4 types of equities strategies

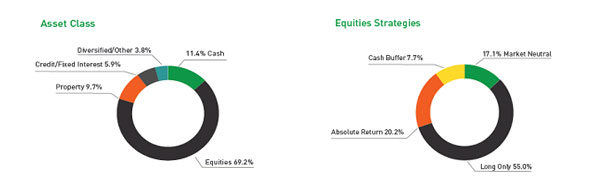

Every month, we provide a snapshot of the Affluence Investment Fund portfolio to our investors. We always include the two following charts to help people understand how we have positioned the portfolio:

The first chart, Asset Class, is straightforward. It shows the exposure the portfolio has, to each of the underlying asset types. The largest asset class is equities (as at 31 August 17) at 69.2%. However, thinking of this 69.2% allocation as a pure exposure to listed stocks is not accurate. This is why we also show the second chart, types of Equities Strategies. This provides a breakdown of the different strategies that make up the 69.2% equities class. We break down the types of equities strategies into four categories:

- Long Only

- Cash Buffer

- Absolute Return

- Market Neutral

Long Only

This strategy is what most people think of when investing in equities. It is when you buy shares with the intention of profiting from an increase in the share price and/or the payment of dividends. However, beyond this there is a huge range of strategies investors can use, such as:

- Active versus passive management.

- Equity size – small cap versus large cap.

- Market sector – resources versus industrials versus biotech etc.

- Investment style – value investor versus growth investor.

- Portfolio concentration – some managers might hold just 10 stocks while others will hold over 100.

- Cash levels – some managers are always nearly 100% invested while others can hold up to 100% cash depending on their outlook.

- Holding periods – some managers take a 5-year view on the companies they buy, while others employ trading strategies and may hold only for the short term.

It should go without saying that all the funds that AIF invests in are actively managed on a benchmark unaware basis. At Affluence we always strive for excellent diversification, so we ensure that our long equities portfolio has a mixture of many of the strategies mentioned above.

Cash Buffer

This is an extension of the Long Only strategy, which we use to categorise managers who almost permanently carry reasonable levels of cash. Some investors don’t like managers holding high levels of cash, as they believe they are being charged management fees for no benefit, or that the individual investor should control the overall level of cash in their portfolio, and expect the manager to be fully invested. While we can appreciate this point of view, we believe that if a manager can continually outperform their benchmark, while holding an average of 15% or more in cash, than this is a wonderful achievement. Holding additional cash allows the manager to act quickly on opportunities that arise (particularly after a market fall), and usually, these managers have lower volatility as well.

Shorting

To understand how Absolute Return and Market Neutral strategies work, it is important to understand what shorting is.

A short sale occurs when the manager borrows shares from their prime broker (usually an investment bank) and sells the shares to generate a cash proceed. As the manager has borrowed the shares from someone else, they are required to return them at some time in the future. To close out the transaction, the manager must buy back the shares on market and return them to the prime broker.

The manager makes a profit if the price of the shares declines in value between the time the manager sells the shares and buys them back again. The manager makes a loss if the value of the shares increases over this period.

As an example, if a manager borrows 100 AAA shares, and sells them for $1.00 each, they generate a cash proceed of $100. If in one months’ time the share price has fallen to $0.80, the manager can buy the 100 AAA shares they had borrowed on market for $80, and return the shares back to the lender. The transaction is closed, and the manager has made a profit of $20 (sold the shares for $100 and repurchased them back for $80). Conversely, if the share price had increased to $1.20, then the manager would have lost $20.

The above example ignores borrowing costs (you need to pay the prime broker to borrow their shares), trading costs, and potentially dividends that need to be accounts for if the company pays one during the shorting period.

Shorting can be a great way to add additional value to a portfolio, particularly when markets are falling and you might appreciate it most. However, it does introduce some risk factors:

Markets tend to go up over time, and thus in any strategy involving shorting, the manager is to some degree, swimming against the tide. It is a riskier strategy than the usual long-only and requires significant manager skill to execute it well.

Transaction costs, borrowing costs and dividend reimbursements mean it can be costly to hold a short for an extended period and this can eat into profits.

Absolute Return

Absolute return strategies are sometimes known as long-short strategies. It involves the manager purchasing shares (long strategy) that they believe will increase in value, while at the same time shorting shares they believe are overvalued and will fall in value.

When done well, this strategy can produce outstanding returns if the long portfolio increases in value and the short portfolio decreases in value. Obviously, if the opposite occurs it can magnify your losses.

The use of shorting increases the overall leverage of the portfolio. Absolute return managers often quote both the gross and net exposure of their portfolios. As an example, if a portfolio was 100% long and 30% short, this would translate to a gross exposure of 130% (100% plus 30%) and a net exposure of 70% (100% less 30%). The gross exposure is an indicator of leverage in the portfolio. For every $1 of equity invested in the fund, you have exposure to the market of $1.30. As with any leverage, this can magnify gains and losses. Net exposure is an indicator of how much market (or beta) exposure the portfolio has. In theory, if the market falls and you have a net exposure less than 100%, the portfolio should fall by less. In practice, it obviously very much depends on what shares you own long and short, and what the reason for the market falls was.

Like the long-only managers, absolute return managers can use all the same strategies for managing their portfolios. However, the absolute return managers also have the following additional factors to consider:

Level of long and short positions. This can range from conservative (say 70% long, and 30% short) to aggressive (200% long, 100% short).

Some managers will sometimes be long individual shares, and short an index rather than individual shares to remove some of the market exposure.

Market Neutral

This is a further extension of the absolute return strategy. With a market neutral strategy, the manager has an equal amount of long exposure as short exposure. For example, they may be long 100%, short 100%, resulting in a gross exposure of 200%, however net exposure of 0% (hence market neutral). The strategy makes a profit if the long portfolio outperforms the short portfolio. Often, trades are organised in “pairs”. Pairs are typically in the same sector, and the manager buys long the company they believe is relatively undervalued and sells short the company they believe is relatively overvalued (for example they may go long BHP and short RIO in equal proportions). It is called market neutral, because if resource stocks all decline or increase by 5%, then this market movement is cancelled out by being equally long and short in the same sector.

There is no Miracle Strategy

It’s important to note that no one strategy is going to outperform all the time! In next month’s article we will explain the pros and cons of each type of equities strategy, and the conditions they may perform well in.

3 topics