High risk of US equity market correction

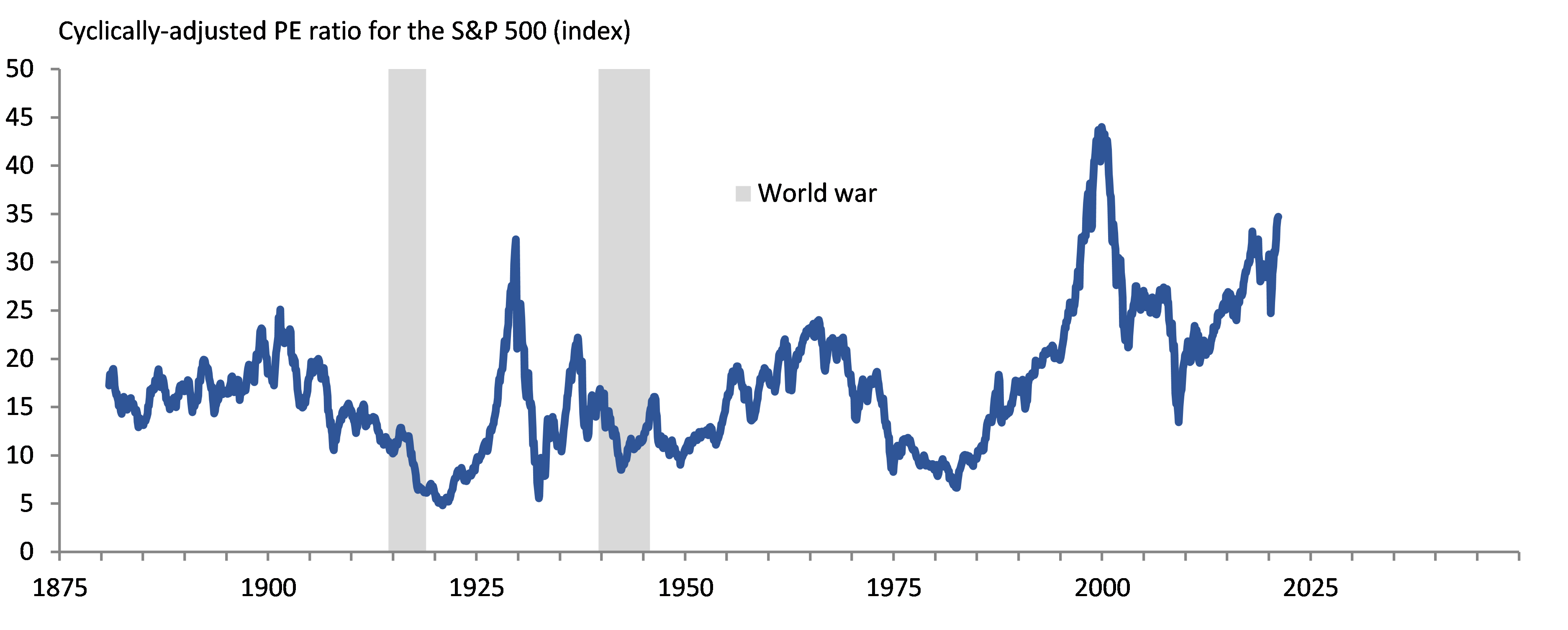

US equities are extremely expensive according to long-term valuation

measures such as the cyclically-adjusted PE (CAPE) ratio. The CAPE ratio for

the S&P500 is currently about 35, which is the second-highest level in the

roughly 140 years for which there are data. The ratio, which was co-developed and

popularised by US academic Robert Shiller in the 1990s, values equities by

comparing real stock prices with average real earnings over the preceding 10 years. This period is meant to

capture the behaviour of earnings over the business cycle, which seems a

reasonable assumption given that the US has averaged one or two recessions per decade

in the post-World War 2 period. Using the average of actual earnings rather than

forecast earnings might seem odd, but recognises the great difficulty faced by equity

analysts when estimating future earnings.

