Hofflin: Why returns will remain volatile (and energy and value will outperform)

Famed British economist John Maynard Keynes once said, "When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, Sir?"

The same thinking can be applied to markets. The facts have changed, and so too should investors' portfolios.

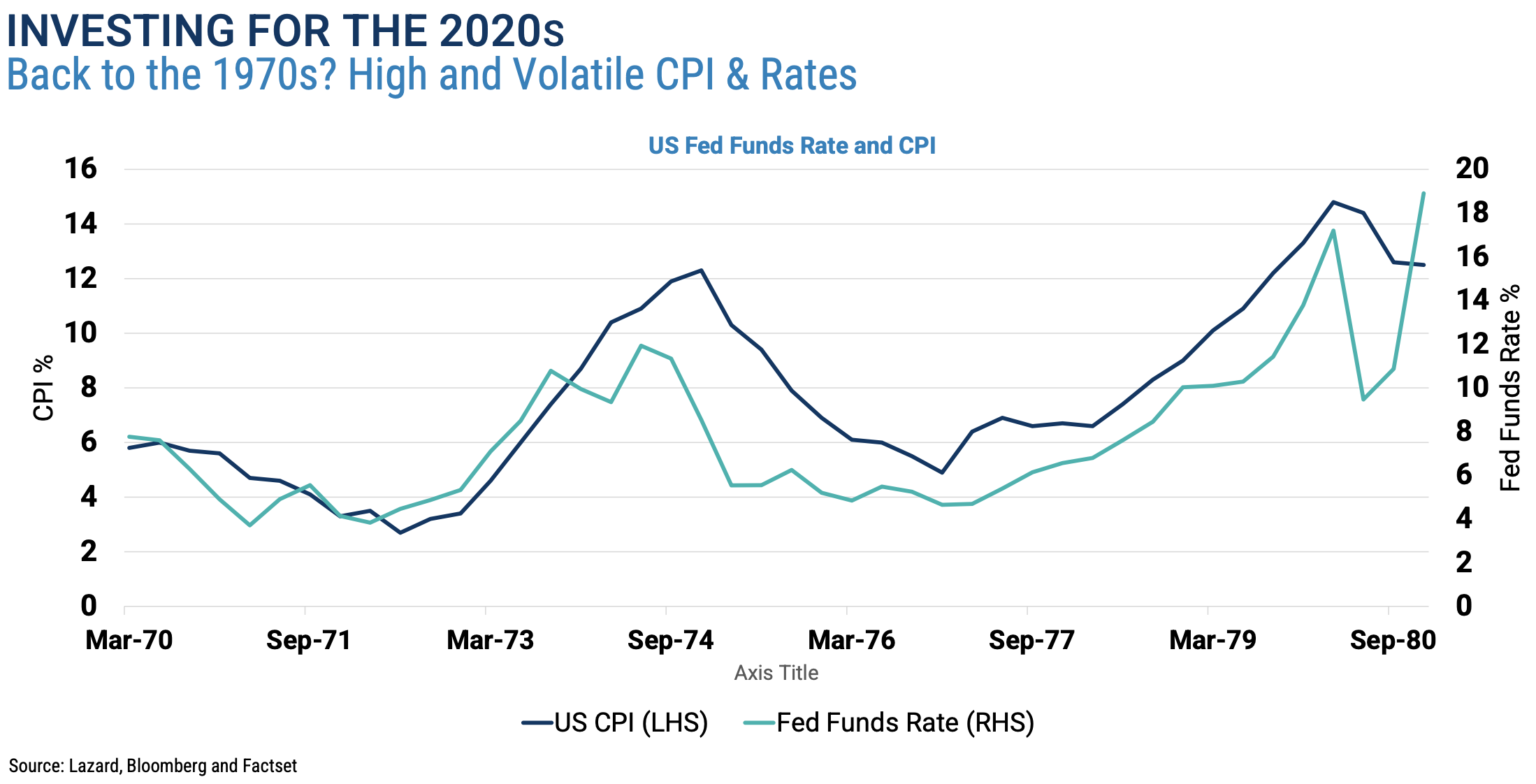

The facts, while different, do match up pretty well with those of the 1970s, prompting many commentators to draw parallels between the two timeframes. A tight energy sector, high inflation, low wage growth and supply shocks following accommodative monetary policy are all features of both today’s market and markets in the 70s.

Drawing parallels, however, is of little use if you can’t also draw lessons from them.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Dr Philipp Hofflin, portfolio manager on the Australian Equity Team with Lazard Asset Management. Here, he provides a sage framework for value investing that cuts through the noise, narratives and cognitive biases that will undoubtedly lead many investors astray right now.

.png)

Back to the 70s

Investors shouldn’t automatically assume that talk of Fed “pivots” and terminal rates of 500-525 basis points in 2023 will bookend this period of pain, thereby precipitating a return to business as usual.

Inflation did fall significantly following the recession of 1974 that the Fed caused through its tightening, but taming inflation didn’t change the market overnight.

“The second thing, of course, was that despite the fact there was a deep recession, inflation wasn't really vanquished. It kept on going," Hofflin says.

It’s also worth mentioning that the Fed rolled out the big guns in the 70s. Much bigger guns than it’s firing today.

“I think one of the most dramatic differences is that in September 1973, when the US inflation rate was 7%, the Fed Funds rate was over 10%,” says Hofflin.

“In January 2021, when inflation was at 7% in the US - before Ukraine - the Fed funds rate was 10 basis points and they were doing quantitative easing. They’re clearly much more behind the curve this time.”

The 2010s were a one-off gift

The 2010s were an aberration, the hangover from which will likely be felt for years to come, Hofflin says.

Back then, debt cost virtually nothing, central banks pumped markets full of liquidity via quantitative easing, and fiscal deficits went berserk.

“Don't base your thinking on the 2010s because they were very unusual and in particular do not base your thinking on 2020 and 2021 in terms of the stock market because that was a bubble,” says Hofflin.

"There are people out there who are saying, 'these multiples are falling, these stocks are getting cheaper and cheaper, things will go back to where they were before.'

"We are saying, 'Well, I think that's probably wrong. You're probably going to be disappointed'."

Moreover, the correction back to normal, whatever that looks like, still has a long way to go.

“The adjustment on prices has only just begun, particularly when it comes to value stocks around the world and in Australia," Hofflin says.

Ultimately, returns will be lower because multiples won’t be artificially pumped as they have been.

“It'll be cyclical instead of just set and forget. Energy prices might be high. Inflation might be troubling, and some rates will be higher. It will be a very different environment, and definitely a harder environment," he says.

Don't bet on safety nets

In recent years, when growth has slumped or we've been hit with a pandemic, the Fed has come swooping in like Don Quixote on horseback. But investors shouldn't expect the same central bank exuberance now.

"I think most people would agree eventually something somewhere will break," Hofflin says.

"There are some people who are the school of the pivot who say, 'Well, something was going to break and when it breaks, the Fed will come in and say don't worry, I'll fix it and it's fine, we'll pivot'."

This creates a level of moral hazard central banks will be keen to avoid. If and when something breaks, they will do their jobs, but don't expect golden tickets.

Hofflin points to the recent UK gilt crisis as an example. The UK government shocked the world by announcing historically large tax cuts in the middle of an inflation crisis. That sent bond yields skyrocketing, and UK pension funds were left facing margin calls that threatened to wipe them out.

The Bank of England stepped in and re-instigated quantitative easing to artificially stabilise the bond market and save the pension funds.

"The Bank of England said, 'We're going to give you two weeks to fix this. We're going to use our balance sheets and fix prices. After that, they raised interest rates by 75 basis points," Hofflin explains.

He believes this will be the kind of approach taken by the Fed in future crises.

"It's much more likely the Fed will come in and say, 'Yep, I'm going to fix the problem here because I don't want that to break. I'm going to use my balance sheet to support you there, but after that, I'm going to keep things tight.' They're looking at a bigger picture now," Hofflin said.

New age, new positioning

Investing for the 2020s will all be about tempered expectations. It will be a game of inches, not yards.

"The market was willing to give growth stories the benefit of the doubt," says Hofflin, who reckons markets will now be far less forgiving.

"You've seen what's happened to all the growth stocks already."

So what does this all mean from an asset allocation perspective?

Lazard expects inflation to be higher and more volatile, rates to be higher than the 2010s, and earnings to be more cyclical. In equity markets, expect returns to be cyclical and more volatile, dividends to be a large part of total return, energy outperformance, and value to outperform growth.

"You're better off investing in companies with low multiples, high yields and low expectations. There's still far too many stocks out there that are on 25, 30, 35, 40 times. I'd be very cautious about those," Hofflin says.

He likes QBE Insurance Group (ASX: QBE), a company on eight times FY22 earnings and exposed to the premium rate cycle.

On energy, Lazard remains overweight on a structural view that's independent from the cyclical classification the sector is normally given. Woodside (ASX: WDS) and Santos (ASX: STO) are top 5 holdings in the Lazard Select Australian Equity Fund.

The bullishness on energy is largely based on the lack of investment on both sides of the transition; so, in both legacy energy as well as renewables. In short, the supply curve has shifted to the left.

"China's doing a pretty good job, but the rest of the world I don't think is, and the simple fact is that we have made the decision to dramatically lower investment in the old fossil fuel energy sources, which are 80% of the world supply," Hofflin says.

"On the other side, we're not doing enough on the renewables to cover that gap."

As Hofflin points out, roughly 75% reinvestment in fossil fuels is required every year just to replace the natural depletion of fossil fuels.

Finally, Hofflin is bullish on Computershare (ASX: CPU), with its positive exposure to rising rates.

4 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned

1 contributor mentioned