Financial repression is harder this time around

Financial repression has been used in the past as a tool for reducing government debt overhangs. Yet there are some specific conditions required for such an approach to debt reduction to have a material impact. Historically, the existence of such conditions has proven transitory, in turn suggesting that financial repression is less likely to be a viable policy option going forward.

One of the key dynamics over the last decade has been a material increase in government debt levels. The surge in debt levels has been driven recently by expansionary fiscal policies aimed at offsetting a series of major deflationary shocks, including the global financial crisis of 2008 and, more recently, COVID-19.

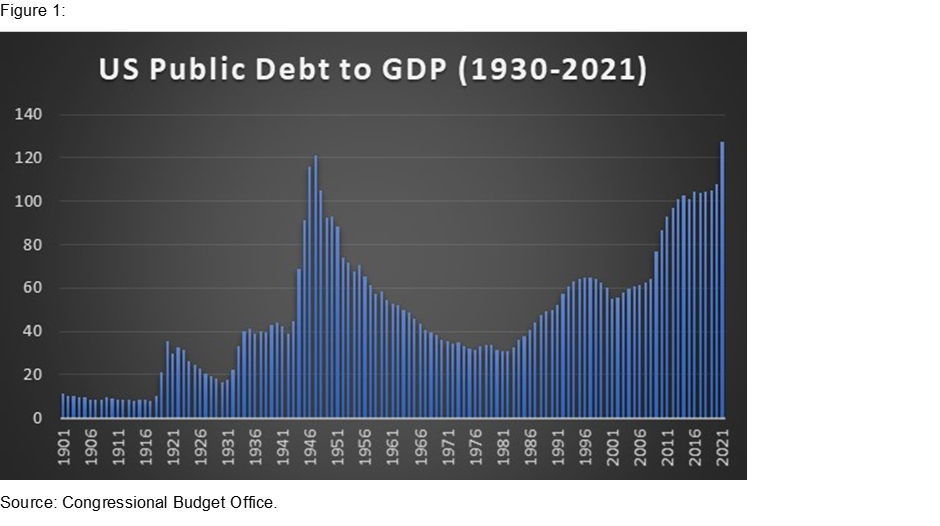

This increase in debt levels is most evident in the US, where the government debt-to-GDP ratio has risen to levels not seen since the end of World War Two.

This dramatic increase in debt levels has created a dilemma for governments; namely how to reduce debt to more manageable levels. Throughout history, debt-to-GDP ratios have been reduced by (a) economic growth; (b) substantive fiscal adjustment/austerity plans; (c) explicit default or restructuring of private/public debt; (d) a surprise burst of inflation; and/or (e) a steady dosage of financial repression. Unfortunately, policies such as raising taxes and/or reducing government expenditure are not only politically unpopular but deflationary in nature. This creates an issue for governments, especially as the deflationary nature of such policies risks undermining the very growth that policy makers are trying to encourage. With this in mind, attention has more recently focused on the risk that financial repression may be increasingly used as a means of reducing government debt levels.

What is financial repression?

In essence, financial repression occurs when governments implement policies to directly channel to themselves the funds that would, in a deregulated or freer market environment, go elsewhere. Explicit policies that channel funding to governments include, but are not limited to, directing lending to the government as well as explicit or implicit caps on interest rates, which limit the interest charged to governments.

Less obvious policies include using reserve requirements to create captive domestic markets for government debt, which would come under macroprudential measures aimed at ensuring the health of the financial system. The political benefit of such policies to reduce government debt is that the impact of inflation and financial regulations are less obvious to the electorate. It is the very opaqueness of financial repression which makes it a more politically acceptable alternative to authorities wanting to reduce outstanding debts.

Financial repression aims to reduce debt levels by keeping nominal interest rates lower than they would have been in more competitive markets. By ‘controlling’ the level of interest rates, the aim is to exploit what are the two interlinked effects associated with financial repression.