Figure 1: The US cyclically-adjusted PE (CAPE) ratio is at an extreme

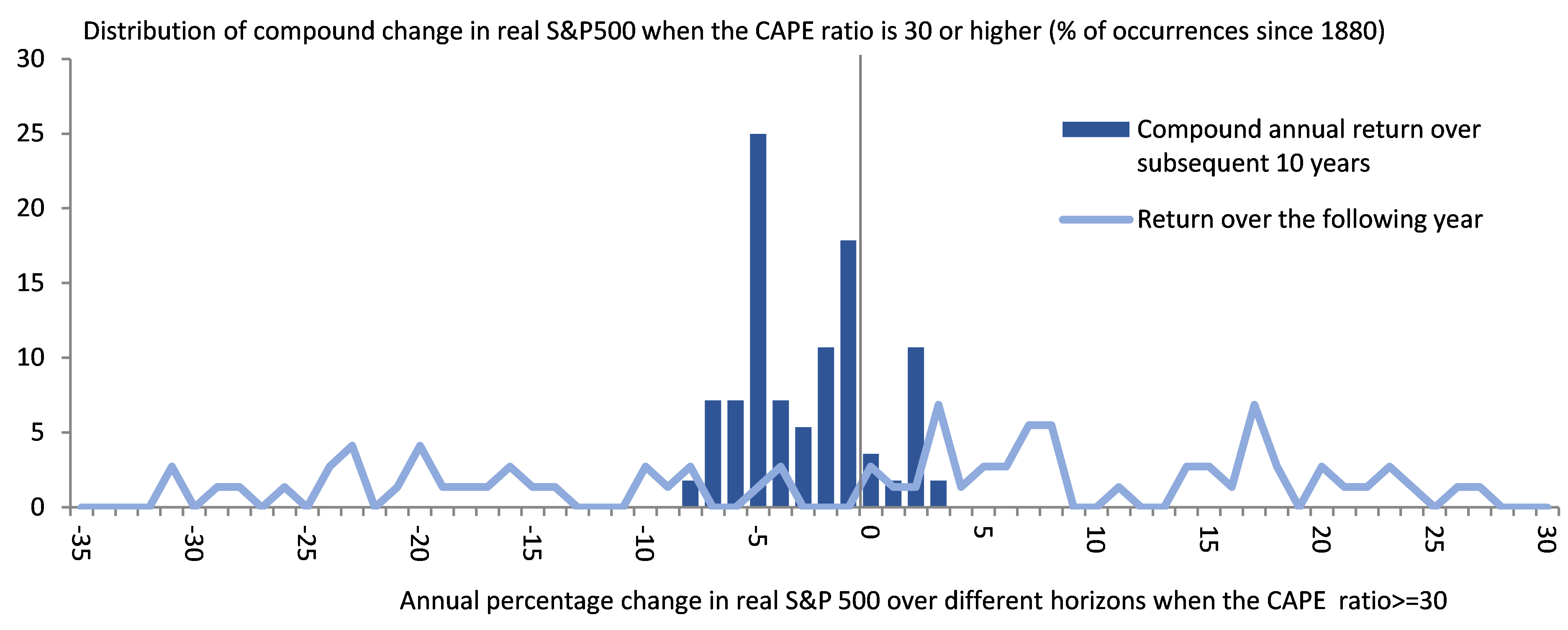

A high CAPE ratio traditionally heralds significant equity market underperformance over the medium to long term.

The CAPE ratio is not designed as a short-term signal of market performance, but, remarkably, it provides useful information on the future medium-to-long-term performance of stock prices. For example, past instances of a high CAPE ratio, where Coolabah Capital Investments (Coolabah) has used a ratio of 30 – which is roughly the long-term average of 17 plus two standard deviations – or more, have generally been followed by a material decline in real share prices over the following 10 years.

