Five things to watch for if Australia can nail a soft landing

The Australian economy is in the cross-hairs of an economic dilemma. On one hand, we have what the world wants – our commodities, our world-leading standard of living, and beaches that tourists dream of visiting our shores for. On the other hand, our heavy exposure to the Chinese economy and a decades-long rise in house prices are threatening to burst the utopia.

The data also tells a remarkable story of its own. Inflation is 6.1% on a quarterly basis, or 6.8% if you use the ABS' new monthly CPI indicator which analyses about 70% of the existing "basket". GDP growth continues to remain resilient, though that is thanks in large part to humongous commodities exports. Like much of the Western world, we also have a very tight labour market - but wage growth is nowhere near the pace of inflation. Finally, the lack of affordable housing has (at least according to one academic report) created a $2.6 billion black hole in some of regional Australia's most attractive destinations.

So who will win the war? The optimists or the pessimists?

This wire will examine the reasons for and against an Australian soft landing, with the help of two market professionals who deal with that very question every single day.

Do what I say...

If you've listened to any central banker over the past nine months, chances are you've heard the phrase "whatever it takes" used. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has used it twice. At first, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when he said he'll do whatever it takes to keep the US economy from shutting down completely. Now, he says he has to do whatever it takes to bring inflation (which has an 8-handle in the US) back to its long-run target of 2%.

Here in Australia, Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe has displayed a more acute view of the economy. A month after it raised interest rates for the first time in a decade, Lowe noted this at the bottom of the June statement - "the Board is committed to doing what is necessary to ensure that inflation in Australia returns to target over time".

Three months later, at the Anika Foundation's luncheon, Lowe delivered a speech with this line inserted in its body:

The Board is committed to the return of inflation to target. It is seeking to do this in a way that keeps the economy on an even keel; it is possible to achieve this, but the path here is a narrow one and it is clouded in uncertainty.

He went on to add that a sharp global slowdown would make the likelihood of a soft landing even smaller than it already is. So if the RBA can only control a small portion of the story, is there any reason to back the Governor's quiet optimism?

But trade what I do...

The problem for macro-watchers everywhere has always been and is two-fold. It's one thing for an economist to project what a central bank should do. It's a completely different thing for an economist to project what a central bank will do. When the two are mixed up, there can be dramatic consequences.

Nomura's senior economist and Australian-based rates strategist Andrew Ticehurst says the risk for overtightening (that is, too many or too large a size in rate hikes) is very real.

"The downside risk is also built-in, due to the policy approach being pursued. They could easily end up hiking too much, and getting this wrong," Ticehurst tells me.

