Have you been fooled by thematic ETFs?

As part of my gig as a resident expert on the Equity Mates podcast (where I attempt to improve or “pimp” listener portfolios), I’m doing dozens of meetings with self-directed investors each month, discussing (generally) their portfolios and how I think it could be improved.

The most common approach I’m seeing is a low-cost core + satellite strategy, where investors attempt to successfully blend a core of traditional, broad-based index-tracking ETFs with a range of specific satellite opportunities.

In theory, this is great. You use the lowest cost ‘beta’ you can find to get general market exposure and then target specific ‘opportunities’ in your zone of competence to supercharge your returns and outperform.

The issue we see is people seem to be predominantly using ‘thematic’ ETFs to fill this ‘satellite’ part of their portfolio. And while this has certainly worked for some, it’s been less effective for most, with fortuitous timing (luck) being the main differentiating factor (not a sustainable, repeatable investment process.)

We define sector/thematic ETFs as exchange-traded funds that own a basket of underlying securities focusing on industries, trends, or themes such as technology, sustainability, or specific commodities. As opposed to what we’d define as an “index fund” – a market-cap weighted portfolio of securities in a particular geography (think, MSCI ACWI, S&P/ASX 200, S&P 500 etc.)

While targeting these “high growth” and “structurally supported” corners of the market sounds good in theory, as a “passive” investor trying to benefit from the long-term compounding benefits of extreme diversification and regular contributions, why are you potentially (read: probably) diluting your returns and drifting into active management? The reason you use a low-cost “core” for the majority of your capital is because you fundamentally believe that active management can’t outperform on an after-fee basis… and here you are, being active, paying fees…

Sector thematic ETFs underperform

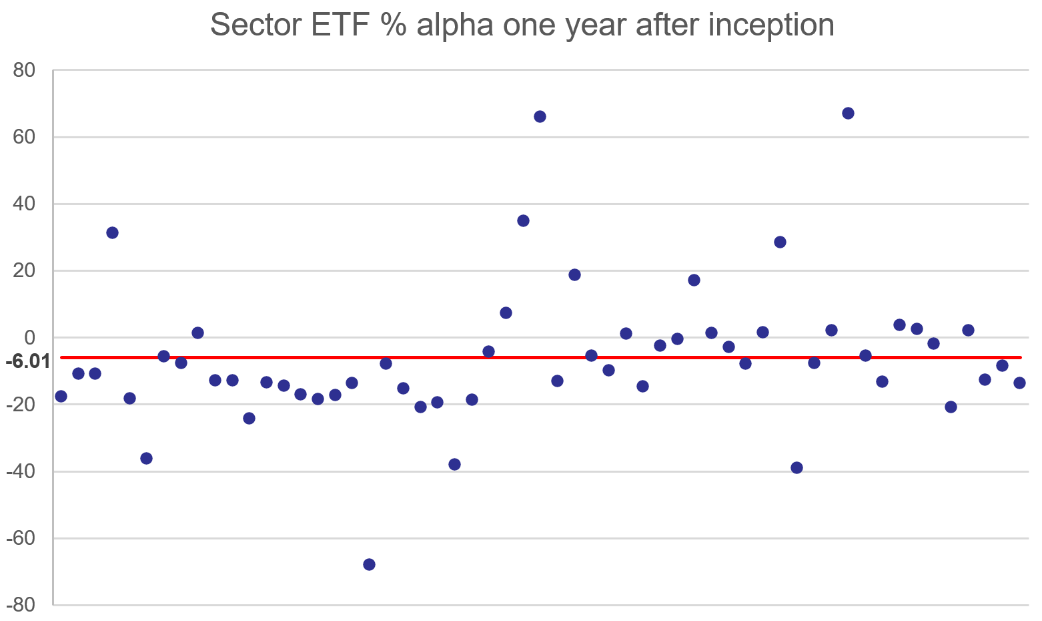

We analysed data (thanks Ben Richards) from 60 sector/thematic ETFs listed on the ASX per the ASX investment product directory, against the MSCI ACWI benchmark (all country world index). 57 of those ETFs have been running for over one year, with an average underperformance vs the index of -6.01% on a total return basis (includes dividends reinvested). 41 out of 57 products underperformed over their respective one year time horizons.

|

1 year |

2 years |

3 years |

|

|

Average alpha p.a. % |

-6.01 |

-5.31 |

-3.85 |

|

Median alpha p.a. % |

-8.61 |

-5.36 |

-2.07 |

Source: Factset, ASX, Seneca Research

Digging beneath the surface, the plot below illustrates the composition of the underperformance of these ETFs.

Source: Factset, ASX, Seneca Research

The underperformance persists over two- and three-year time horizons, per the previous table. While there is a limited sample size over longer time periods (only 10 have been around for more than 10 years), we’d wager that you’ll see similar results in the fullness of time.

Our analysis is supported by Morningstar data, which reports that 75% of thematic funds underperform the benchmark on a 3-year view (and that’s not including those that didn’t even make it to the 3-year mark before closing).