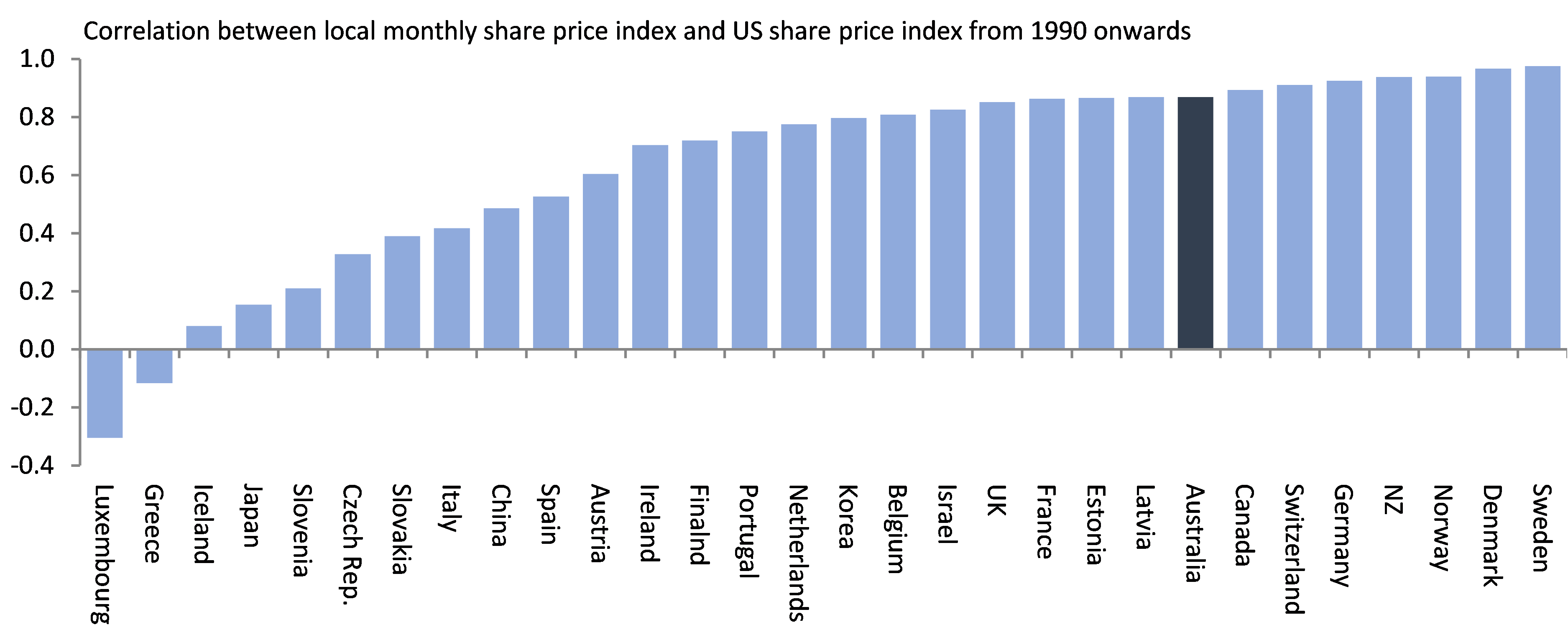

The US stock market's current CAPE ratio of 35 points to a high risk of either a significant market correction or sustained market underperformance. In turn, this raises the risk of a spillover to other advanced economies given most other equity markets have a high correlation with US share prices.

Figure 2: Experience suggests that real stock prices are likely to

fall in the years after the CAPE ratio reaches a level of 30 or more

Note: This chart replicates work by Gerard Minack at Minack Advisors.

Source: Robert Shiller, Minack Advisors, Coolabah Capital Investments

Figure 3: Most advanced economy share markets are highly correlated

with the US market

Note: Share price data start later than 1990 for some smaller economies.

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Robert Shiller, Coolabah Capital Investments