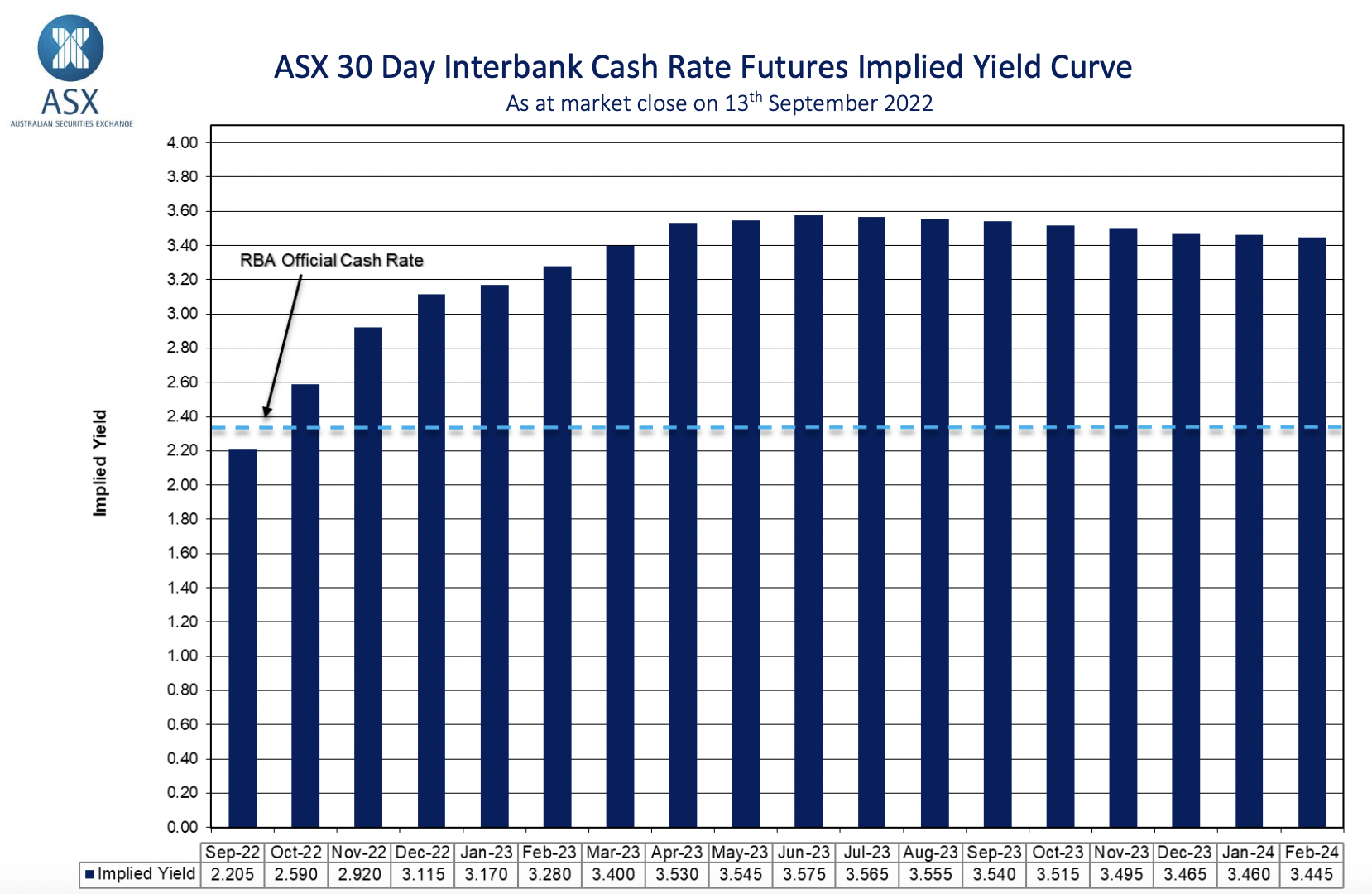

Janus Henderson investment strategist Frank Uhlenbruch specialises in the fixed income market. From a client money perspective, he looks at the RBA's challenge in two ways. For one, the market estimates of the terminal cash rate are really high. You can see this in the ASX OIS curve where traders continue to believe a 3.5% cash rate is the most likely end of this hiking cycle.

But Uhlenbruch believes this rate is far too high, arguing the Reserve Bank's assumption of a 2.5% endgame is far more appropriate.

How can 4% be neutral? And it can only be neutral if you believe the inflation rate is going to be well above for a decade, the RBA's inflation band. We don't agree with that view.

Having said this, Uhlenbruch believes that an Australian 10-year note attracting a 4% yield would offer "outstanding value". This is where he believes the range will peak out - or put in terms an equity investor would understand - at the bottom of the price cycle. Remember, yields and prices move inversely in the bond market. At the time of writing, an Australian 10-year note currently yields about 3.7%.

Watch the house of cards

Housing is the story that keeps on giving. And in Australia, it's been one of the core components of this economy's strength over the past decade. Bulls like Isaac Poole of Oreana Financial Services tend to argue that the hiking cycle will need a pause soon, as the central bank enters what the technicians call "restrictive territory". The argument is that the end to rate hikes may give the housing market a chance to cool but not collapse.

.png)

Bears like Christopher Joye of Coolabah Capital look far more at market data, especially in areas like the housing market. The RBA's housing model is entirely dependent on where that cash rate peaks, and if it goes too far, then an Australian recession could be sparked by severe falls in the housing market or even defaults from owners who can't afford the repayments.