Here are 3 reasons why we think thematic ETFs underperform the market:

1. Investors get lured into buying at peak excitement.

ETF providers, who earn fees on total assets under management, capitalise (prey) on investors' heavy (often, complete) reliance on historical returns as the best predictor of future returns.

“Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome” – Charlie Munger

ETF providers use statistical back-tests, search data and other unique datasets to determine which ‘themes’ have worked in recent times and what will attract strong demand from unsuspecting retail investors. The products are ‘rigged’ to ensure they backtest strongly. The provider's ability to quickly create and launch new products largely determines how much market share they capture during the height of euphoria – whether that be uranium, big tech, AI, semiconductors, or cybersecurity.

2. Growth is (largely) priced in

When you buy a semiconductor ETF (for example) it might be because you think that “the growth of electronics is going to boost demand for semiconductors in the long term”. While that may be true, is this a unique or uncommon perspective?

When making a foray into ‘active’ investing, the only sustainable way to outperform is to be able to identify and exploit an “edge” over the rest of the market – an assumption that you think is mispriced or misunderstood by most. Said semiconductor ETF will own shares in mega-cap companies like NVDA, ASML, IBM etc which are well covered by some of the best, most highly compensated analysts in the world. The chances of the available, public and historical information not being fully and efficiently priced by the market are near zero.

That's not to say that inefficiencies don't arise on occasion, but a thesis that ‘society will require more semiconductors in the future vs today’ is far too simplistic. You need a differentiated view. There are lots of smart people in the market, so you have to ask yourself if the growth you forecast is already baked into market expectations.

I’d argue if you can derive these sorts of insights, why not just buy the underlying securities best placed to capture the growth?

So what should you buy instead?

For investors looking for index returns, which have proved to be more than adequate when compounded over the long term, index ETFs that replicate indices such as the MSCI All World Index are a good starting point. We prefer a general, global exposure like this over a specific geography ETF (e.g. S&P500 or S&P/ASX 200) as it avoids some of the concentration/correlation risks that go with investing exclusively in those markets.

For those looking to generate returns above the basic indices, we think a well-designed factor-based ETF is a good (but sub-optimal) entry into pseudo-active management. Applying a basic factor screen (say, a rudimental ‘quality’ filter) gets you at least some of the value a good active manager offers for 25-50bps cheaper.

“Price is what you pay, value is what you get” – Warren Buffett

For the difference in cost between a factor ETFs and a fairly-priced active, discretionary manager, we think the active managers offer far superior value. Whether it's the underperforming thematic or a not-so-bad factor-based ETFs, investors are getting a raw deal – you only get c.25% of the investment process typically employed by an active manager, yet still pay c.75% of the costs.

How do you identify these active managers?

In previous Livewire articles, I’ve outlined some fundamentals when it comes to successfully comparing and selecting Australian (here) and International (here) fund managers. At Seneca, we employ some of these concepts to manage our range of separately managed accounts (SMA’s) – where investors enjoy all the transparency of a normal stockbroking account, with the benefits of professional, active management across the asset classes.

Core-Satellite is a behavioural bias

In my professional opinion, the ‘core-satellite’ approach is a form of ‘mental accounting’, a behavioural bias in which individuals ascribe different values to the same amount of money. Investors should treat every dollar respectfully and equally, actively managing their portfolio (in totality) towards their stated objectives.

Thematic ETFs exploit our human desire to ‘be successful’ at investing and take us away from our long term goals.

On one hand, most know that for the average person, timing the market is futile and attempting to make discrete investments only detracts (regardless of how sexy the label is) from portfolio returns. This sensible, logical, rational half of our brain invests completely in a low-cost core or outsources to a professional, active manager(s).

On the other hand, most people think they are above-average drivers. Our old friends Dunning & Kruger convince us that we’ve developed some insight from our detailed review of a Reddit forum. We convince ourselves that we’ll be able to ‘get in and get out’ successfully, on the back of hours of confirmation bias-laced ‘research’, interpolating a ‘trend’ on the historical price chart or extrapolating an annualised return from the marketing materials. This “satellite opportunity” is worth deviating from our investment policy…

The “satellite” allows us to feel like we know what we are doing, to believe that maybe, just maybe, we’re smarter than the ‘average investor’ – all without doing much more than reading the label on the tin. Deploying every new dollar in the exact same sensible, risk-managed portfolio is boring. Particularly when the newspapers, online forums and blogs continue to present you with ‘opportunities’, leveraging your fear of missing out to new heights.

Somewhere over the past 15 years, investing has been ‘gamified’. There’s this expectation that it’s supposed to be exciting or entertaining these days. And at times, it is highly enjoyable. However, mostly (and I’m sure most professionals would agree) it is, and always has been, inherently repetitive, tedious, time-consuming, fine-detailed work.

Fortunately, if you can avoid getting distracted by every shiny new product created by the billionaires who own the ETF providers, take a disciplined, long term view, save and contribute regularly to a properly constructed portfolio pushing hard towards your goals – you’ll give yourself the best chance of achieving them (and more).

5 topics

1 contributor mentioned