High-yield bond market blows (again)

In the AFR today I write that the global high-yield (or junk) bond market is blowing up once again, schooling investors on why the interest rates on these securities need to be so high. The classic local case was the superficially enticing 8 per cent yield offered on the $325 million of Virgin Airlines’ senior unsecured bonds, which listed on the ASX in November. That sounded like a terrific deal until the airline went bust months later, all but zeroing the value of this investment. Click on that link to read the full column or AFR subs can click here. Excerpt enclosed:

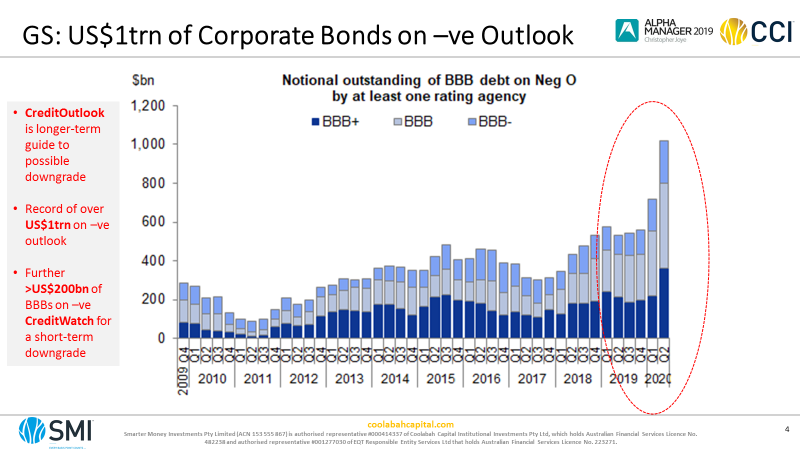

On our numbers, there are more than $US1 trillion ($1.53 trillion) of BBB-rated "investment grade" bonds that have been put on "negative outlook" by credit rating agencies to be possibly downgraded in the future (many into the "junk BB" or lower band).

This is a record, and more than double the value of BBB bonds at risk during the last big credit blow-up in 2015 and triple the value of BBBs that were on outlook for a downgrade in late 2009.

There is a further $US200 billion of BBB bonds that have been placed on the more dangerous “negative watch” footing by ratings agencies for an imminent downgrade.

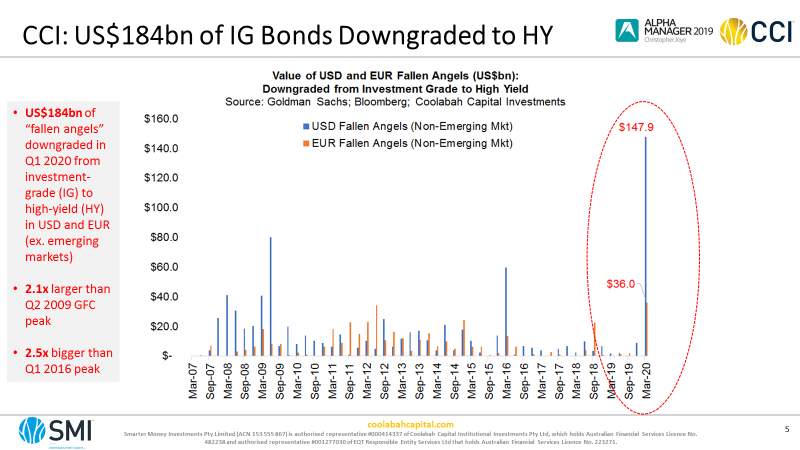

We carefully track “fallen angels”, which are bonds that were once investment grade (ie, rated BBB- or higher) that have been downgraded into the high-yield/junk category (ie, BB+ or less).

In the first quarter of 2020, there was a record $US184 billion of fallen angels in US dollars and euros (excluding emerging market debt), which is 2.1 times larger than the previous peak in fallen angels recorded in the second quarter of 2009. It is also 2.5 times bigger than the fallen angels recorded in the last credit shock in the first quarter of 2016.

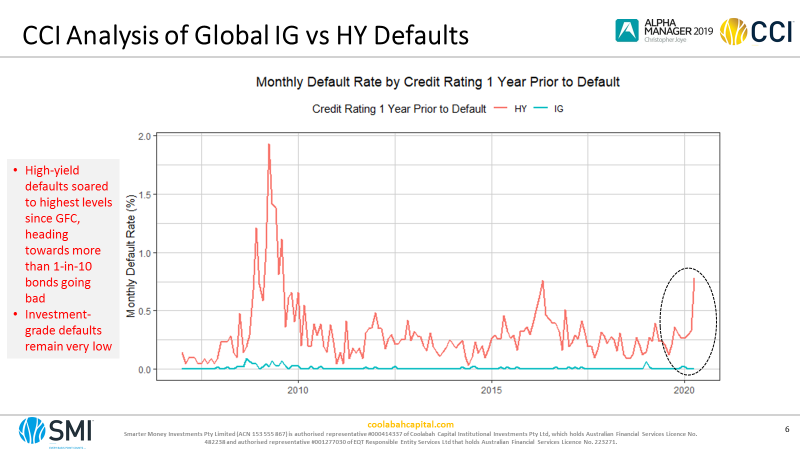

We also track default rates for both investment-grade and junk bonds around the world. While investment-grade defaults are almost non-existent (using the credit rating one year before default), high-yield defaults have soared to more than 0.75 per cent per month (or more than 9 per cent on an annualised basis), which is the biggest increase in defaults since the global financial crisis.

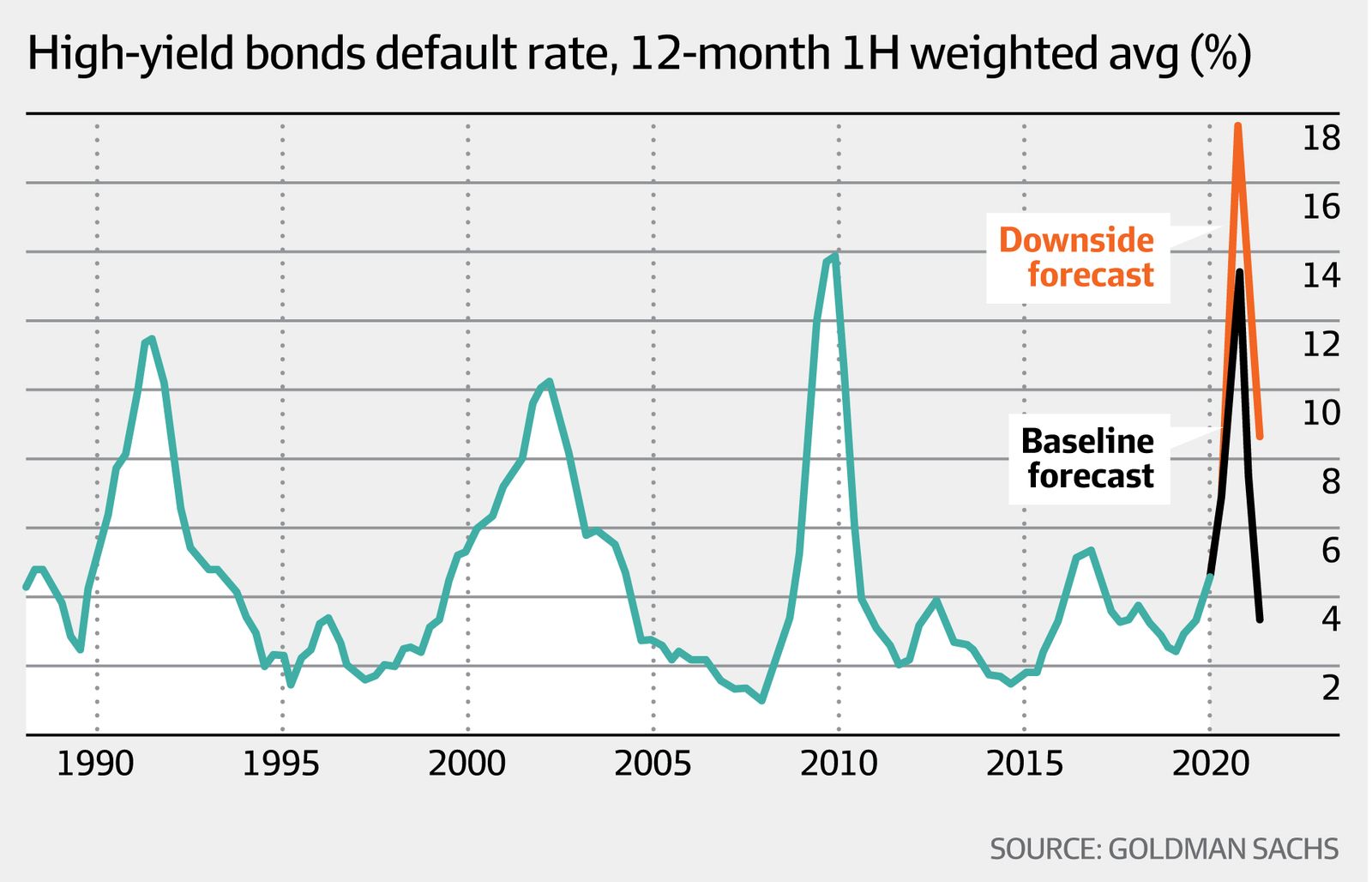

Goldman Sachs is forecasting that the 12-month default rate on high-yield bonds will climb to more than 13 per cent, converging on levels last experienced during the GFC. That means more than one in 10 of these securities will sour.

Readers might recall that this column repeatedly warned of the burgeoning risks in global high-yield debt investments. These hazards have been amplified by the massive growth in BBB-rated bonds, which now represent more than half of all investment-grade debt compared with just 17 per cent in 2001.

Gross leverage in the BBB sector, which is calculated as total debt divided by 12-month earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation, is also at its loftiest level ever and above the peak recorded during the GFC.

While we can invest in high-yield debt, we have had several concerns. The first has been the risk of a jump in fallen angels downgraded from investment-grade to junk, driving forced selling from funds that cannot invest in high yield. And it is clear in this shock that the rating agencies have itchy trigger fingers, even putting Australia’s sovereign rating on negative outlook when it is arguably one of the best-placed AAAs in the world.

A second worry has been the surge in zombie companies, such as Virgin, which are having to dedicate all their earnings (if they have any) to service interest repayments on their debt.

We hunt zombies in real time and have documented a stunning increase in their proliferation in listed markets. If you combine the rise of zombies with the record leverage among profitable investment-grade corporates, you have a Molotov cocktail that is bound to ignite in any serious shock that hammers revenue, such as the great virus crisis has done.

It is not surprising, therefore, that we are seeing a raft of “distressed debt” funds seeking to capitalise on the wave of high-yield bonds teetering on the brink. Especially affected sectors obviously include retail, commercial property, energy, transport and tourism.

In this context, it was interesting to hear that the Reserve Bank of Australia has decided it will for the first time lend against corporate bonds with ratings as low as BBB-, which is on the cusp of the investment-grade/junk threshold (one notch below BBB- is the start of the junk BB+ band). Previously the RBA had prudently required any corporate bond against which it offered liquidity to have a minimum AAA rating.

One gets the sense the RBA was pressured to do something to alleviate the extreme illiquidity in the investment-grade corporate bond market, which has frozen many portfolios that were assumed to be liquid. Investors had chased yield in questionable securities with ostensibly solid investment-grade ratings, but which were clearly going to be a liquidity problem in any serious shock.

The absence of trading in these investment-grade corporate bonds has also meant that many valuations were at artificially inflated levels during the March crisis given the true bid, or real price, had not been properly disclosed. We are seeing similar issues with illiquid commercial property valuations right now, which are only slowly being written down.

The RBA was evidently resistant to the idea of emulating what its peers in the US and Europe have done by buying corporate bonds outright and assuming their non-trivial credit risk on its balance sheet. I concur with governor Phil Lowe’s commendable conservatism in this regard.

Instead, it will extend its repurchase (or repo) arrangements to allow owners of corporate bonds to go to the RBA and get short-term funding against them with a minimum margin that is supposed to protect the RBA against any losses on these holdings. For example, in the case of a five-year BBB-rated corporate bond, the RBA requires a 22 per cent margin to insure itself against the bond blowing up.

The consensus among traders is that while this policy change will help a little, it is not going to revolutionise liquidity in corporate bonds nor precipitate a sudden normalisation in spreads.

In contrast to bank-issued bonds, the credit spreads on corporate bonds in January 2020 had compressed to levels that were even lower than their historic nadir in 2007 prior to the GFC (bank spreads were between 2.5 times and 8.5 times wider than their 2007 marks). And yet whereas banks had radically deleveraged their balance sheets since the GFC, corporates had been issuing bonds to buy back their equity and boost leverage to new highs.

Australia’s largest market-maker in corporate bonds advised clients that the RBA’s decision would have minimal impact on spreads compared with the alternative of outright central bank purchases.

They think that the cheap RBA funding now available for buying corporate bonds will help market-makers facilitate transactions, although this money needs to be repaid at some point.

Their conclusion was that “in our view the primary driver of the poor liquidity and the recent extreme spread widening is the inherent credit and solvency risk of corporates".

“If investors are able to access repo on corporates, then it may alleviate some forced selling in times of stress, but that is, in our opinion, minimal,” they continued. “Cheaper funding of bonds in a financial crisis doesn’t take away fundamental concerns of credit worthiness.

“From the perspective of a market-making desk, we can say with confidence that the thoughts of where we could fund our corporate bond holdings was not a factor of note when bidding in March and April. Foremost was credit worthiness.”

2 topics