The first effect is that the lowering of interest rates associated with intervention policies or other regulations reduces debt servicing costs and is often referred to as a financial repression tax. The second effect occurs when ‘controlled’ nominal interest rates, coupled with inflation, produces negative real interest rates, thereby liquidating, or reducing, the stock of outstanding debt. This is referred to as the liquidation effect. The liquidation effect, in combination with a material level of inflation, is the key dynamic involved in utilising financial repression to reduce debt levels. This effect is on top of the government earning the financial repression tax, so if inflation can be raised materially, then the government also benefits from the liquidation effect.

The requirement for material levels of inflation to generate a meaningful liquidation effect creates issues in identifying which factors are driving the reduction in the debt overhang. Though the impacts of financial repression and inflation are often grouped together, in practice they are quite distinct. The problem arises as one can have financial repression without material inflation and material inflation without financial repression. However, generating a material liquidation effect requires both financial repression and material inflation. It is this interaction that raises the issue of separating the impact of financial repression from that of unexpected inflation. This occurs because the impact of regulated interest rates combined with material levels of expected inflation is similar to that from higher levels of unexpected inflation without financial repression, i.e. materially negative bond rates over an extended period of time reducing the debt overhang.

The financial repression era: 1945 to 1980

To better understand how these dynamics interact within a developed country, it is useful to take a closer look at the experience of the United States from 1945 to 1980. Work by the International Monetary Fund (2015) on financial repression identified that, globally, interest rates were significantly lower in advanced economies between 1945 and 1980 than in freer markets before World War One and the Great Depression of the 1930s, and after financial liberalisation in the 1980s. This has resulted in the period from 1945 to 1980 being identified as the ‘financial repression era’.

For advanced economies, real ex-post interest rates were negative in about half of the years of the financial repression era compared to less than 10% of the time since the early 1980s. This has resulted in this period being identified as one where, for an extended period, governments in developed countries utilised financial repression to reduce the debt overhang from World War Two. Such behaviour is in marked contrast to the debt overhangs following World War One and the Great Depression, which were resolved largely by widespread default and explicit restructures.

To better understand the evolution of the impacts from financial repression over this period, it is important to note the evolution in the financial system caused by the post-Great Depression environment. Most notably, between the Great Depression and the end of World War Two, not only had financial globalisation been dramatically scaled back and capital controls introduced, but governments in advanced and developing countries increasingly shifted towards domestic funding. Unlike the relatively free capital markets associated with the gold standard (pre-World War One), the post-World War Two financial environment was much more regulated and domestically focused. The environment in the ‘financial repression era’ was accordingly well suited to utilising the liquidation effect to lower debt-to-GDP levels.

Though the conditions were suited to financial repression, the existence of regulations and capital controls were not sufficient to generate a liquidation effect. This is better illustrated by considering that whilst the period from 1945 to 1980 may be referred to as the ‘financial repression era’, there were marked differences between sub-periods within the timeframe. It is, therefore, useful to separate the total period into three main sub-periods:

- 1945 to 1956: The immediate post-war decade that was marked by both higher inflation and a public use of controls as a legacy of the war years.

- 1957 to 1968: The ‘heyday’ of the Bretton Woods era that was marked by material capital controls associated with the Bretton Woods agreement and relatively modest inflation (1).

- 1969 to 1980: The unravelling and eventual collapse of the Bretton Woods era as inflation rose dramatically and the capital controls associated with the Bretton Woods arrangements broke down.

Accordingly, when one considers the factors driving the decline in debt-to-GDP levels, the impacts of financial repression and unexpected inflation will vary over time.

Inflation is key to the liquidation effect

Separating the impacts from unexpected inflation and financial repression on debt levels is problematic given their interaction. Whilst acknowledging this complexity, considering the separate sub-periods may assist in highlighting the changing dynamics impacting the effectiveness of financial repression as a policy for reducing government debt.

