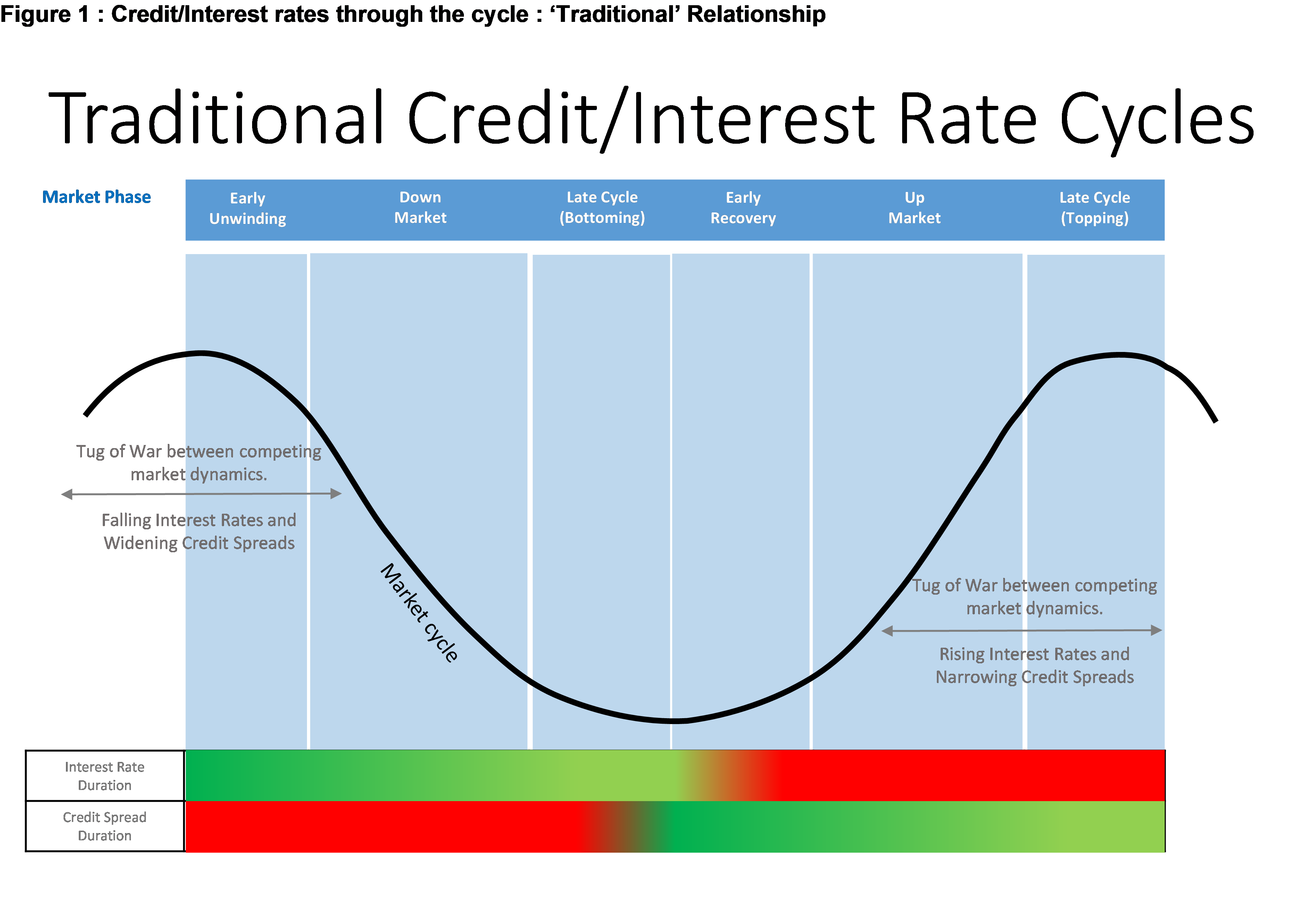

Firstly, there will be a tendency for active portfolios managers to proactively manage their DTS and duration exposures over the course of the economic cycle as in Figure 1.

Secondly, one of the core sources of return enhancement within active fixed income portfolios is the incorporation of a structural overweight to credit spreads. Such an overweight will tend to be more structural in nature as it provides investors with one of the more predictable premiums which can be earned in fixed income markets. This is especially true in markets such as Australia where the credit exposures tend to be relatively ‘high quality’; i.e. exhibit low default risk. A ‘high quality’ exposure to credit spreads means that the major risks faced by investors are the ‘mark to market’ impacts arising from movements in credit spreads. It is in this context that the traditional negative correlation between interest rates and credit spreads becomes a more important factor for investors as a means of reducing overall risk within a portfolio. Specifically, investors can utilise longer duration exposures to act as a risk offset to the higher level of credit spread exposure in their fixed income portfolio.

The longer-term negative relationship between interest rates and credit spreads provides useful tools by which to manage the overall risk of a portfolio. Specifically, by balancing these different exposures investors are in a stronger position to earn higher returns while still managing the overall level of ‘mark to market’ risk within their fixed income portfolio.

3 topics

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...

Expertise

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...