.jpeg)

With all this in mind, it should be no surprise that house prices are a focal point for whether a recession can be averted. Indeed, the experts' base cases are often dependent on their view of house prices. For instance, Janus Henderson's Frank Uhlenbruch has a constructive view of the Australian economy. But this constructive view also comes with the caveat that a 20% fall in house prices is neither improbable nor groundbreaking.

Would it be unremarkable for house prices to go back to the levels they were pre-GFC when the cash rate went to 10 basis points? It would be unremarkable in my view for that to unwind.

Nomura's Andrew Ticehurst also watches the housing market closely. His central case is for a hard landing - a view that is in line with his global counterparts who all have recession calls pencilled in for most major economies. His view, in contrast to Frank's, rests primarily on how the RBA's rate hikes affect the ability of consumers to repay their home loans.

The primary driver of my view is the impact of the interest rate tightening cycle on the housing market and the consumer. The consumer is heavily leveraged, and loan rates have risen and will rise further.

Additionally, he says monthly building approvals and housing finance data from the ABS will provide clues to the size of the downturn in the residential property space. If companies aren't building any more houses and apartments, demand is probably on the way down.

The businesses may make the goods...

Monetary policy has a notoriously long time lag. By some theorists, the impacts of a rate hike could be felt in the real economy only 18 months after the actual decision. But one area that may feel the effects of that hike before homeowners are small businesses. In this spirit, the monthly NAB read on business confidence and conditions is one that Uhlenbruch will be watching very closely in the months ahead.

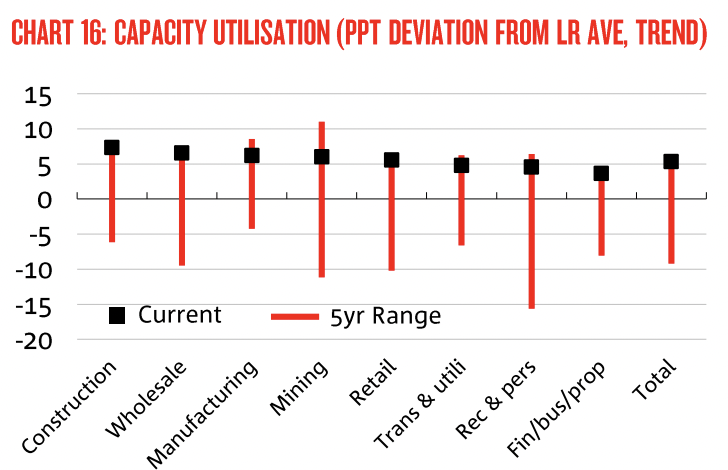

"The [most recent] NAB survey [shows] very strong levels of activity, labour market, capacity utilisation [are all] between one and three standard deviations above their long run levels. The economy at the margins is quite strong," Uhlenbruch says.

The correlation that he is referring to can be found in the following chart:

Uhlenbruch also points to a range of data points that are also near the top of their long term trends, such as capacity utilisation in the labour market. The Australian labour market, much like in other Western economies, is sitting at 50-year lows for unemployment. A record number of people are employed and the definition of "full employment" is being consistently rewritten as we speak.

But it's one thing to employ those people, but how efficient are they? And if the economy is employing all these people, are we using them to create the most output possible? This next chart is an indicator of all that (spoiler: yes).

But the consumer is always right...

But for every business, there need to be a few consumers. Although consumer confidence continues to remain low in the weekly and monthly reads, spending has been telling a different story for some time. The latest read of the Commonwealth Bank Household Spending Intentions Index showed people are still willing to spend up for a range of services from the gym to a new car.

However, the omnipresence of rate hikes and soaring inflation is definitely taking its toll.

Both Uhlenbruch and Ticehurst believe an Australian soft landing will come down to whether the consumer decreases spending by too much.

"I'd be looking at my retail sales just to see what the consumer's doing because that's such a big part of the economy. You can still feel terrible, but you can still spend the money. And there's an element of that I think that we're seeing at the moment. That's how you reconcile poor consumer sentiment," Uhlenbruch tells me.

Alex Shevelev of Forager Funds has already gone one better. In a piece from April this year, Shevelev revealed the Australian shares fund has a very small stake in consumer-focussed companies because the "weighing sentiment" shoe has already dropped.