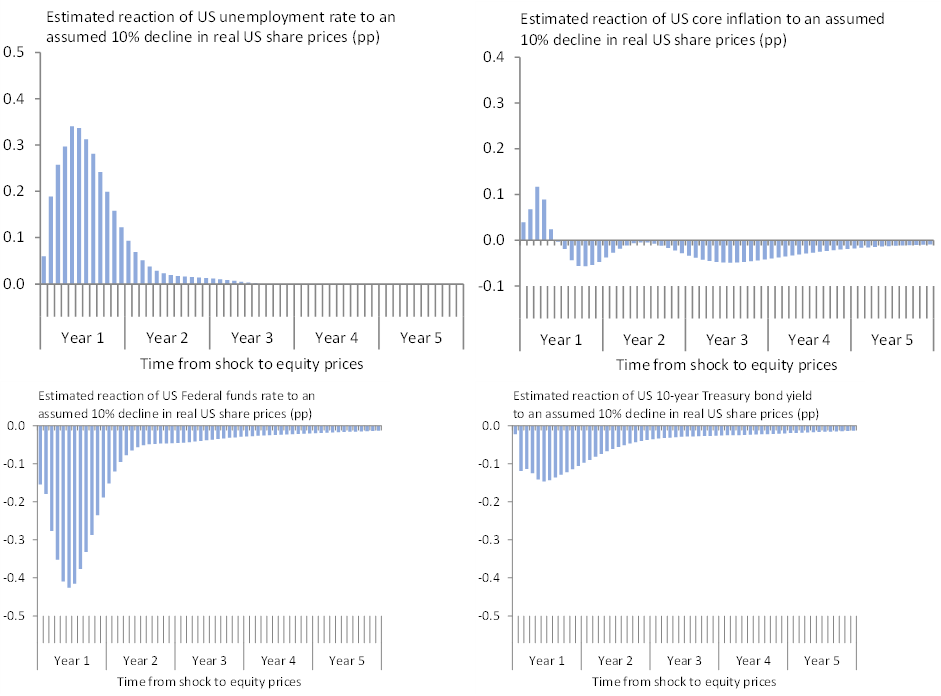

History suggests that a sharp correction in US share prices leads to higher unemployment, slightly lower inflation, and lower interest rates.

Given the growing risk of a correction, Coolabah explored the potential impact of an assumed 10% decline in real stock prices on the US economy and financial markets. We did this using a simple vector autoregression (VAR) model to capture the interrelationships between key economic and financial indicators.

The model results suggest that a 10% decline in real share prices is associated with:

- a sharp 0.4pp rise in the unemployment rate;

- slight downward pressure on core inflation from the increase in spare capacity;

- sharply lower short-term interest rates, with the Federal Reserve quickly reacting to higher unemployment by reducing the funds rate by 0.4pp; and

- a steeper yield curve, with a comparatively smaller decline in the 10-year bond yield of about 0.15pp.

Figure 4: A US share price correction normally has large economic

and financial market spillovers

Note: The charts report generalised impulse response functions from an assumed 10% decline in real US share prices in a VAR model estimated from 1954 to 2020. The model comprised: (1) real US share prices; (2) US unemployment rate; (3) US core inflation; (4) Federal funds rate; and (5) US 10-year Treasury bond yield.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Robert Shiller, Coolabah Capital Investments

The scope for policy rates to react to a slump in share prices is negligible, at least in the short term.

