Getting Fed up with rate hikes?

Are we done with rate hikes? Or can’t rule them out? Or should we be preparing for rate cuts?

It might seem as though more than ever, there is a lack of agreement about where monetary policy is headed. Generally, that tends to be the case around turning points in the cycle.

And for financial market participants, whether the US Federal Reserve could be done with hiking interest rates has been the burning question. Markets have ruled out further hikes altogether and anticipate over 100 basis points of cuts by the end of next year. In a Reuters poll out of 100 economists, 87 expect that the US Federal Reserve is done hiking rates, while the remaining 13 expect that one more could occur.

At the heart of the issue is the strength of the US economy – is there enough evidence to say that inflation is under control? Has the economy weakened sufficiently, or at the other extreme, is a recession on the cards?

This scenario might seem like Deja Vu, because, we have been here before. There have been at least a few times in the past year where it seemed as though the Fed would be done raising rates, only for the central bank to turn around and hike rates once again.

Is this time different? In some ways, yes, but there are also valid reasons why Fed officials are far from confirming an end to a rate hiking cycle. Indeed, all it takes is a renewed upswing in the economy and inflation, and the prospect of more Fed rate hikes would be back on.

Here we present three reasons why the Fed is probably done, and three reasons why there should be caution in drawing that conclusion once again.

Firstly,

1. There are the signs that the US economy is slowing:

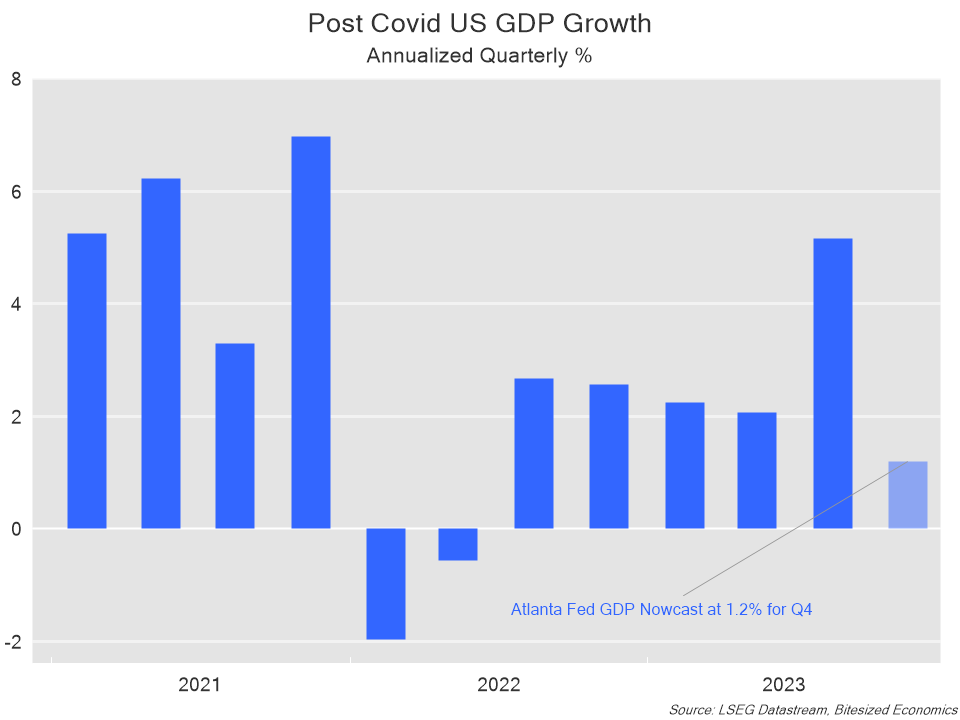

After a very strong third quarter of 4.9% growth, it does appear that growth in the US economy is moderating. The Atlanta Fed nowcast (which tends to do quite a good job at predicting GDP outcomes) is estimating annualized growth of 1.2% in the final quarter of 2023. Moreover, a range of other partial indicators including PMIs and business surveys also point to an easing in activity.