Note: While the fund's general position on consumer-centric stocks has not changed since the wire was written, Steve Johnson told me that prices have come down to a much more attractive level which reflects the risks in the macro environment.

One more thing

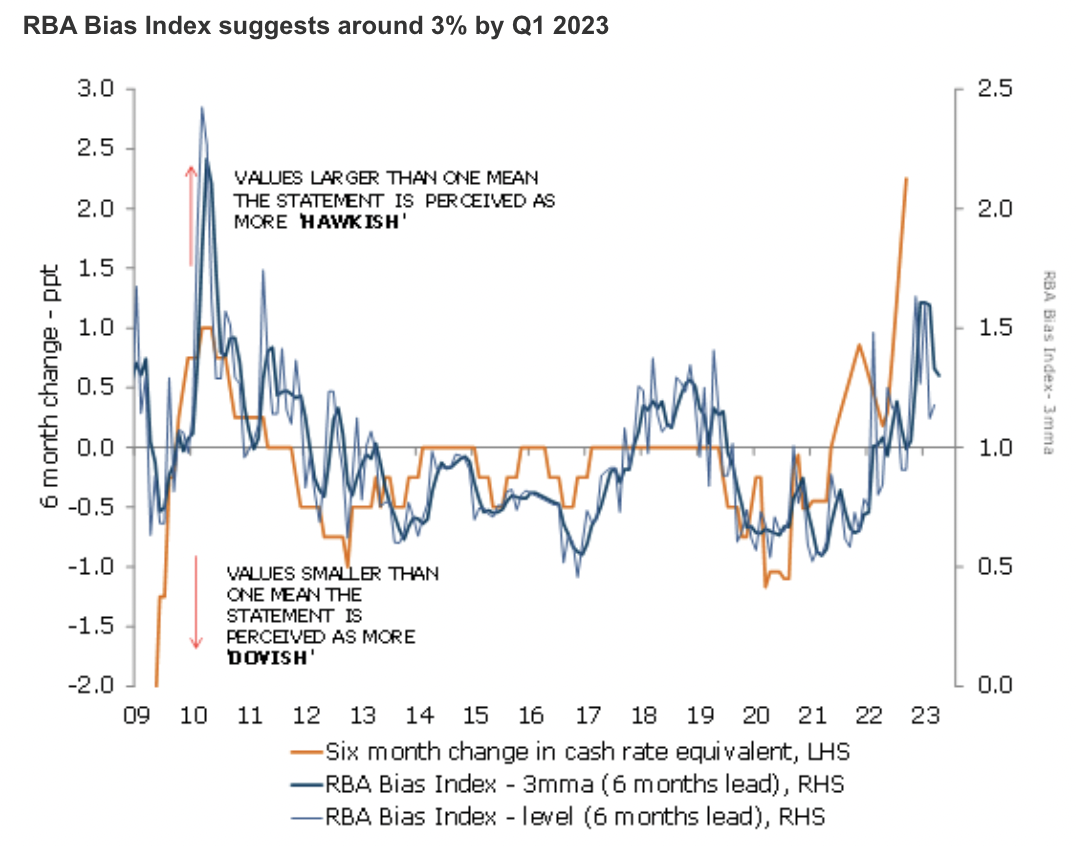

Although we have mentioned four key themes to watch, there is a fifth data point that could be of interest. Market pricing for where traders think the RBA cash rate will be at any point in the near future is usually characterised by the ASX OIS curve. Then, there is the RBA Bias Index - a data point run by ANZ designed to position market pricing against the Reserve Bank's language changes.

The conclusion of the latest read suggests the two are finally moving closer together after more than a year when market pricing was way above the RBA's own expectations. Indeed, both have had to make adjustments as actual events have altered the course of forecasts. Perhaps the answer to the question "who is more wrong?" is actually "everyone"!

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

I'll be in charge of asking the questions to Australia's best strategists, economists, and fixed income fund managers. If you have questions of your own, flick us an email: content@livewiremarkets.com

2 topics

4 contributors mentioned