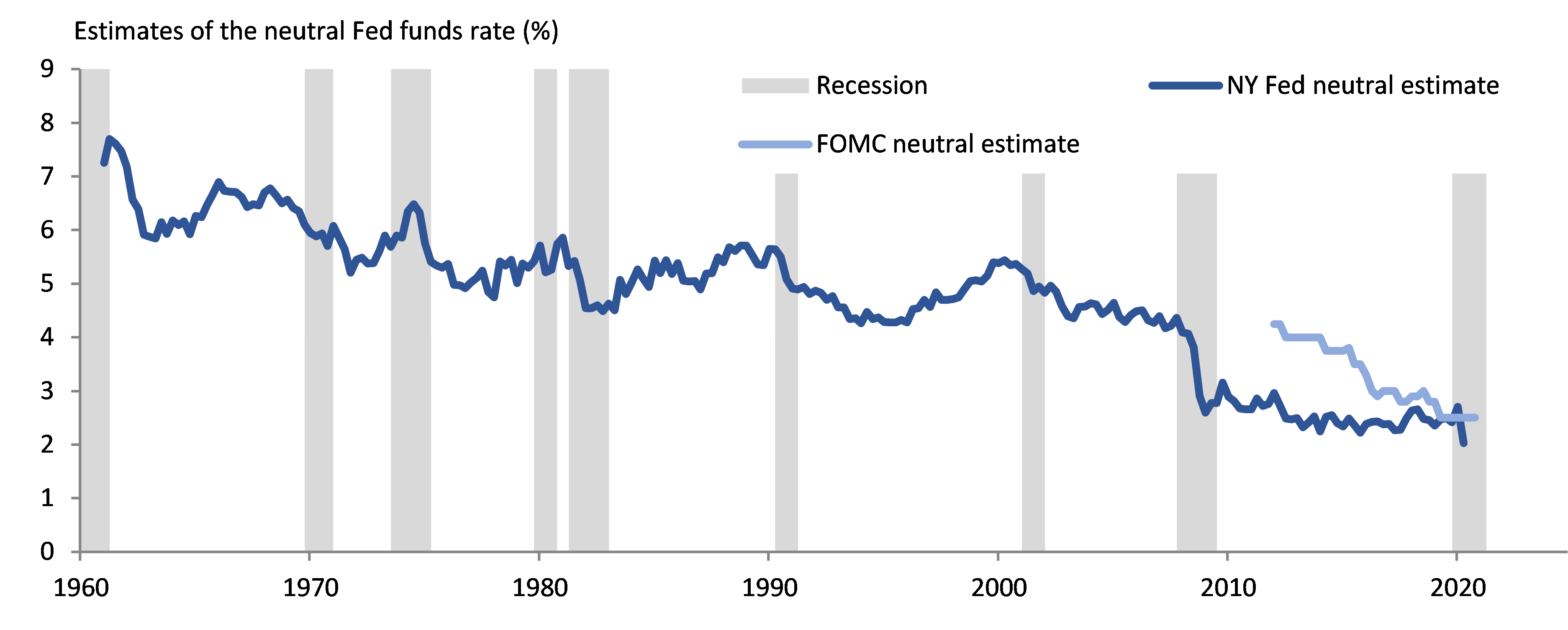

With the US Fed funds rate already near zero at a target range of 0-0.25%, the Federal Reserve’s ability to conventionally respond to a stock-market correction by cutting the policy rate is non-existent, unless the Fed has had the opportunity to start normalising interest rates in the meantime. This is possible given that the CAPE ratio’s signal of equity market performance is medium- to-long-term in nature and with the fixed income market pricing in very gradual rate hikes from mid-2023 onwards. That said, the median forecast of Fed policy-makers is for the funds rate is for it to remain unchanged until at least the end of 2023, while the Congressional Budget Office forecasts that the funds rate will remain in the 0‑0.25% target range through to 2024, with gradual rate rises commencing in 2025 and the funds rate not reaching the Fed’s estimated neutral nominal funds rate of 2-2.5% until the late 2020s (the New York Fed estimates the neutral nominal rate at 2%, while the Federal Open Market Committee put it at 2.5%).

Bond yields are likely to react more to a stock-market correction than in the past, as the central bank undertakes additional QE and potentially deploys other unconventional measures.

With conventional monetary policy likely to

remain constrained and anchored by a low neutral interest rate, long-term bond

yields may react more to a stock-market correction than suggested by the above

modelling. Barring a material and speedy

fiscal stimulus, this is because the Federal Reserve would likely undertake

additional QE. Depending on the size and duration of the shock, the Federal

Reserve could also consider other unconventional policies, such as adopting negative

interest rates. Federal Reserve Chair Powell indicated

last year that the Fed remains averse to negative rates – where former Vice

Chair Fischer said

this aversion was so great in the early 2010s it led to the Fed keeping rates

lower for longer than would otherwise be the case – but the tide may be turning among central

bankers, with the International Monetary Fund recently arguing

that, “the evidence so far indicates negative interest rate policies have

succeeded in easing financial conditions without raising significant financial

stability concerns”. As the IMF put

it, “ultimately, given the low level of the real neutral interest rates, many

central banks may be forced to consider sooner or

later, even if there are material adverse side effects”.

Figure 5: The US policy rate

is near zero anchored by a multi-decade low in the real neutral rate

Note: Assumes that the Federal Reserve’s inflation target is 2% for the entire period.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, National Bureau of Economic Research, Coolabah Capital Investments

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 13 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch

5 topics