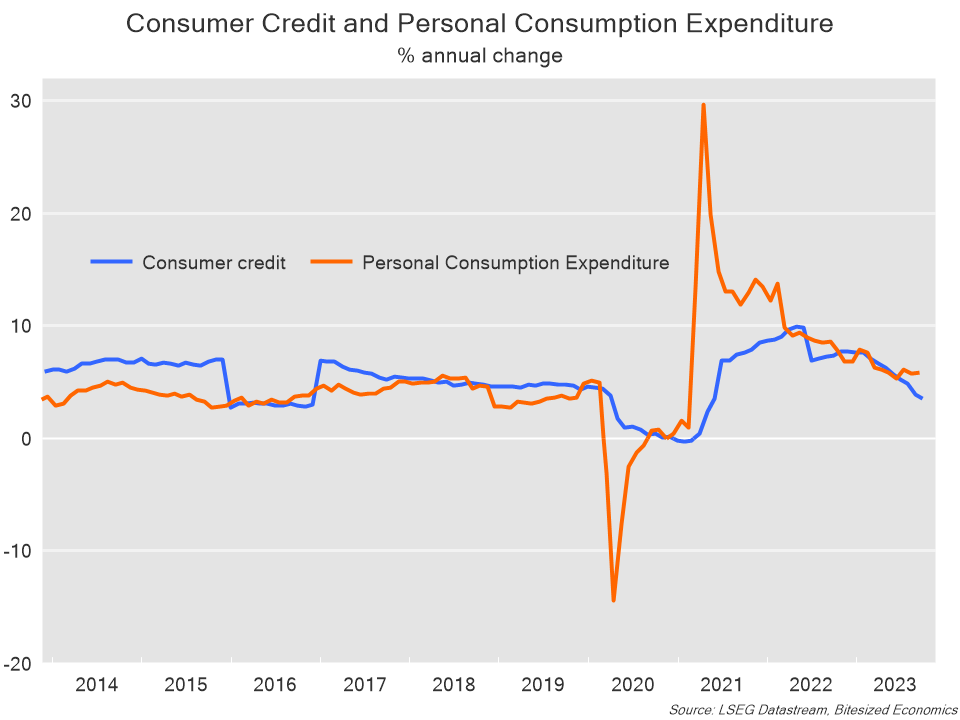

Credit growth is slowing, which could translate into weaker spending:

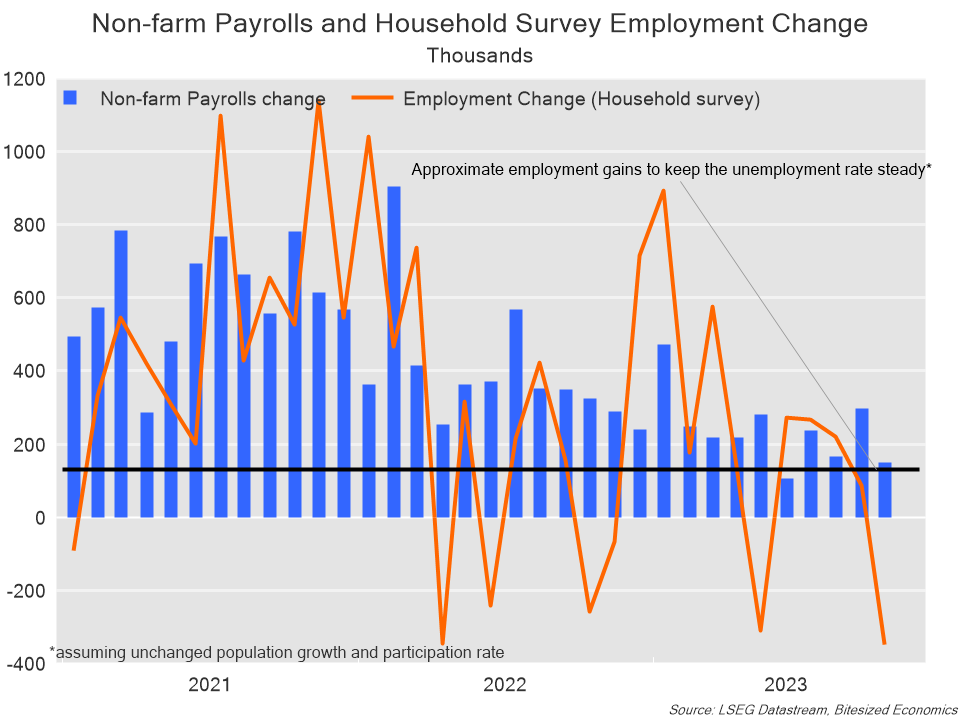

3. The labour market has weakened:

The softening in the labour market is the big one – probably the most convincing piece of evidence to suggest that the Fed may have now done enough. Time and time again, the labour market has surprised with its strength, ever since the economy has recovered from the pandemic. Nonetheless, employment growth has softened. On average, job gains as estimated from non-farm payrolls are still above the line in the sand of around 130k jobs per month. We would need to see employment gains below 130k for a meaningful rise in the unemployment rate. However, it is a different story when it comes to the household survey, which is what the unemployment rate calculation is based on. In this survey, employment gains have averaged just 32k per month over the past six months.

Those weaker employment gains (along with a pickup in population growth) have helped bring the unemployment rate up to 3.9%.

The bigger question is whether these soft conditions in the labour market will persist. Other labour market indicators suggest a more mixed picture – for example jobless claims continue to point to a very low unemployment rate.

One reason why there is less focus on the household survey employment data is because it tends to be extremely volatile month-to-month as you can see in the chart above.

This brings us to three reasons why the resilience in the US economy witnessed over the past few years could continue:

1. Data is volatile:

Is the current slowdown in the economy simply payback from a very strong economy in the third quarter?

The resilience of the US economy this year has come as a major surprise, recall that growth in the third quarter was above an annualized 5.0%. That sort of growth is usually unsustainable, so it doesn’t come as a major surprise that we would see some slowing towards the end of the year.

Nonetheless, some of this underlying strength in the economy earlier in the year could persist into next year. Indeed, a renewed upswing isn’t out of the question, especially if financial conditions continue to ease.

