How to destroy a competitive moat

Too many companies are milking, not nurturing, their competitive advantage. That might help this year’s profits, but the long term impact can be damaging.

“Well, the first thing we have to do, I suppose, is listen,” Paine said when asked how his team might reconnect with Australia. “We’ve potentially maybe had our head in the sand a little bit over the last 12 months, if we continue to win we can kind of act and behave how we like and the Australian public will be okay with that.”— Daniel Brettig, Cricinfo, quoting Australian cricket captain Tim Paine

Tim Paine only made one mistake: the timeframe. Australian cricketers’ on-field behaviour has been an embarrassment to the country for more than a decade. The resentment among fans has been building for a long time—apparently unnoticed by the players themselves. When Steve Smith, Cameron Bancroft and David Warner admitted to premeditated cheating in a recent Cape Town test match, it erupted like Mount Pinatubo.

The corporate world should read Paine’s words carefully. As the gap has grown between a CEO’s pay and their typical customer’s, so has the gap between management’s impression of their business and the actual customer experience. Not only are they providing fodder for the tabloids, they are risking billions of dollars of shareholder value.

Most recently, most egregiously, Facebook has been found to be wantonly abusing its members’ trust. I almost said “clients” trust. But it has become patently obvious that Facebook members are the company’s product and the advertisers are its clients.

The Cambridge Analytica debacle

In 2015, in the lead-up to the US presidential election, UK company Cambridge Analytica ran a Facebook survey that gave them access to data on 270,000 Facebook users. Presumably most of them knew they were giving their data away. But they apparently didn’t know that Facebook was also giving access to data on their friends as well. Cambridge Analytica ended up with data on 70 million Facebook users—some of whom had gone through the tortuous task of ticking boxes to try and stop Facebook selling their data—and used it to craft very specific advertising around the 2016 US presidential election.

Facebook’s users rightfully feel violated. I have deleted my account (not something they make easy) and a recent survey suggests 19% of Americans are planning on doing the same. They probably won’t —founder Mark Zuckerberg recently told the media the impact so far was “not material”. But the brand damage has been meaningful.

This is more than a story about a large corporate stuffing up. It has important investment implications, and provides a wealth of insight into the concept of competitive advantage. Often viewed as something permanent, in reality competitive advantage can be ephemeral. And management can do a lot to destroy it.

Investors view competitive advantage as a good thing. Economists view it as the opposite. Think of it as any advantage that a business has that allows it to earn above average returns on capital—what the economists term economic rent. In an efficient, competitive world when one company is earning above average returns on capital, competitors invest in the sector and returns come down in the form of lower prices.

Competitive advantage is simply one or more of a number of structural factors—Warren Buffett calls them moats—that stop the competition from arriving and allow a company to sustainably charge higher prices than it needs to.

What’s wrong with sustainable moats?

There’s no doubt it is a good thing as an investor. High returns on capital allow companies to grow for long periods of time and mean shareholders can benefit as a result. The problem is that it is very rarely permanent. Maintaining competitive advantage requires constant investment. Too many stewards —Facebook being a prime example—see it as something to be milked rather than nurtured and grown.

At the time the Facebook scandal erupted, Gareth and I were in Paris meeting with Société BIC (listed in Paris), manufacturer of the eponymous pens, razors and lighters. With less people smoking and writing, they are facing a crisis of their own. But it is the razors side of the business which got us thinking about competitive advantage. More specifically, the many ways in which you can erode it.

BIC’s main competitor and the industry leader is Gillette (owned by NYSE-listed Procter and Gamble). Its business model—sell the razor for little profit but charge a premium for the razor blades— is now a case study in every business school and has been replicated many times. The company itself fell in love with the concept.

Prices at my local supermarket hit $20 for a pack of four razor blades. I’m relatively price insensitive, but $5 a razor blade was an affront. So I did something I never would have done had they been $2 each—I looked for an alternative (hence the beard).

