Don't spoil your festive season with market forecasts

As the calendar flips over to December, attention naturally shifts to the year ahead. What’s in store for 2022? You will read plenty of answers to this question, but before you do anything about it consider this.

It is the silly season after all. As you work your way through Christmas parties, presents, and an overdue vacation, you will likely also find yourself with an inbox full of economic and market forecasts from various financial commentators. In them you will find confident predictions for what lies in store for equity markets in 2022, based on the forecaster’s outlook for inflation, monetary policy, elections, supply chain, COVID-19 and so on. Let’s see what history tells us about how the accuracy of such market outlooks.

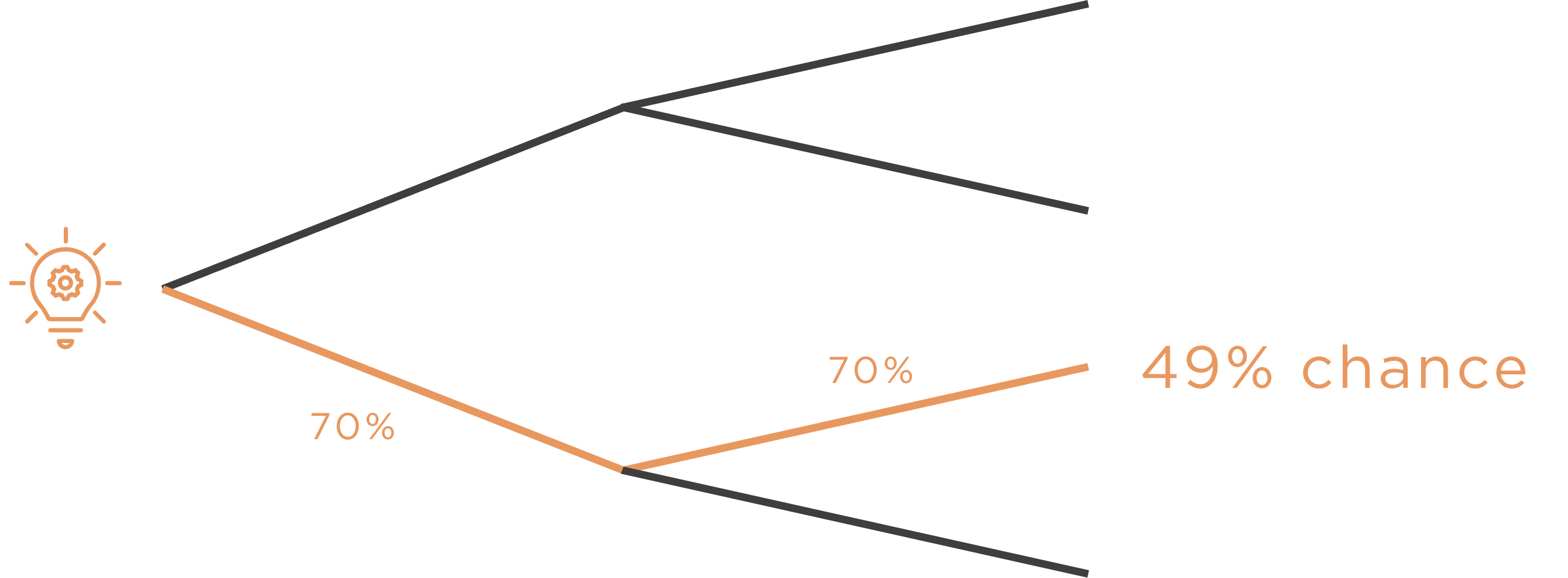

Market forecasts are usually derived from multi-part assumptions, meaning a forecaster assumes A will happen, because of which B will then happen. For example: “central banks will tighten monetary policy in 2022, as a result of which equity markets will decline.” With multi-part assumptions, the likelihood of being correct is calculated by multiplying together the odds of each proposition. If a forecaster has a 70% chance of being right with their outlook for tighter monetary policy, and the chance that the equity market declines because of tighter monetary policy is 70%, then the probability that the forecast proves correct is 70% times 70% which equals 49%. These are worse odds than tossing a coin, which should be pause for thought. The more assumptions embedded in the proposition, the less likely it is to prove correct.

Market timing involves such complex, multi-part assumptions, which is why the odds of success are low. CXO Advisory Group tracked US equity market forecasts from 68 strategists who publish their outlooks publicly, referred to by CXO as ‘market gurus’. Over the period 1998 to 2012 these gurus made 6,582 forecasts with an average accuracy rate of 48%, meaning they were correct less than half the time. The results were studied by Wim Artoons in a 2016 article ‘Market Timing: Opportunities and Risk’. Artoons concluded that

‘after transaction costs, no single market timer was able to make money’.

Aswath Damodaran, who today is Professor of Finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business, has studied market timing strategies. He looked at asset allocation mutual funds in the US, so called because, rather than being 100% equities they can time the market by moving between stocks and bonds and cash. As such, they should do better than the equity market.

Over the 10 years to 1998 these market timing funds on average underperformed the S&P 500 by 5.0% p.a.

So much for timing the market. What about identifying growth thematics? Could 2022 be the year of biotech, robotics, AI? Perhaps it’s the year that EVs go mass market. Once again, the data is not encouraging.

Thematic funds on average underperformed the broader equity market by 3.0% p.a. over the period 2000 to 2019 (Swiss Finance Institute).

As humans, we are naturally impressed by complex approaches. It’s intuitive to believe that outperforming the market requires the sophisticated, multi-part reasoning we hear from those expressing market timing and thematic investment views. The facts tell a different story.

It’s also human nature to be drawn to crystal balls. Being told the future takes away the anxiety which comes with uncertainty. However, the future is unknowable, and we have to make peace with that. In equity investing, living with uncertainty is much easier when we realise that much of what most participants and commentators fret about, such as election outcomes and monetary policy, has very little bearing on long-term outcomes.

As an alternative to anticipating the next year in financial markets and positioning yourself accordingly, I offer the following:

- Focus on the main game, which is long-term investment outcomes. To do this, let go of the need to maximise short-term results. Trying to be on the right side of all the inevitable zigs and zags in the market along the way is more likely to detract from than enhance long-term returns.

- Recognise uncertainty through owning only all-weather businesses. If inflation is a risk, which it always is, avoid businesses which suffer lasting damage through inflation.

- Own winning businesses, those that not only outgrow their peers in normal times but positively thrive competitively in difficult conditions.

If you’d like to know more visit our website.

1 topic