Factor investing and industry concentration

Should factor-based portfolios be industry neutral?

The last three decades have seen the evolution of factor-based investing, whereby portfolios are formed to give investors exposure to one or more factors that are associated with high returns. For example, stocks with high book-to-market ratios expose investors to the value factor, small stocks expose investors to the size factor and high yield stocks expose investors to the yield factor.

There is debate over whether a factor-based portfolio should be industry neutral. Suppose the investor’s strategy is to buy stocks that meet a certain set of value and quality criteria, like low prices relative to earnings or cash flows, high quality of accounting information (cash earnings are close to reported earnings and low earnings surprise) and low asset growth. Should you buy stocks that rank highly on these value and quality metrics across all stocks in the investment universe, or should you buy stocks that rank highly from within their industry sectors? The first approach is likely to help in picking industries that are cheap because the market has been overly pessimistic towards their prospects. But the problem is that the portfolio will perennially be underweight growth industries.

Researchers addressed this question by forming value-based portfolios of U.S.-listed stocks over 57 years from 1963-2020, considering market capitalisation, book-to-market ratio, return on equity, asset growth and momentum.[i] They found that, on average over six decades, long-only value-based portfolios had a better return for risk trade-off when stocks were ranked without consideration of industry (which overweights value industries like utilities and finance and underweights growth industries like technology and healthcare), compared to picking the best value stocks from within each industry (the industry neutral approach).

The problem for investors is that ignoring industry when ranking stocks on quantitative characteristics can lead to an untenably long period of underperformance. Over the 27-year history of the MSCI All Country World Value and Growth indices (December 1996 to May 2024), the 10-year annual differential between value and growth returns ranges from 5.5 per cent in favor of value (ending February 2010) to 6.4 per cent in favor of growth (ending August 2020). In aggregate the value index earned annual returns of 7.3 per cent, compared to 8.2 per cent for its growth counterpart, representing a growth premium of 0.9 per cent.

