Dot-com zombie parallel universe

“If you bought every company that lost money in 2019 … you’ll be up 65 percent so far this year.”

- Joel Greenblatt, Masters in Business interview October 2020

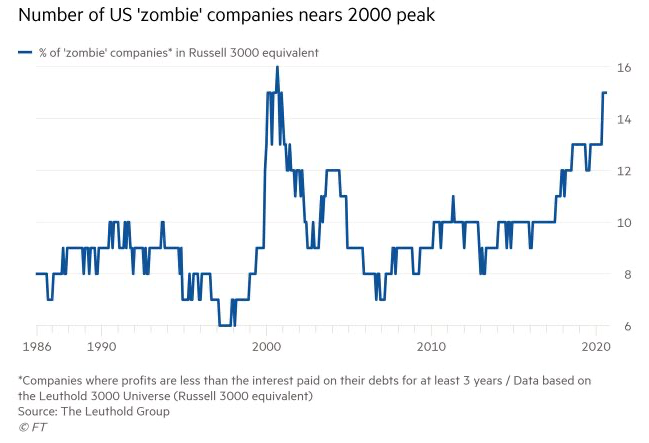

Who would have thought buying loss making companies was the quickest way to make money over the last few months? The last time zombie companies were valued at extreme levels was during the Dot-com boom 20 years ago. Currently, about 15% of listed US companies are classified as zombies and is fast approaching the Dot-com peak.

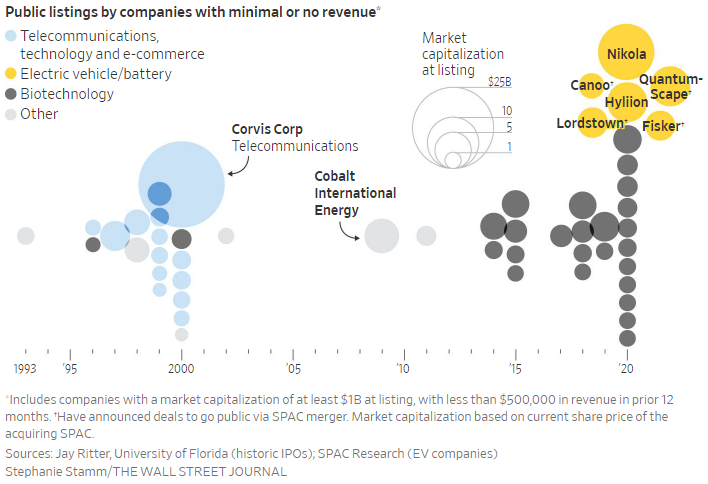

Typically, companies with unproven business models are funded by venture capital investors. However, the stock market’s speculative frenzy of looking for the next Zoom or Tesla has made money virtually free for capital hungry start-ups. Hence, in the current environment many companies with unproven business models are attempting to bypass the venture capital stage and seek capital from the stock market via a public listing. The interest in companies listing with minimal or no revenues is more fever-pitched than it was 20 years ago.

An example of the speculative fever is the electric car manufacturer called Fisker. The company currently has no revenues and plans to have its first electric vehicle produced in 2022. What excites speculators is the US$13 billion revenue forecast by 2025, never mind the fact that it took Tesla nearly a decade to surpass that revenue. Another much-publicised company is Snowflake, a loss-making data warehousing company. Its initial public offering broke records – it was the largest company to ever double in value on its opening day, reaching a market capitalisation of about US$75 billion.

High quality companies can also get caught in the froth

Investing in zombie companies may be considered speculation. Alternatively, investing in companies with a long track record of earnings growth is often considered the best way to navigate a low growth, uncertain world. Or is it?

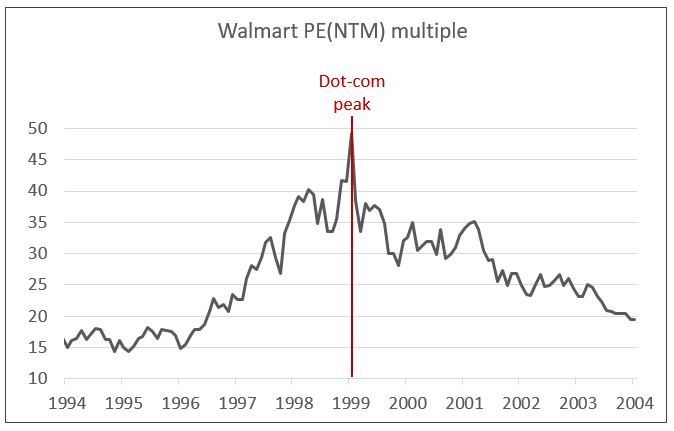

Over the long-term share prices track earnings. However, there are times when valuations can substantially disconnect from underlying fundamentals. This is best exemplified by Walmart, where a high quality, robust company was caught up in speculative fever during the Dot-com mania. The following chart highlights Walmart’s Price/Earnings (PE) multiple for the period between 1994 and 2004.