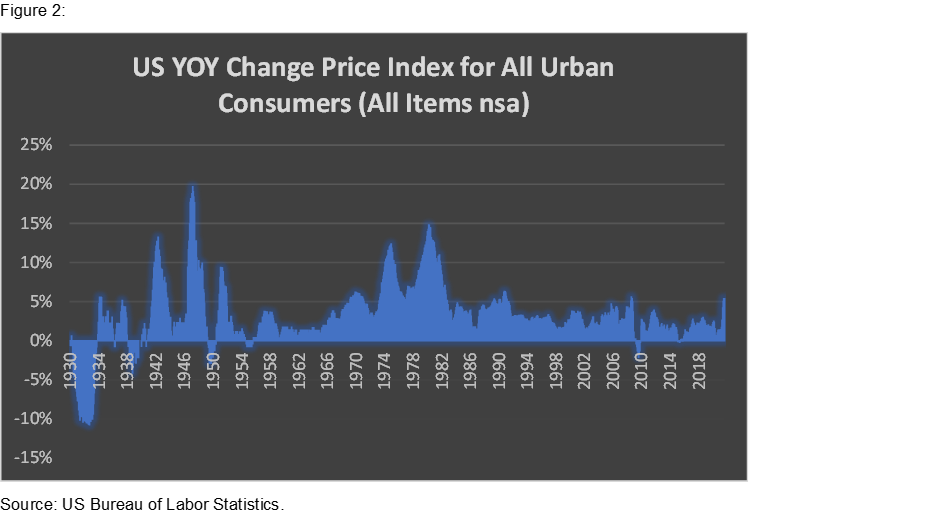

Focusing on the US experience, 1945 to 1956 appears to be the optimal period for exploiting the liquidation effect as capital controls and high inflation (see Figure 2) combined to help reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio from over 120% to under 60%. Indeed, it is this period that would appear to be the period of maximum financial repression. In contrast, the materially lower inflation environment between 1957 and 1968 reduced the impact of financial repression despite there still being capital controls in place.

By the time higher inflation once again became an issue in the 1970s, the dismantling of capital controls would have potentially limited the scope for financial repression to drive a liquidation effect. Indeed, as the period progressed, it is likely that more of the liquidation effect between 1969 and 1980 was the result of unexpected inflation rather than financial repression. The changing dynamics highlight that for financial repression to generate a material liquidation effect there needs to be not only capital controls but also materially higher inflation, i.e. into the double digits.

Conversely, it is possible for a reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio to be generated from unexpected inflation without the existence of financial repression. Accordingly, though we can be reasonably confident that immediately following World War Two the conditions were in place for financial repression to be pivotal in driving the liquidation effect, as we progress past the mid-1950s it becomes less clear cut.

As the scope of financial markets and investment opportunities has widened substantially since the 1970s, it has become harder to implement financial repression. This is not to say that at the margin there may not be some form of financial repression via bank reserving requirements or coercion to buy government bonds. Yet if the decade after World War Two provides any lessons, financial repression cannot be undertaken to materially reduce debt levels without creating material capital distortions.

In effect, creating a regulatory regime consistent with generating a material liquidation effect would require unwinding the internationalisation and integration of the global economy over the last 40 years. In the absence of a major geopolitical event, such a reversal of globalisation would appear unlikely. With financial repression off the table as a policy tool, and unexpected inflation unlikely to be high enough to generate material deleveraging, policymakers may be forced to concentrate increasingly on growth to reduce debt-to-GDP ratios. Such a bias increases the likelihood that policymakers will continue to undertake pro-growth policies and, where possible, take advantage of modest levels of unexpected inflation to reduce debt levels.

For bondholders, the result may still be ongoing low, or even negative, real yields over the longer term; though the drivers are more likely to be unexpected inflation, coupled with low cash rates, rather than material levels of financial repression.

(1) Bretton Woods agreement (formally from 1945 to 1971) involved the introduction of fixed exchange rates within a quasi-gold standard arrangement whereby the US dollar (USD) was fixed to the gold price and other currencies were in turn fixed to the USD. With the introduction of fixed exchange rates came regulations tightly controlling both domestic and international capital markets.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

4 topics

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...

Expertise

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...