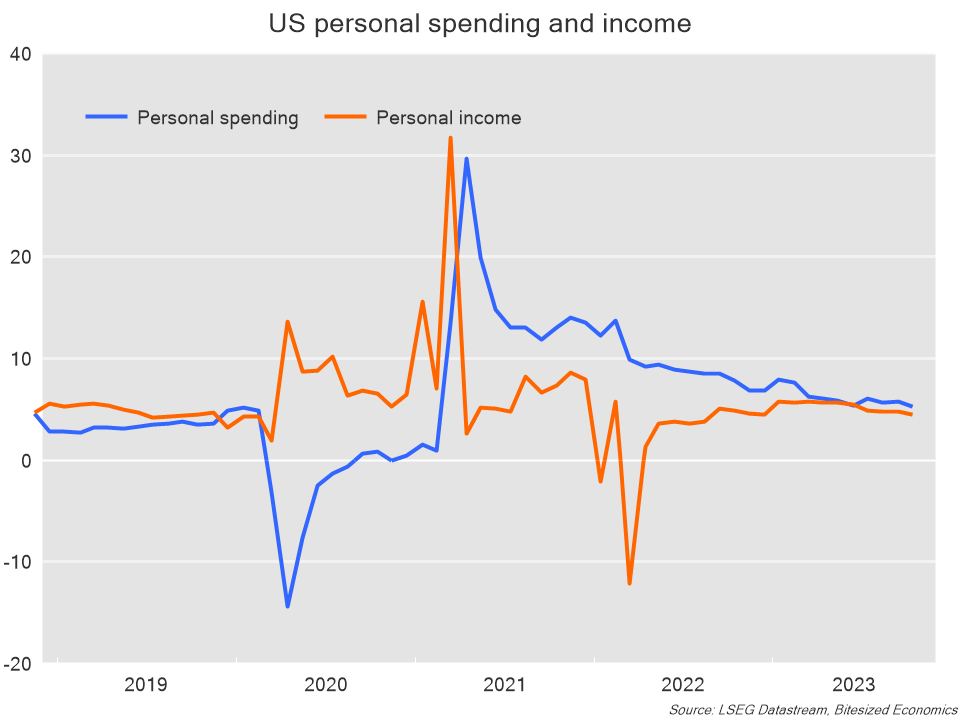

2. Income growth remains strong:

Perhaps one key reason why the US economy has been so resilient is the strength of income growth. Strong growth in incomes and wages continue to support spending, could also slow the process of bringing inflation back down to target.

Despite the strength of growth in incomes, one could argue that spending growth has outpaced the growth in incomes – which is unsustainable. You can’t spend faster than you earn indefinitely, so spending growth will have to slow at some point.

Some commentators have also pointed out that the strong growth in incomes has been accompanied by a recent lift in labour productivity. That would mean that strong income growth isn’t necessarily inflationary, if that income growth comes with more productive workers. However, in reality, productivity measures are notoriously volatile, so it is difficult to read too much into the ‘pickup’ in productivity of the last few quarters.

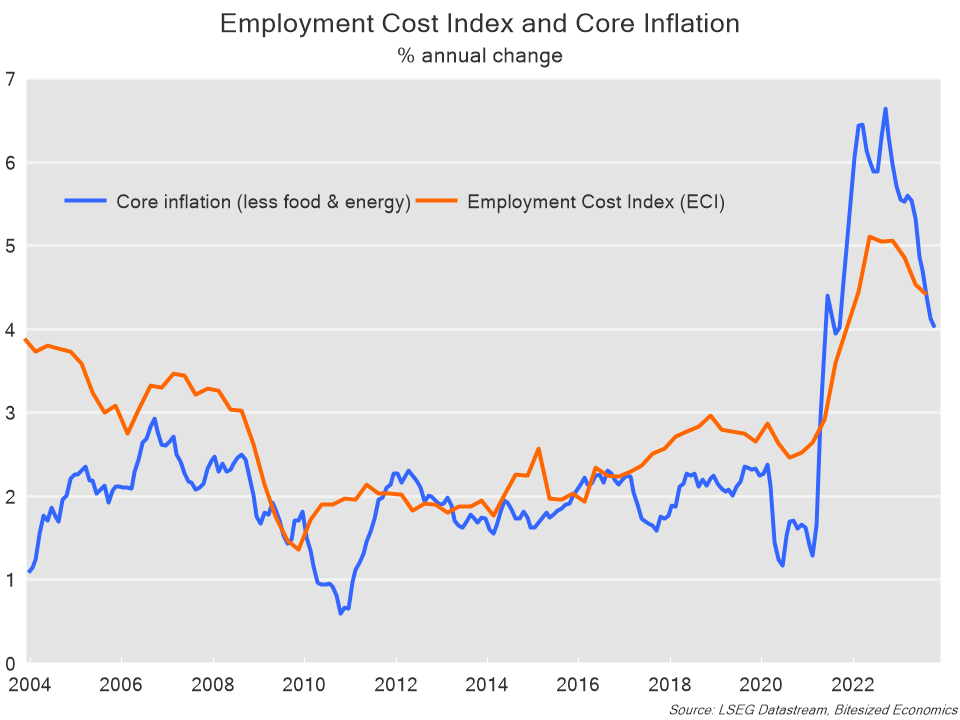

A well-watched measure of wages (the employment cost index) is estimating annual growth in wages and benefits at 4.4%. It’s a slower pace than the 5.1% annual growth recorded in mid-2022, but it probably hasn’t weakened enough to say definitively that core inflation will weaken to 2%.