Source: Refinitiv, Vertium

Since its IPO in the 1970s, Walmart has delivered consistent earnings growth spanning multiple decades. For example, in the five-year period pre-and post the Dot-com peak, its earnings per share (next twelve months) growth was about 15% p.a. and 14% p.a. respectively. During that time, Walmart's share price severely disconnected from fundamentals when it skyrocketed along with the Dot-com high flyers. When the bubble popped, its future earnings growth continued to be robust but was not strong enough to offset the unwinding of its extreme PE multiple. Walmart was so overvalued (peak PE multiple of 49x) that it subsequently delivered a decade of zero returns.

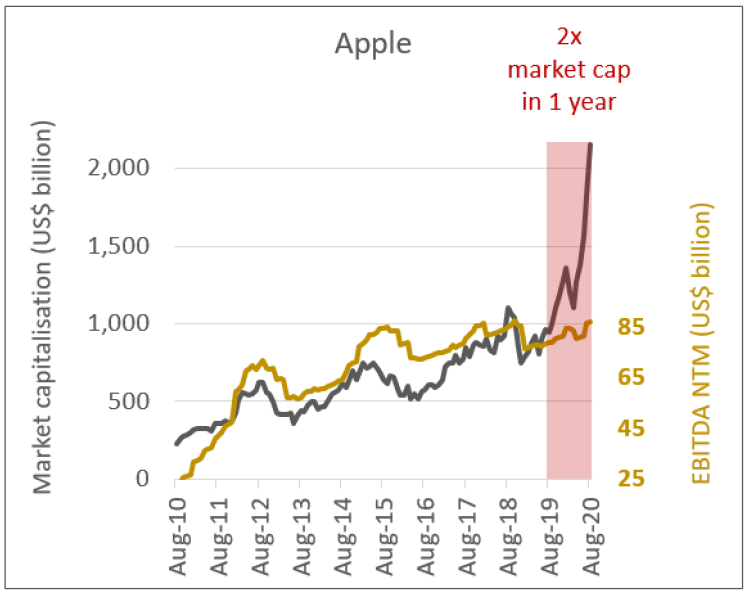

The recent surge in valuation of some US mega companies makes the Walmart bubble look tame. During the Dot-com mania, Walmart’s share price increased 59% during the 12-months prior to its peak in December 1999. In comparison, Apple’s share price has more than doubled for the 12 months to August 2020. The disconnect is more apparent when its market capitalisation is compared to its EBITDA (next twelve months) history. Over the last five years Apple’s EBITDA has hardly grown, just 0.6% per annum, a clear sign that the company is maturing.

Source: FactSet, Vertium

It took Apple about 40 years following its IPO to be valued at US$1 trillion. It took only one more year to add another US$1 trillion to its valuation. Apple is currently the world’s most valuable company by market capitalisation.

