Dirigisme; our Australian Equities word of the year

It’s time for the word of the year. Oxford’s word of the year is ‘rizz’, and its erstwhile competitor Cambridge chose ‘hallucinate’, which we thought we were doing as markets resumed a 2021 rizz during November. Closer to home, the Macquarie Dictionary chose ‘cozzie livs’, a colloquial abbreviation of cost of living, reflecting the year of price rises, especially with interest rates. All worthy choices, to be sure. In an Australian equities context, the word of the year in our opinion is ‘dirigisme’; where the State plays an increasing role in economic activity and the control and allocation of private sector profit pools. When the federal government summons the providers of debt (major banks) and equity (superannuation funds) to discuss how ‘nation building’ can be undertaken in the energy transition, housing and defence sectors; it’s dirigisme.

We discussed in the September commentary how we see the state’s role in the energy transition as only increasing, and to an extent far greater than is currently imagined. Indeed, while the cost in Australia is impossible to dimension with precision, a few guideposts exist which suggests that the quantum involved will be far greater than currently anticipated. For reference, the Mining Supercycle almost 15 years ago saw investment of A$200b, for which significant productive capacity was added (including in iron ore, which today continues to produce enormous excess return for producers). As much of the investment attaching to decarbonisation will be substituting renewable energy for an existing, albeit socially toxic, energy source, it cannot be expected to produce anything like the same returns, and yet we expect the quantum required to be far larger.

It’s all in the formula

The guideposts to the investment required for Australia to decarbonise are several. At a crude level, an industry rule of thumb is that one watt of renewable energy costs US$1. The world’s biggest lithium-ion battery, built in South Australia in 2017 by Tesla, is reported to have cost in that vicinity, with 70MW of capacity contracted to the South Australian government, and a further 30MW of capacity and 90MWH of storage uncontracted, at a capital cost of A$90m. Another example rests in New Zealand, where with 1/5 of the population of Australia and a much lower land mass per capita, 82% of electricity generation is renewable today. ‘The Future is Electric – A Decarbonisation Roadmap for New Zealand’s Electricity Sector’ was produced by BCG in 2021 and commissioned by the major gentailers in that market. That extensive report detailed why New Zealand’s decarbonisation by 2030 to a system with 98% renewable energy will cost an estimated NZD$42b. The Clean Energy Council estimated last year that renewable energy in Australia is currently accounting for 36% of electricity generation, and it has a 2030 target of 82% renewable energy. Of course, in Australia the cost escalation from AU$2b to AU$20b attaching to Snowy 2.0 for 2,200 megawatts of generating capacity and approximately 350,000 megawatt hours of large scale storage is well known. Perhaps less well known in Australia is that this is not an isolated occurrence. In New Zealand, the proposed Lake Onslow pumped hydro scheme has seen its estimated cost quadruple to NZ$16b. Because of the cost inflation, the ultimate cost of decarbonisation in Australia is highly elastic, with a risk it could be materially higher than the A$300b which can currently be inferred from the industry rules of thumb and comparable projects. To put the A$300b (or multiples thereof) into context, the investment in NBN was circa A$50b (much of which has now been written off), highlighting the risk in dirigisme writ large.

Energy – now with added helium

The above matters for several reasons to an ASX investor. Firstly, the sheer quantum of this spend is such that it will be a tectonic shift in the economy, played out over many years. In itself, it will likely be inflationary. The energy transition will also be prone to missed deadlines and deferrals; already in the past two months, two planned, large withdrawals of fossil fuel energy capacity in the Australian market have been deferred (Loy Yang A in Victoria owned by AGL, where the Victorian government also agreed to provide capacity payments while AGL kept the plant operating in order to underwrite security of supply; and Eraring in NSW, owned by Origin). In each case, the deferral was in response to a request by the respective State governments reflecting concerns over system stability.

At a stock level, the energy transition played out through the failed A$19b takeover offer for Origin Energy (ASX: ORG) from Brookfield and EIG. Since the time the bid was announced in March, local wholesale electricity prices and futures have moved higher, the two major state governments have announced plans to defer plant closures and the 20% stake in Octopus Energy that Origin acquired three years ago (which has cost it A$700m) has also grown in value materially. Octopus has benefited from stellar growth in its global customer service platform, Kraken, which now has 30m customer accounts globally. It has equally created a large energy retailing business, with the imminent acquisition of Shell’s UK and German home retail energy business following last year’s acquisitions of Bulb Energy (1.5m customers) and Avro Energy (0.6m customers). This has seen Octopus become Britain’s second largest energy retailer with 6.5m customers. Given Octopus only commenced operations in 2016, and continues to have global growth aspirations in energy retailing, its valuation is obviously elastic yet highly material.