3. Impact from higher interest rates on spending could continue to be slow:

Finally, a sustained slowdown in the economy relies on tight monetary policy increasingly weighing on the economy. Fed Chair Powell has continually spoken of the lag impact on monetary policy and that the full effects of earlier tightening had not yet taken effect. The question is when will they take effect?

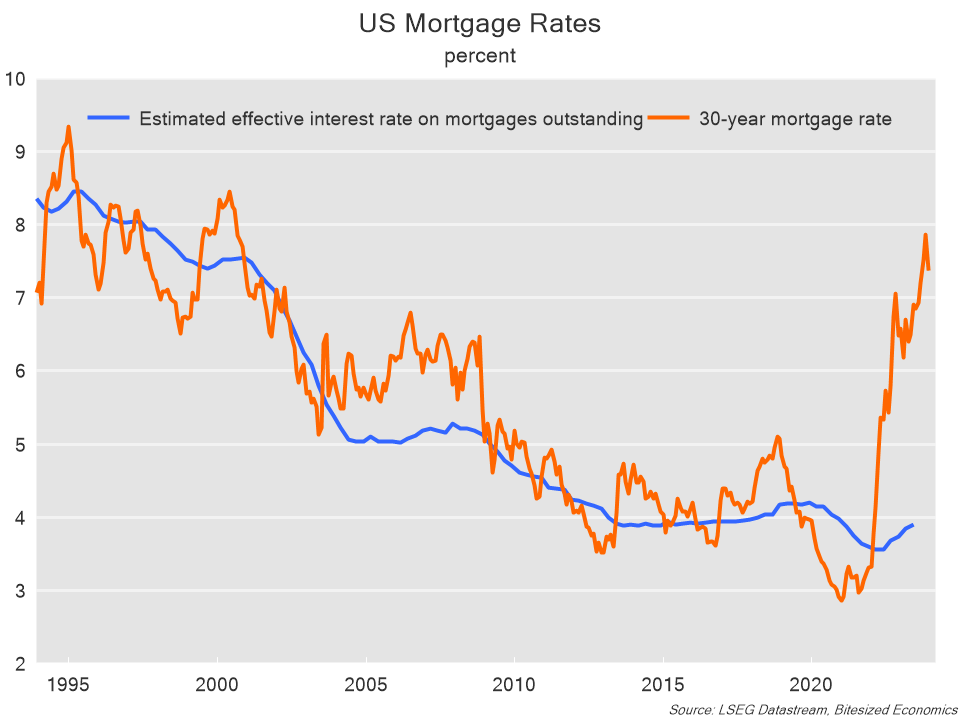

Effective borrowing rates have risen from a trough, but they remain at very low levels. This is the effective interest rates being paid on existing debt. These effective rates extremely low given the high proportion of borrowings on fixed terms, and the low interest rates offered in the midst of the pandemic. It’s a similar story for corporates. While new lending has been hit hard, existing borrowers are less affected. The lagged impact on monetary policy implies that over time, tighter monetary policy will increasingly weigh on the economy, but also that lag could take years.

There is some clear evidence that the US economy is slowing. But this is coming from very strong growth earlier in the year, which begs the question if renewed strength could once again emerge.

For now, the economic slowdown is enough to say “enough”, and that is likely to continue to weigh on the US dollar, bond yields and be supportive of risky assets. But that could be a completely different story next year if inflation or the economy doesn’t ease sufficiently. Alternatively, if a more substantial weakening in the economy is on the cards, that might make large scale rate cuts a greater possibility, although global recession worries also tend to prop up the US dollar and weigh on risky assets.

This time last year, financial market participants were almost unanimous in calling for a global recession in 2023. There is much less of a consensus for 2023, but the outlook still has the same air of uncertainty.

5 topics