Australian high yield portfolios

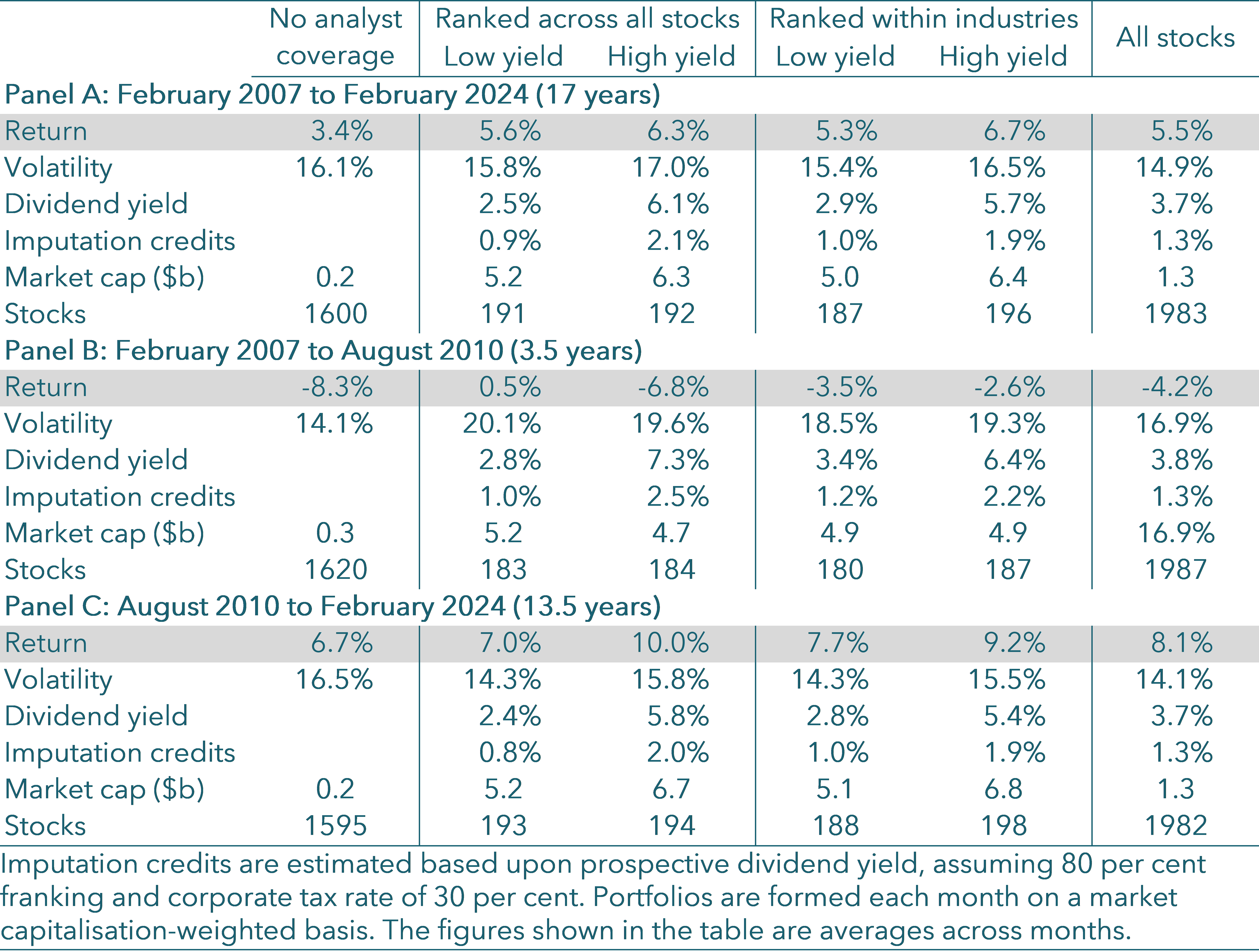

Consider one specific stock characteristic associated with high returns on Australian-listed stocks: dividend yield. Each month over 17 years ending in February 2024 I computed 12 month forward dividend yields on Australian-listed stocks from analyst forecasts and formed market capitalisation-weighted portfolios. On average there were 1983 stocks in the sample of which 383 had analyst forecasts. Stocks with analyst coverage comprised 85 per cent of market capitalisation. The risk and return profile of high versus low yield portfolios is shown in Table 1, for stocks ranked without consideration of industry, and for stocks ranked within industries according to the Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) of FTSE. When portfolios are formed without consideration of industry, the yield on the low dividend yield portfolio is 2.5 per cent versus 6.1 per cent for the high dividend yield portfolio. The corresponding dividend yields when portfolios are formed on an industry neutral basis are 2.9 per cent and 5.7 per cent. For the whole market the dividend yield is 3.7 per cent.

The table shows that, over the entire sample period, high yield stocks earned a pre-tax return premium over low yield stocks of 1.4 per cent when portfolios were formed on an industry neutral basis and 0.7 per cent when portfolios were formed without consideration of industry. Ignoring industry in portfolio formation brings comparatively higher incremental tax benefits from dividend imputation because there is more disparity in yields between the high and low yield portfolios. Assuming 80 per cent franking and corporate tax rate of 30 per cent, imputation credits are 2.1 per cent and 0.9 per cent, respectively, for the high and low yield portfolios that ignore industry, compared to 1.9 per cent and 1.0 per cent for the high and low yield portfolios formed on an industry neutral basis. Incorporating imputation credits leads to a total return premium of 2.0 per cent of high versus low yield portfolios formed without consideration of industry (0.7 per cent pre-tax returns premium plus 1.2 per cent incremental imputation credits), and 2.3 per cent for industry neutral portfolios (1.4 per cent pre-tax returns premium plus 0.9 per cent incremental imputation credits).

Taking an industry neutral position lowers volatility for both low and high yield portfolios. For example, volatility is 17.0 per cent for high yield portfolios formed by ranking across all stocks, decreasing to 16.5 per cent for high yield portfolios formed on an industry neutral basis.

The risk to forming a portfolio without consideration of industry is highlighted by the bear and bull markets formed from the first 3.5 years of the sample and the remaining 13.5 years. In the first 3.5 years, when the whole market lost 4.2 per cent a year, the pre-tax return premium to high yield stocks formed on an industry neutral basis was 0.8 per cent (-2.6 per cent versus -3.5 per cent). But the high yield portfolio formed without consideration of industry earned returns 7.3 per cent below those of the low yield portfolio (-6.8 per cent versus 0.5 per cent).

In contrast, during the subsequent 13.5 years, the best performing portfolio was the high yield portfolio formed without consideration of industry, which earned 10.0 per cent and a 3.0 per cent pre-tax return premium over its low yield counterpart. The pre-tax return premium to the high yield portfolio formed on an industry neutral basis was 1.5 per cent (9.2 per cent versus 7.7 per cent). Stocks without analyst coverage earned below-market returns during the entire 17-year period (3.4 per cent), during the first 3.5 years (-8.3 per cent) and during the subsequent 13.5 years (6.7 per cent).

Conclusion

In ranking stocks by value-based characteristics investors need to decide whether they are trying to pick undervalued industries, or undervalued stocks within each industry. Large-sample evidence from the U.S. suggests that investors are better off ignoring industry in ranking. But this necessarily exposes the investor to the risk that their portfolio of low growth industries will underperform for a decade. Dividend yield is one value signal which is especially important in the Australian equity market due to the tax benefits of imputation. Ranking stocks by dividend yield irrespective of industry has the advantage of maximising yield and therefore tax benefits from franked dividends. But the industry concentration associated with this approach can lead to material underperformance over extended periods. On average over 17 years ending February 2024, there has been a return premium to high versus low yield portfolios of 2.3 per cent including tax benefits of imputation when portfolios are formed on an industry neutral basis. The corresponding premium when portfolios are formed without consideration of industry is approximately the same, on average, at 2.0 per cent. But consistent performance requires accounting for industry in portfolio formation. The U.S. evidence is that investors taking long-only industry bets have a better return for risk trade-off, on average, but the words “on average” are doing plenty of work. There is simply too much association between industry and financial ratios to form factor-based portfolios irrespective of industry.

References

Ehsani, S., C.R. Harvey and F. Li, 2023. Is sector neutrality in factor investing a mistake? Financial Analysts Journal, 79, 95-117.

[i] Ehsani, Harvey and Li (2023)

4 topics