Australian experience

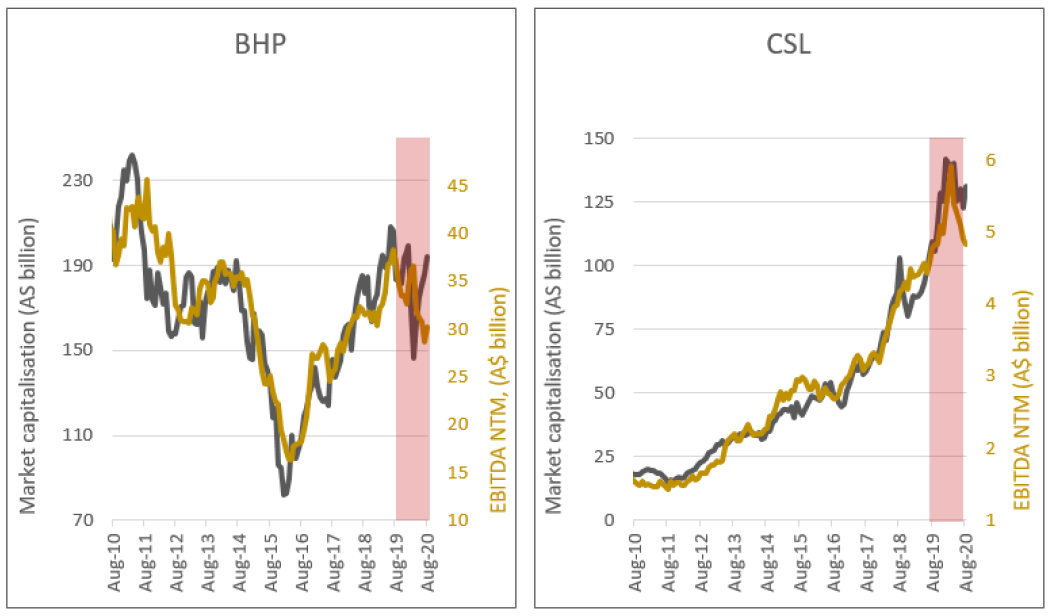

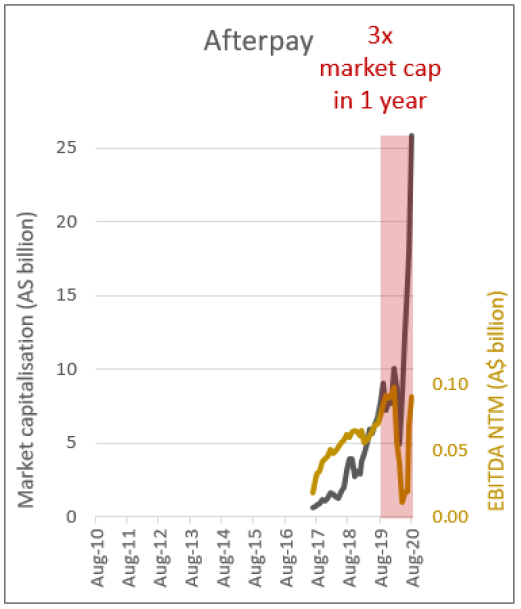

Fortunately, in Australia the disconnect between valuations and fundamentals are not as prevalent as the US stock market. For example, BHP and CSL’s share prices have largely followed earnings estimates over the last 10 years, including the last 12 months, when market euphoria has been rife in many parts of the stock market.

Source: FactSet, Vertium

The pockets of speculation in the Australian market include the buy now, pay later sector led by Afterpay (APT). Over the last 12 months, APT’s market capitalisation has tripled despite its EBITDA estimate being at similar levels to a year ago. Of course, the COVID surge in discretionary retail has helped its business. But its current market capitalisation is implying that the expectation of future profits is three times greater than a year ago. From its IPO in 2017, APT has surged to become the 15th largest stock by market capitalisation listed on the ASX.

Source: FactSet, Vertium

History lesson

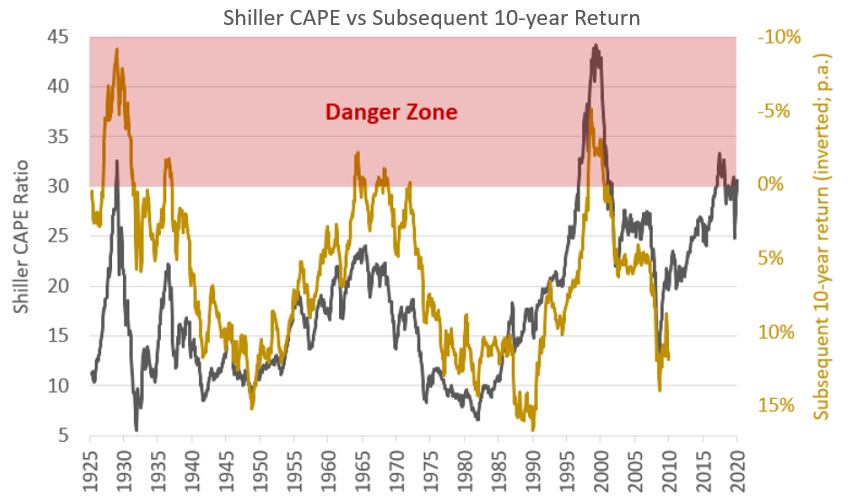

There have been a few speculative manias over the last century, which all ended badly. The chart below plots the Shiller CAPE ratio (PE ratio over the last 10 years of earnings adjusted for inflation) and the subsequent 10-year returns for the S&P500 (inverted).

Source: http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm, Vertium

The Shiller CAPE ratio does not help in guiding short to medium term returns. However, it provides a good barometer for long term returns. When valuations are extremely high the subsequent 10-year returns are low and vice versa. For example, the 1920s (roaring 20s), mid-60s (nifty fifty) and late 90s (Dot-com boom) were followed by negative 10-year returns. While the current Shiller CAPE multiple is not as extreme as the Dot-com bubble it is high enough to highlight potentially poor future returns.

Welcome to the parallel universe

The Dot-com boom and current plethora of zombie companies have stark parallels. Both have several profitless companies at record levels. Both have surging valuations disconnected from their fundamentals. And both weren’t just limited to speculative stocks, with Walmart in 2000 and Apple currently swept up in the mania.

This time could be different. Global Central Banks are pouring liquidity into the financial system to fend off a COVID recession. Further, some zombie companies may eventually become profitable over time when they reach scale like the tech juggernaut, Amazon.

However, the one thing that is not different in manias are extreme expectations. Irrespective of whether a company is loss making or is highly profitable when high expectations disappoint volatile returns always ensue. During periods of speculative excesses, a capital preservation mindset is required to survive and possibly thrive amongst the walking dead.

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

2 topics

3 stocks mentioned