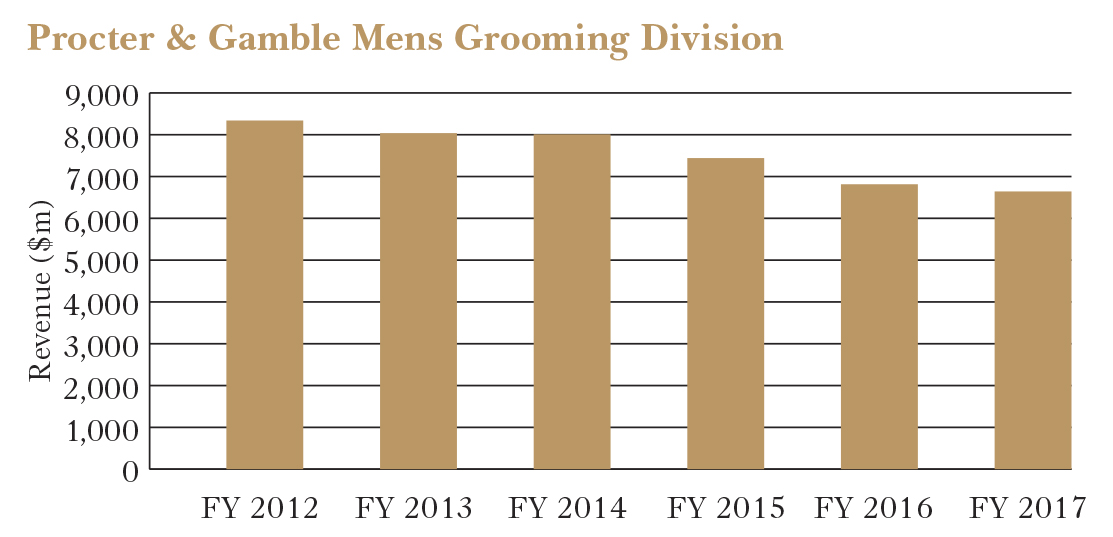

So have plenty of other formerly loyal customers. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, Gillette’s market share fell from 70% in 2010 to 54% in 2016. Most of the competition is coming from online upstarts like Dollar Shave Club, who offer the same product for a fraction of the cost. Gillette has recently slashed its prices by 20% and is running a bizarre advertising campaign almost apologising to customers for the previously sky-high prices. It’s the perfect example of how to destroy a competitive advantage by pushing pricing power too far.

Most moats are not uncrossable, rather it’s not worth spending the money necessary to cross it. If you build a large enough pot of gold on your island, though, the competition will throw enough resources at it to bridge the moat. BIC, which was happily riding Gillette’s coattails on the way up, is now unhappily caught in the downdraft.

Mistreating stranded customers

The second, more common mistake is to mistreat your clientele because they can’t get off your island. When the moat dries up, narrows or changes, the managers running these businesses are surprised when their customers run for the exits.

The taxi industry has been guilty of this in Australia. For decades we have suffered from dirty taxis, poor service and high prices. Along comes Uber with, for all of Kalanick’s faults, a service that is easy to use, cheaper and generally cleaner. The taxi industry is astonished that we don’t feel much sympathy for them.

The banking sector is also guilty. Most senior executives still think their problem is one of perception rather than reality. The cross selling and associated conflicts of interest have done a lot of damage to their brands, and they are businesses where the brands were worth a lot.

Which brings us back to Facebook. Founder Mark Zuckerberg’s tardy and inadequate response to the Cambridge Analytica debacle shows he is still in “it’s just a minor issue” mode. A 2016 memo subsequently surfaced, written by early Facebook employee Andrew Bosworth, justifying the company’s aggressive policies as a means to an end:

“The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is *de facto* good…That isn’t something we are doing for ourselves. Or for our stock price (ha!). It is literally just what we do. We connect people. Period.” Mr. Bosworth, known as Boz, said this justified “questionable contact importing practices” where users give up their friends’ data, and implied the privacy policy language was meant to deceive with “the subtle language that helps people stay searchable by friends”. –Facebook memo outlines ‘ugly truth’ behind its mission, Financial Times

Facebook is doing its best to erode what is an incredibly strong competitive advantage. They desperately need their Tim Paine moment.

This is an extract from recent quarterly report. Other topics include some new portfolio additions and an analysis of an investment gone bad.

3 topics

.jpg)

.jpg)