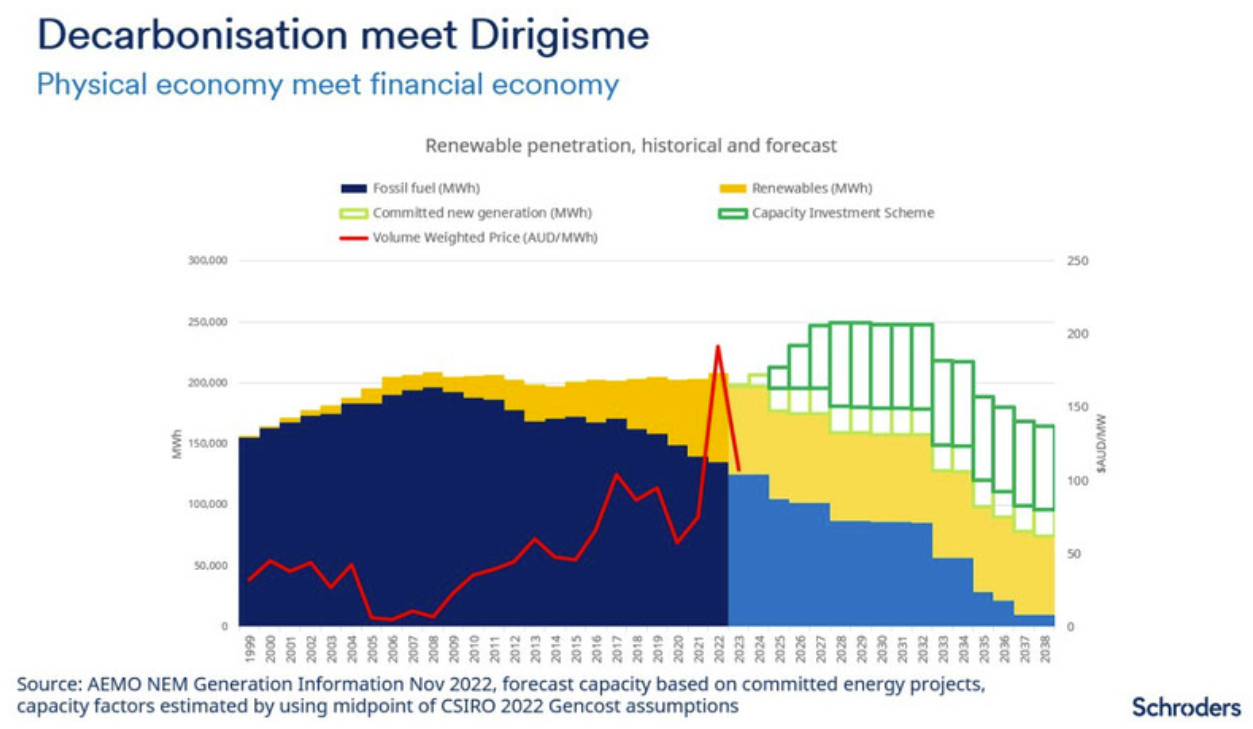

To assist in facilitating the required investment for the decarbonisation of energy supply in Australia, the government announced the capacity investment scheme (CIS) during the month. This is an ambitious program; as can be seen in the chart above, the volume of new energy generation looking to be spawned by the CIS is multiples of existing new committed generation in Australia. The CIS underwrites returns to project developers for generation and storage, however it carries with it a ceiling price as well as a floor price; and hence while returns are protected during the day when electricity prices routinely move into negative territory, night time spikes in prices won’t see windfall gains accrue to government underwritten projects. This arrangement mimics existing global schemes; where, for example recently in the UK, no bidders were enticed into an auction for the provision of offshore wind due to price floors being set at too low a level. Meanwhile, the equally required investment in transmission remains unaddressed; which is one reason why Origin’s remaining fleet of gas peaking plants may prove strategically increasingly valuable.

Bond sensitives and growth stocks – shaken and stirred

The other remarkable feature of the market’s returns during November was the rally in bonds globally, taking Australia with it, with a month end yield of 4.4% after a rally of 52bps through the month. On cue, the bond sensitives and growth gorillas on the ASX came out of an extended hibernation; and the impact on underperformers was just as pronounced, with commodity and energy stocks melting down. REITs have proven most sensitive to bond yield movements, and the most leveraged REIT – Charter Hall Group (ASX: CHC) (+20%) – did best. The growth stock cadre also responded to the bond bid, with Block (ASX: SQ2) (+58%), James Hardie (ASX: JHX) (+25%) and healthcare names all very strong. Healthcare on the ASX has been somewhat anachronistic – ASX healthcare stocks have sold off through the year far more than the sector has globally, and the rally through November was far more pronounced than was seen for the sector globally as well. The sector in Australia has assumed an undue reliance upon sentiment attaching to the ultimate penetration of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) drugs, with Resmed (ASX: RMD) at the vanguard but CSL (ASX: CSL) also being affected as GLP-1 sentiment waxes and wanes. The portfolio’s underweight position in CSL and overweight position in Ramsay (ASX: RHC) detracted from performance through November. While activity is weakening in a global sense, the local economy remains strong, with jobs and wages data, and house prices, all thus far largely unaffected by the 13 rate increases imposed by the RBA through the past 18 months. Indeed, the new RBA Governor warned during the month that while it has only taken nine months for inflation to drop from 8% to 5.5%, it will take another two years in the RBA’s estimation for it to drop the same amount again to get within the target range of 2%-3%. If the RBA is right, the bond rally – and attendant extreme reaction in interest rate sensitive and growth names we saw on the ASX through November – may yet prove ephemeral.

The month also saw returns hurt by holdings in the commodity and energy names that generally underperformed aggressively as the market rotation went into full swing. Amid the energy names, overweights in Santos (ASX: STO) and Origin (ASX: ORG) hurt performance as the oil price fell through the month to the lowest levels seen since mid-year. Our positions in South32 (ASX: S32) and Alumina (ASX: AWC) also detracted from performance given ongoing weakness in the Alumina price, albeit this weakness was mild relative to that for the oil price, which in itself was a modest decline relative to the 30% decline in Spodumene prices during the month, seeing performance benefit from not holding Liontown (ASX: LTR), Pilbara Minerals (ASX: PLS) and Allkem (ASX: AKE). Ironically, some of the better portfolio performers through the month also came from the materials sector, albeit the housing related part (in the form of Hardies and Boral).

13 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned