Do government bonds still have a role in investor portfolios?

.png)

The concept of diversified portfolios was first popularised by Harry Markowitz’s 1952 “Modern Portfolio Theory”, which outlined the basic tenets of how risk-adjusted returns could be maximised through carefully constructing a portfolio on the basis of risk, returns, and correlations between the underlying securities.

Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, then came along and simplified the concept through the 60/40 portfolio rule - where investors could maximise risk-adjusted returns through creating a portfolio with 60% exposure to equities, and 40% exposure to bonds.

Through having such a balance, investors could meet investment goals, whilst simultaneously achieving adequate diversification to generate optimal risk adjusted returns.

However, as interest rates have continued to move lower over recent years - a product of a two-decade-long period of disinflation, and the COVID-19 pandemic, the question continues to be asked - do government bonds still have a place in portfolios?

In today’s note, we will take a look at government bonds, from the perspective of our 5-step investment decision-making process:

- Fundamentals

- Technical

- Sentiment

- Correlation

- Catalyst

Fundamentals

From a fundamental perspective, government bonds score relatively poorly.

Interest rates are near all-time lows, with US 10-year treasury yields trading at 1.32%, and Australian 10-year treasury yields trading at 1.25% as at the close of business on Monday the 20th of September.

Source: Bloomberg

More importantly, real rates (adjusted against inflation linked government bond yields) closed at -0.99% and -0.79% respectively.

This paints an ugly picture, where investors aren’t even able to achieve a positive rate of return, after adjusting for the impact of inflation.

Whilst default risks are very low, with yields/income relatively assured, the only way for investors to earn a positive real return right now, would be if rates were to go even lower (leading to capital price appreciation), or if inflationary expectations took a dive below ~1.30% p.a. (i.e. inflation below the nominal yield of the bond).

The COVID-19 pandemic and the unprecedented levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus can in part be blamed for this record low-interest rate setting - as central banks have thrown the “kitchen sink” to prop up the economy in lieu of rapidly declining economic activity.

However, zooming out we can also see that interest rates have been on a downward trajectory for the past 20 years, as developed markets grapple with a disinflationary economic environment, a product of the three D’s:

- Debt

- Demographics

- Declining costs of technology

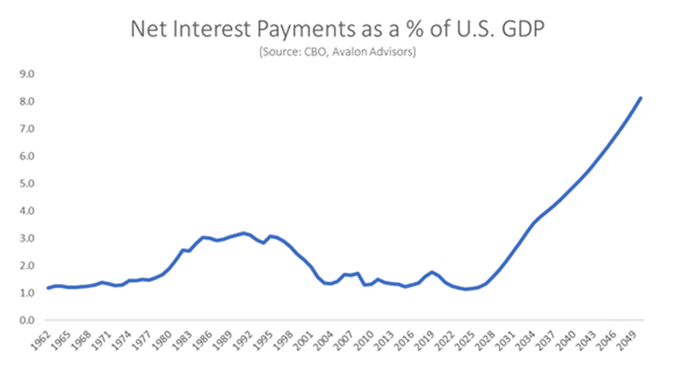

As government debt as a proportion of GDP has reached record high levels, it has continued to create a misallocation of resources, both in the present and the future.

Instead of capital being allocated purely to those with the greatest utility, it has been distributed to the government, who don’t allocate on the basis of profit maximisation, and supply and demand, but instead by the mandates and policies instituted by that government.

Governments will also have to service these growing debts into the future, placing a burden on future budgets and restricting the amount of money available to invest into future government expenditure (therefore constraining economic growth and inflation).

Our ageing demographic profiles have also taken a toll on our economies, where public sector burdens have increased, and proportions of working-age populations have decreased.

Given the fact that almost all central banks have an inflation-targeting mandate, these disinflationary forces have necessitated a prolonged period of historically low-interest rates, as they use all means necessary to meet their inflation targets.

These deflationary forces are unlikely to abate, and will likely even become stronger, subsequently ensuring a low-interest rate setting for the foreseeable future.

Therefore - it is unlikely that we will see government bonds yields move significantly higher in the coming years - irrespective of how quickly the economy is able to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, whilst this means that current investors will likely continue to earn negative/zero real rates of return, a significant move higher is unlikely and will ensure that potential losses are also restricted.

Technical

US Treasury yields have fluctuated significantly over the past 18 months, reaching lows of 0.508% in August 2020, before rebounding up to 1.742% in March 2021.

We will only look at US Treasuries in this example, however, the same narrative has played across almost all developed market economies.

The reasons behind these fluctuations have largely been driven by two factors:

- Inflationary expectations

- Federal Reserve intervention

These two factors should continue to drive interest rate trajectories for next 2-3 years, where relative movements will be determined by whether inflation is in fact transitory, and tapering/rate hike timelines.

In the event that inflation is in fact transitory - a fact becoming increasingly more likely with each CPI release, we only need to look so far as to the timeline on which the Federal Reserve, and other central banks have in regards to asset purchase tapering/rate hikes.

This timeline will likely see interest rates remain very low for the coming years, with rate hikes coming in 2023/2024.

Sentiment

From a sentiment perspective, government bond markets are mixed.

Should we see no material increases in inflation, yields will likely remain near current levels given central banks will be able to maintain their ultra-low interest rate settings required to promote economic recovery.

This would protect current investors from any significant capital losses from higher yields.

However, should we see inflation rise faster than expected, transgressing beyond the “transitory” narrative imposed by the Federal Reserve, bond yields would move higher, having a myriad of effects on markets.

If you’d read our note “Inflation is Psychological” on 12 August, we spoke about the potential dangers of an inflationary spiral, which would see bond yields move even higher, and over a longer period as consumers reinforce inflationary impulses through their consumption activities.

Correlation

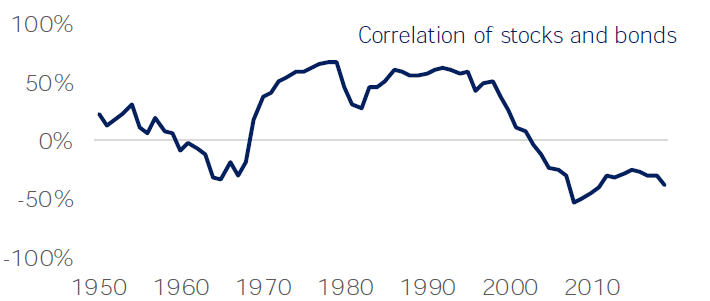

Correlation is one of the most important factors which drives investment into government bonds, given the majority of investment thesis are centered around its volatility-reducing capabilities.

In the current market environment, correlations are likely to be affected by inflation and/or economic recovery timelines.

In inflationary environments, stocks and bonds are affected similarly, therefore creating a positive correlation (as inflation erodes cash flows of both stocks and bonds).

However, in an environment of declining economic activity, stocks and bonds are negatively correlated (as stocks are negatively impacted, and bonds positively affected through resulting reductions in central bank interest rates).

When optimising portfolios, the greater the negative correlation between stocks and bonds, the lower the required return for each asset (given declines in one will be offset by increases in the other).

Over the past two decades, we have seen negative correlations between stocks and bonds, supporting investments into government bonds.

Source: State Street Global Markets

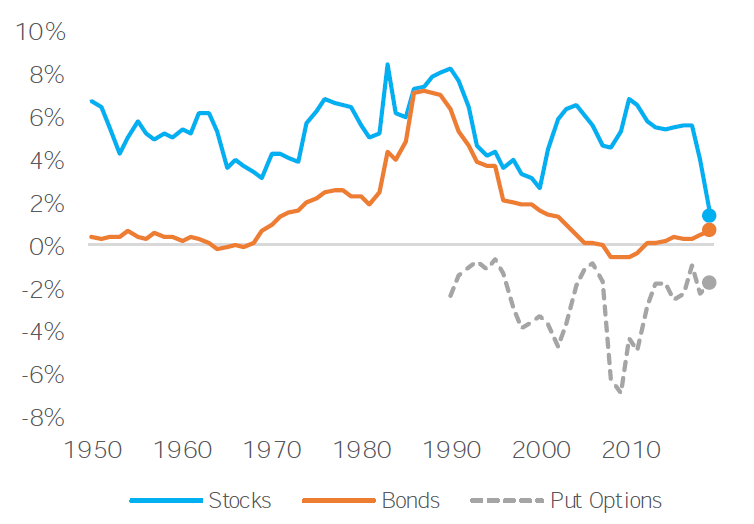

Therefore, regardless of the negative rates of return on offer, investments in government bonds will still enhance risk adjusted returns, given there are no other risk-free alternatives.

Hold cash, and you will see its value deteriorate at a greater level (given inflation) and hold only stocks and you will see a reduction in risk adjusted returns.

Alternatives to hedge out stock volatility like put options will also incur a greater premium, leaving government bonds as the lesser of the two evils.

CAPM-implied expected return premiums vs the market price of a put option protection

Source: State Street Global Markets

Therefore, the only environment where investments into governments bonds are sub-optimal, would be if inflation were to move significantly higher, in tandem with higher economic growth – an unlikely circumstance.

Investors who are seeking to enjoy these correlative benefits, whilst increasing absolute returns, could also invest into credit.

This investment would be most suited to investment-grade bonds, which have a lower relative beta to equity markets than their high yield counterparts.

Such holdings can take the form of direct bond holdings, or through credit funds – which offer more diversified exposures, as well as capital market access unavailable to retail investors, and most wholesale investors.

Catalyst

All investment decisions should be justified by a suitable catalyst.

Given US treasuries, and other major government bond markets are some of the most liquid in the world, they are extremely efficient and largely price in any changes which would affect valuations.

As a result, investments would usually have to be made in advance of the catalyst occurring.

Catalysts which could impact upon government bond markets in the coming months/years would be changes in inflationary outlooks, slower than expected economic recovery, and a 3rd/4th wave of COVID-19 cases.

Government Bonds Are Still A Useful Diversifier

When looking at government bonds at the security level, the picture isn’t all that pretty.

Real rates of return are negative and near all-time lows, with little prospect of moving lower (creating capital appreciation for existing holders) or moving higher (creating a more attractive yield for future investors).

However, when looking at the picture from a correlation perspective, the investment thesis for government bonds in the context of diversified, utility maximising portfolios is still sound.

Negative correlations between stocks and bonds necessitates less returns from both asset classes, and as such, the negative real rates of return offered by government bonds are still able to maximise risk adjusted returns on the portfolio level.

Investors wishing to increase absolute returns whilst still gaining the correlative benefits of bonds can instead look to investment grade credit, where returns are enhanced by the addition of the underlying credit risk of the issuer.

Investment-grade issuers, like our 4 major banks, are highly unlikely to ever default (given the implicit government guarantees in place) and thus can play a meaningful role in developing diversified portfolios.

4 topics

.png)

Mike is an Investment Analyst at Mason Stevens, where he is responsible for a broad range of investment management activities, primarily focused on the firm’s fixed income product offering and wealth services. Mike has a strong interest and...

Expertise

.png)

Mike is an Investment Analyst at Mason Stevens, where he is responsible for a broad range of investment management activities, primarily focused on the firm’s fixed income product offering and wealth services. Mike has a strong interest and...

.png)